Dedicated to the memory of the Residents’ primary composer, Hardy Fox, who passed away aged 73 during the writing of this article

1978 – The Sex Pistols played their final chaotic performance at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom on January 14, whilst Saturday Night Fever fever reached near epidemic proportions in the population at large. In June, the Cramps performed their infamous free concert for patients at the Napa State Mental Hospital. A glance at albums released that year reveals a smattering of visionary recordings nestled amongst more standard late 70s fare. Debut albums by XTC, The Buzzcocks, Magazine, Devo and Public Image Ltd. Second releases from Wire and Throbbing Gristle. Pere Ubu’s The Modern Dance and The Residents’ Not Available both appeared at the end of January, and their subsequent platters both hit the shelves of record stores on November 30. Duck Stab! had appeared as an EP, earlier that year, marking the first instance of commercial success for the West Coast conceptual art collective. Jon Savage’s review of The Residents’ first three releases in the December 31 Edition of Sounds kickstarted interest in the band after several years of perhaps not so unhappily ‘toiling’ in obscurity.

Homer Flynn, The Residents’ spokesman and artistic director, recalls: “Jon Savage came over and he went to a store in the Bay Area – most likely Rather Ripped Records in Berkeley. He was looking for interesting stuff and they were one of the few places at that time that was actually carrying Residents releases. I think he got Meet the Residents, Third Reich & Roll and Fingerprince and wrote reviews of all three at once. Up to that point, The Residents had one room in their warehouse that was nothing but records, because they had to print a thousand at a time, and nobody wanted them [laughs]. But after that, they started flying out the door. That was right when the whole new wave thing was starting to take off. So, Duck Stab! as this little seven inch EP, with little short catchy songs on it, was kind of the right product at the right time. It was right around then that the Cryptic Corporation got involved. I think we sold something like 25,000 fairly quickly, which was a pretty huge number for them.

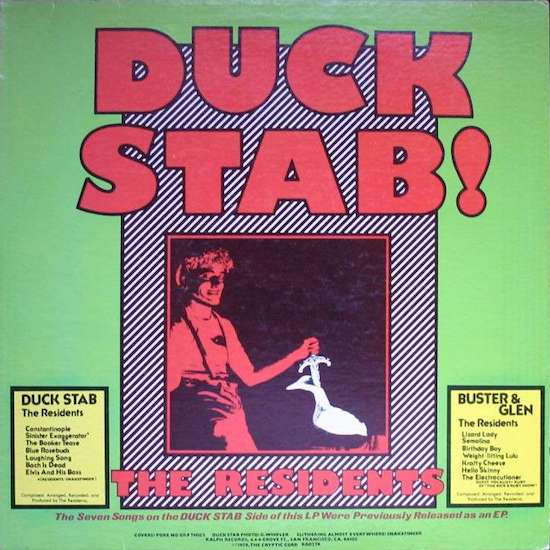

"For The Residents, Duck Stab! was sort of an in-between project. They were working on Eskimo and they knew that it wasn’t going to be ready for some time, but they felt like they wanted to put something out, and so they had these tunes that they were working on, and ultimately they became Duck Stab!. As an almost an off-the-cuff recording, they’ve always been surprised that it has the sort of reputation and longevity that it does. In some ways I think it’s a testament to not taking yourself too seriously. They certainly weren’t, and in a lot of ways, Not Available was made in that same spirit, and that has had a lot of longevity too. They were having fun when they were making those albums. Not that they weren’t having fun when they were making other records, but it just kind of goes to show, sometimes you never really know how something’s going to be accepted by people. I had to put some kind of cover image together, and they had recently done a photo session with Graeme Whifler, the director of a couple of the One-Minute Movies and who also did ‘Hello Skinny’. The album image is a crop of a larger image and it was just something that caught my eye. It was a seven inch cover, so it had to be pretty bold. I showed that to them and they said: ‘Yeah, do it.’ Then ultimately, because the image was so striking, that became the title.”

Due to the unexpected success of the EP, and also because of issues with the poor audio quality of the original recording, the band decided to re-release it as an album with a second side of songs. Often cited as a ‘gateway drug’ to the band, the combined Duck Stab/Buster & Glen featured several of the best tracks they would ever record, including the hauntingly sinister ‘Hello Skinny’. Plying nightmarishly surreal black and white collaged imagery against the eerie clarinet melody and insidious slink of the track’s vocal, Whifler’s accompanying filmic vision ranks amongst the most unforgettable of the band’s history.

Flynn says: “I think it’s a beautiful film, probably Graeme’s best work, at least in terms of what he did for The Residents. There were any number of strange stories around the making of it. One of which was that they hired him just to do music videos and ultimately, he started making, as opposed to a series of music videos promoting Ralph Records acts, a Graeme Whifler film. They had respect for him as a film maker, but that’s not what they felt they were paying him for. So there was a point, which was not too pleasant really, where ultimately the Cryptic Corporation had shut him down. At that point, he sort of got the message and he started working on ‘Hello Skinny’ but he had an office and he would disappear in there for hour after hour after hour. When you see at the very end, where it goes to colour, and you see the skinny character in this strange, surreal set, that’s a scene from the film that he was shooting. There used to be this bar where he hung out a lot and this guy Bridget was supposedly a regular and that’s where Graeme got to know him. He was a very sensitive, completely out there guy, and according to Graeme, he thought he was Bridget Bardot. Once again, I have nothing but Graeme’s word on this [laughs] but I do know, if you look at the film there are all of these shots – still photographs – of Bridget, kind of sitting at a little TV but taken in a bus station. What happened was, Bridget seemed to be having a breakdown and he decided that he had to go home, back to his mother. So, he announced this to Graeme, I think on the day that he was leaving. So those photos, Graeme took in the bus station, just before Bridget got on the bus to go back to his mother.

The album was also the second Residents release to feature the considerable talents of the versatile English guitarist, Philip Charles Lithman, AKA Snakefinger: “Philip was around during the pre-Residents period, and then his visa ran out and he had to leave, and he was gone for several years. He was back in England doing Chilli Willi And The Red Hot Peppers. I believe this was right around the time when he came back. In fact, he’s not on Meet The Residents and he’s not on Reich & Roll, but he is on Fingerprince. Of course, they were happy to have him around again. He had pretty broad tastes. He was way into Frank Zappa And The Mothers, and he was into a lot of really traditional blues and stuff too, so he covered a lot of ground. The Residents really pushed him, in terms of taking risks.”

Likewise, the reciprocal relationship benefitted The Residents hugely too. An unorthodox self-taught southpaw guitarist and violinist with a sense of musical timing as elastic as his Res-supplied nickname would suggest, the ‘wrong note at the right time’ Lithman was the perfect foil for the Residents’ non-linear approach to creating music. Passing away from a heart attack at the tragically young age of 38, Lithman featured on Residents’ albums until the early eighties and released several solo records that have remained criminally overlooked for decades due to their lack of availability. 1979’s Chewing Hides The Sound and 1980’s Greener Postures were recorded and co-written with the Residents, whilst 1982’s Manual Of Errors – his first record with backing band the Vestal Virgins, saw The Residents sharing credits on the tracks ‘Eva’s Warning’ and ‘Bring Back Reality’. Finally re-released by the Austrian label, Klanggalerie, in February of this year, all three albums are are long overdue critical appraisal, and the first two in particular are the closest any other recordings come to inhabiting similar thematic and sonic ground to Duck Stab/Buster & Glen.

Whilst the impromptu and unrestrained spirit behind the album’s inception allowed for the serendipitous formation of its more successful tracks, the chaotic juxtaposition of sometimes nauseating co-components, always a key element in the Residents’ mode of attack, clearly isn’t for everyone. As the Quietus’ own John Doran hilariously wrote in an article entitled Songs Of Discomposure: Quietus Writers Pick Their Most Disturbing Pieces Of Music: “The closest I’ve ever come to having a nervous breakdown primarily because of the intense unpleasantness of a piece of music, was while driving round Bristol in a van, helplessly lost while listening to Duck Stab at full volume. If anxiety has a natural soundtrack, this is it. I know The Residents are important because of art and music and eyeballs and blah, blah, blah but if I had the technological ability I would round up all copies of this record, including the master tapes, nail them to a missile and fire it straight into the heart of the sun. Especially the song ‘Constantinople’. That can properly fuck right off.”

Certainly, ‘Constantinople’ – a kind of monstrously mutated novelty song – rides high in the irritation stakes, but it’s far from being the only timbre and emotional register deployed on the album. The kind of belligerent Dadaesque sense of humour that the Residents espoused years before punk put on its self-consciously rebellious mantle was undoubtedly a key aspect behind their drive to create, however, and is perhaps best explained as a reaction against what the psychedelic era had become by the early 70s. Flynn explains: “The Residents were big fans of the psychedelic era , and in a lot of ways, that was what attracted them to the Bay Area. Ultimately all of those groups either broke up or they found their formula and what really felt initially like a pretty experimental scene, quickly settled down into people doing the same stuff over and over again. I’ve often heard the Residents say, that if those groups had continued to be as experimental and risk taking as they were, as what attracted them to San Francisco, then the Residents might not have ever existed, because they wouldn’t have felt like there was a void to fill. I think there was probably a bit of an aggressive attitude there. You know, in a way a sense of disappointment that the psychedelic era never fulfilled its promise, at least from the Residents’ point of view.”

‘Sinister Exaggerator’ and ‘Hello Skinny’ attain a kind of effortless sublimity in which one can hear the pre-resonance of future musics yet to come. ‘Weight Lifting Lulu’, with its rumbling way-too-deep bass and spectral electronics, and the amusingly titled, ‘Krafty Cheese’, whose deadpan lyrics concerning the relation between plants and people are delivered in what sounds like a near catatonic state, both sound like embryonic experiments in EDM. Both tracks prefigure the Resident’s best foray into this genre, 1984s ‘Safety Is The Cootie Wootie’. The punningly titled ‘Booker Tease’ represents a kind of bridge between the Residents state of mind and the blues background that Lithman had sprung from. ‘Laughing Song’ and ‘Bach Is Dead’ anticipate the kind of concise, perfectly formed ditties they would further explore on the 1980-released Commercial Album. Closing track, ‘The Electrocutioner’ begins at full-throttle, Snakefinger wigging out to the max before settling into a more elegiac tone, with vocals from ‘Ruby’ – supposedly Monica Ganas of ‘The Rick And Ruby Show.’

Pere Ubu’s second album, Dub Housing, released on the same day in 1978, may offer more easily graspable reference points in its amalgamation of Stooges style groove rock, musique concréte and bleak electronic soundscapes, but it remains a similarly singular testament of the triumph of individuality and imagination over commercial similitude. For my money, the best post-punk album of all time, Dub Housing’s uneasy post-industrial vibe is strongly redolent of the queasy, madness-as-method reek of the Residents’ contemporaneous Duck Stab/Buster & Glen. Opening track ‘Navvy’ neatly encapsulates the absurdity of the human condition in two minutes and forty seconds of murky, garage rock that equally evokes the pataphysics of Alfred Jarry, from whose plays Pere Ubu derived their name, and the kind of existential, tragicomic plays of Samuel Beckett in an almost Tex Avery style cartoon-like form:

“I’ve got these arms and legs that flipflop, flipflop

I’ve got these arms that flipflop,

Flip-flip-flip… I have desire

‘Freedom!’

I have desire

Somewhere to go!

(Boy! That sounds swell)"

‘On The Surface’ flirts with standard pop lyrics ("I heard the radio sun/ Made the day like a beach") under Allen Ravenstine’s bizarrely percolating keyboards that at times sound like interference from the very radio the lyrics evoke. ‘Dub Housing’ and ‘Caligari’s Mirror’ offer expressionist takes on the rock format, the former seeping slowly into the listener’s consciousness like a horror film soundtrack and the latter lurching like a dismembered version of the tune to ‘(What To Do With A) Drunken Sailor’. ‘Thriller’ remains a near incomprehensible collage of stuttering sound, whilst ‘I Will Wait’, the album’s shortest track at 1:48, represents Ubu at their wildest, Ravenstine’s stabbing keyboards and Tom Herman’s scrabbling guitar combining to sound like a malformed claw scratching furiously at the walls of its chronological confinement. ‘Drinking Wine Spodyody’ careens like a compressed spring set loose in a padded cell. ‘(Pa) Ubu Dance Party’ combines the twang of surf rock guitar, with a radio voice style sample, stabs of boogie piano and a middle section that artfully falls apart before neatly reforming. ‘Blow Daddy-O’ is a stream of industrial guitar scree presenting itself as if it were a free jazz sax solo, and ‘Codex’ ends the album on a note so melancholic that it pretty much outdoes all other music as an expression of emotional malaise – apart from the funereal dirge of Duck Stab’s ‘Blue Rosebuds’. Dub Housing was most likely recorded with a far more serious degree of intent than Duck Stab, but both recordings equally evoke a kind of creative derangement of the senses that makes them almost impervious to the assimilations usually caused by familiarity, the transferral of ideas from the underground to the mainstream, and to a lesser extent, by the passage of time.

The great American visionary novelist, Steve Erickson, refers to Dub Housing in this sense, in his best novel, Zeroville. A quote equally applicable, perhaps even more so, to Duck Stab/Buster & Glen: “It’s like the first time I heard the second Pere Ubu album and thought it just blew completely, I thought anyone who liked it must be stupid and full of shit – and then for about a year it was practically the only album I listened to. It was the only album that made any sense at all. So why does that happen? The music hasn’t changed. The movie hasn’t changed. It’s still the same exact movie, but it’s like it sets something in motion, some understanding you didn’t know you could understand, it’s like a virus that had to get inside you and take hold and maybe you shrug it off – but when you don’t it kills you in a way, not necessarily in a bad way because maybe it kills something that’s been holding you back because when you hear a really great record or see a really great movie, you feel alive in a way you didn’t before, everything looks different, like what they say when you’re in love or something – though I wouldn’t know – but everything is new and it gets into your dreams.”

The Residents at that time were forging an identity as insular studio experimentalists who would not begin to tour until they took The Mole Show on the road in 1983, whilst Pere Ubu had the appearance of coolly marginal societal misfits, still very much rock & roll but with replete with the electronic sci-fi flourishes of Allen Ravenstine’s EML synth and David Thomas’s wild vocals. Ubu did espouse a theory of obscurity of sorts, in that their initial idea was to record a single and then disappear. Perhaps ironically, both bands still had several notable albums ahead of them, and versions of those groups still tour to this day. In the broader landscape of musical releases though, the baton of prescient experimentalism seemed to to have passed over to the UK by 1979, with the likes of Wire’s 154, The Pop Group’s Y and This Heat’s eponymous ‘Blue And Yellow’ album. Completing a cycle of sheer sonic unorthodoxy first initiated in 1969 and 1970 with Beefheart’s Troutmask Replica and Lick My Decals Off Baby and Zappa’s Uncle Meat, Duck Stab/Buster & Glen and Dub Housing marked the zenith of far-out American experimentalism that could still, however tenuously, be packaged as pop music.

The Duck Stab/Buster & Glen 2CD pREServed Edition is out now on Cherry Red Records. The Residents are on tour early 2019 including UK dates