Whether buzzing stridently outside your tent, or feasting contentedly on your flesh, a mosquito’s auditory system will “not pick up frequencies in the same way as our human ears do”. Their feathered antennae, as we learn from a fascinating investigation into “non-human listening” by Norwegian composer Espen Sommer-Eide, “reach out and touch the sounds.”

“The male can hear sounds in the range of 30–2000 hertz,” Sommer-Eide continues, “specialised for listening to the flight tone of female mosquitoes. It listens for the sound of her wings buzzing at around 400 hertz, and starts adjusting its own tone, in what may be called a tuning duet.”

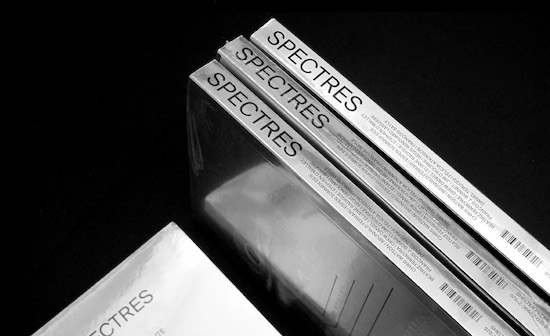

This kind of reflexive back-and-forth between audition and composition, between the receptive act of listening and the creative act of music-making, is at the core of the project implied by this slender, silver-bound volume from the Groupe de Recherches Musicales of the National Audiovisual Institute (Ina-GRM). “Composing Listening” reads the book’s polysemous subtitle, one possible reading anchored by a page in the front matter taking the form of a kind of manifesto – or Fluxus-like event score: “LISTEN – RECORD – COMPOSE – DEPLOY – FEEL”

The thirteen essays that follow lay their emphasis pretty firmly on the first item of this warmly peremptory agenda, exploring – and enjoining to action – the auditory sense within a diverse array of contexts and perspectives. So we find Chris Watson recalling the change of perspective prompted by his first tape recorder, aged 13: “I started to listen,” he says simply. And by “tuning in to the sounds of everyday life” he discovers new life, new strangeness and new intensity in the once-familiar soundworld of his Sheffield youth. We have composer Brunhild Ferrari, widow to GRM co-founder Luc, recalling the long “exploratory” walks she and her husband once took, seeking out “silence, a sound, or an audible event”, like the pebbles tossed on the beach at Étretat with friends whose captured sounds ended up in the mix of Luc Ferrari’s early concrète masterpiece, Hétérozygote (1963–64). And we hear from Drew Daniels, of Matmos and the Soft Pink Truth, finding analogies for the work of electroacoustic composition in the attention he pays to the screaming, splashing, and gurgling of a hotel shower cubicle.

It is over sixty years since the foundation of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales in Paris, but its roots stretch back even further, to the wartime experiments of broadcaster Pierre Schaeffer with microphones and shellac discs at the Resistance cell-cum-experimental studio of the Club d’Essai. As he records in the pages of his 1952 book, In Search of a Concrete Music, Schaeffer had set out in search of “the most general musical instrument possible.” In the end, what he found was something more like a new language, a new solfège, a new form of relationship with the sounding environment. Arguably, in his tethering of aural attention to an analysis that would lead directly to the creation of the new, Schaeffer did for the ear what Francis Bacon’s Novum Organon had done for the eye, more than 300 years earlier.

When, in a 1957 article for the Revue musicale, Schaeffer sardonically ventriloquised the complaints of his detractors – that the use of electronic sounds, prepared instruments, tape effects, sound spatialisation, and so forth were all a priori of “no musical interest” – it was clearly the last enumerated complaint (“Finally…”) that the author found most egregious: the notion that “the musical work exists in itself, as unheard, and the auditor must be considered as a non-participant in the genesis of the work”. As the editors of the present volume (publisher/designer Bartolomé Sanson, and the current artistic director of the Ina-GRM, François Bonnet, otherwise known by the recording alias Kassel Jaeger) make clear in a ‘Foreword’ which quotes Schaeffer’s list in full, “it was already intellectually impossible to act as if nothing had happened”. The advent of recording technology, and the response to that innovation on the part of composers and music theorists, had dragged that genie out of the bottle, smashing to pieces the brittle work concept inherited from the nineteenth century. Never again could one tenably deny the complicity of the listener in the act of musical creation.

Two older texts by an older generation of musique concrète pioneers, Schaeffer’s grouching in the ‘Foreword’ and François Bayle’s reflections on the creation of the GRM’s loudspeaker orchestra – the Acousmonium – at the end, act as bookends to a selection of new writing by some of the most active participants in contemporary electroacoustic music. Jim O’Rourke offers a portrait of the young artist as fan, recalling his youthful drooling over Frank Zappa records and images of Léo Kupper’s GAME machine. Stephen O’Malley narrates the to-and-fro of action and attention in a live performance of a work by Alvin Lucier. Félicia Atkinson traces out a kind of perspectival listening, an audition that works through “different depths and dimensions,” through “zones of perdition” in a trembling sonic voyage that leaves the subject “unstuck from things.”

Spectres is intended to be the first in a new annual series from Shelter Press. This is to be welcomed. The contributions to this first volume are never short of illuminating, frequently offering new and heretofore unimagined possibilities for the exploration and re-assembly of the sonorous universe. From its exquisitely designed sleeve to its expertly curated contents, Spectres is nothing less than an essential guidebook to better listening.

Spectres, edited by François Bonnet and Bartolomé Sanson, is available now from Shelter Press