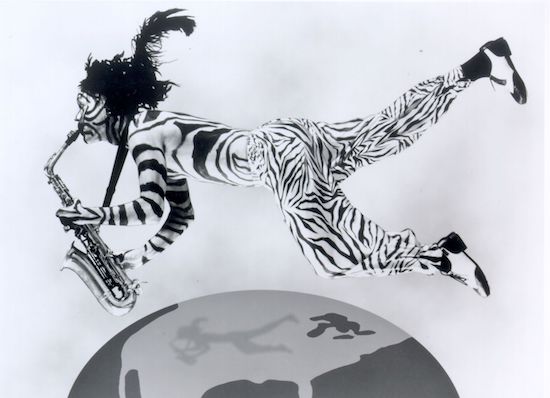

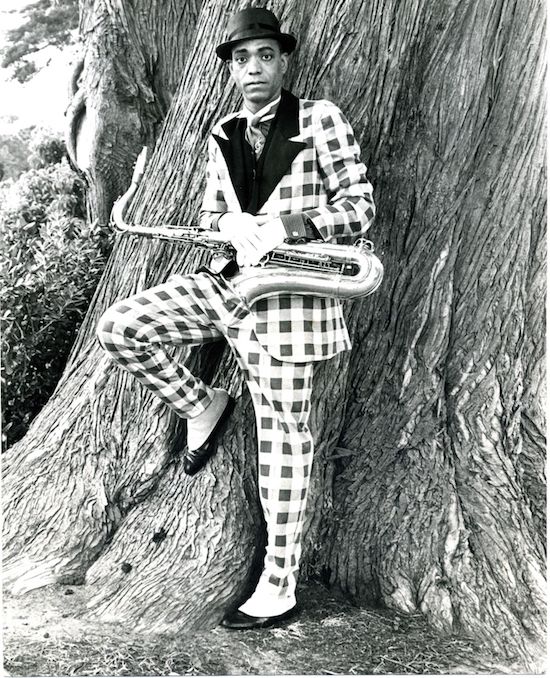

The saxophonist, multi-instrumentalist, tap dancer, actor and artistic director of the Pyramids, Idris Ackamoor, has joined us to talk about the late great pianist, poet and composer, Cecil Taylor, African roots and ritual, his work with incarcerated women in the Medea Project, and the recording of the new album with Heliocentrics’ Malcolm Catto in London. And as a bonus, he’s devised a ten track Pyramids primer, which you’ll be able to see listed at the foot of this feature.

With the release of the excellent An Angel Fell, the Pyramids’ third album since their resurrection in 2010, Idris Ackamoor’s reactivated spiritual jazz ensemble further cement their position as that rarity amongst returned bands, one whose current output has begun to eclipse the quality of their original recordings.

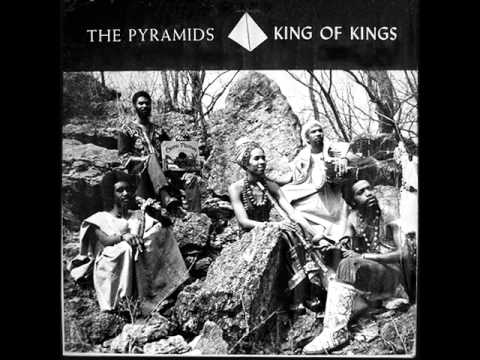

Walking a slightly different path to Sun Ra or the Art Ensemble of Chicago, The Pyramids were born out an Antioch College Ohio study abroad programme that saw the band heavily influenced by their time spent living in Africa. Three private press albums, Lalibela, King Of Kings, and Birth/Speed/Merging, were released before their dissolution in 1977.

As is often the case, the limited nature of the original pressings only served to add mystique and momentum to the group’s legend over time. Exuberantly entertaining and inspirational live performances heralded the group’s reemergence following interest from record labels in Chicago and Japan, and jazz and world music aficionado, Gilles Peterson. Idris Ackamoor talked to us from his home in San Francisco.

Early Days: Chicago, Antioch And Cecil Taylor

From my birth, up until I graduated from high school, the south side of Chicago was my home. The music I had was mostly classical training and band charts in those early years. When I graduated from high school, I went to a small liberal college in Iowa to play basketball. While I was waiting to hear from my application to Antioch, I went back to Chicago and that’s when I met my mentor and principle influence, the clarinettist, Clifford King. He was the go-to teacher for many of the AACM saxophonists. In the late 60s, the AACM [Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians] was making a huge impact in Chicago. Although I never joined, I took a couple of classes in harmony with Roscoe [Mitchell]. I also became very good friends with Don Moye. Of course, the Art Ensemble was very much of an inspiration to me, not only musically, but business-wise. Cecil came to Antioch for two years. In terms of my inspiration and influence, Cecil was probably my primary influence. I loved Cecil, as a brother, as a teacher, as a mentor – he was so encouraging. Cecil was non-competitive. Cecil was about participation. I remember the very first audition to get in the Cecil Taylor Black Music Ensemble had nothing to do with music, it only had to do with theatrical exercises. What was called at that time, sensitivity exercises. He would get the musicians laying on the floor and then you would crawl over one musician to the next, and you would experience Cecil’s direction, because he was not looking for the best technically competent musicians, he was looking for the musicians who could follow his directions most explicitly. Cecil taught me a lot about music, life, and more than anything, Africa. He had a class called music and the black aesthetic, where he would read his poetry and talk about the connections between Michael Jackson and African drumming, or Sly and the Family Stone. Cecil was the first person who obliterated the categories of music for me. Cecil loved to dance at our parties at Antioch. You’d put on a Michael Jackson tune, and Cecil would be the first person on the dance floor. He loved the total tradition of black music made in America and the African diaspora of music. He was so well read, that just being around him was an education. Prior to that, before he came to Antioch, I met another of my principle influences when I took a quarter where I went to Los Angeles and met Charles Tyler. He was Albert Ayler’s cousin and played alto on that crazy album Bells, with Sonny Murray on drums. If you put it on, it sounds like something from outer space. Charles died in 92. So, you could say I’m one of the last men standing of that great spiritual jazz renaissance out of the 70s.

Rhythm And Ritual Abroad: The Pyramids In Paris, Amsterdam And Africa

The Pyramids decided that we weren’t going to stay in Paris, because Paris was very well populated with a lot of African American jazz musicians. We went straight to Amsterdam, not knowing anybody, and that’s where the Pyramids began to work. We departed Holland for Africa, after about three months. We travelled to Malaga in Spain, and then we took a plane to Tangier, Morocco, where we spent a couple of weeks. Then we went to Dakar, Senegal, and we landed in Accra, Ghana, where we began our odyssey. We lived in Ghana about four to six months and from Ghana, we travelled to Uganda, where we stayed a couple of weeks, and then we lived for a while in Nairobi Kenya on a coffee estate. We studied the music of the Kikuyu and the Masai in Kenya, and in Ghana I took a pilgrimage into the north, where I participated in a ritual with a traditional Ghanaian priest, known as a juju man or tindana. It was called the ritual of the washing of the legs. I was in a grass hut out in the bush and the priest was chanting and playing a calabash rattle, whilst washing my legs with a bagre stick. The purpose of the ritual was that I would be able to walk anywhere in the world, unmolested. And I’ve got to be thankful, because all this time, 45 or so years later, I’ve been able to do it and had a wonderful experience, never was molested, never was robbed, thanks to the creator and to that ceremony. On our way back to America, Margot and I went to Ethiopia, where we went on a tour of the ancient sites. We went to Lalibela, Aksum and Gondar. In Lalibela, we visited the rock churches and we named our first album when we got back that we recorded in 1973, Lalibela. I think I was one of the first of my generation to actually go and live in Africa. A lot of African Americans were kind of frightened of that. We had been brainwashed initially in the 50s and early 60s, that Africa was not a place to go. With the birth of the black power movement of the late 60s, there was initially a kind of reawakening, a way to be proud of our ancestral roots.

Returning To The USA. Early Live Shows

People were always enthusiastic. When we came back, we were like the embodiment of Africa. We came back with African instruments, African costumes, we were completely influenced by Africa. So our stage performances were like music, costume, dance, rituals. We just mesmerised our audiences in those early days of our live concerts. They were really theatrical pageants. Even before we were really influenced by Sun Ra, because I hadn’t had much experience with Sun Ra’s live shows, we began to do our own promenades into the audience and our own costumes, so we were evolving from our own inner souls and our own African experiences, and our performances were really one of a kind performances. We began to perform around the Ohio area – Dayton, Cincinnati, Springfield. The Pyramids opened for Weather Report in Dayton Ohio and then they came to Cincinnati and the band opened for them there as well. Our conga player, Bradie Speller, began to play with Weather Report on some of their tours. We played around Antioch for a while and we also stayed there to record our second album, King Of Kings in 1974, at a 16-track recording studio in Chillicothe Ohio.

San Francisco And Birth/Speed/Merging

Our third album was definitely more dense. It was also more technologically advanced, because this was after we got out to San Francisco. Margot and I first landed in Oakland in the Summer of 74, and the two of us were like the anchors for the Pyramids to make their transition to the Bay Area. Not to long after that, Kimathi [Asante] came out, followed by Donald Robinson our drummer. We began to play in the Bay Area as the Pyramids. Around this time, we were playing with only one bass player, but Kimathi decided that he wanted to continue his education by taking another trip, to Egypt, so he left the band and went back to Antioch for a period, and around that time we began to add San Francisco musicians that we had met to the band. Which included Hashima Mark Williams, who is on the Birth/Speed/Merging album. Kimathi returned and by the time we recorded that album, we had two bass players. Kenneth Nash was our percussionist and Augusta Lee Collins was our drummer. So, my compositional concepts began to expand with the additional musicians we were using.

Hiatus For The Pyramids And The Beginnings Of Cultural Odyssey

What happened was, reality hit us. Being out of college, trying to make a living as a musician, we were slapped in our faces, because it became more and more difficult. Our last show was at the UC Berkeley Jazz Festival in 77. Then in 1979, I formed my organisation that I’m still involved with, called Cultural Odyssey – a non-profit, performing arts organisation to support my musical and theatrical life. I met my still, long time business partner, Rhodessa Jones. Rhodessa’s project is called the Medea Project. Rhodessa goes into the jails and makes theatre with incarcerated women, out of their own experiences, who then are allowed by the Sheriff’s department, under guard and handcuffed, to go to a major theatre for a two week performance run. This happens in the States, it’s happened in South Africa. We exported it from 2005 to 2012, every year. We were some of the first African American artists to come in the jails; into an all women’s jail outside of Johannesburg, the Naturena Women’s Prison. It took seven years until they allowed us to take them out of the jails to the state theatre in Pretoria to do a four-day weekend run. I assisted her, as assistant director and production manager. The experience is life-changing, I can really say. There are actually several women who have been with the programme since its inception in 89/90. Now it’s expanded, not to deal only with women who are ex-inmates or incarcerated, but particularly African American women who are HIV positive, together onstage, performing for sold-out audiences. All original writing that they’re involved with. Rhodessa gets the women to tell their own stories. Along with the Pyramids, this is my current main project for Cultural Odyssey. That’s been my foundation for 40 years, which has allowed me to never have a day job.

Tap Dancing And The Isadora Duncan Award For Choreography

I’ve studied with some of the great hoofers. My main instructor was Al Robinson. I was studying with Al when he was over 81-years-old. I’m probably one of the few repositories of his signature steps. Every elder tap dancer, and most of them have died out, had their own individual steps that they were able to pass on sometimes. So Al Robinson still lives on with me when I perform his steps. I’ve studied with Steve Condos and Eddie Brown, but I have my own style. I love Bunny Briggs, the paddle-and-roll style. It’s like you’re floating a fraction of an inch above the wood. I love movement and dance and it has continuously created a theatricality to our performances. I relation to the Izzie award, one person I call a collaborator and a good friend, is Rhodessa Jones’s brother, Bill T. Jones. Bill became famous because of his Broadway choreography of the musical Fela!. Since he was Rhodessa’s brother, we had the opportunity to do a performance called Perfect Courage. That performance was basically me, Rhodessa and Bill onstage, and it was one of the hottest shows of Cultural Odyssey’s history. We took it to New York, where it got great reviews. I feel honoured to be one of the few musicians to do a duet with Bill T. Jones. I was onstage with him, almost naked. Bill, of course, has got a body to die for, and me and him are sitting there onstage, in what’s called a dance belt. A dance belt is basically just a jock strap, which only covers your private parts and the crack of your ass [laughs]. That was just one part of the show, obviously.

From Small Pressings To Renewed Interest. The Pyramids Rise Again

I think the most that was pressed of the first two records was 1,000. Birth/Speed/Merging was more, although we didn’t sell that much more. After the Pyramids broke up, I wasn’t thinking at all about getting the band back together. I was very happy doing what I was doing. My music was soaring, my company was happening. Then I started to get calls from people. Giles Peterson called me, and he was doing this collaboration with Stuart Baker from Soul Jazz Records, on that beautiful book about revolutionary cover art of the 70s [Freedom Rhythm & Sound: Revolutionary Jazz Original Cover Art 1965-83]. At one point there’s a two page spread on the Pyramids’ three albums, because of course we were right in the mix of the early DIY generation of producing our own albums. A Chicago record label called Locust Ikef Records, called and they wanted to re-release the 70s albums. So we put together a contract, but before he was able to do that he called and told me to go over to Aquarius Records in San Francisco, because there was a CD of Birth/Speed/Merging there. I knew nothing about it. Apparently a Japanese label called EM Records released this CD unauthorised, but the guy whose label it was said that somebody masquerading as a Pyramid, came to him with the vinyl and said that they had the authority to give it to him to release. When I called him, he was very apologetic and he withdrew it from the market place. Then he decided to legitimately release the 2CD collection, The Music Of Idris Ackamoor 1971-2004. Then there was a big international theatre festival here in San Francisco in 2007 and Rhodessa Jones was one of the artistic directors of the festival, so I said to myself, this is a good time to do a record release show for the Japanese release. I brought all the original members out to do the weekend festival. Not too long after that, an agent from Berlin called and wanted to do a tour with the band. He had never heard the band live, he just knew us from our reputation and the albums. So that began the touring life and the rebirth of the Pyramids in 2010.

Touring And Shifting Lineups. The Pursuit Of Quality

Bradie, the conga player, is on the album An Angel Fell but Bradie had a very bad health scare in 2012. He’s ok now, but he had to stop touring for about four or five years, but subsequently he just came back on the Summer tour. Several of the musicians, like Kenneth Nash, also had health issues. Basically, as we get older, health is more important than anything. I look at things now how ‘Trane or Miles Davis looked at their bands. Many people came through their bands. I’m looking at the Pyramids as a repertory of wonderful musicians, some of them original, some of them not, but all of them usually have a long standing history playing with me. As much as I’d like to keep the original band together, it’s difficult because of age, business and other aspects. When you get to be 60, it’s very hard for a musician to go out on a three week tour for $1,000. I’ve got younger musicians too, who are also very talented, but want the experience and exposure. Then you have older musicians, like Sandy Poindexter, my violinist, who is kind of retired, but has a love of touring. The most important thing is quality. I have always been the 99% leader of the band from its beginning. 99% of the compositions have always been mine. I’m the only one who, thanks to the creator, has never missed a concert in 50 years. I guess that tap dancing helps me out a little. I’ve always been very proud of every band I’ve brought to Europe.

Recording An Angel Fell At The Heliocentrics’ Studio In London

It was an experience of a lifetime. Malcom [Catto] is an amazing engineer. We got along very good during the process. London is one of the places I dream about in terms of the history, Jimi Hendrix being over there, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, everybody that came through there, as well as the new jazz movement, Shabaka Hutchings and his Sons Of Kemet. It’s a wonderful milieu. It kind of reminds me of where I am in San Francisco, because where my company is located, we have a cultural centre. Malcolm’s studio has a social centre above him on the first floor. His studio is in the basement. Being there, it felt like being a part of the community. This record is a thrilling development for me. You know, your recordings are a little bit like your children, so you don’t want to put one of them up against the other but I do feel like this is a culmination of everything that went before. I put a lot of my heart and my soul into it, my spiritual and political consciousness into this album, and I think I had the right musicians performing and recording. Of course, we couldn’t have recorded it at a better time because it was right at the end of our very extensive Summer tour. So by the time we hit the studio we were flaming, we were hot.

A Pyramids Primer: Ten Tracks For The Uninitiated

‘Queen Of The Spirits’ [from King Of Kings, as sampled by Bonobo on ‘Days To Come’]

‘Black Man Of The Nile’ [from Birth/Speed/Merging]

‘Clarion Call’ [from We Be All Africans]

‘Soliloquy For Michael Brown’ [from An Angel Fell]

‘Nebulosity’ [from Otherwordly]

‘Boundless Eternity’ [from Otherwordly]