Kate Bush has never been fond of the way The Red Shoes sounds. In 2011, when explaining why she’d chosen to rework seven of its songs for Director’s Cut, she repeatedly blamed the “edgy” production she felt robbed it of its warmth and depth. She told the BBC she regretted abandoning analogue equipment in favour of digital techniques. She admitted to Mojo that it sounded like she’d been “trying too hard”. And she repeated the same criticisms to Pitchfork, albeit with a crumb of belated affection. “It was interesting actually hearing the whole of Red Shoes,” she said. “It actually wasn’t as bad as I thought.”

That might sound like damning with faint praise, but it’s pretty lavish compared to the dinging it often gets online. It’s routinely dismissed as mundane and conventional, and rare is the rank-the-Kate-Bush albums list that doesn’t have it near the bottom. Even as someone who loves The Red Shoes, it’s not had to understand these gripes; putting the production problems to one side, it’s almost certainly the most normal of all her records, both in sound and sentiment. Bush started work on the LP with an eye on performing live for the first time since 1979’s exhausting The Tour Of Life, which meant less of her usual studio-made magic and a more organic, live-sounding style easier to replicate on stage. The tour never materialised, but the stripped-down approach remained: the opening ‘Rubberband Girl’, with its loose, bouncy energy, is as breezy as Bush’s newfound go-with-the-flow philosophy. “If I could learn to give like a rubber band, I’d be back on my feet,” she sings, happy to bend rather than break.

The problem is that The Red Shoes feels much more tethered to real life, to Bush’s own life, which isn’t what people typically want from Kate Bush at all: her genius lies in dreaming up wonderfully peculiar stories, the kind few could ever imagine, and spinning them into brilliantly captivating pop songs despite their inherent strangeness. Her narrators have included a foetus frightened of radiation sickness, a small boy remembering his father’s secret rain-making machine, a suspicious wife catfishing her husband, a jittery bank robber plagued by nerves. Even 1989’s The Sensual World, which shifted her into more mature, less fantastical territory, has one protagonist who develops an unhealthy relationship with their computer, and another who accidentally dances with Hitler.

A song like ‘And So Is Love’, on the other hand, feels more confessional, more everyday, more ordinary. Its smooth, tasteful art-rock details the messy denouement between two unhappy lovers who realise they have to let go while they still can: it’s raw, painful and, you’d imagine, grounded in the real-life ending of Bush’s romantic relationship with Del Palmer (who she continued to work with). Her solemn vocal is a fine match for the mournful strings of Eric Clapton’s guitar and the stately organ of Procol Harum’s Gary Brooker, but you can’t help but feel as if she’s taken a step into their slightly more colourless, conventional world; that she’s had to smooth off her edges to fit with them, rather than the other way round; that it’s just a little bit too commonplace.

But the way people chafe at the prospect of Bush being more relatable can, I think, be a bit suspect (it certainly wasn’t uncommon for critics to suggest her creativity had been blunted by personal contentment and motherhood on 2005’s Aerial, as if writing about domestic life and writing interesting songs are somehow mutually exclusive). Plenty of people have described her as “mad” – Bush herself among them – but it does her a disservice: it makes her sound like an eccentric ingenue not in control of her own talent, whereas the truth is she fought hard for autonomy after she was strong-armed into releasing Lionheart so soon after The Kick Inside. It can also be a creatively stifling label, too: to fetishise Bush as the madwoman in pop’s attic may feel like a neat way of celebrating those theatrical, eccentric flights of fancy, but perhaps it doesn’t leave her much room to come downstairs.

The most powerful moments on The Red Shoes are its most intimate and personal. ‘Moments Of Pleasure’ starts with piano so soft and gentle it feels like it might vanish if you breathe too hard, before it’s swept up in Michael Kamen’s elegantly soul-stirring orchestral arrangement. Bush’s voice goes through a similar transformation, too, growing from a gentle flutter to something stronger, which makes her heartfelt cry on the chorus sound like a defiant refusal to be swallowed by grief: “Just being alive/ It can really hurt/ And these moments/ Are a gift from time.” Its outro remembers some of Bush’s lost friends – including guitarist Alan Murphy, producer John Barrett and lighting director Bill Duffield – and plays out like the closing credits of an old-fashioned weepy. Even more devastating is an old conversation she recalls with her mother, Hannah, who was ill while Bush was writing the song and who passed away before the album was released. “I can hear my mother saying ‘Every old sock needs an old shoe,’” remembers Bush warmly. “Isn’t that a great saying?” It is, even if it sticks a tennis ball-sized lump in your throat.

There’s emotional heft on ‘Top Of The City’, too, which takes a similar premise to ‘And So Is Love’ but adds higher stakes: Bush sits up in the skies, looking down at the lonely city below and hoping to find an answer. “I don’t know if I’m closer to Heaven, but it looks like Hell down there,” she declares, caught between exhilaration, melancholy and desperation: the moments of quiet calm are both beautiful and unsettling, with eerie pockets of silence hanging between delicate piano notes, until there’s a big, dramatic burst of violins and celestial backing vocals. “I don’t know if you’ll love me for it,” she yells wildly, forcing the moment to its crisis. “But I don’t think we should suffer for this/ There’s just one thing we can do about it.”

As heart-rending as those two tracks are, the simplicity of The Red Shoes can be endearingly playful. In 2o11, Bush called the happy-go-lucky ‘Rubberband Girl’, with its twanging guitars and parping trombones and trumpets, a “silly pop song”: she’s right, and the reason it spreads so much contagious joy is because you can tell she and her band are having such a ball, especially when she wails “rub-a-dub-dub” and makes her voice wobble and vibrate like a boinging bungee cord. The calypso-flavoured ‘Eat The Music’, which features Malagasy musician Justin Vali on the valiha and the kabosy, is equally fun, as Bush puts a new spin on the idea of getting fruity with a lover. “Let’s split him open, like a pomegranate,” she chants. “Insides out/ All is revealed.” “I wanted it to feel joyous and sunny, both qualities are rife in Justin as a person,” said Bush, who met Vali through her brother Paddy. “I just had to provide the fruit.”

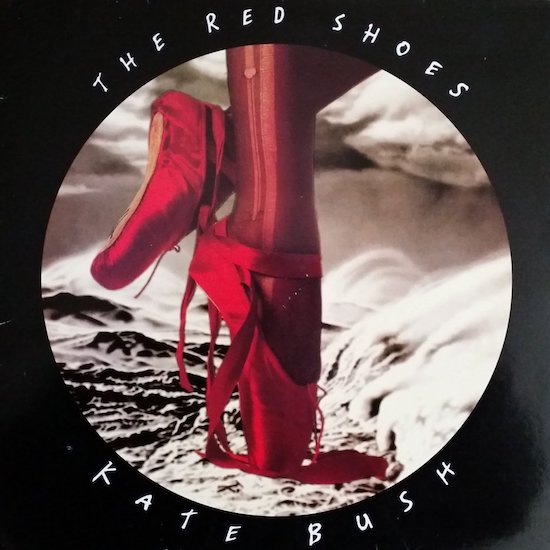

Hearing her equate emotional intimacy with scoffing mangoes and plums might suggest that The Red Shoes still has plenty of idiosyncrasies. There’s certainly something quintessentially Bushian about some of its songs, including the title cut, which soundtracks the fate of a girl who puts on a pair of red leather ballet shoes and dances a frantic Irish jig: it combines her fondness for Celtic sounds, old stories and classic film (The Red Shoes was written by Hans Christian Andersen and later adapted into a 1948 film directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, the former of whom Bush salutes on ‘Moments Of Pleasure’), and her shrill, possessed vocal makes it sound like a feverish fairytale. The steamy ‘The Song Of Solomon’, meanwhile, mixes a literary text and desire in the same way that ‘The Sensual World’ let Ulysses’ Molly Boom step off the page and experience physical pleasure. This time, there was no-one stopping Bush lifting lines from her chosen book, the Hebrew Bible, although the erotic charge of the chorus is all hers: “Don’t want your bullshit, yeah/ Just want your sexuality.”

And if Bush has dabbled with the gothic and supernatural ever since ‘Wuthering Heights’, there’s more magick on the moody, witch-rock of ‘Lily’, a tribute to her friend and spiritual healer, Lily Cornford. “I said ‘Lily, oh Lily, I’m so afraid,’” trembles Bush. “I fear I am walking in the vale of darkness.” She banishes the evil spirits with fire and the help of four angels, although Gabriel, Raphael, Michael and Uriel couldn’t save The Line, The Cross And The Curve, the Bush-directed film-meets-visual-album which included videos for ‘Lily’ and five of the LP’s other songs. Inspired by Powell’s original movie, the singer is tricked by Miranda Richardson into wearing the cursed ballet slippers, and must free herself from the curse under the tutelage of Lindsay Kemp. It was, Bush later claimed, a “load of old bollocks”.

It’s easy enough to find the common thread running through The Red Shoes: time and time again she returns to being brave, to being strong, to being open, to having to decide between holding on or letting go, and still trusting you’ll come out OK on the other side. There is, admittedly, less of a sonic coherence, especially in its latter stages. ‘Constellation Of The Heart’ is a colourful swirl of funky guitars, organs and saxophone, while ‘Big Stripey Lie’ is built upon Nigel Kennedy’s gorgeous violin but is undercut by bitty guitars and discordant squiggles of noise, its scorched beauty hinting at violent chaos as Bush frets: “Oh my god, it’s a jungle in here.”

That’s then followed by the absurdity of ‘Why Should I Love You?’ Bush had originally asked Prince to record backing vocals for the track, but he decided to take it apart and add guitars, keyboards and brass, too. Conventional wisdom is that great collaborations are the result of a shared vision, but ‘Why Should I Love You?’ is great even though there’s absolutely no shared vision whatsoever: for the first 60-odd seconds it’s built around Bush’s hushed vocal, until Prince’s huge rush of ecstatic, kaleidoscopic sound steamrolls everything in its path. It’s less the meeting of two minds and more the smashing together of two completely different styles, the most special of cut-and-shunt hybrids. (And somewhere, among all the hullabaloo, you’ll also hear backing vocals from Lenny Henry).

There’s another cameo on the closing song, the fantastically histrionic breakup ballad ‘You’re The One’, on which Jeff Beck’s dizzying, drawn-out guitar solo pushes Bush to an exhausting catharsis. Like so much of The Red Shoes, it finds her preparing to leave a lover to save herself, although this time she’s less bullish, more prone to tying herself in knots. “I’m going to stay with my friend/ Mmm, yes, he’s very good-looking,” she admits. “The only trouble is, he’s not you.” By the song’s end, she’s so frazzled by frustration and anguish that she lets rip a larynx-tearing shriek: “Just forget it, alright!” Bush, who had spoken of feeling emotionally burnt-out years before the album was released, was ready to withdraw, too: she vanished for 12 years until Aerial, and then went on hiatus for another six before returning with Director’s Cut. “I think there’s always a long, lingering dissatisfaction with everything I’ve done,” she said in 2011, glad to have the chance to right some of the wrongs that had been bothering her for 20-odd years. For me, though, the original album has always been enough: it might have its flaws, and there might be a handsome alternative, but just like Bush on ‘You’re The One’, I still want to keep going back.