A quarter of a century isn’t that long in the grand scheme of things, but in the life of a genre it’s an eternity. Today, it’s a given that rappers from the UK can become – and, indeed, in many cases are – household names. That can, of course, be both blessing and curse, as we have seen when artists have been credited with helping drum up the youth vote for Jeremy Corbyn one minute only for the entire subgenre of grime to be castigated for fuelling the rise of knife crime in front-page national newspaper "exposés" the next. But in the early 1990s, if people outside the very limited confines of the scene itself ever mentioned British hip hop, it was as the punch line to a laboured and unfunny joke. The stereotype was unflattering and distinctly unappealing: losers copying American style, slang and even accents, making music that was a pale imitation of the string of great records finding their way into UK shops from across the Atlantic as the music’s golden age shape-shifted into something new and commercially dominant.

From the inside, though, British hip hop was a very different proposition – partly for some of the reasons those who chose to look down on it did so. True, nobody in UK rap was earning a living from it: but that meant that those who were making it were doing so for all the right reasons. Involvement meant total commitment to the art. Skills were sharpened. Hunger – metaphorical and, on occasion, actual – made the music stronger. There was a real, creative reason for each record to exist: every last track, no matter what objective level of distinction or merit one might consider it held, really meant something, and had required its makers to answer an unending sequence of searching questions about their priorities in art and in life.

And then there was Blade, who was on another level entirely.

There has probably never been an artist who took independence, determination and self-belief to such absolute ends. Blade had learned those lessons early: born to ethnic Armenian parents in Iran, he was sent to boarding school in London as a pre-teen, only for the revolution to leave him stranded there, with no chance of returning, no way of his parents sending him money, and no means of support. He washed dishes to make ends meet. Rap became his lifeline and a kind of a guiding force: learning raps from records and pretending they were his own, he found he had a facility for the art form, and could impress peers who otherwise ignored him. He discovered a natural aptitude for beatboxing, and formed a partnership with the emcee Merlin (who would later have a hit as a guest on the Bomb The Bass single ‘Megablast’).

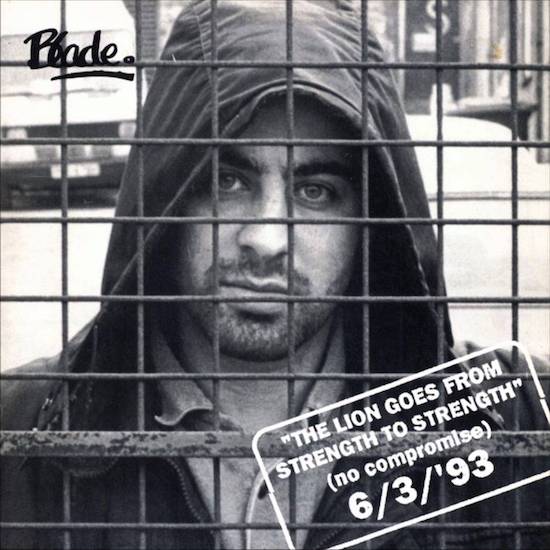

His first stab at making music was rapping the instructions to a board game about the music industry, but in 1989, Blade got serious. He teamed up with producer 2000 Adee and cut a debut single, ‘Lyrical Maniac’. According to the story as he told it in a 2010 sleevenote for the Original Dope/Cherry Red reissue of The Lion Goes From Strength To Strength, he financed the pressing of 300 white-label 12" copies by pickpocketing people in an amusement arcade – receiving the copies 33 days before the end-of-year deadline to either make a record or stab himself. ("So what if I was stealin’?" he rapped on record a year later: "At least I was doin’ it with feelin’.")

Selling them proved just as tricky: Blade wandered the streets with a bag full of records slung over his shoulder, trying to persuade strangers to buy a copy. He was on a platform at Charing Cross, contemplating suicide, when a woman asked him if he was OK: he told her his story and she told him Tim Westwood had played his record on Capital the day before. She bought a copy – the first he’d sold. A few weeks later, and after a repressing from a label set up by a record shop in Lewisham, he’d shifted 9,000 – getting on for three times as many copies as most UK hip-hop 12"s generally managed.

The following year’s single, ‘Mind Of An Ordinary Citizen’, was even better. Both it and its b-side, ‘Forward’, showcased a unique writing style, fragmentary images stitched together in ways that oughtn’t to make sense but instead seem to weave complex alchemical patterns. ‘Mind…’ works as an abstract manifesto; every verse in ‘Forward’ ends with an invitation. The music was next-level, too. ‘Mind’ is kicked off by a bass line Blade played on a piano and its low-pace thump set it apart from the super-fast style London rap was developing at the time; ‘Forward’ was quicker even than Hijack, Silver Bullet and Gunshot, but pulverised Baby Huey’s monstrous ‘Listen To Me’ in the process, so was funkier and heavier than anything his contemporaries were attempting.

The single came out on his own label – 691 Influential, named after the area code for New Cross, where Blade lived. Again, the recording was entirely self-financed, as was the manufacture. And even though he’d struck a distribution deal to get it into shops, Blade still turned to the old methods: he became a fixture outside hip hop specialist Groove in Soho, selling copies in person. Word was spreading, and the personal touch was now his calling card. On the back of the sleeve, where there’d normally be an address and phone number beneath the label logo, it said: "If you need to contact us just ask anyone in the Lewisham Borough." This actually worked, as I soon found out as one of the messages I’d left with shopkeepers and railway-station workers in New Cross led to a phone call, and our first meeting a few weeks later.

This should be the part where the "full disclosure" text gets rolled out, because, for the next few years, I became Blade’s press officer. However, to talk of that as if it were a conventional business relationship would be stretching the point. I agreed to work, initially, for expenses only, with a fee to be decided once some money was made. That moment was to remain forever just over the horizon, though there may have been a payment of a few hundred pounds some years later, in lieu of replacing a DAT machine I’d loaned him circa 1993 which hadn’t survived an accident on tour. Yet Blade had this way of making anyone in his orbit feel that the mission was what mattered, not the money. He had something about him that made everyone just want to pitch in. A well-known radio DJ gave him an Akai sampler; at least two chart bands, at different times, paid for studio time; the editor of the biggest-selling music magazine in the UK bought a copy of his album, paying in advance. Then there was the friend – they’d met through music – who popped round for an afternoon, doubtless being roped in to answer the phone while Blade had to pop out to run some errands, who left £2000 in cash with a note suggesting it be put towards studio time. So, alright, I guess I’m not really able to tell this story from an entirely impartial perspective; but that’s not because my loyalty has been bought.

All things considered, for the next couple of years I ought to have been paying him. Watching Blade make single number three, ‘Rough It Up’ was an education and a half. Adee had stepped back from production, but Blade was stepping up. The partnership he’d formed on ‘Lyrical Maniac’ with the mild-mannered bass-playing genius No Sleep Nigel had already reached a level of intuitiveness where they both knew what every track needed, and were more than willing to work hard to get it right. Nigel earned his soubriquet via sessions with MC Mell ‘O’ and others on the London hip hop underground for his willingness to do graveyard-shift all-night sessions. These were popular with British hip hop artists because studio time was significantly cheaper when ordinary musicians were asleep and studios couldn’t get any clients who had record labels to pay the fees. But Nigel’s extensive string of credits hadn’t come about solely because he was OK about unsocial hours: he knew how to work the sampling tools of the hip hop trade; had a professional musician’s depth of understanding of music and songcraft – yet he wasn’t condescending or snobbish about loops, breaks and rhymes, as so many steeped in more traditional musics can so often be; and was as determined as any artist to make the recordings special.

Nigel always preferred the credit ‘engineer’, yet to my mind he more than merited the designation ‘producer’ on every last one of the many UK rap sessions he was involved in. Blade may have written and directed the musical lines, but the way the tracks sounded in the final mix was a product of both their creative decisions. Crucially, both Blade, who’d been listening to hip hop since before he hit his teens, and Nigel – whose own musical passions lay more towards jazz and funk – had in-depth understanding of how to take the basic ideas they began with and shape them into musically coherent compositions. It was on these sessions that the signature style of their partnership was minted: samples delicately and meticulously layered into huge, tasty slabs, a sound as big as the Bomb Squad and as elegant as a symphony. They spent hours – entire nights in a studio called Joe’s Garage, dawn breaking over the rooftops of Battersea – on details in ‘Rough It Up’ and its two b-sides that nobody listening to the tracks will ever even notice.

The record repeated the success of its two predecessors – knocking on the door of 10,000 sales – but made Blade less money. After shops and distributors took their cuts, the cash that was returned to him barely covered the studio costs and the pressing. A video was made – obviously, for one of the b-sides; d’oh! – and even though the filmmakers essentially donated their services for free, just the cost of duplicating some VHS copies to get them out to TV stations proved difficult to find.

On top of that, the specific outsider status and widespread negative stereotyping of British hip hop meant that the advantages independence conferred on musicians from other genres did not apply. Blade’s single-minded determination to stay independent ought to have endeared him to the more open-minded members of the post-punk crowd who favoured releases on small labels over those put out by majors: the ethos would have struck a chord even if the music was of a different stripe. But the shops that sold Blade’s records were specialists supplying DJs and clubbers – they didn’t send returns to the compilers of the independent charts carried by the music press, so that opportunity to gain some visibility beyond the walls of the tiny world of UK rap was denied to him. If those fans had their curiosity piqued by the decent reviews the record got in the music weeklies, they had to have specifically ordered a copy from the record shop they usually visited if they’d wanted to buy one: the distributors tried hard, but struggled to sell in copies to shops that weren’t routinely stocking rap records. Blade recorded a John Peel session but there was no obvious means of following up on any interest that may have gained from fans of the records Peel normally played.

Even opportunities to play live were few and far between. Clubs wanted American rappers if they wanted rappers at all. Not only was the British rap audience small, they tended not to drink in the quantities rock and indie fans routinely did, so promoters and venue owners were less inclined to book an act that might only bring in 50 people when another booking might not make them any more money on the door but would quadruple the take behind the bar. A perfect example of how close and yet so far apart London’s indie-rock and homegrown-rap scenes were came between 10:30 and 11pm every fourth Monday outside the Borderline, a basement club off the Charing Cross Road, when a student of cultural insularity could watch agog as indie fans and the hip hop crowd literally walked right past each other once a month. After the early-evening gig had finished and its audience had left, the club re-opened to play host to Flavour Of The Month, a hip hop night hosted by Choice FM’s rap DJ (first Steve Wren, then 279). As the gig crowd left, they passed the Flavour folks queuing to get in for their tightly rationed, 12-times-per-year three hours of hip hop records, live performances and an open-mic freestyle session. This is where The Roots, then living in a rented house in Kentish Town, made their London live debut; a show at Flavor became a rite of passage for any London emcee. Yet it was never included in the live-music sections of the listings mags, never appeared in the ads that the Borderline took out in the music press. You went because you knew about it, and you only knew about it if you went. (Or if you listened to Choice.)

Something had to change, and – let the record show – Blade was the one who changed it. Survival Of The Hardest Workin’ – a mini-LP – saw him going back to the approach that had served him well with the first few hundred self-pressed copies of ‘Lyrical Maniac’. No outside label, no distributor – he’d sell copies in person. Gigs would be booked, but he’d support bands from other genres and take a modest, cost-covering fee if that was what it would take to get him in front of a potentially interested audience. Over the next three years he played gigs with everyone from techno-bhangra fusioneers Fun^Da^Mental and psychedelic rock trio Dr Phibes And The House Of Wax Equations to platinum-selling indie heroes Carter The Unstoppable Sex Machine. And, with a public profile burgeoning courtesy of the interest journalists had taken in ‘Rough It Up’ added to occasional blurts of radio play, there was the possibility of converting casual attention into occasional sales. Blade registered a PO Box number and, when copies were sent out to media, reviewers and DJs were encouraged to include the address and price details in print or over the airwaves.

None of this would raise an eyebrow today, but in the pre-internet era, all of these were highly unusual positions for any artist to adopt. No sales through shops meant zero chance of ever appearing in any charts, and with everyone from radio-playlist compilers to live-venue managers relying on chart placings to guide their thinking on what got played and who got booked to perform, conventional wisdom suggested this was commercial suicide. But Blade’s records had sold better than most releases that topped the indie charts, and he’d never reaped any of the supposed benefits: there was nothing for him to lose. Playing support slots to non-rap acts might make it look like he was ignoring his natural constituency, and imply that he was just starting out – surely someone with his sales figures should be getting more money and better billing? But it made more sense to get paid £50 or £100 per gig and play 50 of them a year than hold out for £500 per show and only play one or two – British hip hop gigs, and the fan base for same, remaining stubbornly elusive at this point in time. Fans of the headliner were, as Blade saw it, potential Blade fans who just hadn’t heard of him yet. And his wisecracking exuberance and infectious enthusiasm made him a natural live performer: he was convinced that he had a chance of winning over any crowd, whether they were rap fans or not. (Over the following years he would prove the point repeatedly.)

Orders duly began to arrive through the letterbox of Blade’s New Cross flat: a trickle that never quite made it up to the kind of level you could call a flood, but the numbers started to mount. Blade mailed every copy out himself, writing the addresses by hand on the cardboard envelopes. The totals didn’t quite match those of the preceding singles – my recollection is that he shifted a shade over 5,000 between the postal orders and the in-person and after-gig sales – but there were no percentages to hand over to retailers or distributors. The new strategy had proved an unqualified and total success: it was the first time he had made any money. (All of which was ploughed back into the music.)

Of course, none of this would have mattered if the records he was making hadn’t been any good, but Survival, while in retrospect very much a transitional or almost a place-holder release, more than delivered on the promise Blade made everyone who showed sufficient faith in him to hand over their money. The title track was both the perfect introduction for anyone investigating him because they had been intrigued by his single-minded independence, and a concise encapsulation of where he’d come from and what he’d learned so far. It also moved his production and lyrical styles forward subtly but significantly, its layered, noisy slap of a beat attracting comparisons to Public Enemy that were as inevitable as they were merited.

But it was what came next that would define Blade. Everything – the music and lyrics; the form they were delivered to listeners; and the means by which they were created and delivered – would be ratcheted up further. So he conceived of an unprecedented project: a double LP, never before done in hip hop, and funded through the kind of subscription model that was unknown and untested in popular music. Blade announced the title of the project before he’d even written – never mind recorded – a note. Fans were asked to pay for the record in advance: £10, plus £2 for postage and packing. In return for showing 12 quid’s worth of their faith in him, they’d get extras in return: their name included in the lyric booklet that would accompany the double-vinyl, gatefold-sleeve package; and a free 12" single, comprising additional tracks that wouldn’t be included on the album, not to be made available to anyone but those who sent advance orders (he was as good as his word, too: ‘They Ain’t Shit To Me’ and ‘Clear The Way’ were the tracks in question, the free record eventually pressed on white vinyl).

Again: looked at from a 2018 perspective, this doesn’t sound so remarkable – artists come up with similar strategies to persuade fans to invest up-front in their projects quite often these days, and platforms such as Kickstarter provide easy access to the mechanisms to achieve it. But in 1993, Blade was doing it all through the PO Box and on the phone – not that he could take card payments, of course. The phone option was necessary because radio stations weren’t keen on taking up valuable air time by reading out the price and PO Box details, but were usually willing to read out a phone number. Blade installed a second landline in his flat, and connected it to an answering machine: but, more often than not, he’d pick up whenever it rang. He then used his charm and humour to convert mild curiosity into a sale – keeping fingers crossed that the person he’d spoken with would not just write the cheque, but also get around to putting it in an envelope, buying a stamp, and making the trip to the post box before they forgot all about this strange rapper with the unplaceable accent and his quixotic quest to sidestep the entire infrastructure of the music industry.

In a sense, it was all just the next logical step along the road Blade had been driving down since his first visit to a recording studio. But there was one important difference this time. As the advance-order cheques began to pile up on his doormat, Blade was under real pressure from his audience for the first time. It was one thing having people sending him money for a record that already existed, quite another when he’d yet to record a note.

The thought that he might fail to deliver never occurred to him, but other things were going on in his life that could easily have derailed his plans. With only one track in the can, his career-long DJ, Renegade, opted to sever the partnership and join London rap group Son Of Noise. Money – always in short supply – had become an existential problem. His relationship was at breaking point. His father was dying. Completing the album went beyond an obsession. ‘Lyrical Maniac’ was no longer just a song title, it was tantamount to a diagnosis.

Rather than crumble, Blade simply turned all this stuff into the art he seemed to have no choice but to create. Lines on the record that might skip past some listeners often contain commentary on a life that threatened to run way beyond his control. "Mice runnin’ around on my carpet" was all too true: and they were easy to see when they popped out, because Blade had sold most of his furniture to help pay for studio time. "The power’s comin’ straight from my bracelet" isn’t a Wonder Woman fantasy, but a reference to a piece of jewellery that had been passed on to him from the father he’d not been able to see in years. Renegade’s scratches on ‘Heads Are Forever Boppin” were kept, and Belgian DJ Grazhoppa was brought in for the rest of the record: the saga was summed up in the nigh-on-perfect couplet "Steps I wanna take, records I wanna make/My DJ with Son Of Noise? Cut – break". Blade’s girlfriend would soon give birth to a child the record would, largely, be responsible for feeding, and the tensions his relentless focus on the album, and on pouring every last penny into making it the best it could possibly be, caused an understandable, and mercifully temporary, breakdown in their relationship – "Now she’s gone, sick of a street kid" wasn’t just a poetic image.

And yet the record is shot through with an indomitable spirit: of defiance, of individuality, and of supreme belief in the power that hip hop had had on Blade, and the strength it had given him to find his place in the world. Despite the desperate situation he was in, his humour was paramount, evidence of it peppering all four sides. Not once does the music succumb to doubt or self-pity. If you didn’t know any better, you’d swear you were listening to someone who was just having the greatest hoot possible throughout the making of the record. And, to be fair, you’d be right: the studio was Blade’s playground and he was in his element while he was there. The time for worrying was only when thoughts turned to how to pay for the next session, where the next meal would come from, and whether it would all be finished in time for his son’s birth – that is to say, all the time when he wasn’t in the studio. In the moment, the work was all that mattered. As he put it in ‘Take It To The Edge’: "This is all I got to live with – music, music, music".

The lyric booklet – elaborate, large-format, no-expense-spared – records the date on which each lyric was completed, allowing an alternative, chronological track listing to be assembled should a listener so wish. The final sequencing was based around four sides of vinyl, with each having at least two anchoring-statement tracks that perhaps ended up getting worked on a little more extensively than some of the other cuts that sat elsewhere along the same groove. Sides one and two, in particular, are masterpieces of sequenced construction. Sometimes the production is deliberately simple: ‘It Feels Good To Be A Lunatic’ is just one scratchy loop (I think this is the track made from an LP Blade found a broken copy of in a junk shop- a chunk had gone, so the record looked like a PacMan made out of black plastic, but the break he wanted was on the last track, so he was more than happy to pay whatever was being asked) while ‘Start The Revolution’ – an effortless simulacrum of the DJ Muggs style from a rapper-producer more generally associated sound-wise with The Bomb Squad – is, by comparison to most of his work, uncluttered and understated. Yet never does anything sound half-cocked or undercooked.

Even tracks intended as lighter fare frequently pack a considerable punch. Take ‘How To Raise A Blade’, essentially an extended introduction to the blistering sub-title track, ‘No Compromise’, and which has no conventional production to speak of at all. Instead, over random piano doodling and some slapping of a table, Blade sketches in a potted biography that tells us all we need to know about who he is and why he chose the particularly complicated and difficult path he took. ‘Silence Is Better Than Bullshit’ is the sound – literally – of a man eating a bag of crisps, its title intoned, matter-of-fact-ly, at its close, distinctively and eruditely skewering those who make music for reasons less principled than Blade’s. Nigel makes an appearance at the end of ‘Fade ‘Em Out’, playing the part of "Simon Ripoff from Bullshit Records" all too believably (the script for which was derived from a real, and recent, answerphone message Blade received from the head of a British rap label who’d passed up the chance to sign him before ‘Lyrical Maniac’ but who, having seen him generating a fair head of steam, now wanted to step in with a magnanimous offer of "professional help").

But it’s those "big" tracks, at least a couple per side, that reveal the depth of Blade’s greatness, and the excellence of his and No Sleep Nigel’s musicianship and production craft. ‘Keep It Goin’ On’ begins inside a storm and doesn’t let up, its bricolage of samples laying down a dense fog of war that sets the scene for the battles to come; in the title track and its side-three bookend, the swaggering battle rap ‘…Or Get Crushed Like A Pumpkin’, there are long, rolled-in samples, left in the song far longer than anyone else would have dared. ‘No Compromise’ rattles and fizzes, a drunken piano riff propelled by parping bass made by manipulating sampler controls in time to its relentlessly propulsive beat; the bass line on ‘Dark And Sinister’ – a last-minute collaboration with Mell’O’, the album’s only guest – was made by sampling and pitch-shifting the buzz of a set of hair clippers. Also not often commented upon, but more than worthy of note: throughout, Blade’s performances are outstanding. He wrote because he had things to say, but the ways he found to say them and to give them aural interest are at least the match of their content. Just as a line’s syllabic pattern starts to become predictable he’ll flip it into an unexpected rhythm; words are played with, swirled around the mouth like they’re being tasted, then interrogated, reconfigured, their parts broken down and rebuilt into new shapes.

There are a few lyrical flourishes that seem a little strange, most perplexing of them a fixation on attire, as if Blade was constantly being upbraided for not spending money on his wardrobe ("You won’t see me wearin’ trendy boots" being this writer’s personal favourite, though it’s a close-run thing between that and "And when I talk to record dealers I never wear Filas"). The jokes are silly, but endearingly so – whether it’s the name-calling banter between Blade and Nigel that kicks off ‘How To Raise A Blade’ or the moment in ‘No Compromise’ where the track appears to stop, only for Blade to return with the playground-game taunt "Cabbage". But for the most part, this is a record about being independent, about not giving up, about refusing to do what other people think you should when they can’t possibly see things from your perspective.

There will probably never be an album that examines creative independence in so thorough, detailed and extensive a manner. There isn’t a track that doesn’t touch on the topic, and most are entirely dominated by it. Yet each approach feels fresh – every new angle taken revealing new nuance and detail. Whether he’s rapping about the nuts and bolts of making a record (there are lines in ‘100%’ that namecheck the brand of magnetic tape being used on the multitrack machine) or committing more commercial suicide by cutting off possible sources of promotion and exposure ("I don’t trust the Capital Rap Show/Because it ain’t rap anymore") there’s always something to shock or surprise. And the analysis is erudite throughout. Take ‘The Lion’ itself – a magisterial dissection of the laziness, cronyism and ineptitude that conspired to keep hard-working talent at arms length from commercial success, the track nevertheless is filled to the brim with the sense that, had hardship and adversity not been there to overcome, bonds would never have been forged, nothing worthwhile would have been created, and the music would have no heart:

"I looked around, and what do I see?

So many brothers sign their names on the line but they ain’t free

When it comes to the business you got to witness the lyrical fitness

‘Cause we’re in this together

Forever more this type of rapper’s stayin’ raw

They can’t ignore – I hit ’em for a sixty-four

Pick a bone, pick a bone, pick a bone picker

Name is on the sticker and I’m the rhyme kicker

Trouble Funk – trouble the funk, this is what you get

Place a bet

On your marks, get set,

Go: you go, you go, you go

You did it for the record – can you do it for the show?

Well I don’t think so…"

That the record got finished, that it exists at all, is victory in itself. That it went on to sell so well that Blade was persuaded not just to sell some copies through shops, but to press a CD version (naturally, this vinyl fundamentalist made sure that those opting for the enemy format got a truncated version: it wasn’t until former Hip-Hop Connection editor Andy Cowan coaxed Blade into sanctioning the 2010 reissue that the entire thing came out on that format) was vindication of his strategy, vision and skills. He kept at it, too, though subsequent records were a little more conventional in their business approach. Yet even in this regard Blade would ultimately be proved prescient, albeit in circumstances he would certainly never have chosen: his distributor went bankrupt, owing him money for two years of record sales, in part hastening a retirement from music that he’d been contemplating for some time after becoming a father and moving away from London in the mid-2000s.

In between was the record that put him, briefly and perhaps somewhat uncomfortably, into the mainstream that The Lion Goes From Strength To Strength showed him in permanent opposition to. The Unknown, a collaboration with Kingston-Upon-Thames producer/DJ Mark B, was released on a subsidiary of Virgin in 2000 and, building on years of work by both men allied to the promotional fuel of a major, saw them have a genuine hit. ‘Ya Don’t See The Signs’ got them on Top Of The Pops, touring with Feeder and supporting Eminem at stadium gigs. There was a sold-out London headline gig, at the since-demolished LA2, during which a visibly and audibly emotional Blade got down on his knees and kissed the stage, overcome by the way that the audience he’d brought along with him – all those "we"s in his lyrics refer not just to those inside his camp but to everyone who’d ever bought a record or a gig ticket, or even just lent a sympathetic ear – had finally grown to the kind of size where making something that looked like a living from this thing might just be possible.

But it’s that album’s title track that best brings this story to an end. Over an acoustic-guitar loop and vocal hook, taken from a 1971 LP by an Austrian psych-folk band called Zakarrias and dripping with precisely the right combination of drive and melancholia (and with bass played by No Sleep Nigel), Blade delivers three verses laying out exactly where he, Mark and Nigel had been, and why they would never row back from making their music their way. ‘The Unknown’ stands, now, as Mark’s literal epitaph – he passed away in 2016, news of his death conspicuous by its absence from every commercially produced outlet that covers today’s generation of British rap stars – and as the track that best explains where British hip hop came from and what it had to overcome. And, like The Lion Goes From Strength To Strength, you leave it convinced that this music will last forever. In large part, that’s because it was given its power by those who were committed to it back when being committed to it meant you were guaranteeing yourself nothing but struggle.