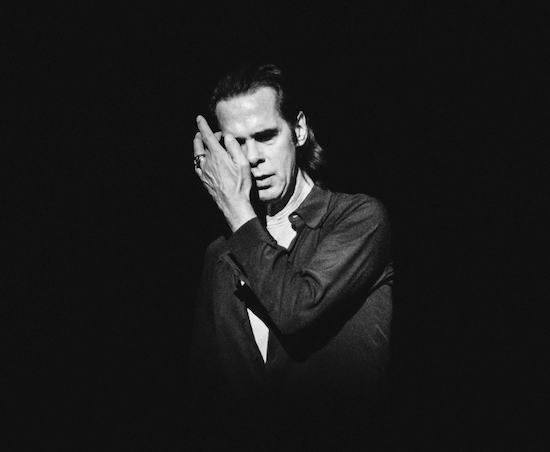

Live photograph by David Barajas

For a period in the early 1980s, Nick Cave’s The Birthday Party held a reputation as being the most violent band in Britain. Aside from their potent musical assault of cacophonic rage which sounded like thunder and electricity all rolled into one vociferous torrent, the band’s relationship with their audience was a fraught and often physical one.

When the band arrived in England in 1980, they landed with a thud of disappointment. The world they read about in NME back home in Australia failed hopelessly to live up to their expectations and they found themselves at the centre of a musical scene they largely loathed (with the exception of allies such as The Fall and The Pop Group). Combined with the arrogance and fury of youth, this saw a level of contempt brew and manifest from Cave and co. towards their new audience. At a 1982 performance, a growingly restless crowd broke out into fights amongst themselves as the band waited to go on. As a flustered promoter rushed backstage to inform them of the escalating tension, Cave replied: "Good. I hope the pigs kill one another."

By this stage people were actively attending shows to cause trouble and they would often get back what they gave. One performance was interrupted by a fan that got on stage to urinate on bass player Tracy Pew whilst he was playing, only for Pew to hammer his bass into the head of the offending pisser and send a stream of blood oozing down his face. Punches and kicks were often exchanged between band and audience and one fan called Bingo – who had taken offence to comments Cave made in the press about English audiences being stupid sheep – decided to make it his mission to torment the band. This came to a head one evening when Bingo decided he would breathe fire at the band whilst they were performing, bringing with him his own bottle of meths and spewing a DIY fireball in an attempt to engulf the band. Such maniacal behaviour led the band to hire Bingo as their minder – as someone ready to pounce on stage and brandish a metal pipe at any audience members crossing the line as he once had.

By 1983 in one of Cave’s last major interviews before The Birthday Party broke up he told NME: "I don’t know of another group who are playing music that is attempting in some way to be innovative that draws a more moronic audience than The Birthday Party. There’s always ten rows of the most cretinous sector of the community."

Fast forward to 2019 and Nick Cave is in the middle of a worldwide In Conversation tour. An environment in which he is actively encouraging participation and engagement with his audience. It’s the culmination of a period of several years in which Cave’s relationship with his own audience has gone under a profound transformation. “I feel like I can plug deep into the soul of my audience,” he says on stage as he introduces the evening in Manchester.

Anyone who saw the Bad Seeds touring Skeleton Tree would have seen a shift take place from previous tours, with Cave spending chunks of the show amongst the front row interlocked with the audience’s reaching and clasping hands. The gigs would all then finish with a mass audience invite on stage as the band played ‘Push The Sky Away’, surrounded by scores of people all sat around the band like an extended family.

Then came the Red Hand Files which Cave launched last year, a website that further explored this audience interaction. It’s a forum that allows people to submit questions directly to him – he gets about 100 a day he says – and he sends out responses like a newsletter. It’s become something that has changed in tone quite a lot, shifting from more simplistic questions to deeply personal letters from fans that touch on heartbreak, loss, grief and pain. Often it seems people are looking for something in the way of comfort and solace from him as much as they are definitive answers.

A large part of this is because Cave himself underwent life-altering trauma. After the death of his 15 year-old son Arthur in 2015, Cave was a changed man. In the 2016 documentary One More Time With Feeling, he speaks about how this change altered his relationship to both himself and the public. “Most of us don’t want to change. What we do want is sort of modifications on the original model. We keep on being ourselves, but hopefully better versions of ourselves. But what happens when an event occurs that is so catastrophic that we just change from one day to the next?” He goes on to give examples of how this related to his interactions with the public, speaking of crying into the arms of strangers in the street and feeling someone grab his arm in the bakery to say, “We are all with you, man,” and for him to turn around “and all the bakery is looking at you with kind eyes.”

Cave speaks about this on stage and how an act of unjust cruelness from the world changed his perception of it. “When I realised that the universe didn’t care about me or the people in my life, that led to me caring more about the universe and the people in it.” And the people in it clearly care about Cave too; there’s countless people who have flown in from other countries for the event and many shake and cry their way through questions as they share their own traumatic stories – often citing Cave and his music as a vital lifeline.

Live photo by Daniel Boud

However, thankfully, the evening doesn’t descend into a kneeling down at the altar of Cave event. For every unnecessary or sycophantic statement about how brilliant Cave is from one audience member, there’s a biting response to another. Although Cave doesn’t prevaricate and answers fully and honestly where possible, it’s his humour that carries this format and stops it entering into over earnestness or public therapy. If one question is particularly long and emotionally gruelling then Cave will plonk down for a couple of songs at the piano to break it up or he’ll answer a question with a song, performing his favourite song he’s written ‘Brompton Oratory’ or his favourite song someone else has written, such as ‘Cosmic Dancer’ by T-Rex.

He’s also still brusque and spiky enough to keep boundaries and not over indulge. When one young photographer asks if she can take portrait photographs of him, it’s a flat “no” before he’s already looking for the next arm up in the audience. When one woman describes Cave as her second favourite songwriter to Bob Dylan, he says, “I’ll let it pass. As long as it’s not Morrissey.” Another person rambles incoherently about their dreams and how Cave features in them and Cave cuts her off and simply says, “I’m sorry, I don’t have a fucking clue what you’re talking about” and sits down for a debut performance of ‘Breathless’, which he plays for her instead. When another woman asks which of his songs her 11 year-old child should learn on piano, he tells her sardonically ‘No Pussy Blues’.

But the intention behind these events is clear: Cave is trying to forge a meaningful exchange with his audience. There’s a palpable feeling that he owes them something; so overwhelmed by the kindness that was expressed to him at his darkest moment he seems to be offering something in return to other people who may be in theirs. Whilst the hefty ticket prices mean only a select number of Cave’s audience are going to have the opportunity for this to take place in person, it seems like a sincere attempt to strengthen a bond that is typically one-sided.

It’s also an approach that stands in stark contrast to the pernicious growth of things such as spiralling VIP packages and meet and greets, in which fans are charged exorbitant amounts to briefly meet artists and have an a production line photo taken with them. It also feels like an attempt to remove oneself from the narrative social media can create – one stripped of context and nuance and reduced to spicy headlines and alluring grab quotes. Cave seems to be shooting for something deeper here. “It’s become a huge part of my daily life,” he says of reading through the stacks of daily Red Hand Files letters. “It’s been transformative.”

All talk this is not, however. Cave spends three hours on stage and performs 19 songs. Alone at the piano the bare essence of some songs feel suitably paired with the often-raw nature of the evening’s conversations. Usual piano-led offerings are here – ‘Into My Arms’, ‘Love Letter’, ‘Ship Song’, ‘God Is In The House’ – but it’s the tracks that most characteristically don’t lend themselves to solo performance that often prove to be the biggest revelations. Grinderman’s ‘Palaces Of Montezuma’ bounces along feeling as tender as it does joyous, ‘Papa Won’t Leave You Henry’ is stripped of its defining rhythm guitar propulsion yet Cave’s piercing stabs of the piano drive it forward with a wonky venom, whilst ‘Jubilee Street’ and ‘Stagger Lee’ both still manage to feel ever-charging, growing and transcendent even when stripped of the Bad Seeds’ incendiary accompaniment.

At one point Cave tells the audience that this format – with him vulnerable and exposed to the whims of the audience’s unpredictable questions – has “brought the terror back” to performing. Only this time around the artist-audience relationship has strengthened to the point that nobody is trying to set Cave on fire; no one is storming the stage to piss on a musician and no one’s leaving with a bloody head.

Conversations With Nick Cave continues in the UK, Australia, Scandinavia and America