There are some musicians who are so far ahead of their time that they’re let down by the instruments in front of them. They hear music in their heads that can’t be played yet and they have to wait for technology to catch up. Beethoven was like that. He composed music for the pianos of the future – bigger ones than could cope with the number of notes he was writing. Pianists of his day would have to leave out parts of the score, but it didn’t matter. Beethoven knew how the brain worked; he knew it would be tricked into hearing the missing notes anyway, and also that technology would pull its finger out soon enough, allowing for the piece to be played in full.

Other musicians become so frustrated by the limitations of existing instruments they invent their own ones, as Harry Partch, John Cage and Daphne Oram did. And then there’s George Antheil, an American composer born in 1900, who’s something of a unique case. Entranced as much by technology as he was by music, he wrote a piece in 1924 called Ballet Mécanique that only got performed as he originally intended in 1999, 40 years after he died. He wrote it for, among other instruments, 16 player pianos – self-playing pianos, also called pianolas – which, he soon worked out, were impossible to programme to play together with anything like the precision that MIDI technology now allows.

What was he up to? It’s difficult to say. It’s been speculated that a leading maker of player pianos had invented an electrical system that could synchronise multiple instruments, but it never got made, or it could have been that Antheil’s ambition was blind. However, great showman that he was, he got what he was after when a revised version of the Ballet Mécanique with just one player piano, but plenty of normal ones, and drums, a gong, xylophones, airplane propellers, bells and a siren, was premiered in Paris two years later. It caused a sensation, witnessed by some of the most significant artists living in the French capital at the time, including James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and Man Ray. "From this moment on I knew that, for a time at least, I would be the new darling of Paris," he wrote. "Paris loves you for giving it a good fight, and an artistic scandal does not raise aristocratic lorgnettes."

Antheil’s account of his life is to be taken with a pinch of salt. His autobiography, The Bad Boy Of Music, was a best-seller on publication in 1945, but it can’t be trusted, making him something of a slippery fish in the history of the avant-garde. In fact, he might have been written off as just another art crank and hipster if it wasn’t for the more-classical works he composed after the Second World War, or if he hadn’t run into the Hollywood star Hedy Lamarr in LA in 1940. Lamarr, marketed by her studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as "the most beautiful woman in the world", asked Antheil if he could help put into practice an idea she’d come up with for a radio guidance system that would allow a torpedo to reach its destination undetected, thereby assisting the Allied war effort. They patented their invention and hoped it might be picked up by the US Navy; it wasn’t, but we’ve come to understand how pioneering their work was. It would be 20 years before anyone else designed a similar, complete system for what’s called frequency hopping or spread spectrum – technology now widely used in telecommunications and radionavigation (mobile phones, GPS, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and the rest).

The stock of that story, which begins with Lamarr meeting Antheil at a dinner party and enquiring if his knowledge of the endocrine system might help her increase her breast size, is high. Who isn’t seduced by the idea of the traffic-stopping actress from Austria having a secret life as an inventor and collaborating with an American composer who had caused a scandal in Europe, as indeed she had with one of her pre-Hollywood films? In 1933’s Ecstasy, she went topless and simulated the first-ever on-screen orgasm, resulting in a denouncement from the Pope. He was the ”bad boy of music", she called herself an "enfant terrible", and the covert work they did together during the war has become the source of abject fascination in recent times, overshadowing Antheil’s music and even eclipsing Lamarr’s fame on the screen. I can recommend a 2017 documentary Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story, co-produced by Susan Sarandon and directed by Alexandra Dean, and also a brilliant 2012 book, Hedy’s Folly, by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Richard Rhodes, which informs much of the below.

It’s one thing becoming notorious in Europe, quite another turning a reputation into a tangible career in the States. When they met in August 1940, Lamarr was struggling with being typecast as an exotic, one-dimensional sex siren, although she’d landed a significant, non-starring role in the recently released Boom Town, alongside Clark Gable. Antheil was writing film scores – good ones – but, as his wife Boski said, Hollywood had "corrupted" him in the eyes of the classical music establishment. He couldn’t win. In a blaze of publicity, he’d brought the wild, clanging Ballet Mécanique to New York’s Carnegie Hall in 1927, only to suffer technical problems during the show. It met a "varied response", as The New York Times politely put it; another reviewer managed, "Trying to make a mountain out of an Antheil." He had a torrid time being taken seriously as a composer in 1930s America, forcing a move into film, and also journalism. For Esquire, he flipped his interest in endocrinology into a run of nutty lifestyle columns, ‘She’s No Longer Faithful If…’, and also wrote a series of articles that spectacularly predicted significant events of the coming war, including – to within a week – that Germany would invade Poland. But his revelations were something of a con. His younger brother Henry was working in the American embassy in the Soviet Union and regularly leaked classified State Department cables to Antheil, informing his journalism.

Lamarr, born Hedwig Kiesler in 1914, had made it to America in extraordinary style. Unhappy in a marriage to a powerful Austrian arms manufacturer and dealer, 15 years her senior, she’d fled to London, where she met Louis B. Mayer of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. It was 1937 and he was in town to scoop up European writing and acting talent as war approached. "I saw Ecstasy," he told her. "Never get away with that stuff in Hollywood. A woman’s ass is for her husband, not theatregoers." And yet, as Lamarr recalled, "He was giving close-up inspections from every angle." He offered her six-months’ work at $125 per week, but she’d have to pay her own way to the US. She said no, booked herself onto the same luxury liner that Mayer was taking to New York and – after she’d "become the centre of attention for all the young males" – renegotiated, securing $500/week on a seven-year contract. She was 22 at the time, and barely able to speak English.

The screen adored Hedy Lamarr. Her first American film, 1938’s Algiers, made her an instant Hollywood star, but her interests always extended beyond acting and she had little time for LA’s social scene. "Any girl can look glamourous," she famously said, "all she has to do is stand still and look stupid." Lamarr wasn’t stupid – she had a highly creative mind and with much downtime on set and between films she took to inventing, encouraged by one of her suitors, the business magnate and pilot, Howard Hughes, an inventor himself. They had a brief affair, she said he was terrible in bed, but she admired his "brilliant" brain and he gave her a smaller version of the inventing table and equipment she had at home for use in her trailer at work. Lamarr maintained that she helped with the wing design of the planes he was building by studying the shape of the fastest fish and birds, and he also once offered her the services of two chemists to help her develop a tablet that, when mixed with water, would become a drink like Coca-Cola. "It was a flop," she said, "because I didn’t realise that every state [in the US] had different strengths of water." Better inventions were to come.

In Hedy’s Folly, Richard Rhodes writes: "Hedy invented to challenge and amuse herself and to bring order to a world she thought chaotic." Both Lamarr and Antheil had their own, personal reasons for being devastated by the outbreak of war. Not only was Lamarr Austrian, she was of Jewish descent (a secret she kept from even her children) and she’d lost her beloved father in 1935 to a heart-attack, possibly brought on by the stress of Austrofascism, the authoritarian system of government installed in Austria the year before. Antheil’s brother Henry had moved from Moscow to Finland to work at the US legation there. In June 1940, he was on a commercial flight travelling between Tallin, Estonia and Helsinki that was shot down by the Soviets, making him one of the first American casualties of the war.

Henry’s death, Antheil wrote, "both saddened me and steeled me in the resolution to do whatever I can best do to help my country". Lamarr had married for a second time in 1939 and adopted a boy. The marriage lasted 16 months, but Rhodes believes having a child had fine-tuned her to the horrors happening in Europe, particularly the attacks by German submarines on British ships carrying children to safety in Canada ahead of the Blitz. She decided to invent a remote-controlled, jam-proof torpedo and it was utterly fortuitous that the strange, 5’4" man she’d been introduced to at a dinner party could help. Not only had he once been a munitions inspector, he believed there might also be some answers in his attempts to synchronise player pianos in Paris almost 20 years earlier. According to him, she left the party and wrote her phone number on his car windshield in lipstick – a suggestion that she fancied him, but she liked tall men and there’s nothing to suggest they ever had an affair.

Antheil had ended up in Paris via Berlin and Trenton, New Jersey, where he grew up the bilingual son of German immigrants. His father owned a shoe shop. As a young man, he was obsessed with Russian composers – Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky and Tchaikovsky – and intrigued by the way that they’d found a sound for their nation in the late-19th century. He intended to do the same for America in its new, mechanical age and he sought inspiration in Europe, where modernists like Schoenberg and Stravinsky were rewriting the rulebook for what was possible with music, moving away from tonality and experimenting with a different, rhythmic feel.

A talented and powerful pianist with a percussive style, Antheil initially went to Europe to tour as a concert pianist. He stayed for a decade, sponsored by the generous daughter of a wealthy newspaper tycoon (she eventually tired of him and pulled her support). He fluked a meeting with Stravinsky in Berlin, fell out with him in Paris, but nonetheless found himself in the midst of an artistic revolution centred around the Shakespeare & Company bookstore on the Left Bank. It was run by a visionary American, Sylvia Beach, who in 1922 published James Joyce’s controversial novel Ulysses. Antheil didn’t just hang out there, hobnobbing with Ezra Pound, Erik Satie, Picasso, Jean Cocteau and countless other luminaries, he lived upstairs with his Hungarian wife, Boski, who he’d met in Berlin.

Antheil made his name at a 1923 concert of pre-Ballet Mécanique works. There was a riot, but it was staged by the filmmaker Marcel L’Herbier, who needed the footage for an experimental short he was directing called L’inhumaine. Antheil may not have known of L’Herbier’s plan, but he certainly used the chaos to his advantage. Ten years earlier, the premiere of Stravinsky’s The Rite Of Spring had created similar bedlam in exactly the same theatre – a parallel that Antheil was far too shrewd to miss. "I was famous overnight," he said, just as Stravinsky had become in 1913.

At the concert, Antheil played his Airplane sonata, Sonata Sauvage, Death Of Machines and Mechanisms – all clues to the hard, post-Romantic American sound he was aiming for. Mechanisms was written for a player piano, but just one. Soon after, he began work on Ballet Mécanique, originally commissioned the soundtrack for a Dadaist art film made by Fernand Léger, Dudley Murphy and Man Ray, although the film premiered without the music, which took on a life on its own (it’s twice as long). "Scored for countless numbers of player pianos," he wrote about the work. "All percussive. Like machines. All efficiency. NO LOVE. Written without sympathy. Written as cold as an army operates. Revolutionary as nothing has been revolutionary."

Even today, player pianos are a marvel to witness in operation. A paper roll with holes punched into it, corresponding to notes, is inserted into the top of the piano, like a cassette into a tape player. The keys play alone because of a complex pneumatic-mechanical system within the piano, set off by pumping a foot pedal, which is the only action a human being needs to perform. It you can’t see the player’s hands, it seems like they’re playing a fiendishly difficult work by Rachmaninov or Ravel, and it’s no wonder they became popular sources of entertainment in people’s homes before radio and the phonograph rendered them redundant in the 1920s, just as Antheil was working on Ballet Mécanique.

But for Antheil, the player piano was much more than a technological gimmick to amuse the middle classes in Europe and America, who bought more of them in 1919 than actual pianos. If he could have pulled it off, the spectacle of 16 of them playing four different parts together, along with bells, airplane propellers and whatnot, would of course have been a sight to behold – and made an enormous noise – but it was what was possible with the paper roll that truly sparked his imagination. As Rhodes has it, the player-player roll was "an early system of digital control, like the punched-card control system of the early-19th century Jacquard loom from which it ultimately derived. Antheil did not forget its usefulness."

The problem Hedy Lamarr decided to solve was thus: how can a torpedo fired from an Allied ship or submarine reach, and consequently destroy, a German ship or submarine with accuracy and without being detected? As far as accuracy is concerned, radio control technology was already in development. If the firing ship or submarine is in contact with the torpedo via radio and it swings off course, its trajectory can easily be changed. But what if the enemy could locate the radio frequency being used to guide their torpedo? They could jam it, removing the threat. So Lamarr imagined a system where the frequency would hop around constantly between different channels in a sequence known to both transmitter (ship or submarine) and receiver (torpedo), making it impossible to detect.

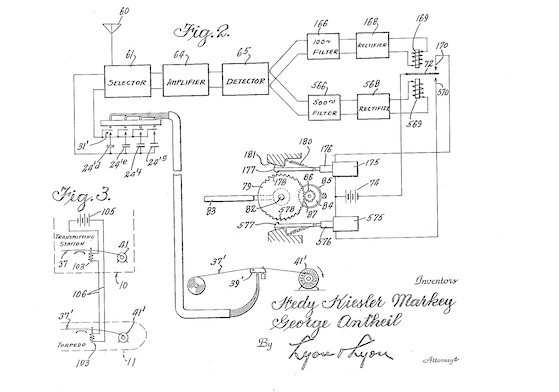

As an idea, it was simple, elegant and profound. Antheil’s contribution was to suggest how to physically put frequency hopping into practice. As Rhodes writes: "Antheil had faced a similar control problem when he attempted to synchronise player pianos, and the mechanism he now proposed for his and Hedy’s invention was similar: using matching player-piano-like rolls of paper in transmitter and receiver with slots cut into the paper to encode the changes in frequency. As the slots rolled over a control head, they would actuate a vacuum mechanism similar to the mechanism in a player piano, except that instead of the operation culminating in a pushrod moving the piano action, it would culminate in pushrods closing a series of switches."

The other problem they faced was how to start the rolls in the transmitter and receiver at the same time and, as Antheil said, "in proper phase relation with each other, so that corresponding perforations in the two record strips will move over their associated control heads at the same time". With electronics (and possibly some external advice), they cracked that issue too, and managed in 1942 to secure a patent for their invention, which they named ‘Secret Communication System’. It sounds absurd – getting two piano rolls to have an undetectable conversation with each other, with one of them being inside a moving torpedo – but it was inspired, and as a system for secure radiocommunications it was decades ahead of its time.

Debate over their invention still rages, however. Did Lamarr really come up with the concept of frequency hopping, or did she nick it from her first husband, Fritz Mandl, the arms manufacturer? Has Antheil’s role been played down, beaten into submission because the story of "the most beautiful woman in the world" having a flash of extraordinary genius has higher currency as a tale? There’s misogyny in both of those accusations. Antheil was hardly the kind of man to let anyone else steal his thunder and he was always careful to attribute the idea to Lamarr (as indeed she always said "the implementation part came from George"). And while it can’t be proven that the seed of an idea wasn’t smuggled out of her husband’s chest of secrets, as Rhodes says in the Bombshell film: "The record is very clear: the Germans had not come across the idea that would be Hedy’s single contribution."

"I know what I did," she said in 1991. "I don’t care what other people say about me." And, at any rate, Lamarr and Antheil’s ‘Secret Communication System’ materialised in nothing. Despite lobbying, the Navy turned their invention down, leading to Antheil to write a wry letter to his friend, the diplomat Bill Bullitt. "They said that the mechanism we proposed was ‘too bulky to be incorporated in the average torpedo’… Our fundamental two mechanisms – both being completely, or semi-electrical – can be made so small THAT THEY CAN BE FITTED INSIDE DOLLAR WATCHES!" He also explained where he thought they’d made their key mistake – in mentioning that part of the mechanism worked not unlike a player piano. "The reverend and brass-hatted gentleman in Washington who examined our invention read no further than the words ‘player piano’. ‘My God!’ I can see [them] saying. ‘We can’t put a player piano into a torpedo!’"

Lamarr wanted to continue work on their invention, but Antheil was done. Fourteen years older than Lamarr and still smarting from the kicking Ballet Mécanique had been given when he took it to Carnegie Hall in 1927, he had his reputation as a composer to win back. "I changed my musical style radically in 1927," he said, "deciding upon a lyric style and the investigation of operatic possibilities." Throughout the 30s his new works fell on deaf ears and even as late as 1945 he was accused of being – of all things – a musical square. "He has turned into such a conservative composer that he has been compared with Mozart and Brahms," sniffed The New Yorker. But Antheil was nothing if not determined. By 1947, he was among the four most-performed American composers, alongside Samuel Barber, Aaron Copland and George Gershwin, and he enjoyed a musical Indian summer that lasted until his death in 1959, the same year that the ‘Secret Communication System’ patent expired.

Lamarr’s post-war story is an epic in itself. She had her biggest hit of all in 1949, playing the lead in Cecil B. DeMille’s biblical drama Samson And Delilah, went into film production – unheard of at the time for a front-of-camera female star – lost money, married four more times (making six in total), became an American citizen in 1953, built a villa in Aspen, Colorado, turning it into the famous ski resort that we know today, and made her last film in 1958, The Female Animal. It’s thought that she may have struggled with prescription drug addiction in the 1960s. She was arrested twice for shoplifting, once in the 60s and again in the 90s, suffered many botched cosmetic surgery operations, and became, effectively, a recluse living in Florida. But she did win recognition for her invention before she died in 2000, aged 85. A landmark 1991 interview with Forbes introduced the other, unknown side of Hedy Lamarr to a new generation of techies keen to know, and in 1997 she was honoured, along with Antheil, by the Electric Frontier Foundation, who gave the odd couple their annual ‘Pioneer Award’. Lamarr’s response on hearing the news? "It’s about time."