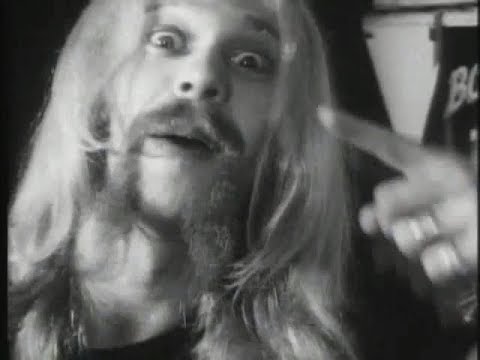

Venom

Earlier this year, I was in a backstreet bar in Bangalore with Nolan Lewis and Ganesh Krishnaswamy of Kryptos, as they bemoaned the state of Indian metal. "If you look at Indian bands right now, there’s no melody. It’s all aggression," Lewis said. "How heavy can we be? How many breakdowns can we fit in this song? How hard can I scream my lungs out? And in my opinion there’s no substance to it."

"We just like the melodious aspect of two guitars playing those harmonies," Krishnaswamy said. "There’s always melody. We like metal more than aggression."

The sound they loved, they said, was one that’s 40 years old. One that took metal into the pop charts. One that helped shore up the careers of an earlier generation of hard rock artists, who rode its success back into the charts. One that transformed metal in the UK, and sowed the seeds for thrash (and therefore, paradoxically, for the extreme metal styles that eschewed melody). The sound they loved was that of the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal.

NWOBHM was, in some respects, a media invention. The phrase itself was coined by Sounds editor Alan Lewis, inserted as a sub-heading on Geoff Barton’s review of the Heavy Metal Crusade gig – featuring Samson, Iron Maiden and Angel Witch – at the Music Machine in London (now Koko) on 8 May 1979. It came to be applied to scores of bands, regardless of what they had in common, so long as they sounded at least faintly metallic.

Not every band embraced it. At the commercial end of hard rock, Def Leppard continue to insist they were never a NWOBHM band. "When we started getting a bit of traction we noticed we were being lumped in with all these other bands we weren’t aware of," Leppard singer Joe Elliott says. "And the first thing we did was react against it. We went: ‘We don’t want to be part of a movement.’ Same as you can’t accuse the Beatles of being part of the Mersey sound. That was always our stance and we’ve stuck with it for 40 years."

At the other end of the sonic spectrum, Cronos from Venom is just as adamant. "What made me put my foot down was when Michael Jackson got in the bloody heavy metal charts in Kerrang! with Eddie Van Halen doing a solo on ‘Beat It’. No 1 in the heavy metal charts? Michael Jackson? I saw red. I just couldn’t believe it. So we were doing an interview with Garry Bushell for Sounds. And when he said, ‘So about this heavy metal …’ I was like, ‘WE ARE FUCKING NOT HEAVY FUCKING METAL!’"

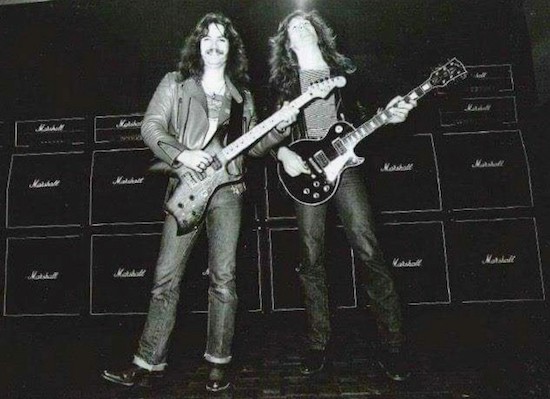

Iron Maiden

NWOBHM had its roots in a confluence of circumstances. By the second half of the 70s, British hard rock was in a peculiar state. The titans of British hard rock were not in a great way, either splitting (Deep Purple), directionless (Black Sabbath), or lumbering into druggy ennui (Led Zeppelin). The songs were long, the solos endless. There were exceptions, though: Judas Priest were moving away from the dreary blues rock of their debut towards something diamond hard and razor sharp; Thin Lizzy and UFO were perfecting a melodic, concise hard rock based on songs with gigantic hooks and radio-friendly tunes. These were the bands who were providing something exciting to younger fans of hard rock.

While Lizzy and UFO and Priest were consolidating, though, hard rock in general was being sidelined. Not just punk, but disco had taken their toll on the grassroots circuit for rock bands. "So many punk bands got live music banned from the little clubs around the UK, at the same time as disco was really kicking off," Joe Elliott says. "The people who ran these clubs found the easy way out in getting a DJ in."

"If you were in a band you had a hard time getting a gig," says Neal Kay, who DJed at the Bandwagon pub in Kingsbury in north west London. "Walk in the door with long hair and that was an end to it. Basically, it was very tough for bands."

But by the end of the 70s those attitudes were softening, and a grassroots circuit was opening again, to a generation of bands inspired as much by the directness and DIY spirit of punk – cited as an influence by scores of NWOBHM musicians, though always denied by Iron Maiden’s Steve Harris – as by the melodic hard rock bands. And they sprang up organically, all over the country, unaware of each other at first – in the North East, in South Yorkshire, in Birmingham, in London, which was one reason why NWOBHM proved to be so varied, so free of stifling uniformity.

Kay was one of the key people in creating a climate in which young heavy bands could thrive, and thus a scene for Barton to report on. A former club DJ who had become disenchanted with music and moved into truck driving, he had been taken by a friend to the Bandwagon one Wednesday night in 1975 by a friend. "I was enjoying the sounds, then to my astonishment one of the guys on stage said, ‘We need a rock DJ here. If there’s anyone who would like to try out, come up now.’ I took them up on it and got the job."

At first Kay did one rock night a week, but then, he says, a police raid in 1977 put the club under threat. In court, Kay testified that there had never been any trouble on the rock night, with its older crowd, and the magistrate ruled that the Bandwagon could stay open so long as it played only rock music. Kay took over, installing a massive JBL/Martin soundsystem to play the music he loved as loud as possible. "It was sensational. It was massive. It was so loud we had to fly the console from the rafters on chains to stop the acoustic vibration on feedback. I knew that if we were going to make anything of it I had to get the media involved. I started pestering Sounds, talking to Geoff Barton and telling him what we had. Once he came here it changed everything: he wrote a piece called ‘A Survivor’s Report From A Heavy Metal Disco’. He did a double-page spread in Sounds. We changed the name and it became the Bandwagon Heavy Metal Soundhouse. The word ‘disco’ wasn’t strong enough to describe what we were doing. We were delivering a concert, but in vinyl."

Outside London, scores of young musicians were getting the itch to play the music Kay wanted to deliver. Up in Whitley Bay, in the north east, was a young guitarist called Robb Weir. "My first band was called Trick," Weir remembers. "If I could go back in a time machine I would love to ask someone to film it, because the outfit was interesting if not hilarious: the singer was a punk, the bass player was into the Crusaders and jazz, the drummer – bless him – was called Fat Eric and he was a skiffle drummer. Because his kick drum wasn’t anchored to the floor, his kit used to separate halfway through every song. And there was me knocking out metal riffs of the day – Ted Nugent, Rush, Sabbath. I guess we must have done 40 or 50 shows locally before we stopped. But by that time – 76/77 – I had a real ambition to be in another band. I never wanted to audition for a band, so I decided to start my own band. I put an advert in the local Evening Chronicle saying ‘Guitar player seeking bass player and drummer.’"

The new band was called Tygers Of Pan Tang, the name taken from Michael Moorcock’s novel Stormbringer. "We played every weekend locally. We played in the clubs. We played half covers and half our own songs, which was quite risky, because the lasses dancing round their handbags weren’t sure how to dance to ‘Slaves To Freedom’."

There were musicians with the same need to make noise all around the country. In Birmingham, Brian Tatler had formed Diamond Head. "I’d been listening to Zeppelin, Purple, Sabbath, then newer bands like AC/DC, Rush, UFO and Van Halen appeared. I wanted to emulate the classic bands of the 70s, as most NWOBHM bands did. There were the big bands that would come through the Birmingham Odeon and we would watch those. It was inspiring to me that Black Sabbath and Judas Priest were from the Midlands, so it felt doable. it felt that if one of our own could make it, anything was possible."

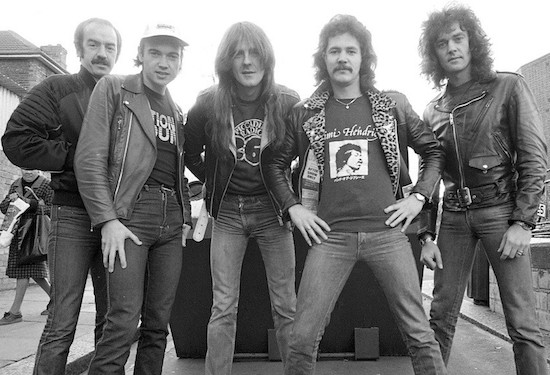

In Barnsley, there was a band called Son Of A Bitch, shortly to become Saxon. "We did working men’s clubs, the odd small rock club of maybe three or four hundred capacity," says their singer, Biff Byford. "The Boat Club in Nottingham was a big one. Anywhere there was lights and a PA. We didn’t have day jobs, So we were out and about all over the place. We were desperate for gigs. We’d stand outside the phone box waiting for the agent to call to say someone had cancelled. We got quite a lot of gigs from other bands pulling out. We played everywhere. I suppose it’s like being on Facebook now. A lot of bands try to post things that people will pick on and go viral. It was the same for us – we used to make our own posters and stickers and go out the night before putting them up. We were pretty ambitious."

And 16 miles south, in Sheffield, there was a young band called Def Leppard, with a glam rock fan singer, hard rock guitarists, and a desire to reach arenas. "The first thing we did was learn ‘Suffragette City’ by David Bowie," Elliott says. "That sets our stall out for the kind of music we wanted to make. We had to have something to play – this is when we were still a four piece. Having said that, Pete [Willis, guitar] was adamant we were going to do the Earl Slick David Live version, not the Mick Ronson Ziggy version. I was just happy to sing it. We did ‘Jailbreak’, ‘Emerald’ and ‘Rosalie’. We had an abortive attempt at ‘Only You Can Rock Me’. But straight away we were writing songs. Me and Sav [Rick Savage, bass] wrote ‘Ride Into The Sun’ within a month of us getting together. We didn’t have a rehearsal room, or a microphone, so we were a band in name, and it was least a month before we even performed a song. They didn’t know what I sounded like as a singer, but I was enthusiastic, tall and had a great record collection. What more do you need?"

Def Leppard

Despite their ambitions, the young Leppard were confined to their locality at first. "We hadn’t gone any further than Mansfield," Elliott says. "We’d played a place called Monsal Head, which was a biker venue in the middle of nowhere. It has to have been the premise for the Slaughtered Lamb in An American Werewolf In London. You shat yourself driving up to it, thinking, ‘I might never come out of this alive.’ But mostly it was the Limit Club, pubs, the Broadfield in Sheffield. The first gig we ever played was a school. The second was a field in front of 15 mates, and when it went dark they had to drive a car in front of us and turn the headlights on so people could see us. And then the third gig we opened for the Human League at the Limit Club, at a free festival, which meant we didn’t get paid, but they didn’t charge to get in. So the place was rammed. And we brought our own fanbase. We had 50 or 60 mates crammed at the front. That was mostly where we played. We played in Rotherham, we played a couple of gigs in a pub in Chesterfield. We couldn’t afford to go anywhere. You only got paid £20 and it cost you 30 to play the gig. Which is why we supplemented our income by doing the odd working men’s club, because they’d pay £350. It was one of those where Geoff Barton and Ross Halfin came to see us and we got the full page spread in Sounds, which kicked everything off. We didn’t play London until we opened for Sammy Hagar."

There were scenes, too, in the east Midlands, in the west country, in Wales, in Scotland. Anywhere, in fact, where there was somewhere to play.

Arguably the most important regional outpost, though, was the north east – home to Tygers Of Pan Tang, Venom, Fist, White Spirit, Raven and more – thanks to the presence of Neat Records, the Rough Trade or Fast Product of NWOBHM. David Wood had been running Impulse studios in Wallsend, recording whatever came around, when he had the idea in 1979 to set up an alternative label, using Steve Thompson as an inhouse producer. Its first two singles – one by a club band called Motorway, the other by an 11-year-old named Janie McKenzie – suggested a label with no idea what it should be releasing, or even what an alternative group should be doing. Enter a 16-year-old Conrad Lant, who had started working at impulse.

"I was going out to local bars at weekends to see bands," says Lant, who became better known as Cronos, the bassist and singer of Venom. "Oh, there’s a band called Raven, there’s band called Tygers Of Pan Tang. So I’m hanging around when they’re putting their gear away after a gig, and I’m saying, ‘Where the fuck did you come from?’ And they’re, ‘We’re just local guys, been playing for a year or two.’ Wow! So I was screaming at Impulse to get them in."

Tygers Of Pan Tang photographs courtesy of Rik Walton

Neat’s first metal release was Neat 03, ‘Don’t Touch Me There’, by Tygers Of Pan Tang. "I’d sent someone out to buy an Iron Maiden single," Wood says, "and said: ‘Can we get something that sounds like that?’"

"We were playing Whitley Bay High School, and David Wood came down to see us," Robb Weir remembers. "Afterwards he came up to us and said he loved us: ‘Do you want to come to the studio?’ We went down and recorded some demos. He loved them. And then he said, ‘Do you want to do a single?’ So we did ‘Don’t Touch Me There’. Dave took a chance pressing up 1,000 copies, and we sold them in three days. After that he had 5,000 pressed."

Down in London, the Soundhouse was going from strength to strength. After featuring the club in Sounds, Geoff Barton asked Neal Kay to provide a weekly heavy metal chart based on requests. "And then things started happening. Bands started sending me demos, and I put an ad in Sounds asking for demos, because I wanted to present an opportunity for bands to play the Wagon."

Def Leppard’s demo – the songs they released as the Def Leppard EP in January 1979 – came to Kay, and he gave them their first London show on one of the bills he put together at the Music Machine. But the crucial tape – the one that secured the Soundhouse’s legend – was recorded on the last two days of 1978 at Spaceward Studios in Cambridge, and brought in to the Soundhouse by the band. "Iron Maiden was what was needed," Kay says. "I started playing the cassette and all hell broke loose." The tape became a Soundhouse staple, topping the Sounds metal chart, and became Maiden’s first release – as The Soundhouse Tapes – in November 1979.

"I started shopping it around record companies," Kays says. "A&M laughed me out of the door – they said I didn’t know what I was talking about. I took it to CBS, who said: ‘This is a joke. This ain’t gonna fly.’ I got booted around and booted around, and in the end I went to EMI." Two Maiden tracks appeared on the patchy but important compilation Metal For Muthas, put together by Kay and EMI A&R man Ashley Goodall, and with Maiden’s longterm manager Rod Smallwood now involved, the group signed to EMI.

"Rod invited someone from EMI to the Soundhouse to see them," Kay says. "He said, ‘You have to see them in their home.’ So it was arranged that Brian Shepherd would come and see the band. Come the night, it was full. They had one hell of a following. Shep could only get in at the very back, and in front of him were some fans with a big banner, so he couldn’t see anything. He said: ‘I couldn’t see them, but I could hear them, and the people love them, so I’ll sign them. The night the cheque came through, we all went out to restaurant in Swiss Cottage. Rod had the cheque on him. It was for £40,000."

Through 1979 and 1980, NWOBHM became subject to an industry feeding frenzy, with managers and labels alike pursuing the rafts of bands. Saxon, with the aid of Trident – Queen’s management – signed to the French label Carrere. The success of ‘Don’t Touch Me There’ saw Tygers Of Pan Tang picked up by MCA. Def Leppard went with Phonogram, with the heavyweight management of Peter Mensch and Cliff Burnstein of Leber-Krebs behind them.

Neal Kay became a go-to man for those looking for talent. "Peter Mensch and Cliff Burnstein turned up one night on my doorstep in Colindale," he says. "I had no idea who they were. They knocked on the door at 11 o’clock and said: ‘We’re too late with Maiden. What else have you got?’ I reached for a bottle of Jack Daniels. I didn’t know if they were joking or not. I was just a fan who got lucky. So I went through my collection of demo tapes and I saw the light: Praying Mantis is that band! I pulled out their cassette and Mensch and Burnstein absolutely loved it. They asked me to arrange a meeting with Christian and Tino from Praying Mantis at The Bandwagon. And it took place on stage while I was trying to play records. Absolutely true. Peter was trying to persuade Tino and Chris to get a frontman and keyboard player to complete their sound. Their backing vocals were really good, but what Mantis needed was a frontman. Tino and Chris turned them down. Mensch was upset about that. The next day he called and said: ‘Can’t you make them understand? If we take them to America they will become very wealthy. You must tell them that.’ I phoned Tino, sat down with both of them and said, ‘The door is opening before you. You could be bigger than Iron Maiden because your music is radioworthy in the States, and these managers are two of the biggest names in rock right now. You can’t say no!’ But I’m afraid they did say no. Years later the boys would admit they made a mistake."

Poor old Diamond Head, though, missed the boat in the first wave of signings, even though they were one of the of the hottest bands of the time (they were, famously, Lars Ulrich’s favourite band), having been invited to support AC/DC in 1979 – with Mensch interested in looking after them – despite having no deal. Instead they were looked after by singer Sean Harris’s mum, and Reg Fellows, the owner of a local cardboard box factory (it’s no coincidence that Diamond Head’s self-released debut album was released in a plain card sleeve). "I would imagine they were being a bit unrealistic in their demands, and labels would probably say no," Brian Tatler remembers. "And maybe we had unrealistic expectations about what kind of a deal we could get – like Zeppelin signing to Atlantic for £200,000, and that was never going to happen. I didn’t really get involved in negotiations. I hoped the management knew what they were doing, and I would concentrate on writing songs. But shame on the labels that they didn’t spot that [self-released] album, because it became a classic, a very influential album."

Indeed it was. The highlight of Lightning For The Nations was ‘Am I Evil?’, a song that still sounds fresh today, heavy and inventive and melodic, and the early NWOBHM releases included a string of dramatic, tough singles and albums – Iron Maiden’s debut and its follow-up, Killers; Def Leppard’s On Through The Night; Saxon’s second album, Wheels Of Steel, with its brilliant title track and ‘747 (Strangers In The Night)’. Older bands responded in kind, too. Black Sabbath, with Ronnie James Dio replacing Ozzy Osbourne, released their best album in an age that same year, Heaven And Hell, whose lead single ‘Neon Knights’ owed an audible debt to NWOBHM; the band Dio had left, Rainbow, cast aside the swords-and-sorcery epics for the sharp, commercial hard rock of Down To Earth (1979), getting their first top 10 singles (‘Since You Been Gone’ and ‘All Night Long’) in the process; one of Ritchie Blackmore’s erstwhile Deep Purple singers, David Coverdale, achieved a commercial breakthrough in 1980 with the third Whitesnake album, Ready An’ Willing, while the other, Ian Gillan, after several years casting around for a purpose, focussed on hard rock with his band Gillan and became a Top Of The Pops regular.

Saxon

A new ecosystem sprang up around metal’s resurgence, too. The Reading festival had been a confused mishmash in the late 70s, and violence between metal fans and new wave fans at the 1979 event (headlined by The Police, Thin Lizzy and Peter Gabriel) saw the event tip decisively in favour of metal the following year, with the few non-metal and hard rock acts outnumbered by UFO, Iron Maiden, Krokus, Praying Mantis, White Spirit, Samson, Tygers Of Pan Tang, Angel Witch, Sledgehammer, Girl, Magnum, Budgie, Def Leppard and Whitesnake. That year also saw the first Monsters Of Rock festival – with Rainbow, Judas Priest, Scorpions, April Wine, Saxon, Riot and Touch – and the establishment of Castle Donington as metal’s greatest site of live music pilgrimage, a status it retains today. Neal Kay, naturally, was the compere.

A media sprang up around it, too. Geoff Barton’s writing in Sounds was crucial, and that was followed in June 1981 with a one-off supplement called Kerrang! – edited by Barton – which immediately became a monthly magazine. And then there was The Friday Rock Show on Radio 1, from 10 to midnight once a week, with Tommy Vance presenting.

Although, as Joe Elliott points out, hard rock had already had a home in Alan Freeman’s Saturday afternoon Rock Show on Radio 1, that ended in August 1978, just as NWOBHM was beginning. "I came back and said, ‘OK, we need another rock show,’" says Tony Wilson, who produced both Freeman’s show and The Friday Rock Show. "I had a look round at various potential DJs and Tommy ended up being the most obvious, and I got the go-ahead to start what turned into The Friday Rock Show. Inevitably, NWOBHM was a great part of the focus of the early days, because that’s what was happening."

The first show went out on 17 November 1978. At first, Wilson and Vance used old Peel sessions in the programme, but within a year the NWOBHM bands had started coming in to Maida Vale to record sets for Vance and Wilson. Def Leppard, Praying Mantis, Samson and Iron Maiden had sessions broadcast before the end of 1979; Angel Witch, Girl, More, Saxon, Diamond Head, Sweet Savage and Tygers Of Pan Tang would be among those who followed suit the next year.

"We used to get a lot of demo tapes, and listening to them was a task and a half," Wilson says. "Labels would bring bands. Both Tommy and I were avid gig-goers, too. So it was a bit of all that. What we were looking for was originality, excitement – you know when you hear something. It kicks something off in you: this is fucking good. A lot of instinct. An awful lot of bands just don’t have enough strong songs: it’s not easy. The big groups stood out from an early stage, absolutely they did. Maiden, Saxon, Leppard. But there were more that we promoted that didn’t get anywhere near as far."

Top Of The Pops got on board, too. Iron Maiden were the first NWOBHM band on the show, performing ‘Running Free’ live in February 1980. They were followed by Saxon – who became regulars – performing ‘Wheels Of Steel’, though they didn’t get the whole awkwardly-dancing-fans treatment. "We did it in a studio with no audience," Biff Byford says. "There used to be a mid-chart position and if you got in there, nearly in the top 30, they recorded a Top Of The Pops song for you, before the show proper. A lot of bands went and did it, and a lot didn’t get used because the single didn’t go up. But ours did, so they played it. We didn’t get the green room or anything. We didn’t get to meet other bands. It was all a bit workmanlike. The first Top Of The Pops was a bit of anti-climax because there was nobody there and they wouldn’t let us play live. But if you were going to be big you had to be on Top Of The Pops."

In 1981, two years after the first wave of NWOBHM bands had started to break through, the most extreme band to come out of the movement – though they deny any kinship – made their first recorded statement. Venom’s ‘In League With Satan’ is an extraordinary, murky single, the first in a string of records that inspired extreme metal throughout the 80s. While it was the celebration of Satan than won them the column inches and the notoriety, Cronos’s motivations were more rooted in showbiz.

"We just wanted to put on a spectacle," he says. "I had a big problem with people being content sitting in the clubs. I used to see bands and think, ‘You’re massively talented, but you’re just sitting in this club getting your fifty quid,’ and I never understood it. I wanted to go the opposite way. I wanted to be the Kiss of Newcastle. People said there was no way I could do that, so I wanted to do it. That was the reason behind the leather and the studs, and all the time spent sewing and putting in studs, and getting bleeding fingers. And all the time creating these big drum risers. People would say, ‘Venom are only doing it for the money.’ Do you realise how much a Venom show costs? We could have easily put on a much smaller show and pocketed enough money to buy decent-sized houses. There were whole tours we lost money on. When we finished the American tour in 85 with Slayer, the fucking lighting company wouldn’t let us take our drums or guitars home with us because we owed them that much money. We went home with our clothes."

Without major label backing – given Cronos worked at Impulse, it made sense for Venom to put their records out on Neat – Venom were forced to take a DIY approach to being the Kiss of Newcastle, to the extent of making their own pyro. "We had these steel pots that were about six inches. We got some wooden boxes made, put three steel pots in each box then filled the box with sand. We ran cables underneath. There was a local shop that used to sell Le Maitre firework effects and we would buy as many as we could afford. We’d open them up, pour the gunpowder into these pots. We’d make a fuse from a tiny piece of cable between the live and neutral wires, stripped back, plug it into the wall and then that goes in the bottom of the pot. When you flick the switch on the wall, it cracks the fuse and boom! You have an effect. There was a lot of trial and error. We brought the ceiling down in one rehearsal room. We had a couple of pots set up. We put a bit too much gunpowder in. Flicked the switch, lights went out, the ceiling came down on top of us. We were rolling around laughing on the floor. But we could easily have killed ourselves. We avoided one disaster by the skin of our teeth. That was in Staten Island, the first shows Metallica did with us. One of the pots we’d loaded full of explosives flew up and buried itself in the wall beside the balcony seats. Luckily there weren’t many people in the balcony – they were all downstairs going mental. It was buried in the wall: it flew off the stage into the balcony. If there’s been someone sitting there, or had the pot been a bit to the left, it could have killed somebody."

"I went to the first Venom gig, in a church hall in Wallsend," Neat’s David Wood remembers. "They had the pyro and smoke machines and set it all off, and for the entire set no one could actually see the band. They could be very extreme. The repair bills for theatre ceilings from pyro … They would have been better off with a bigger organisation with loads of money to throw at them."

Cronos says other bands on Neat – the ones who’d paid their dues in the clubs – were dismissive of Venom. Couldn’t play, couldn’t write a song, no talent. "I knew those guys from doing sessions with them for Neat, but as we started getting attention they got more hostile. I used to say, ‘It’s not my fault the fans dig what we’re doing more than you. We’re doing something new and different and you guys aren’t.’"

Elsewhere, though, friendships were born. Joe Elliott remembers he and Leppard going to Retford Porterhouse to see Iron Maiden when they made an early excursion north, and establishing a lasting friendship with Maiden bassist Steve Harris. Another relationship forged in the early days of NWOBHM – with the London band Girl – would eventually lead to Girl’s Phil Collen joining Leppard and becoming a crucial creative part of the group as they ascended to US superstardom with 1983’s Pyromania album.

"A lot of those people relied on each other, so I don’t remember too much negativity," Elliott says. "I’ve always supported the underdog, and when Girl came out, they got flak in the media because [singer] Phil Lewis was dating Britt Ekland. Can you not see past that and listen to the songs? Phil Lewis and Phil Collen came and stayed at my mum’s house after their Sheffield show, because their hotel was in Buxton. Don’t know why. We went out on the town. There was this NWOBHM band called Sledgehammer playing the Genevieve, which is a disco. We went down and we were fucking hammered. We went down to the dressing room and said, ‘Can we borrow your gear?’ And the four of us decided to be a band for the night. I went on drums, Phil Lewis sang, Phil Collen played guitar and Steve [Clark, Leppard guitarist] played bass. And we blagged our way through ‘You Really Got Me’. We tried to play ‘Do You Love Me’ by Kiss, but Steve fell asleep on the drums. These were great bonding moments. My mum woke up the next morning and said, ‘Who’s that who stayed in the spare room? There’s mascara on the pillowcase!’ ‘Yes, that’s my friends from the band Girl.’"

By 1983, NWOBHM’s golden moment had passed. While Iron Maiden had established themselves as the dominant pure metal band in Britain, perhaps the world, and Def Leppard were poised to become a bright and shining monolith of pop-rock in partnership with the producer Robert John "Mutt" Lange, the other bands were seeing their moment slip away. After a No 9 hit with 1982’s album Denim And Leather, Saxon’s chart positions began to slip with each successive record. Tygers Of Pan Tang had reached No 13 with the 1982 album The Cage, but never reached the charts again. Diamond Head didn’t get their major label debut until 1982, and then followed it up with a prog-influenced LP, Canterbury – the first 20,000 copies of which were mispressed and jumped – and their momentum was fatally stalled. And the scores of bands who had emerged in 1979 and 1980 faded and gradually disappeared, as metal trends moved towards the thrash that Venom foreshadowed, and the hair metal that Def Leppard were an outlier for.

But NWOBHM’s legacy never disappeared. All the big American thrash bands were openly inspired by it. In Switzerland, a young band called Hellhammer were taking note of the speed and aggression of the best NWOBHM bands, and mutating it; a few years on a bunch of Norwegian bands took inspiration from them, and from Venom, and the second wave of black metal was born, itself spreading ripples around the world. And Leppard and Maiden still fill arenas around the world, 40 years on.

"Sometimes things just have a natural energy, and you can’t say why it happened," Joe Elliott says. "We were all in the same headspace and had the same thought process going on. It’s just that Maiden were doing it in London, we were doing it in Sheffield, Diamond Head were doing it in Birmingham, Tygers were doing it in Newcastle, Vardis were doing it in Wakefield, Saxon were doing it in Barnsley."

"These were some of the greatest times of my life," Neal Kay says. "I’m sorry I couldn’t help everybody. But at least we woke up the industry and gave them a kick in the nuts, and helped establish a counterculture that went mainstream. We showed the media they didn’t know what they were doing. For me the job was done."

Jobcentre Rejects – Ultra Rare NWOBHM 1978-1982 is out now on On the Dole Records. Volume 2 by Def Leppard is released on Mercury on 21 June. The Coffin Train by Diamond Head is out now on Silver Lining Music; they play Camp Bestival on 25 July. The Venom boxset In Nomine Satanas is out now on Sanctuary