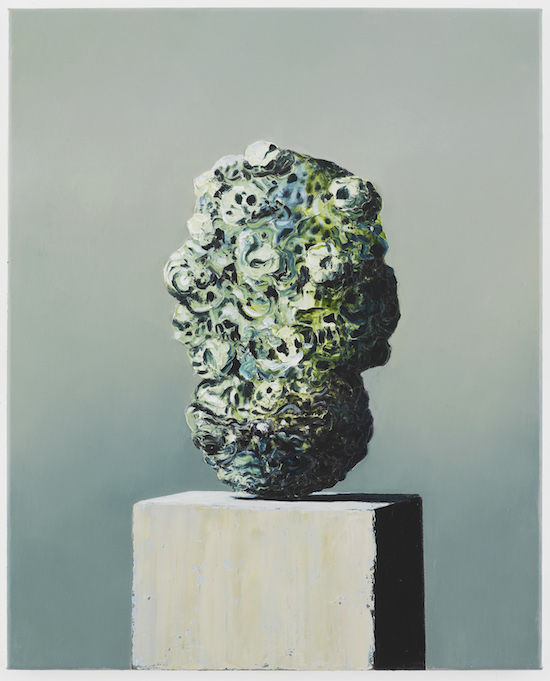

Ivan Seal, adultery bi prenontspliver, 2015

Memory. It’s a funny old thing. And for Berlin-based artist Ivan Seal, memory isn’t only funny – you can throw in beguiling, banal, totally enthralling and infinitely alluring while you’re at it. That’s because it’s this central subject of memory that underlines Seal’s ‘endless alphabet’, a series of paintings – imagined scenes and remembered objects made using no reference materials except for his own grey matter, and the canvases themselves – in a project spanning over six years, with no signs of fading like the neurons that imagined them.

With this style and method, Seal has struck deep into a vein of psychological, nigh on neuro-exploratory art, an intersection where figurative and abstract combine and bloom out like a billowing mushroom cloud of possibility and meaning. But to attempt to explain or classify his work would kind of miss the point.

I first came to Seal through his collaboration with fellow Stockport export, the experimental electronic producer and underground darts maestro Leyland James Kirby (a.k.a. V/Vm), creating the artwork for the latter’s Caretaker project – itself a study of memory and the effects of dementia.

The mysterious hunk of clay, with its single baffling matchstick, sat on the sleeve of An Empty Bliss Beyond This World compelled me to seek him out. And discovering that he’s down the road from me on this now foreign continent (a long-ish road, given), we ducked into a café to discuss where this all grew from.

Over a cortado he settles into the weighty Chesterfield, a kind of fizzing energy coming off him – not just from the coffee. We’re only 1pm and he says he’s already completed a painting today, and worked on several others.

The conversation soon branches out, like one of his paintings, taking in everything from D&D to teaching at the Royal College of Art – in fact, I feel like I get so much material that I completely forget my laptop on the café table, only realising what I’ve done three U-Bahn stops away in a total panic. By the time I’ve switched platforms and sprinted back, cursing (almost crying, if I’m honest) into my elbow bends that it’s happened again, £1,000 dropped, I find the table occupied only by a young German family sharing creamy cakes. The staff haven’t seen it either. It’s gone. Very quickly one of my dream interviews becomes a nightmare.

Short film, ‘darken the circle please remain seated for the hike’, 2018 – inspired by and featuring audio works by Ivan Seal. Shot in Berlin by Declan Tan

I think back through the interview. I remember pointing out early that, in terms of subject matter, we’ve had some overlapping interests. I mention that I caught one of his online video interviews, in which he begins proceedings by discussing LSD and ecstasy, apropos of very little. It seems a good a place as any to kick us off. It occurs to me that the mystifying aspect of Seal’s work might stem from that percolation of substances into his often-surreal painted dramas. I dig right in with a favourite Kubrick quote to see where he stands: “Drugs are basically of more use to the audience than to the artist.”

“When you get into your own thing,” he says “then you realise that that can give you a deeper, longer and more frustrating hit. Imagine taking something which has a highly addictive property in it – which for me is making art. It’s something which is not maybe the wisest of life choices – but you keep coming back to it. I didn’t paint for years and then I started painting again when I was 31 or something, and in that found the addiction again. I had that before but gave up painting – for the wrong reasons, I think.”

It was his Sheffield art college tutor Steve Dutton who suggested artists can tackle the problems within painting with any medium. “It doesn’t actually have to be paint. And I still believe in that.” Venturing into installation and then sound, it took Seal ten years to return to the canvas. “I see it as a journey to get back to a moment where you ask yourself, what do you actually want to do? But I think that moment needs working towards and it took a long time, to ask what action has the promise of satisfaction somewhere in it? And I thought the last time that happened was when I used to paint. So I started painting again.”

But he found that painting re-uptake somewhat inhibited. For about four years, he found himself painting over paintings, again and again. “I had about ten paintings, and they’d all be ten not-so-great paintings. But it was more about opening that doorway and slowly getting in – because I didn’t know what to paint.

“Over-painting and over-painting and over-painting – it all felt very academic in a way. Then I was advised to just get a lot of canvases or paper, and just do a lot, rather than try to make some bloody masterpiece. That’s advice you give students when you notice they’re constantly polishing a turd, and it happened to me.” Arriving at this moment himself, Seal had an epiphany. “That’s when I first kind of came to this idea of the disaster, the catastrophe which is inherent in a blank canvas, blank page, or a blank file in front of you. You’re only going to ruin it, but for some reason you have this urge to ruin and you start with that.”

Ivan Seal, allchav tart, 2016

For Seal, the whole activity of painting is entangled with a notion of failure – “a notion of struggle. And struggling with your own failings until something works. I don’t paint from photographs or objects. I constantly return to that moment of blank canvas and ruining it, and coping with it.”

For the first piece of this series, he wanted to paint something: not somewhere, not someone, “because I wanted the somewhere and the someone to be in something. Then I thought, then I’ll paint something that’s kind of nothing, in a way.”

He had been reading a story called The Golem. “It’s this idea that comes from Jewish fables. You have this lump and you form it into a little person and it does things for you. But if it doesn’t have this sticker on its forehead – which I think translated is ‘truth’ – then it just does its own will. And for me, this notion you have something, you create something, but it’ll in turn to attack you and destroy you, seemed very apt to painting.”

It must have been hard to predict how that base material, painted on canvas, would transform into an unending project. “Clay is where a lot of art comes from, a very basic form. I knew I wanted to paint a lump of black clay, but I didn’t want it to be somewhere that was ‘located’. In art, you put things on plinths, like a stage – so I put literally a lump of clay on a plinth in paint. Then I painted a match in it. Suddenly I had drama. And I’ve been working on that series since. In some senses, the action is utterly banal, and the intent is absolutely banal, but there’s the same point which holds, I feel, countless opportunities for somebody to look at it, and for somebody to interpret.”

Now Seal produces this work at an astonishing rate. “Some of them are very small,” he says, now upstairs in the studio, “then other ones I could be working on for like a year. Constantly going back to them.”

This approach means he has twenty or more canvases on the go at any one time, spread across two rooms in what used to be his apartment. They’re stacked up by the dozen in a storage room. The only noticeable piece not by his own hand is a painting of a bridge and town by his grandfather, a source of inspiration for many of his colours, Seal says.

“Rather than having one singular moment, painting like this works more like a brain,” he says as we stroll across the bare floorboards. “It works more like how you think. The studio somehow becomes an active way of thinking, a big head which I’m stepping into every day and basically poking around, like your own head works when you’re thinking about stuff.” He pauses.

“You can’t trust any memories at all, can you? Because it’s all glitched. It’s all nonsense in a way.”

Ivan Seal, the pot complains, 2016

Painting in this way is a meandering thought process, “but whilst moving your hand – and it’s somehow about making this distance between your hand and the head as short as possible.

“That’s what I’ve always loved about improvised music, the immediacy. It’s not people dicking about, it’s just thinking on a really hyper-fast level. Each move is very quick, it’s not like I’m executing tiny bits, and it’s very laboured.” He crouches down and picks roughly at the paint as if to illustrate his point.

“But I’m shifting paint around as well, taking paint off, putting it on, taking it off again. Then you often look at the paintings – and you don’t get this if you look at them online – if you see them physically, the paintings have a lot of scars on them, all over. You can see bits where something else was there, and I’ve just worked through. Instead of trying to illustrate something, I wanted the actual action of painting to be ‘it’.”

“It’s like you concentrate on one thing and you’ve got all this other information coming in,” he continues, “and that stains it. That alters the taste of it, recreates it – like that notion of glitch. They create errors in it. These painted objects are like a sum of these errors and glitches and that’s why there’s a hell of a lot of thick overpainting of things. A lot of the time I’ll start with something and then start layering paint on to cover up my tracks, or to cover up something too personal. Because that’s what we do.”

Ivan Seal, auxch noise reduced, 2016

For the last half a decade or more, he’s been evolving this idea that the action of painting becomes very close to the errors of how we think, or how you remember something – a kind of psychology of painting. “I always have to be careful,” he says. “When you talk about memory, people always think of the romantic idea. But memory is also the memory of meeting you now, or the memory of the Apotheke front window I saw this morning, with these horrible straw faces in. But each time the memory is glitched.”

“If you put the original event next to the memory, they’d be totally different. And I love this noise in-between, what you’ve gone through, your life. And trying to put it down somehow, or trick time somehow by activating it, and I find this noise, this glitch, has countless potentials and paintings in it.”

“Art is always working from memory,” he says. “It’s all questions of – even if you’re painting from something directly in front of you – it’s about that distance to inside you and then out. Like a loop. It’s about what you can do with that and how you pervert it.”

The son of a butcher and a ballroom dancer, Seal finds there are subjects and figures he naturally returns to, as a way of understanding them. His dramas are now more likely to be populated with gesturing porcelain figurines and mysterious, metamorphosing clays transforming like waking dreams from one form into another, as if consuming themselves.

“I don’t want to paint them but I do,” he says of the porcelain pieces – like dusty abandoned objects on some wooden-veneered, fat-back cathode ray TV from the 80s. “And they’re personal things. I can understand them, but they’re more like starting points. The dancers in my paintings are often like that, something I’m familiar with and just somehow know or have a warming to – and that’s the vehicle to get to other things.”

Ivan Seal, syntaksipolontian klapis, 2015

At several points in the conversation, like this, Seal drops a register and explains candidly his suspicion of painting, and of painters. It’s clear he takes his work seriously, but not this romantic ideal of ‘the artist’.

“Images are constantly telling us how to think. If you create, you’re involved in something which rather than saying ‘think this’, you can say ‘think with’. Then the process of looking at the work, I hope, is close to the process of making it. Because it’s just something to use and then to make your own sense of, in the context of your own life and your own memories, and everything which went from being born to being stood right in front of it. All that comes into it, so why not use it.

“As soon as you look at a painting, you’re decoding. But the actual decoding becomes something which becomes immersive. But I don’t want it to be ambient. I have a problem with that ‘drugginess’ of ambience and this ‘letting go’. I want the paintings still to be active. Like this thing that this collaborative outfit Farmers Manual said once: you’re building something to a certain point until you cease to be the makers and you become the audience. That’s how I see the painting, as soon as I get to that point when I’m pushed out as the artist, the maker, that romantic idea, and suddenly I’m just back into being, looking, thinking: ‘Who the hell are you?’ That’s when I know it’s hit on something that it shouldn’t have, and it’s good to go out the door.”

Short film, ‘Svarte: Ivan come down take it easy’, 2018 – inspired by and featuring audio works by Ivan Seal. Shot in Berlin by Declan Tan

I ask him about his rough handling of the canvas as he crouches down and peels something off a corner. “I don’t think you can ruin a painting,” he laughs, looking up. “There’s always opportunity for them. Even if you’ve terrorised it, or you think you’ve destroyed it, it’s just another opportunity. It’s just another thing to improvise with.”

You’ve never destroyed a canvas? “No, I don’t destroy canvases. I often get to a point where it’s terrible, and then something very quick can happen and you finish it within a couple of hours.” He stands: “Someone asked Philip Gusten, how do you know when a painting’s finished? He said, ‘It stops staring at me.’ And there’s something in that. Work is something you just know.

“Often one talks about truth of material in arts. They say if you make a sculpture out of clay then you have a truth to material, it has all these thumb prints and how the material actually works. But with painting, the truth of the material is its lies. It’s a lying thing. It says ‘I’m this’, but it isn’t.”

He segues quickly into ‘making art’ versus ‘showing art’. “Those are two very different things,” according to Seal. “You can have your reasons to make art, but you’ve got to have your reasons to show art. For me, that was about creating an opportunity where people can all leap, with just this thing on the wall. I like its economy of means. I like that it’s minimal in a way.”

Economy of means. The words ring in my ears. Back to that laptop, now three stops from the café and counting. I think to call up Ivan and ask if he saw the Macbook. I think no, actually, that’s not a good way to end an interview. Now I see my wife’s face in my mind’s eye. She will fully murder me, I’m convinced (I left another one on a bus in Leipzig only six months ago).

It takes a further thirty minutes of cursing into my elbows and at my shoes stood on the now-rush hour U-Bahn to get back to the flat, as the hope of the silver flaps still charging somewhere at home quickens my crepe soles across the dusk snow-slush. I try to grasp firmly onto the memory of it in the café but each time the laptop slips away, the train carriage glitches. Was it ever there? How did I just walk off, leaving it behind? How did I get so swept up in the discussion. Easily, I think. It’s a price to pay for the interview. It’s fine.

I charge into the living room, and there it is. Full battery.

Memory. It’s a fucked, banal, funny old thing.