When Lynn Hirschberg profiled grunge’s king and queen for Vanity Fair in 1992, she kept circling back to one idea: that Courtney Love, hellbent on boosting her star, had set out to snare a big celebrity. “She definitely relishes her position as Mrs. Kurt Cobain,” she declared. “It was one of her goals, not something she left up to fate.” Instead, Hirschberg suggested, Love planned, she plotted, she pestered and pursued. She even prayed. “Courtney chanted for the coolest guy in rock ‘n’ roll – which, to her mind, was Kurt – to be her boyfriend,” claimed a source, setting Love up as a scheming witch reciting an incantation.

By detailing Love’s slumped acting career, her initial ambivalence towards punk and her hunger for fame, Hirschberg fleshed out a caricature that dogged her for decades: the conniving, bandwagon-jumping opportunist. The music press could be equally unflattering. A month before the Vanity Fair piece, NME’s on-the-road feature with Nirvana labelled her a “Grade-A pain in the arse”. Love would argue that her marriage, far from being a career boon, had been detrimental: people saw her as wife first, artist second, or cast her as grunge’s shrewish Lady Macbeth. They punished her because she was a woman who’d gotten what she wanted, and as she told Caitlin Moran, they thought the worst of her: “‘She’s just a money-grabber gold-digger bitch whore slut.’” Some refused to budge from that position, ignoring the sludgy violent shock of Hole’s 1991 debut Pretty On The Inside, or crediting the perfect alchemy of pain, anger and hurricane-force power on 1994’s Live Through This to her husband. After Cobain’s suicide they doubled down, blaming her for being a destructive force or, risibly, the mastermind of a murder conspiracy.

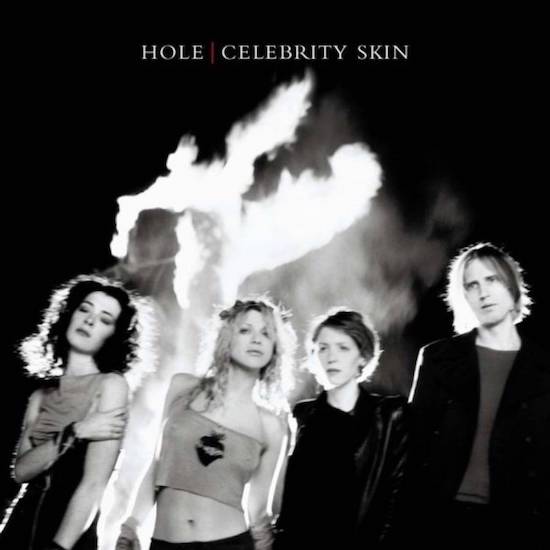

Hole have sounded angrier, rawer and more vital than they do on 1998’s Celebrity Skin, and they’ve made albums both more incendiary and more important. But there’s something about its sleek shininess that feels magnificently defiant, like someone raising a middle finger clad in swanky velvet gloves. For years, dullards had insisted Love was a fame-chasing phoney. Why bother proving them wrong when you could have so much more fun seemingly proving them right? Celebrity Skin is so unashamedly populist it feels like an act of gleeful provocation. It’s selling out and sacrilege as insurrection. It’s the band who released ‘Retard Girl’ and ‘Teenage Whore’ making an album dominated by what Love called the “internal AM pop radio in my heart”. It’s mainstream gloss weaponised into one glorious fuck-you. When Melody Maker’s Everett True told Love of his dislike for the album’s smooth AOR influences, Love was unrepentant. “I’m not going to be held back by bad punk training,” she insisted.

And so Celebrity Skin’s sheen is so hopped up on power and polish it’s practically begging would-be critics to take a pop. The title track is a brilliantly trashy blitz of noise, its riffs filthy with grime and glitter, a punk stomp turned into a sordid burlesque. But much of its brilliance lies in how knowing it is; the way Love hams it up like a pro-wrestling heel, winking hard and pushing her enemies’ buttons. There’s something deliciously goading about Love, so often accused of being a callous, fame-chasing horror (and now a Versace-wearing film star after 1996’s The People vs Larry Flynt), singing about soiled glamour and fame’s toxic fakery. Every pose she strikes – the desperate wannabe, the bitter star, the leading lady who “obliterated everything she kissed” – feels like a grotesque reflection of every wicked caricature she’s been cast as, as if she’s performing inside a funfair house of mirrors. In the opening lines, sneered over that Earth-splintering crunch of guitars, she sings as a monster-made-flesh: “Oh make me over, I’m all I wanna be/ A walking study in demonology.” And later, on the dangerously sweet post-chorus, she crows like Norma Desmond reborn as one of the Furies: “I’m glad I came here with your pound of flesh.”

Coveting mainstream success had been a blasphemous idea in Seattle’s underground, but Love was so keen on smoothing Hole’s edges she even considered consulting Diane Warren, author of Aerosmith’s sappy megahit ‘I Don’t Want To Miss A Thing’. Her bandmates vetoed those plans, but gave the album its muscle and sparkle. Eric Erlandson’s guitars are pristine and hefty. Melissa Auf der Maur replaced Kristen Pfaff, who died of a heroin overdose two months after Cobain, and her melodic basslines and coolly delivered backing vocals help anchor the record. Billy Corgan, parachuted in when they hit a dead end, undoubtedly helped shape its sound. Making something so slick could get ugly – producer Michael Beinhorn used skullduggery and studio trickery to oust Hole’s incredible drummer, Patty Schemel – and fans could be sceptical. Yet what some saw as betrayal, Love saw as liberation. As she told True: “We have stock, but we also want to be populist.”

The results still sound fabulous. ‘Malibu’ is a gorgeous, longing swirl of Californian dreams, sighing melodies and burnt-sunset acoustic guitars. “Help me please/ Burn the sorrow from your eyes,” pleads Love, her voice sweeter than its customary snarl, as she summons hordes of angels to save a lover. ‘Hit So Hard’ is such a starry-eyed rush of dreamy, glimmering chords it makes you feel punchdrunk, while the galloping pop-rush of ‘Heaven Tonight’ scarcely sounds less indebted to Fleetwood Mac than their cover of ‘Gold Dust Woman’. If the latter’s chiming guitars weren’t indicative enough of change, its backstory was. Hirschberg’s allegation that Love used heroin while pregnant resulted in her and Cobain temporarily losing custody of their daughter, Frances Bean. The mess spilled into Live Through This, where she sent herself up as the mother from hell on ‘Plump’ and howled for her missing daughter on ‘I Think That I Would Die’. ‘Heaven Tonight’ isn’t about Frances, but it was written for her – a song to make her smile, rather than a document of misery.

But while Celebrity Skin is prettier on the outside, its gloss shouldn’t be mistaken for froth. Cobain’s death, the subsequent media circus and the turbulent Live Through This tour all took their toll, and Erlandson told Rolling Stone that other losses had weighed on them too, including Pfaff, Jeff Buckley, and both his and Auf der Maur’s fathers. That grief inspired its frequent references to drowning, both lyrically and in its packaging (among other allusions, the back cover repurposed Paul Albert Steck’s painting Ophelia Drowning).

There’s another motif which feels equally pertinent: confectionery. “He tastes like candy, he’s so beautiful.” “He’s so cold, give him a candy-coat.” “He’s so candy, my downfall.” “Their innocence tastes like candy.” Candy, delicious but health-damaging, is a fitting theme for the way Celebrity Skin’s songs can sometimes slip down like sugared pills, their sweet sounds masking bitter feelings. ‘Malibu’, for all its lushness, is a doomed rescue mission for a lost cause – and towards the end, there’s a moment when the fantasy slips away and those exquisite melodies get a little choppy, with Love’s voice fraying and knotting. “I knew love would tear you apart,” she spits, choking on ugly truths she can’t swallow down any longer.

“My sweet tooth has burned a hole,” she admits on ‘Hit So Hard’, her desire turning corrosive – and while its chorus is about a powerful orgasm, you can’t hear her coo “He hit so hard/ I saw stars” and not think of ‘He Hit Me (And It Felt Like A Kiss)’, which Hole covered several times. Even the child-friendly ‘Heaven Tonight’ is supposedly about a girl killed in a car crash en route to meeting her boyfriend. And then there’s ‘Awful’, a fiendishly catchy Trojan horse which uses its sugary, soda-pop melody to coat a scathing takedown of music-industry sexism. Love’s disarming cherry-pie yelp details how young women are screwed in all kinds of ways for all kinds of profit: “They know how to break all the girls like you/ And they rob the souls of the girls like you.”

It often feels as if Hole, rather than being in thrall to these brighter sounds, are bending them to their will. ‘Boys On The Radio’ (originally called ‘Sugar Coma’) is jangling and bittersweet, but its hazy guitar-pop belies a sadder story. It’s about a girl convinced her dead heroes are singing just to her, their words half soothing lullabies, half siren calls (“When the water is too deep/ You can close your eyes and really sleep”). ‘Dying’ is dark, brittle and uncomfortably intense, its murky stormy tension growing louder but never fully breaking. “I need to be under your skin,” she pleads, the desperation in her voice making longing sound like a threat.

Its politics can also be slippery. Love was renowned as a firebrand punk feminist, but was critical of any movement she felt clung too dogmatically to its ideals: she clashed with the riot grrrls and cursed Olympia’s underground scene. “It’s not about talent, it’s about purity,” she declared. “It’s about having a manifesto, and it’s bullshit.” It’s an unsurprising stance given Celebrity Skin’s accessibility, but occasionally she still seems sympathetic to the underground as it was pillaged, packaged and sold: there’s cynicism on ‘Awful’ (“It was punk/ It was perfect now it’s awful”), but also belief in countercultural power (“If the world is so wrong/ You can break them all with one song”).

On ‘Playing Your Song’, an assault of scuzzy guitars and snarling vocals, her rage spills in every direction. There’s anger for those responsible for cheapening righteous fury, and disdain for the charlatans who’ve reduced once-incredible sounds to hollow ersatz imitations. But there’s also contempt for those who lapped up the punk-purist snake oil: she reserves most of her jabs for a husk who’s become so cynical they can’t enjoy anything. “Hey you, don’t take it out on me,” she snaps. “You’re bored of everything/ You burned right out.” Autobiographical readings can be too easy, but it’s hard not to think of Cobain and his uneasiness with Nirvana’s success. One couplet seemingly harks back to 1994, when she told fans the Neil Young-referencing sign-off in his suicide note (“it’s better to burn out than fade away”) was a “fucking lie”: “I had to tell them you were gone/ I had to tell them you were wrong.” It’s an old ghost that possibly haunts the swampy, guttural racket of ‘Reasons To Be Beautiful’ too, in which Love offers another solution: “When the fire goes out you better learn to fake/ It’s better to rise than fade away.”

Less opaque are the haunting strings and rough acoustic guitars of the brittle ‘Northern Star’, a song so unvarnished it sticks out like a sore thumb. It starts with Love spilling her guts mid-sentence, as if she’s been repeating this same loop of anguish for hours, days, months, years: “And I cry and no-one can hear.” When she explodes, her howling, 30-fags-a-day rasp is at its most devastating: “No loneliness, no misery is worth you.” It’s a more plaintive cry of despair following the menacing industrial throb of ‘Use Once And Destroy’, which starts with dangerous electronic surges and builds to a violent blowout. Its title nods to both a lyric from Nirvana’s ‘Radio Friendly Unit Shifter’ and the instructions printed on hypodermic needles. As in ‘Malibu’, Love follows someone into the heart of darkness to save them from their worst impulses, but finds nothing but pain and dirt.

The bruised, beautiful gloom of ‘Petals’, then, makes for a fitting end, a twisted game of he-loves-me, he-loves-me-not that resembles an act of torture. “Tear the petals off of you/ And make you tell the truth,” sings Love darkly, finding more foul secrets in pretty things. “She’s too pure for this world,” she insists later. “This world is a whore.” The sweetness never lasts: pretty flowers torn to shreds, purity stained by ugliness, innocence defiled and corrupted. Like much of Celebrity Skin, it’s as sinister as it is sumptuous; perfumed honeysuckles full of deadly poison.

Hole’s own problems were becoming equally toxic. They went on tour in 1999 with Marilyn Manson, but quit after being booed offstage by his fans. Schemel was forced out, and Auf Der Maur left. Their label, Geffen, was acquired by Universal, and sued Love for failing to furnish them with five promised albums; she countersued and alleged they failed to properly promote Celebrity Skin. It was supposed to take them to a new level, but four years later they’d broken up.

In the documentary Hit So Hard, Erlandson reflects on the cost of ditching Schemel at Beinhorn’s behest: “We lost some of the soul … What the fuck were we thinking?” You could ask the same question about Celebrity Skin as a whole: they sacrificed old friends, old sounds and old ideals, and it can be tempting, now, to half-wish Hole hadn’t gone for broke and ended up so broken. But even if Hole’s Faustian pact didn’t deliver the mainstream-conquering success they craved, there’s something to be said for the fact they tried to beat the devil at his own game to begin with. “Everyone says they’re going to subvert the system from the inside and then everyone gets mad because no one ever does it,” said Love in 1999. Hole didn’t manage it long-term, either, but they tried their damndest. For those 50-odd minutes, they weren’t just the band with the most cake; they were able to eat it, too.