All images: Courtesy of TASCHEN

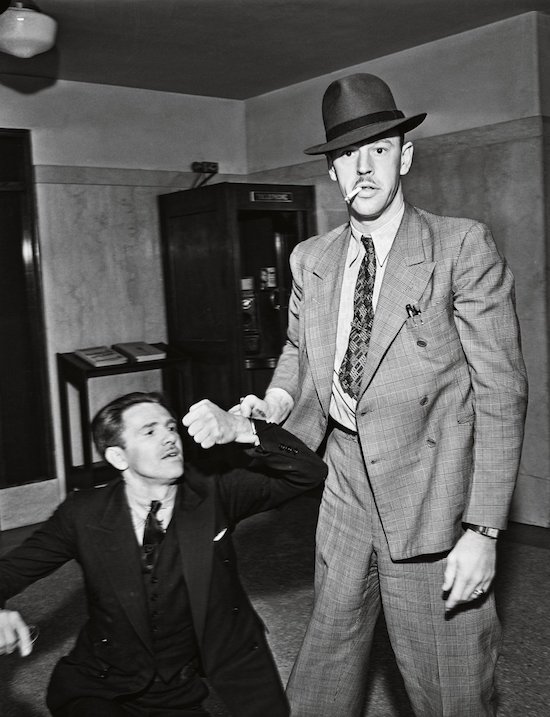

Almost from its start, Los Angeles had a reputation as a hellhole. In the mid-1800s the city was filled with murderers, vigilantes, thieves, and prostitutes. Streets were rutted paths where mongrel dogs roamed and dead animals were dumped. L.A.’s first bit of notoriety in the national headlines was spurred by the massacre of Chinese immigrants near the old city plaza on the Calle de los Negros. Commonly known in those days as “N****r Alley,” it was described as “. . . a dreadful thoroughfare, 40-feet wide, running one whole block, filled entirely with saloons, gambling houses, dance halls, and cribs. It was crowded night and day with people of many races, male and female, all rushing and crowding along from one joint to another . . . N****r Alley was a madhouse, filled with a mass of drunken, crazy Indians, of all ages, fighting, dancing, killing each other off with knives and clubs, and falling paralyzed drunk in the street. Every weekend three or four were murdered.”

In l871, this crowd experienced a killing spree that made national headlines. A Chinese immigrant, shooting wildly in the streets, accidentally hit a white man. Within minutes, denizens of the area swarmed the Chinese enclave, lynching, ransacking, stabbing, and beating “the heathens.” Eventually, nineteen victims were found dead. The grand jury indicted 150 men, with six sent to jail. Several days later, the six were released on a technicality. A pattern was set. It’s no wonder the city was given the cynical sobriquet “Los Diablos” by newspapers around the country.

Things changed as the century turned, but not much. Corrupt city officials and a police force of dubious reputation greeted masses of gullible newcomers who flocked to the “Athens of the West.” Many transplants found plenty of sunshine but little else. Water – a key ingredient that was brought to the Southland under questionable circumstances, making millions for a privileged few – had in just a few years transformed the desert into a mock Eden replete with imported vegetation and made-up architecture. Fortunes were made on oil and land, scandals ensued, and crime became part of the picture. The population rush unearthed scam artists, fakes, frauds, and nut cases who joined the parade and were quick to take advantage of the situation. To fill their physical and mental voids, many newcomers joined clubs for the lonesome or sought solace in healers-of-the-soul––evangelists who rushed to assuage the “lost sheep” with calls for prayer and money.

In the early part of the 20th century, Los Angeles seemed like many other large American cities on the rise. Corruption and vice came with the territory. What made L.A. different was how new it was, its topography, the omnipresent car, and Hollywood. The car made a big difference. Other cities had developed around traditional horse-drawn vehicles or railroads, and their growth was usually hard, steady, and finite. L.A. was a 20th century city and the first metropolis to come of age with the automobile as its primary means of transportation. With 500 square miles filled with roads, L.A. had plenty of leeway and the city boomed. Hollywood was part of that boom. The mere mention of its name made headlines blossom quicker than any other city in the world. Hollywood set itself apart from the rest of the world and made everything seem larger than life. It was an easy mark, and a seemingly ceaseless fountain of inspiration for writers.

With the onset of Prohibition, problems increased. A dry city was still a thirsty city, one that had to be supplied, and plenty of hoodlums bribed local law enforcers to place a keg or case into the right hands. Culver City, “The Heart of Screenland,” was a case in point. Home to MGM, Hal Roach, Ince, and a host of other studios, its main drag, Washington Boulevard, was a hotbed of speakeasies, gin joints, roadhouses, and cafés. Film money and the town’s “open” reputation brought crowds to back rooms filled with gambling, bookmaking, and prostitution. The city soon built a racetrack, boxing ring, and dog racing arena – all magnets for hoodlums. With direct access to Pacific Coast rumrunners and local stills, the town was afloat in illegal booze. The Culver City Police Department was notorious for looking the other way, losing evidence, and bungling raids, so life and crime went on undisturbed.

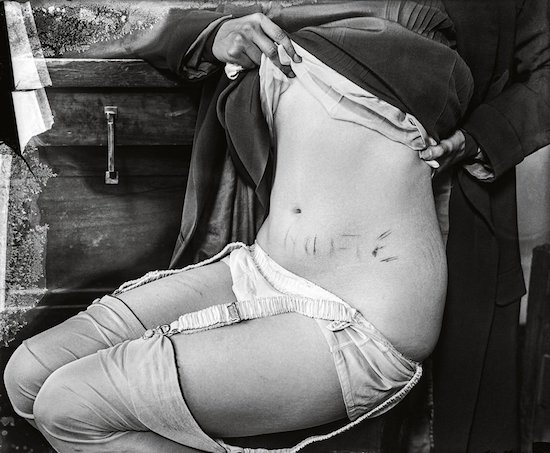

Culver City wasn’t alone. Venice, Vernon, and the outlying suburbs of Southern California seemed to have an unquenchable thirst for liquor, vice, and corruption – and you could always count on Hollywood to make national headlines. The film industry, firmly entrenched by the ’20s, provided more than enough money for the movie colonies’ excesses. A series of scandals early in the decade finally brought to the front page what had been simmering for years behind closed doors: Fatty Arbuckle’s alleged rape and murder of Virginia Rappe, the drug-related death of Wallace Reid, and the murder and questionable sexual orientation of William Desmond Taylor gave the public a ringside seat to Hollywood. Orgies, hoodlums, ignominious death – Hollywood had it all.

Dark City: The Real Los Angeles Noir is available now from Taschen