“Vanity! Vanity!”

Sixth months after Prince’s accidental overdose, a singer in a raspberry red beret and frock coat – a satellite of Prince’s orbit, who’d recorded at Paisley Park – grabbed me as his Official Tribute in Minneapolis was climaxing. I was battling to leave before the lurching assemblage of stars and local talent could gore ‘Purple Rain’.

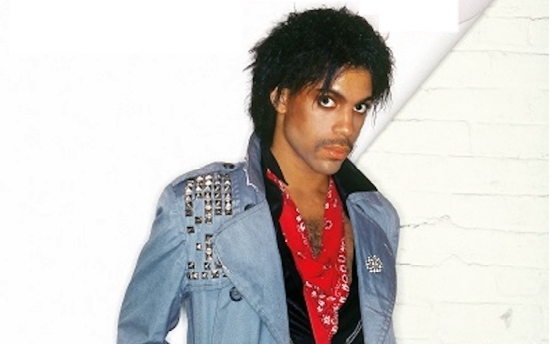

“Sorry,” she said, “you look like Vanity… you know who she was, right?” I knew, alright.

I’d dressed like her, deliberately, in white veil and corset. Prince had recently dedicated ‘Little Red Corvette’ to the actor-singer born Denise Mathews during his ‘Piano & A Microphone’ tour. “Someone very dear to us has passed…” But what was the point, flying 3,854 miles to play homage as Vanity, when Prince wasn’t here? I couldn’t speak for the tears in my throat and she flinched.

Later that night, I apologised to the frock-coated vocalist when I found her again at First Avenue nightclub. We danced underneath The Time performing ‘Jungle Love’.

Copies of Vanity smatter the new Originals album. This turbulent, funky, robotic carousel of unreleased recordings coheres around Prince’s idea of the “headstrong… finest woman in the world”, a lingerie-clad harpy he named Vanity. Bar the bonobo funk of ‘Jungle Love’, the best tracks were written for women or made famous by them, including ‘Manic Monday’ and ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’. Prince sings the female part – and Prince in a camisole cranks the machismo, too. His snare smacks. His cymbals crash. Feminine falsetto and contralto spark against submerged rock guitar, stag-leaping saxophones and punch-drunk, stinky basslines.

The album is dominated by the automated fleshy fantasy of Prince’s 80s synth innovations and his Frankensteinian transfusions of the Linn M1 drum machine. Individually tuning the outputs at the back, he spawned womb-like, narcotic, trashy voices. The LM-1’s presence – and absence – in Originals, piques Prince’s feminine longing for a love that rarely arrives.

Who Vanity was, or might have been, doesn’t matter. Prince’s myriad dating history is embedded in this album’s jumpy pelvic floor. Sheila E was engaged to Prince. So was Susannah Melvoin, who co-wrote ‘Starfish & Coffee’ and sings on ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’. Jill Jones, about whom Prince wrote ‘She’s Always In My Hair’, ghosts, too, singing into Prince’s microphone on ‘The Glamorous Life’. In these songs and others, Prince circles one Vanity-style nymph. She is Lolita and Darling Nikki. She is The Beautiful One who “makes me so confused.” She is also – naturally – Prince.

Prince named Denise Mathews ‘Vanity’ for her resemblance to him, a female double who enabled Prince’s “nasty love game”. Here, ‘Sex Shooter’, ‘Make-Up’, ‘The Glamorous Life’, and ‘Holly Rock’ describe Prince’s nymph: flippant, financially independent and promiscuous. She’s a post-feminist, who prefers mink coats to “a man’s touch” – except when, as in Sheila E’s ‘Holly Rock’, she demands his “big stick” for satisfaction. Despite her “coy little wink”, she’s scared of “real love”, as torn as Prince between provocation and craven seduction of the opposite sex. “If I wear a dress/He will never call/So I’ll wear much less/I guess I’ll wear my camisole,” Prince raps, playing Vanity as a robotic boudoir vamp in ‘Make-Up’, a proto-acid throbber that might see Prince ruling techno clubs again in 2019.

Originals lifts off with an electro pop ditty hissing for female ejaculation, ‘Sex Shooter’, written for Vanity 6. Propeller blades whir as Prince skips into the role of a sex “bomb… ready to explode/I’ll be your slave, do anything I’m told.” Between effluvial keyboard squirts and hydraulic drums s/he begs the man to pull “my trigger”. A prancing, clavinet-style melody garters those synth frills with a tough elastic layer. The steadily stepped, buzzing bassline amasses dark matter. And so a male jerk-off song becomes a girly sizzler, as the Vanity figure crows, or croaks, “No girl’s body can compete with mine/No girl’s rhymes can top my lines.” While the man’s cunnilingual kisses are demanded, his status is slippery: “be my plaything, main thing, pillar of stone.” This nymph’s chosen one is anyone.

Therein lies Prince’s anxiety. Vanity left Prince before filming began on Purple Rain and was replaced by Apollonia. The Vanity-type leaves. Possibly, as Vanity once said in an interview, she is “looking for a Master”. In this, as in her paradoxical desires, she echoes Prince, seeking a Higher Authority to break him down, like the selfish king of “the land of sin-a-plenty” who rejects his nymph (this time named Electra) in ‘The Ladder’. Prince’s sadistic imaginings of Vanity are documented in his notebooks for the film of Purple Rain, now in the Paisley Park archives. In one fight, he envisions, “a valiant effort by our hero to deface her… but that’s their relationship.”

Sometimes, it helps to imagine the girl-next-door, a girl who has to go to work on Mondays. ‘Manic Monday’ opens with Prince sympathetically voicing a mid-western gal with bed-tousled hair. Last night’s ill-timed sex hangs over a ditzy piano, reverbed into weird country rock, with Fleetwood Mac harmonies. Prince maintains cascades of acoustic guitar and rolling drums throughout the eerie half-tones of the middle eight. Unfortunately, as in his film, Under The Cherry Moon, Prince enjoys his ordinary-girl act so much he turns campy. Describing poverty-threatened shagging (“have to feed the both of us/Employment’s down”), his slapstick “ooh-ooh-ooh-ooh”s leave the wheels of this stagecoach spinning.

Still, there is nothing more mesmerising than not getting what we want. One of the album’s surprising gifts nestles in what’s missing, as in ‘Noon Rendezvous’. Our ear gulps absence, when, in this panty-dandling ballad for drummer Sheila E, her instrument is reduced into a gigantic flexed shudder. Prince’s sore-throated falsetto, singing a cappella against that ghostly drum, is intimate, yet distant. His piano richly embraces his vocal melody, as shyly yet oh-so-slyly, s/he invites sexual instruction from her man – “new tricks.” Singing in a lonely crater, this girl sounds deep yet vaporous, intoxicated by her isolated imaginings. Sex is better on the moon.

‘Holly Rock’, an exotic circus of a jam written for Sheila E’s hoped-for breakthrough into Hollywood, casts Prince’s feminine double as both wicked circus MC and an angel whose neon voice promises fame above a male chorus chanting in a sacrificial ring: “Rock, rock, Holly Rock / Everybody wants Holly Rock!” Triple-vaulting sax, Latin percussion, jazz drums, and techno bass monkey round our rapping ringmistress: “Sheila E’s my name … funkier than a wicked witch/I’ll pet ur kitty, ur little dog 2/Don’t U wanna b my bitch?” Prince revels in her supremacy and, indeed, her vulva (“my toy box”), adding in a stage whisper, “Now try to dance to that!” Prince loved a female rap.

Prince and his überwoman galvanise each other. In ‘Dear Michaelangelo’, a glittering, difficult song bevelled with biblical and cinematic references, a muse chases her artist. The misspelling might be an error, or Prince’s Christian unconscious, hinting at the true identity of the Great Artist. A bruised few months after he died, I smiled with a trembling lip, coming across The Oxford Dictionary of Rhyme whilst going through the books in Prince’s study in Paisley Park: O my beautiful nerd! Prince’s pedantry blends here with mystical yearning. An artist, ‘Michaelangelo’ is adored by a Florentine “peasant of female persuasion” (the poor, being closer to God, get a divine pass for gender reassignment, plus some handy rhyming syllables). She trails palpitations of bongo, conga, and percussion over Michaelangelo’s garden, keening to him, “to save her from death’s invitation”. His art is sex; sex is art: “I look at your paintings/And I’m with you in your bed.” Prince’s peasant is his nymph in disguise, fearing that ‘A Glamorous Life’, without love, is a living suicide. Her prayers are shackled to the free-jazzing alto sax, voicing the theme of another fictional, pious floozy, Lara in Dr Zhivago. Here, ‘Michaelangelo’ is the Italian Church artist. He is St Michael, guardian of Eternal Life. Embodied by macabre guitar, crackling thunderstorms before catching fire in a tortured solo, he is also Prince himself, flickering his zoetrope of dissonance and half-rhyme:

“No one could speak of passion and touch her

Touch her the way that he does

It was him (life without love) or a life without love.”

When Prince’s power and vulnerability collide, as they did during the whirling summer of 1984, he collapses before this “life without love”. The priestlike hymn, ‘Love Thy Will Be Done’ and the heart-bursting elegy, ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’ are Prince’s ripostes, in Originals, to the nymph within himself. At the time of this version of ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’, his post-Purple Rain fame is escalating, his trusted PA, Sandy, leaves and Prince’s relationships with Sheila E and Susannah Melvoin are getting complicated. The meaningless funfair of life revolves around an exquisitely fragile vocal. A Beatles-like mellotron-effect drips “lonely tears falling”, round and round. Prince’s girl sounds awfully like himself, the pronoun‘U’ slipping into ‘me’ (“I know that living with me baby is some kind of hard”). Taking himself to task, his mellotron sorry-go-round is smashed by Prince’s heavy guitar. His grieving vocal is sledgehammered by a church chorus more severe Gregorian monk than reassuring gospel. The male sax expresses what Prince can never say, while Prince’s guitar snarls down off-key digressions. Susannah Melvoin’s gauzy harmonies climb tenderly upwards. His final, multi-tracked plummet is operatic grandeur on a swizzle stick. It shouldn’t work – but does. The punishment fits the crime.

Prince wanted to be understood yet struggled to understand love. His fear of intimacy, fused to his emotionally closed nymph, radiates musical tension. In 2014, the spooky, tumble-down vocals of ‘This Could Be Us’ and its ghostly artwork, recalling Apollonia replacing Vanity on that Purple Rain motorbike, confessed Prince’s continuing “confusion” – a word he used joyfully, too. For, as ‘Originals’ shows, Prince’s never-ending nasty love game is artistically fertile. In 2015’s moonlit, electro-soul ballad ‘June’, his estranged wife (“everyone’s dream”) leaves a lonely musician on his birthday. This marriage, “way too hard”, compresses new liquid exhalations in Prince’s drums and keyboard. ‘June’ is hypodermic, haunting, brilliant. The psychedelic bluesy chanson, ‘When She Comes’ is more optimistic, as Prince himself could be around his last, secret girlfriend and talented collaborator Judith Hill. Here, Prince submits to his freewheeling, “sweet bird of prey”. He nurtures her orgasms in French-stockinged flights of ironic accordion. “It’s always a shock, when she undoes the lock” of Prince’s cage – but they swing together in trusting, balletic pastiche.

Writing under aliases Christopher, Joey Coco, Alexander Nevermind, and Jamie Starr, Prince is freed in Originals to experiment with genres and with doppelgängers more lewd and abject than the commercial star known as ‘Prince’, even indulging – regrettably – in the schmaltzy ‘You’re My Love’ for Kenny Rogers.

There are scores, possibly hundreds, more ‘originals’. But, as Nona Gaye, Marvin’s daughter and another Prince girlfriend-collaborator, agreed, as we consoled each other outside Paisley Park one night, there is nothing more original than that vice Prince shares with his nymph. “There was that pull: ‘love me, love me’ – he wanted to know if you loved him – and you’d say, ‘I do, I do’. Then he’d run away again.” Prince and his dream of Vanity cannibalise your heart before absconding.