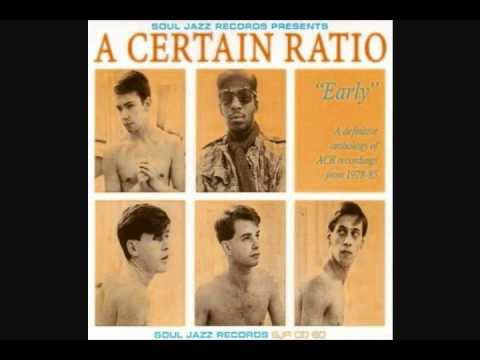

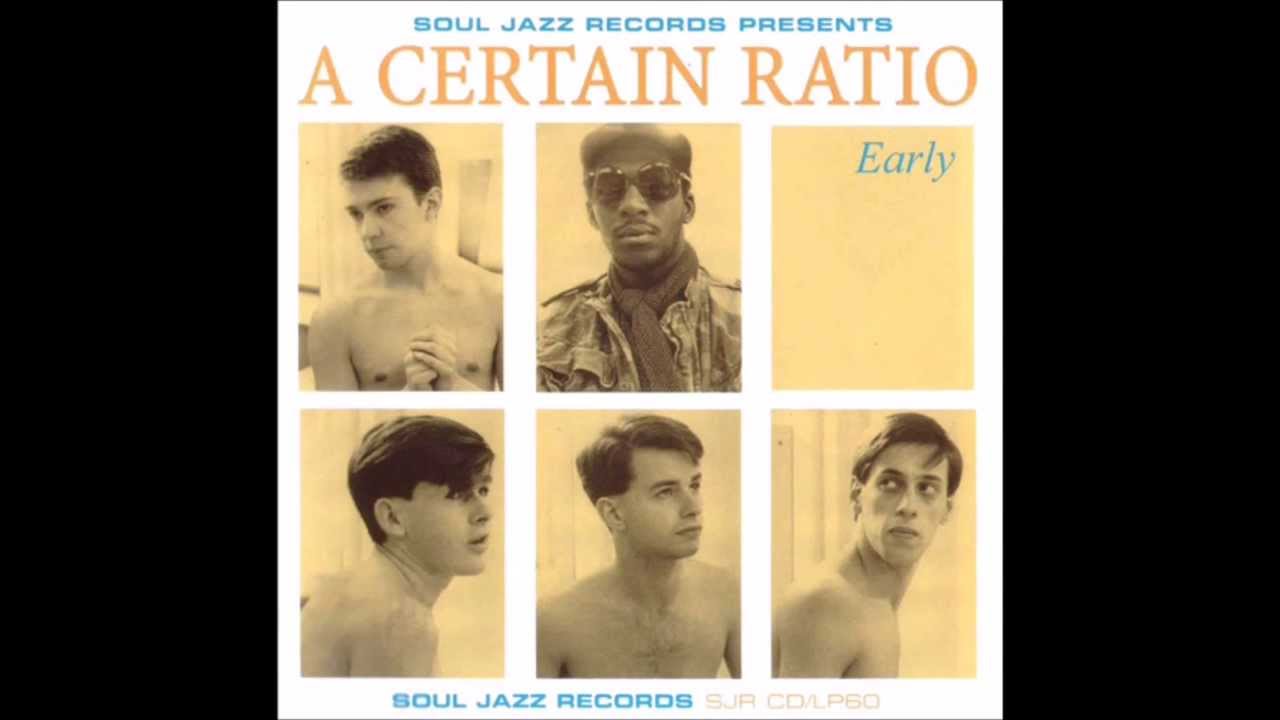

ACR photography by Kevin Cummins

The Factory Records narrative has been distilled down in the popular consciousness so successfully that it tends to only concern a handful of names. Ian Curtis, Tony Wilson and Shaun Ryder.

But there’s a case to be made that the relatively ignored A Certain Ratio are the most quintessential figures in the Factory history. As with the label, contradictions pulsed through their veins. Here was a funk group as monochrome as the Manchester skyline yet one possessing a molten groove that melted through the gloom. They have never had a hit but, with a new box set to be released on Mute in May, they have outlasted most of their peers.

They were fearlessly uncommercial and just like Factory, they emerged a fully-realised triumph of both style and substance – a synergy of flash and follow-through.

ACR’s dapper, militaristic dress sense was a running joke through Michael Winterbottom’s postmodern 2002 Factory biopic 24 Hour Party People. And it was undeniable that they did look like a bit Spandau Ballet, if Spandau Ballet were into neoplasticism and Italian futurism and saw a cheeky trumpet solo as subversion of chart orthodoxy rather than a gimmick to get on Top Of The Pops. Decades before microhouse, they made minimalism you could dance too.

"People either loved us or completely hated us," says singer Jez Kerr. "But that had more to do with Factory and (label co-founder) Tony Wilson than with the band. A lot of people hated him as well. Because of Ian and the Factory legend we get written about a lot more than other bands. The truth is that nobody knew what was going on. I’ve read a few things on the internet saying we planned everything. Nobody knew what the fuck they were doing. That was the beauty of Factory – the chaos."

1. ‘All Night Party’ (1979)

Jez Kerr, vocals: Our first single. As with most bands in Manchester, we started through the Musicians Collective, which was funded by the Arts Council. On Monday nights at Band on the Wall on Swan Street, musicians could play for free. And they’d give you a little bit of beer. Joy Division, The Fall – a lot of people played their first gigs there.

Like all those young bands we wanted to get a record out. We were fortunate to meet Rob Gretton, Joy Division’s manager, and Tony Wilson from Factory. Tony was a bit smart or smarmy. He could be condescending at times. He definitely had the gift of the gab. He could sell anything. He would just talk for hours and say some ridiculous things. But you would always listen.

At that point ACR couldn’t really play. We were into the Velvet Underground, Throbbing Gristle. That’s what we sounded like on ‘All Night Party’. Young bands are different now. They are very savvy in terms of what avenues to pursue. Back then, nobody knew what was going on.

We signed for Factory because it was the only option available. Rob Gretton saw us at Band on the Wall and told Tony to put us on at Russell Club in Hulme – the Factory Club, as it was known. We played there supporting The Fall. After that Tony asked us to do a single. We went to Cargo Studios in Rochdale. That was the first time we met Martin Hannett. We recorded ‘All Night Party’.

Martin was quite out there. We fought a lot. He had his picture of the sound he wanted the musicians to record. Being arrogant youngsters we wanted our say as to how it should be recorded. There was lots of friction. In hindsight, some of the stuff we did with Martin Hannett was great. Some of it it missed totally.

At the end of the day we just couldn’t get on. He wanted to do it his way. We wanted to do it our way. Which is a shame really. To Each… , which was produced by Martin Hannett, is a great album.

2. The Graveyard And The Ballroom (1979)

Donald Johnson, drums: It was Tony Wilson’s idea to put this out on cassette. Bow Wow Wow had done a cassette album. And Tony didn’t want Malcolm McLaren to have the only cassette-only release. It was a great idea. Cassette was very inexpensive. Factory had some bad experiences with vinyl early on. Not anybody’s fault – just what happened back in those days. Tony was a fan of McLaren and liked the idea.

Tony and Alan Erasmus [Factory co-founder] would be around the studio. Tony thought that because he could direct TV cameras he could direct the studio, which is not the same thing. We were very young and trusted Tony. Him and Alan were completely different. Alan doesn’t do publicity. Doesn’t like to take credit for anything. He’s a really undercover guy. Not at all the same as Tony.

You have to remember Alan was an actor. His outgoingness came out in his acting. He could push all of that into doing television or a play. In normal life, he was Mr Quiet. Nobody knew he was in the room. Tony, because he had a weekly TV programme… well, some people said he was arrogant. He was just confident at the thing he was doing. It’s always a thin line between confidence and arrogance.

The version of Tony played by Steve Coogan in 24 Hour Party People was very much a caricature. The whole movie was a caricature. People like Steve find the strongest trait in a person and exaggerate that.

It was the same with us in the film, wearing the shorts and all that. The famous quote of ours from the movie, "I’ve got better clothes than Joy Division." It was tongue-in-cheek. 24 Hour Party People was a very heightened version of reality.

3. ‘Do The Du’ from The Graveyard and the Ballroom (1979)

Martin Moscrop, guitar, trumpets: It was a long time ago now but I remember we were really driven by Tony Wilson who was very, very into the band. He didn’t waste a single one of our recordings. Everything we did he really loved and he put out.

We went to Graveyard Studios and put down the tunes we’d written and were playing live. We were really well-rehearsed from gigging. Everything was done virtually live. We’d record as a band and overdub the vocals, trumpets and percussion.

There wasn’t a lot of room for production. So even though Martin Hannett produced that side of the record (side b is a live recording from the Electric Ballroom), he wasn’t able to put his stamp on it. It sounded like proper ACR. Whereas when we did To Each…, the record after that, it really had the Hannett stamp because it was properly produced.

It’s the rawness that makes ‘Do The Du’ and everything else on the album. It’s ACR in a very protean state. A lot of the tracks were written prior to us getting Donald in as drummer.

Around that time we supported Talking Heads on their UK tour. That came through Tony. He presented a music programme called So It Goes. He also used to get a lot of bands – the Sex Pistols, Blondie – and put them on Granada Reports, the local news broadcast on a Friday. The band that got on would also then play the Factory on a Friday night. So as well as the Factory they’d get on TV. That was a big pull for record companies and bands.

We did five dates with Talking Heads. The Human League were going to do it but Talking Heads management found out at the last minute they were just going to show projections and not actually play, so they got sacked. They had to get another act in and luckily we were chosen.

So we went from doing those Factory package gigs – maybe with Durutti Column and Section 25 – to doing the Talking Heads tour. We played the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, which used to then hold about 2,000 people. David Byrne liked us. He would stand in the wings at each gig. Whether Talking Heads were influenced by us is another thing. We were quite influenced by then. They were more rock than funk at that point.

They thought we were absolutely bonkers. When we started we didn’t have a guitar tuner as it was a really high tech thing. They let us use theirs. It was quite a revelation for us, being in tune. Of course the Factory connection continued as Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth would produce the Happy Mondays, though that was many years later.

4. ‘Tribeca’ video (1980)

Jez Kerr: The first time we went to New York, we spent three weeks in a studio in New Jersey. We were staying on Hudson Street. Chuck, the guy who owned the building, was later in Goodfellas. The guy with the hairpiece trying to get the money off Robert De Niro and gets garrotted in the car… that was him.

De Niro’s loft, as it happened, was on the top floor of the building we were staying in and Harvey Keitel was staying there. When we were filming the video we were making a real racket with percussion and trumpets. Harvey Keitel knocks on the door asking how long we were going to be. He was annoyed because he was wining and dining a lady and we were interrupting his evening.

A guy called Michael Shamberg directed the video. He did quite a few videos for New Order. He was a friend of Tony’s and tour managed us when we went to LA in 1983. He filmed us at Hudson Street playing percussion and intercut it with the first gigs we did in New York.

We also did some filming on Wall Street. I’m sure the footage still exists somewhere. We went into this garage – just off the street and without any permission. We got out of the back of the van and started playing trumpets and snares. This security guard came out, threatening to shoot us. And meanwhile Michael was filming from the van. I’d love to see it.

New York was Tony Wilson’s idea. His mum had died and left him some money. He used that to fund the tour and pay for the studio. We were very fortunate to have someone who believed in us and loved the band. Major labels wouldn’t look at us back then. We were too bizarre.

5. ‘Shack Up’ (1980)

Donald Johnson: The second single and my first recording. ‘Shack Up’ was a cover of a song originally released by Banbarra in 1975. Our version came about for a lot of different reasons. I knew the track through my friend Leroy Richardson, who would go on to manage the Hacienda.

When I joined ACR I discovered the other guys liked it too. It was one of those weird coincidences. Our version would have come about from the fact we were all listening to it in the rehearsal room and decided to make it our own. It’s one of those tracks that has stuck with us, much as ‘Step On’ has with the Mondays.

What I like about it is that it’s very simple. In A Certain Ratio we were trying to play funk and to communicate the idea of what funk is. This was the perfect vehicle. The song had been out in nightclubs a little while and it had a very strong riff. The weird thing is, years later, the riff from our version has been used on so many tracks it’s incredible. It’s been sampled all over the place. I was listening to Radio 6 with my wife the other day. All of a sudden I hear the riff. Hold on, that’s ‘Shack Up’. I didn’t even know what song it was. ‘Shack Up’ has done us proud.

6. ‘Flight’ 12" (1980)

Jez Kerr: ‘Flight’ was our first 12 inch and the perfect marriage of Martin Hannett’s style and our style. As I recall, we did it at Revolution Studios and mixed it at Strawberry Studios. Like a lot of our songs, it had its origins with us all playing in a rehearsal room.

We’d had it for a while and a version appears on Graveyard And The Ballroom. We’d done that in Prestwich on a four-track. That’s our version. Martin produced the 12 inch and it’s completely different – very dreamlike. At that point we were gaining some notoriety. When Ian Curtis died, it really catapulted Factory’s profile and created a lot of interest. I’m sure we would have still been written about, even had that not happened but that made it more dramatic.

Joy Division were such a great band. Everyone in Manchester knew they were the best band in the city. Ask anyone from that era who was the best band in Manchester and they all say Joy Division. I saw them play and sometimes they were shit but most time they were great. It’s the mark of a good band that starting out you can be crap but at other times totally brilliant.

Rivalry certainly existed. You think you’re the best in the world and that everyone else is shit. We shared a rehearsal room with Joy Division for about a year in Salford.

There was a lot of messing about. When they left the rehearsal room for the last time, they took out the fuse-box. It was pitch black. And somebody had left a pig’s head on my amp. They were famous for practical jokes, something they learned off the Buzzcocks. There was a lot of that – lots of juvenile daftness.

7. Four For The Floor (1990)

Martin Moscrop: When we signed to A&M I convinced the band to invest some of the advance. It was the most money we’d had in our lives but we put £10 to £15 grand into setting up a studio, this new premises, just off Pollard Street. Our first album for A&M was Good Together. They spent loads of money on it and it was very good – but also very smooth, not quite like what ACR tended to sound like.

After Good Together, we wanted to show the other side of ACR. The great thing was even though we’d spent a lot of money on the studio we charged A&M more than that for using it. So the studio paid for itself and made money. We didn’t have the record company behind us. Our a&r man was the only person on the label who understood what we were about. He couldn’t do it single-handedly. He was fighting lots of other departments. After we were dropped, we went to see Rob Gretton.

So then we signed with his label Rob’s Records and did a lot of stuff there. Up In Downsville was recorded at Soundstation. A&M was a totally different experience, after coming off Factory. With a major label, there is so much politics. You’re fighting the marketing department, the a&r department, the distribution department. All these different departments with different ideas as to how you should be pushed. Most of the didn’t have a clue.

Rob was good to us. Everything we produced, he released. And whenever we were in financial difficulty – say we owed six months rent on the studio – he’d bail us out. He really helped Soundstation. If he had a new act he was going to record, he’d call us first. He knew that would generate some income.

8. ‘Mello’ from Up In Downsville (1992)

Donald Johnson: The problem we had working with Martin Hannett was that, as good as he was, as much of a genius as he was, he didn’t recognise where we wanted to go. Where we wanted to go was a different place from where he was.

That transition point was difficult. You have young upstarts and this seasoned professional. The flavour he was adding, it didn’t suit us, even though it might suit an indie band. I mean, come on, ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ – my favourite song in the whole world.

But ACR were moving away from that – from the ethereal, the eclectic weirdness, the weird echoes. We were into big ensembles like Cameo and Funkadelic. Martin, to his credit, knew about that stuff. But Martin did Martin, as good people do. They don’t veer off that thing they’re good at.

With ‘Mello’ we wanted a cinematic element. But we also wanted a real hardcore dance element. That was the difference between us and New Order. They did it with electronics. That isn’t so slag them off – New Order used to lend us their equipment. But what they did with electronics we were looking for within our sound. We wanted to be warmer. But still scratchy, still getting under people’s skin.

I remember when Spandau Ballet did ‘No. 1 (I Don’t Need This Pressure On)’. They were using brass and people were going nuts. We’d been doing that! But we weren’t trying to be like Spandau. We were trying to be a harder version of what we were. I would never belittle Martin but it just didn’t work for us.

9. ‘Manik’ from Up In Downsville (1992)

Martin Moscrop: Up In Downsville was supposed to be our next A&M album. Our a&r man and some big cheese from the label came up to Strawberry for a playing session. When you’re recording you don’t send the label the tracks as you’re doing them. You want them to hear the finished thing. We’d more or less completed the album. The first song was ‘Manik’. It really was manic – really out there. We put it out on Rob’s Records instead.

The Manchester thing was quite big at that time. We weren’t new but all the majors were signing Manchester bands. A&M signed us and didn’t know quite what to do with us. We didn’t have a clue what to do with us either.

That was part of the longevity. We’ve never been very successful, which has helped. When a band becomes successful, that’s when they tend to have a falling out. Success brings pressure. For me, making a record is a success.

The Happy Mondays used to rehearse to us next door. They were really into what we were doing. The whole acid house thing – quite a bit of that rubbed off on us as well. When the Hacienda first opened we all lived less than a mile away. All the Factory bands had honorary membership. We used to use it as our local boozer. You’d go there for a few beers.

This was all pre-acid house. When acid house came along, it was like being 16 again when punk rock was happening. Here was this totally out-of-the-blue thing that just blew up. The Hacienda was great up until around 1991 or 1992. That’s when it went more commercial and you had a lot of that handbag house.

10. ‘Houses In Motion’ from ACR:BOX (2019)

ACR portrait by Paul Husband

Martin Moscrop: Our label manager at Mute, from day one, said they wanted to do a box set with us. They wanted to put out lots of unreleased stuff. There are hundreds of unreleased tracks, that range from demos to different mixes. We had two versions of Talking Heads’ ‘Houses In Motion’.

The idea was for Martin Hannett to produce them as demos, for Grace Jones to sing. She came into Strawberry Studios the night after she slapped Russell Harty on television. She really liked the recordings. The plan was to go to the Bahamas and record an album. But of course Chris Blackwell was Grace Jones’s producer, not Martin Hannett. The rumour was that, when Chris Blackwell found out, he said, "No way, it’s not happening."

Grace Jones was bonkers, absolutely bonkers. She had these two guys with her. Her whipping boys, the record company called them. She was bossing them about. This was back in the 1980s. It was a Sunday night. All the pubs shut at 10 o’clock. She instructed the two whipping boys to go and buy a bottle of wine. They told her it was impossible – everywhere was closed.

But she wanted a bottle of wine. They went out and came back a couple of hours later. They’d driven around in a taxi and eventually found an Indian restaurant that sold them a bottle of wine. Did we make her a cup of tea? I don’t think tea would be good enough. She was quite bonkers.

I also remember Madonna opening for us, at the Danceteria in New York in 1982. It was the end of our tour. She had Jellybean, her producer, with her. He set up a four-track tape machine at the back of the stage. She had two dancers. He pressed the tape and she sang, with a dancer either side.

We get asked to do a lot of Factory-type nostalgia gigs. But we’re constantly looking for new things. It’s like New Order. They play a couple of Joy Division tunes because that’s what fans want. But that’s not where they are at. Whenever the tour, they always have a new act as support.

People want to hold onto the Factory thing, the Hacienda thing. Hacienda Classical, Hacienda on Ice… We’re not interested. For us, it’s always about moving forward.

ACR:BOX is released via Mute on May 2. A Certain Ratio play numerous live shows and festivals in Britain this year