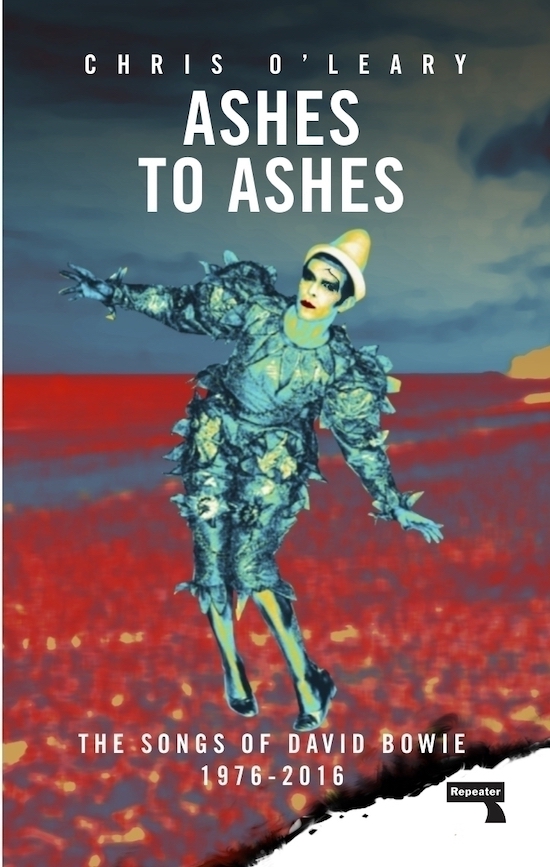

By Jean-Luc – originally posted to Flickr as David Bowie, CC BY-SA 2.0

Chris O’Leary’s new book, Ashes to Ashes completes an epic trawl through the David Bowie songbook, track by track, moment by moment, each carefully digested, parsed, and analysed through the author’s unique lens.

Picking up where 2015’s Rebel, Rebel left off, Ashes to Ashes follows Bowie’s career from 1976 to the end of his career over 800 pages of brilliant prose.

The Quietus caught up with the author to find out how, why, and to what end he did it. The interview is followed by an extract from the book, working through the psychic resonances of ‘Sound and Vision’.

Why Bowie?

Once I set upon doing a single artist, chronological, song by song thing, the number of candidates soon diminished. You needed some longevity but also a decent variety in terms of musical style, or you’d get bored out of your mind at some point and give up. Neil Young’s catalog was too long and woolly to deal with; Pete Townshend, another contender, basically ends in the late 1980s. So Bowie soon seemed like the best choice. What did it was finding in a local used record store a compilation of his ’60s singles, which I’d never heard before. That was a big part of it – there were decent stretches of his career I didn’t know at all and was curious about.

When were you first introduced to the music of David Bowie?

I’m an American who grew up in the South in the late 1970s and 1980s, and so I think my experience of Bowie as a kid was greatly different from say, that of someone in the UK in the same period. He wasn’t on the radio in Virginia very much until ‘Let’s Dance’ – I think I vaguely knew ‘Space Oddity’ and ‘Ziggy Stardust’ but it wasn’t like even those songs were played often. My parents had none of his records.

So it was the 1983 singles, and more importantly their videos – MTV was everything to me that year – that did it. But at the time I classed Bowie as being a slightly older looking member of this bright group of ‘new’ musicians: Duran Duran, Eurythmics, Adam Ant, the Fixx, Cyndi Lauper, Thompson Twins, and so on. He was part of that set – he didn’t seem aligned (as he actually more was) with, say, the Stones.

What prompted you to start this project in the first place?

I was tired of doing a sprawling blog that, rather ambitiously, was trying to cover the entire twentieth century in music. I wanted a more controlled, precise thing to write about. A sort of mild self-therapy/distraction programme I did in the mid 00s during a rough stretch of my life was to use Ian MacDonald’s Revolution in the Head book as a way to “re-listen” to the Beatles – every day or so at lunch, I’d listen to a song and read the respective entry. It was just something to do, but it made the music fresher to hear it in that way. And I thought the MacDonald template could possibly work when applied to another artist.

Why did you choose 1976 as the dividing line between the two books? What changes then? And in what other ways might you characterise in a general way the difference between the two halves of this project?

The first book had two logical endpoints – Station, as it turned out, or with the Scary Monsters songs. And as it was already an overlong manuscript just up to 1976, it ended with Station. In retrospect, I’m glad it did: I think it works well. The Berlin songs have more in common with his later work than they do with, say, Young Americans. It’s also a more coherent narrative to have the first book end with the ‘crashing in the same car’ LA period and the next to start with DB in the recovery room.

The first book is more of a traditional “it’s a long way to the top if you wanna rock ‘n’ roll” story – how one odd, talented, and at times unlucky musician struggles to find a place in popular music and finally does it, at a pretty grievous cost to him at times. the Ashes book is more a long set of ups and downs – periods of struggle, great fame, of slack, of fitful attempts to recapture the past or to try to move on – until Bowie’s comeback and death in the 2010s gives it a pretty grand ending.

Having reached the end of this journey through Bowie’s catalogue, are there any broad lessons you have been able to learn about his oeuvre as a whole? Do you feel differently about him as an artist now?

How strong and unique a songwriter he was. I’d try to figure out a particular song and sometimes ask a musician friend what on earth was going on in a particular section, and it would often be “huh, why is he moving there? why that chord?” It finally would make sense to us, often in a surprising way. He often worked, in a musical sense, in this continually fresh and strange way. Perhaps intuitively; maybe because he often got bored doing the same thing over and over again, and would find ways to make things more interesting.

I think the idea of “David Bowie” was as fascinating to him at times as it was to his audience. I think he liked toying with the mythos, referencing his past, creating new variations, etc. Maybe one reason he came back in the 2010s was that he knew his character needed some stronger closing chapters. He said he always wanted to direct films and this was sort of how he did it.

What’s your favourite Bowie song? And why? Has your answer to this question changed pre- and post- this project?

I always say ‘Queen Bitch’, and still do. And for no reason other than I’ve always loved it.

Sound and Vision

Recorded: (rhythm tracks) ca. 1-20 September 1976, Château d’Hérouville; (vocals, overdubs) October-18 November 1976, Hansa Tonstudio 2. Bowie: lead and harmony vocal, Chamberlin M1 and/or ARP Solina (“synthetic strings”), baritone saxophone; Gardiner: lead guitar; Alomar: rhythm guitar; Young: piano; Eno: backing vocal; Murray: bass; Davis: drums; Mary Hopkin: lead and backing vocal. Produced: Bowie, Visconti; engineered: Thibault, Meyer.

First release: 14 January 1977, Low. Broadcast: 2 June 2002, Top of the Pops 2; 15 June 2002, A&E Live by Request. Live: 1978, 1990, 2002-2004.

Some time ago, my marriage fell apart. A salve for personal catastrophe is routine. Life is reduced to minor actions. Today I will arrange the bookcase. Tomorrow I will go to the store. Tonight I’ll listen to this record. But what to listen to? Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks was a war correspondence, as was Richard and Linda Thompson’s Shoot Out the Lights. Those records had too much pain, and I’d had enough already. What I played, over and over, was Low, and what I played on Low, most of all, was ‘Sound and Vision’.

The small pleasures of an unexpected solitude. Bowie called ‘Sound and Vision’ his “ultimate retreat song.” “It was wanting to be put in a little cold room with omnipotent blue on the walls and blinds on the windows,” he said. (“Deep blue was the colour that I took to every dwelling,” he wrote in an autobiographical fragment in 1975). On the set of The Man Who Fell to Earth, he sat alone in the desert sands for hours, listening to records on a hand-cranked gramophone. Low, he said in 1977:

[…] was a reaction to having gone through… that dull greenie-grey limelight of America… and its repercussions; pulling myself out of it and getting to Europe and saying, For God’s sake re-evaluate why you wanted to get into this in the first place? Did you really do it just to clown around in LA? Retire. What you need is to look at yourself a bit more accurately. Find some people you don’t understand and a place you don’t want to be and just put yourself into it. Force yourself to buy your own groceries.

‘Sound and Vision’ opens in a locked room. Everything is in its place, a clockwork song. Two guitars, panned to either channel; piano; exuberant bass; Harmonized drums and whooshing percussion (a processed snare) that sounds like a radiator coming to life. Then a descending synthesizer line, and sighs of delight. A song is assembling itself: rhythm section, then “strings” (ARP Solina), then backing vocals, then brass, until its composer appears, as if called to the stage to take a bow.

It had started with Bowie giving a simple descending-by-fifths G major progression to his band, and singing a few melodies, offering a few bassline and drumline ideas. Dennis Davis “thought it sounded like a Crusaders tune” (possibly ‘Stomp and Buck Dance’), while George Murray heard Bo Diddley. The band cut the backing tracks with their usual economy; a few takes, done.

It’s shot through with little moments of joy. Mary Hopkin’s cameo appearance, for which the whole piece has been waiting; Bowie’s baritone saxophone, an old friend showing up unexpectedly; Davis’ drum fills as a string of firecrackers; Bowie’s opening phrase, a sleepy rise and fall over an octave (“don’t-you-won-der some tiiii-i-ii-i-ii-i-i-i-iimes”), as if he’s been listening along and started singing, carried away by what he’d set in motion. There’s a precision to his vocal, of having to plot his course exactly, keeping to his lower register and doubled at the octave. He underscores flights of fancy (the long-held ooooos) with glum, nearly-spoken phrases (“nothing to say”).

While Brian Eno mainly has walk-on roles on Low’s first side, he suggested the structure of ‘Sound and Vision’, telling Bowie to hold off from singing until things were underway (1:30, the halfway mark), to confound listener expectations. As the side starts and ends with instrumentals, ‘Sound and Vision,’ parked midway in the sequence, appears to be another one at first. Eno had used a similar trick on his ‘Here Come the Warm Jets’ – the singer who doesn’t show up until the song’s almost done. (Eno, a pornography connoisseur, also may have suggested Bowie listen to Linda and the Lollipops’ single ‘Theme from Deep Throat’, which has a similar sighing motif.)

‘Sound and Vision’ is the breaking of a dry spell. “The thing that was most exciting about it… I found that without drugs I was still writing very well,” Bowie said in 1993. “Realizing it was possible to survive all that and not become a casualty.” Unlike other Low tracks, where he’d struggled to come up with lyrics, he wrote a long set here, then pared them down. Invoking a muse is older than poetry, and ‘Sound and Vision’ is a humble wish to sit down and wait for the gift. No grand gestures, just a man at a piano, hoping that the notes come, some words appear. He’s wondering aloud if he could ever write a ‘Life on Mars?’ again and isn’t troubled if he can’t. He’s content to have come this far, grateful for what’s left to him. ‘Sound and Vision’ fades out long before one wishes it gone.

Ashes to Ashes by Chris O’Leary is published by Repeater Books in February