For years, I loved Dire Straits. For years after, I hated them, or professed to, and thought I had loved them only because I knew no better. When you consider that their productive years (1978–1985; they released a final outlier of an album, On Every Street, in 1991) coincided with one of pop music’s most thrilling and inventive eras, much of which I missed while it was going on, this wasn’t an unreasonable thing to think. But it was the wrong thing to think. Wrong as in, mistaken. Over time I came to realise I had loved them because there was plenty there to love.

And plenty to hate. Or at least to be put off by. That last album came out just when I was starting to write about music, and I recall colleagues of mine laying into them thus (I paraphrase from memory): “Dire Straits – has any band ever been so aptly named? It couldn’t suit them better if they were called We’re So Boring Even Our Farts Are Odourless.” By that point, it seemed fair comment. On Every Street was indeed sawdust-dull. Its predecessor, Brothers In Arms (1985), was the album whose success had ensured the compact disc would become a viable commercial format. In 1991 CDs were still considered middlebrow, middle-class, the preserve of men with high-street suits and mid-range company cars, all shiny surface and no substance or depth (the suits, the men, and the format); somehow, in short, inauthentic. And Dire Straits were the emblematic CD band, the group nonpareil for those Ford Mondeo drivers.

All of which was, and is, snobbery and bullshit. The part about who made up Dire Straits’ audience demographic may have some truth to it, but so what? There is no such thing as an authentic or an inauthentic pop act, or audience, or format. All pop music is by its existence synthetic. Some of it celebrates this, some is at pains to conceal it, and either is fine. Because the game has no rules. Because it isn’t a game. Because if it were it would be something altogether lesser than the marvellous thing it is.

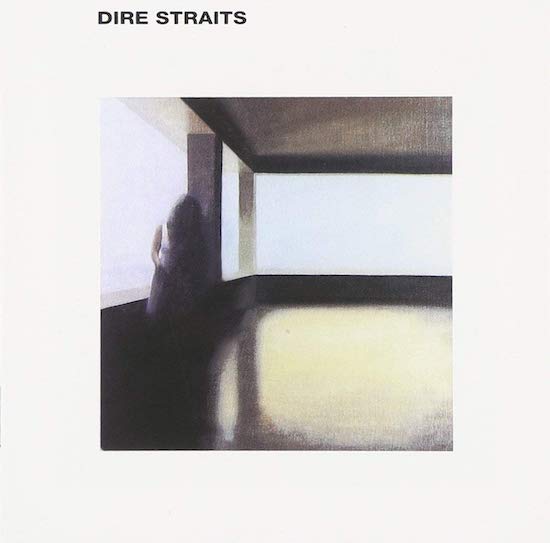

Which is not to say that calculation or cynicism are irrelevant. They can make things dreary or plain unbearable. They certainly made Brothers In Arms, the first Dire Straits album I heard upon its initial release, unbearable to me. Because it is the prism through which the rest of their career is seen backwards, it may be hard to credit now that it felt as if Dire Straits had sold out; but it felt as if Dire Straits had sold out. And to understand why means going back to their first, self-titled album, in 1978.

Dire Straits are one of those bands whose career reminds you that the narrative of pop history is bunk. Yes, punk and post punk happened, and they mattered, a lot. But narratives tend to allow for only thing at a time. Whereas in reality everything happens at once, and it’s only when the waters recede and you see where they deposited their cargoes that you understand how many currents there were and which way they were flowing. Which is how, in 1978, with so much British and American music surging in experimental directions both in and out of the charts, a band whose least trad aspect was their connection to a pub-rock group called Brewers Droop, a band who at their very edgiest strongly evoked the mid-1970s work of Eric Clapton and JJ Cale – and most of all, Eric Clapton covering JJ Cale; his version of ‘Cocaine’ is all but a blueprint for much of Dire Straits – could become a breakout success. (Incongruously, they also supported Talking Heads on the latter’s 1978 UK tour, because that’s the way music history actually occurs.)

Taken in isolation, Dire Straits is not a great record, although it’s a record with great things on it – not least their first single, ‘Sultans Of Swing’, the band’s biggest international hit until ‘Money For Nothing’ topped the US charts seven years later, and a stone cold banger that ought to get played out a lot more than it does. What is remarkable about their debut is the way it sets out Dire Straits’ stall so completely from the off. They are a band who are much better appreciated over their full body of work than on any one album, and Dire Straits contains the bulk of the elements that they would develop over the coming years.

Dire Straits shouldn’t be mistaken for a solo act and a backing group. They were a band, and they played like one; but in every essential aspect, they were Mark Knopfler’s band. He wrote the songs, he sang them – sort of; almost – and it was his rippling, plangent, finger-picking virtuosity on the guitar that gave them their USP: a high, thin lead style that still sets some listeners’ teeth on edge like nothing else, while others marvel at it. I spent countless teenage hours trying to emulate it, having no clue he didn’t use a flat pick, and thus became moderately but quite differently handy in that accidental way that tended to happen before the instant availability of all information. (I sometimes wonder if that’s part of what has slowed down pop evolution, by reducing the opportunities for random mutation, but that’s a question for another day.)

Clapton and Cale aside, the most obvious influence on Knopfler was Bob Dylan. His slumbrous, mumbling, half-spoken vocal style, with consonants sliding off it like pebbles down a clif, and vowels disappearing into nowhere, recalls Dylan so strongly that, when he was recruited by the latter to play on the undervalued album Slow Train Coming (1979), the early Dire Straits records must have sounded like job applications. But Knopfler wasn’t an acolyte. He sounded like Dylan; he didn’t write like him. He didn’t try to.

As a writer, Knopfler swiftly showed himself to be one of Britain’s best exponents of what in America is known as “heartland rock”, and to his great credit, he made it feel distinctly of its own home – American in sound, certainly, but British in feeling. When it comes to rock & roll, Britain doesn’t have America’s mythic properties; but if, as I did when I first heard Dire Straits, you live on the equator, London or Newcastle are no less exotic to you than, say, the Rust Belt. There is no implicit cringe in Knopfler’s best songs; no sense that his is an inferior subject. Rightly so. A song such as Dire Straits’ pearl of an opener, ‘Down To The Waterline’, capturing the excitement of a youthful tryst on the Tyne, is every bit as evocative in its combination of social realism and romanticism as its transatlantic equivalents: It has no chorus, and each of its verses ends on a couplet of satisfying simplicity: “A foghorn blowing out wild and cold/ A policeman shines a light upon my shoulder… No money in our jackets and our jeans are torn/ Your hands are cold but your lips are warm.”

Across the first two Dire Straits albums – the second, Communiqué, is very much a retread of the first, and between the two of them you could just about assemble one really good LP – these are the songs that cut through; the songs of life and place observed, not imagined. ‘Sultans Of Swing’; ‘Down To The Waterline’; ‘Southbound Again’, with its themes of frustration and displacement (“Every single time I roll across the rolling River Tyne/ I get the same old feeling”); the delicious, leisurely, lascivious stroll through a ‘Wild West End’ now largely vanished from London; ‘Single-Handed Sailor’, that breezy, lovely tribute to both Sir Francis Chichester and the Greenwich riverfront where his boat the Gypsy Moth IV was then displayed. The more lacklustre tunes you could shed in this exercise tend to be leaden retreads of the me-man-you-woman variety: ‘Water Of Love’, ‘Angel Of Mercy’, ‘Follow Me Home’. (I do rather like ‘Lady Writer’, which is sprightly, and feels like a portrait of a real person, and is also such a blatant knock-off of ‘Sultans Of Swing’ that it’s almost endearing.)

Dire Straits’ third album followed only a year after their second, but it was as ambitious a leap forward as Communiqué had been a modest treading of water. Making Movies (1980) is my favourite record of theirs by some distance, but it was only on a recent revisit that I worked out why. It is, simply enough, a British Bruce Springsteen album – and a marvellous one, at that. It’s no accident, either. Knopfler asked Jimmy Iovine, then best known as an engineer for Springsteen and producer for Tom Petty and Patti Smith, to produce the album; Iovine in turn brought in Roy Bittan of The E Street Band. Remarkably for a Dire Straits album, it is Bittan’s rolling, expansive piano, rather than Knopfler’s guitar, that is its defining sound. The meshing of the two is glorious. It is unimaginable that Dire Straits could have made this album but for Springsteen; equally, nobody else, not even Springsteen, could have made it, either. It is one of those curious and uncommon works that is both an hommage and a work of unique character.

Its opening track, ‘Tunnel Of Love’, would be the first thing I would play to anyone I wanted to persuade of Dire Straits’ merits, on the basis that if they don’t like that, they won’t like any of the things that are good about them. It’s a perfect song about the yearning for the sudden thrills of youth; the most wonderful, redolent, fond, gritty, tender recollection of passing fancy, rather as if Knopfler had revisited ‘Down To The Waterline’ armed with all the knowledge and confidence two years of success and maturing creativity had brought him. His rose-tinted tour of the North-East’s pleasure grounds is brimming with life and joy, and the parallels he draws between them and their equivalents in America’s north-eastern seaboard, so often invoked by Springsteen, give away from the off a connection he evidently has no wish to hide.

Making Movies is such a rich album, such a beautifully realised one, drawing in references from across Knopfler’s musical schooling, stretching out with such ease and assurance across ‘Romeo and Juliet’ (a more bitter than sweet account of his failed affair with fellow musician Holly Vincent that would become one of his band’s classic tracks), the soft-footed, atmospheric ‘Skateaway’ (one of Knopfler’s motifs is girls he’s watched in the street, and it sometimes veers towards the creepy; but this, like an upgraded version of his earlier song ‘Portobello Belle’, is a work of admiration for its subject’s poise and self-sufficiency rather than a musical ogle), and all through the slighter but still rewarding second half, that it is something of a shock when it crashes into its final track, ‘Les Boys’, like a train going through the buffers. This oompah cabaret number about a crap gay act in a Munich bar is so notable an example of “‘Jazz Police’ syndrome” – an unaccountably dreadful track on an otherwise excellent album – that it seems a little unfair on Leonard Cohen not to have called the phenomenon after Knopfler’s song instead. It also encapsulates a faintly nasty streak in Knopfler’s writing; nothing you could point to with certainty – both this and the reference in ‘Money for Nothing’ to “The little faggot with the earring and make-up” fall under what I would call The Narrative Exemption. That is, writing in another voice, telling a story from another viewpoint. But you know when something feels a bit off, and this stuff does. As a footnote, I wonder if Knopfler ever noticed the similarity between the reactionary scorn for rock musicians that he satirises in ‘Money For Nothing’, and his own evidently sincere contempt towards avant-garde art in a song from Dire Straits, ‘In the Gallery’.

Two years later came Love over Gold. We all have records we blow hot and cold on, and this is one of mine. It’s far the most ambitious thing Knopfler and his band ever attempted, yet it’s also one of the most derivative. The epic first track, ‘Telegraph Road’, isn’t Knopfler doing Springsteen as himself, the way ‘Tunnel of Love’ was. It’s Knopfler doing Springsteen as Springsteen, right down to the subject matter of blue-collar American life in a tanking economy. There are times it impresses and thrills me, times when it seems little more than a fan letter. Likewise, at the other end of the album, ‘It Never Rains’ feels less like something that was inspired by Dylan’s revenge songs, more an attempt to add to their number while he wasn’t looking. I have a soft spot for ‘Industrial Disease’, which I often think of as a sibling to Pink Floyd’s ‘Not Now John’, but with Roger Waters’ typically clodhopping “Wake up sheeple!” sneers at the working classes supplanted with a much more wry approach. (Waters could almost be the protest singer at Speaker’s Corner whose lyrics Knopfler’s narrator repeats: “They’re pointing out the enemy to keep you deaf and blind/They want to sap your energy, incarcerate your mind/They give you ‘Rule Brittania’, gassy beer, page three/Two weeks in España and Sunday striptease . . .”) Love over Gold’s enduring appeal for me lies in the sombre, hushed ‘Private Investigations’, with its exquisite Spanish guitar lines, its powerful lyrical concision and ambiguity, and its muttered descent into the shabby and tawdry depths of human behaviour. (It’s astonishing to think now that it reached number 2 in the UK charts.) The final lines might just as easily describe one of the cases the investigator takes on, or his own existence:

Scarred for life

No compensation

Private investigations

It was all this, then, that Brothers in Arms seemed simply to wipe off the slate, replacing it with a sound so slick and streamlined that all the variety and nuance of the first four albums vanished, and only the inspidity remained. It’s not always a bad thing for an act to make a grab at the brass ring in this way: Springsteen himself, and David Bowie, and ZZ Top, to pick three near-contemporaneous examples, all made cracking albums in doing so. Born in the USA, Let’s Dance and Eliminator had all come out in the preceding years. Perhaps it was seeing how a big act could thus become a giant one that gave Dire Straits the idea. And Brothers in Arms isn’t as bad as I remember it. But then, it hardly could be. With the exception of the godawful ‘Walk of Life’, which causes me something close to physical anguish, it slides by harmlessly enough, with moments of poignancy. But harmlessness is a very low bar for a band who, at their finest, brought substance and sensitivity to what they did. There’s a great Dire Straits best-of to be compiled, but it’s not, to my knowledge, any of those that already have been.