In a promotional video for the Talking Heads concert film Stop Making Sense, David Byrne – playing several different characters – interviews a version of himself while wearing his now iconic ‘big suit’. Asking himself about whether he writes love songs, Byrne responds, “I try to write about small things. Paper, animals, a house… Love is kind of big.” This obsession with the minutiae of human existence, and a rejection of typical song subjects, is one that Byrne has pursued for the majority of his long career.

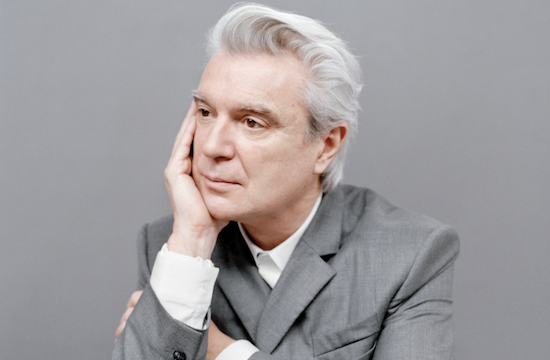

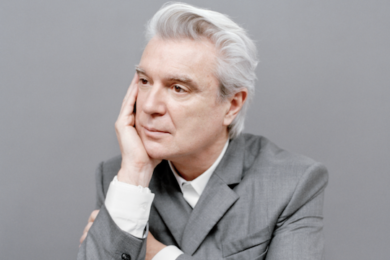

Byrne, alongside Tina Weymouth and Chris Frantz (and later, Jerry Harrison), formed Talking Heads in 1975 and became enmeshed with the 1970s New York punk scene, becoming one of the most influential and important groups of the 1980s and beyond. The band’s art school roots set them conceptually apart from their contemporaries, the likes of which featured Blondie, Television and Ramones. Although Talking Heads were very much ‘a band’, with exceptional contributions from all four core members and an impressive list of outside collaborators, the bedrock of the band’s vision was largely built on the ambitions and persona of David Byrne. Pop music had yet to really encounter a character like Byrne’s, and thus his alienated, idiosyncratic worldview helped create some of the most radical and exciting pop music ever made.

As tensions between members took hold over the course of their eight studio albums, Talking Heads slowly fell apart, leaving Byrne to spread his wings into many other areas, including film, theatre, installation art, and writing. Despite this broad output, Byrne could never really be accused of dabbling, as he’s proven to make both enlightening and incredibly successful work across all of these areas – always driven by a genuine curiosity and a need to take apart, and understand, the subjects he looks at.

As he’s aged, his persona has became less jangled and reactionary, and he and his work have become more warm, inviting and good-natured. Throughout, Byrne has mastered the art of taking complex subjects and representing them in simple and effective ways. Often, by exploring them as if he were an alien visiting from another planet. It’s easy to imagine Byrne slowly floating over the world, listing the things that he sees and what he thinks about them, as he does in ‘The Big Country’ by Talking Heads.

These analytical lyrical perspectives are what colour Byrne’s best songs and work in general. Establishing himself as a person who may have been looking at the same vista or painting as you, but was actually stood a few feet over to the other side, and much closer, telling you what he saw there instead.

Due to the sheer volume of great work he’s made, the following list is a mixture of both landmark and less-examined contributions throughout his long and varied career. There are some notable omissions, including the first two Talking Heads albums, 77 and More Songs About Buildings And Food, commercial highlight Speaking In Tongues, and Stop Making Sense – widely considered to be the greatest concert film ever made. These things, while brilliant, have been covered extensively in other places, including on this very site. The list instead focuses on Byrne’s personal contribution to the Talking Heads albums, and includes highlights from across his array of excellent solo material and collaborative work.

Talking Heads – Fear of Music (1979)

There’s an idea that the title Fear Of Music may not describe melophobia, but that the album is a soundtrack to many various fears, if one was to substitute ‘Music’ for any of the one-word song titles on the album i.e. ‘Fear Of Cities’, ‘Fear Of Paper’, ‘Fear Of Heaven’ etc. Most of Byrne’s lyrics stay true to this concept by approaching their subjects with extreme paranoia and a suspicion of their influence or intent. “What is happening to my skin? Where is that protection that I needed? Air can hurt you too,” Byrne sings on ‘Air’. Or, as he growls on ‘Animals’, “Animals want to change my life, I will ignore animals’ advice!”

While similar observations make up the majority of the previous two Talking Heads albums, they first felt truly realised on Fear Of Music. What feels uniquely Byrneian about them is that they rarely generated any feelings of sympathy toward the character assumed, and there’s a detachment to the delivery that doesn’t suggest they’re autobiographical either. In fact, a lot of the lyrics on Fear Of Music are plain hilarious when coupled with Byrne’s delivery, such as the passive-aggressive questioning of, “Drugs won’t change you. Religion won’t change you. What’s the matter with you?” from ‘Mind’.

Of course, there’s nothing inherently funny about these words, or any others on the album, but it’s the kind of displacement of emotion and lack of authenticity that Byrne is adept at, and makes the listener relate to the words in a way that feels antithetical to pop music’s penchant for sincerity – something we could probably do with a helping of in 2018.

Byrne’s jittery outlook on Fear Of Music also introduces a character he embodied for the near-entirety of Talking Heads’ career, the kind that appears in the video for ‘Once In A Lifetime’ , and the persona that gradually surfaces as Stop Making Sense progresses. A sweaty, overworked modern man in the capitalist machine, equally troubled by, and cautious of, all the objects and cultural signifiers that he needs to make decisions about, so that he may appear as a functioning member of society.

David Byrne & Brian Eno – My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts (Recorded 1979, Released 1981)

Continuing their collaboration from Talking Heads, Byrne and producer Brian Eno, realising they shared similar philosophies and record collections, decided their relationship could be fruitful beyond artist and producer. Using two tape machines at once, the pair set about gluing together music that incorporated samples of Christian evangelists, exorcists, Lebanese mountain singing, and AM talk radio.

The resulting record is a strange music originally intended to be the sound of a non-existent, perhaps futuristic culture, with the processed vocal samples as the lead instrument, funk basslines and eminently danceable rhythms fuse within a patchwork of electronics and shrill guitars. There’s something urgent and radical in this sound that defies its origins in the late 70s too, not least because of a lack of technology around at the time to support something so technically difficult.

It’s hard to take this album entirely at face value, however, when its pioneering creative approach has been so comprehensively mythologised. Despite The Bomb Squad’s Hank Shocklee citing it as a touchstone for their collage-like approach to making music, to say that it pioneered the technology and culture around sampling would be hasty, but this assessment is often repeated when exploring the record’s mythos. Also, due to its extensive sampling of, mainly, Arabic vocal music, and its rhythmic foundations often strongly indebted to West Africa, it’s worth considering this record as part of a conversation around cultural appropriation too, especially now there’s a wider social discussion about this issue that was not as developed when the record was made.

Many listeners may find it indefensible because of this. It has, however, been an important record for introducing these sounds to western audiences, and facilitating later music inspired by the original artists. It’s a brilliant record, too, and it established David Byrne the collaborator – outside of Talking Heads – a precedent for the breadth of ideas to be explored in his later work.

Talking Heads – Remain In Light (1980)

Is Remain In Light the greatest album of all time? It would obviously be impossible and a little insane to answer this question definitively, about any album. But if you asked me during any of the thousands of times I’ve listened to it, I would probably say yes without hesitation. If you had asked my curious teenage self, hearing it for the first time while riding my bike to school, and being so bowled over that I nearly fell off, I’d have said yes then too. That same thrill of listening hasn’t ever diminished for me, and I doubt it has for anyone who loved it upon its release either. I just got up and danced over to the other side of the room to it while writing this and I somehow felt like I’d had a completely new experience with it. How many records truly do that for you?

The pace and ambition of the first half of the record is especially mind-bending, and it demands your body and brain to react in unison. This time, there is no unifying principle, and Byrne’s words ask more questions than they answer, leaving you constantly on the brink of resolution, much like the music beneath them. Water flowing underground.

The music – polyrhythmic, angular and driving – was constructed from hours of jams that the band recorded, and that later Byrne and Eno made loops from, inviting the likes of Adrian Belew and Jon Hassell to contribute their unique playing styles as overdubs. Surrendering to this improvisation and eschewing common songwriting techniques, Byrne was forced to think abstractly about his words and vocals. As though replacing the space that the samples occupied on Bush Of Ghosts, here Byrne mimics their cut-up fragments in real time, to most notable effect on ‘Once In A Lifetime’, one of the greatest pop songs ever released.

Talking Heads – True Stories (1986)

After three albums of outward-looking, culturally hybridised music, Byrne’s gaze turned slowly back to America and to the themes that run through the first two Talking Heads albums. After the band reached their commercial peak with Speaking In Tongues, and received widespread acclaim for the groundbreaking Stop Making Sense, Byrne had the freedom, creatively and financially, to explore any avenue that interested him. Making a film of his own doesn’t feel like a huge sideways step, since Talking Heads were such a visual group – the way they presented themselves was always carefully planned, from what they wore, to album artwork and music videos.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the creative freedom Byrne was afforded in making True Stories makes for a very offbeat picture. Set in the fictional Texas town of Virgil, the film is a series of vignettes of its residents, and an insight into their lives while preparing for ‘The Celebration Of Specialness’, an event marking the 150th anniversary of the town. Many of the scenarios the characters find themselves in were adapted from tabloid newspaper stories Byrne collected and made drawings of while travelling the US on tour, giving the film its title.

Starring John Goodman, Spalding Gray and Byrne himself, the film is a musical of sorts, with lots of the sequences accompanied by an original Talking Heads soundtrack, though in the film it was mostly sung by the cast. Byrne assumes the role of narrator, and his observations are typically Byrneian. Continuing his penchant for extraterrestrial-like curiosity, Byrne approaches this group of oddballs and small-town strangeness with total fascination. Rather than a sneering portrait of weird America, though, True Stories has a great fondness to it. You’re behind the characters all the way – right up to John Goodman nailing ‘People Like Us’ in the genuinely emotional climax.

True Stories feels like the perfect extension of Byrne’s lyrical practice up to this point. It ends with this touching monologue from his character, which seems to sum up a lot of his work:

“I really enjoy forgetting. When I first come to a place, I notice all the little details. I notice the way the sky looks, the color of white paper, the way people walk, doorknobs, everything. Then I get used to the place, and I don’t notice those things anymore. So only by forgetting can I see the place again, as it really is.”

David Byrne – Rei Momo (1989)

In 1988, Byrne founded Luaka Bop, a label he set up via Warner Bros. to release his solo material, alongside other artists and compilations of – what is problematically known as – ‘World Music’ (Byrne goes into more depth of his dislike of this term in a New York Times article published in 1999).

The first compilation from the label, Brazil Classics 1 released in 1989, features a number of Brazilian artists making music in a range of styles, compiled by Byrne himself. This fascination with Brazilian music – and, further, Afro-Cuban and Afro-Hispanic song styles – informed the direction of Rei Momo, the first release under his own name outside of Talking Heads. (The band itself was now dead in the water, allegedly unbeknown to the other three members, after releasing their final album Naked and having not toured in five years.)

Rei Momo was a strong beginning to a very fruitful solo career, though one that arguably took a while to reach the quality exhibited here. It’s a thrilling exploration into Latin music and sensibilities, with Byrne, rather than simply appropriating, often working closely with noted Latin American musicians and vocalists, eventually touring with them as a large ensemble.

Though the rhythmic and harmonic framework feels like a study of the styles on display here – all of which are credited as a subtitle for each song – the songs themselves are a further development of Byrne’s at times surreal depictions of American life and the interactions of humans.

David Byrne – The Forest(1991)

Although Byrne was, by 1991, no stranger to composing for theatre and dance projects (see: The Catherine Wheel and The Knee Plays), The Forest, a collaboration with experimental theatre director Robert Wilson, feels like a curveball in his career, though one that expanded his palate even further. Filled to the brim with sweeping, romantic orchestration and wordless vocalisations, the piece transplanted the themes of the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, a flood myth, onto the events of the Industrial Revolution, an idea that the archetypes of ancient mythology are simply narratives we keep repeating.

For someone who had been working deeply in the realms of rock music and cross-cultural rhythmic studies for nearly two decades at this point, The Forest is a remarkably accomplished set of orchestral music, and stands up very well on its own, even without Robert Wilson’s typically elaborate staging. So in-depth was Byrne’s work on this score that it also seems to be infused with a genuine emotional resonance and empathy that rarely felt present on Talking Heads records. The short bit of text that accompanies The Forest, re-published on his website, hints at a certain emotional awakening in Byrne, and a close consideration of our place in the world, one that, upon reading now, feels timely once again.

David Byrne –Look Into The Eyeball (2001)

I’m probably of the last generation of people in England not to have had computer technology normalised into reality from birth, so I can still remember walking down the aisles of beige towers and bulky CRT monitors in a PC World at a Bournemouth retail park circa 2001, in awe of what might be possible. You might not remember, but bundled with Windows XP’s Media Player was some sample music. There was a piece by Beethoven, and there was also a new song by David Byrne, called ‘Like Humans Do’. While I can’t say if I understood enough to enjoy the piece at the time, it certainly left a big impression on me, enough to keep me pressing play on as many machines as possible, creating a weird Steve Reich-like symphony of out-of-sync Byrnes singing “For millions of years, in millions of homes”.

This retail park experience feels like a strangely preternatural way to introduce Byrne’s presence into your life. For Byrne, ever close to the cutting edge, being bundled with one of the most widely distributed pieces of software ever is not only a genius marketing move, but the song itself is fitting too. The lyrics reflect how there’s nothing really banal about what we do as humans and that everything should be celebrated, whether it’s breathing, eating, laughing, loving ourselves, or, in my family’s case, buying a computer, especially at a time when the technology was becoming better designed and more accessible. It doesn’t feel like an accidental choice of song in this sense.

The rest of Look Into The Eyeball wouldn’t reveal itself to me until much later on in my teens, but it’s a joyous and unpretentious album, featuring some of the most delightfully straightforward lyrics and song structures of Byrne’s career. There’s still a heavy emphasis on rhythm and melody, but this time embellished with lavish string arrangements and processed drum patterns. Since the most interesting work Byrne made in the 90s was largely not what was featured on his albums of songs, Look Into The Eyeball was a refreshing return to simplicity. And, in contrast to his anxious younger self, it radiates an optimism that has followed his work and persona ever since.

Playing The Building Installation (2005)

You’re probably starting to get the picture now, if you didn’t already know, that David Byrne likes to work in a lot of different fields, and seems to be pretty good at doing so as well. That he views things slightly differently to the rest of us, and how that forms a central pillar to his work, especially in this situation, where Byrne viewed the blank canvas of a building not just as a collation of building materials, but as a space that had its own timbral qualities to be eked out of it.

Established first at Färgfabriken in Stockholm, later at the Battery Maritime Museum in New York, and finally at London’s Roundhouse, Playing The Building consisted of an old pump organ chassis hooked up to machines that were in turn attached to the infrastructure of the building – metal beams, pillars, and heating and water pipes. These parts of the building are struck, or air is blown through them, when someone presses a key of the pump organ that they’re connected to, turning the building into a musical instrument.

Much like a similar installation of Byrne’s where the audience were invited to walk over a carpet of guitar pedals, altering the sound as they did so, Byrne’s installation works often require audience participation to function and have value instilled in them. These simple ideas are extremely fun, and there’s plenty of good footage of people playing them online. They’re also ways of Byrne further exploring people’s relationship to the world around them, with a playful and childlike wonder.

How Music Works (2012)

In 2010, Byrne gave a TED talk called “How Architecture Helped Music Evolve”. He spoke about a range of music venues, from CBGB to Wagner’s opera house, and how music was written to fit these spaces. Byrne spoke of the very linear idea in pop music, which dictates that as the band progresses, they play bigger venues due to demand, and thus their music takes on a grander, more reverberant feel to fit those spaces. Byrne noticed that, as he grew more popular and played bigger venues, the intricate rhythmic aspects of his music would be lost in larger acoustic spaces with longer reverberations, and so perhaps this market-driven, progressional ideal of music can ignore the music’s philosophical or intended contexts. These observations are the kind that would become chapter-length analyses in Byrne’s book How Music Works.

The book uses Byrne’s personal journey through music as a way of discussing things like how technology has helped shape the experience and distribution of music, how business factors have slowly diminished traditional media’s influence over audiences, and the new ways of curation and dissemination that exist as a result. It’s a fairly comprehensive look at a very broad subject, but written in Byrne’s conversational style, rather than an overly academic one. Likely due to the accessibility of its prose, and Byrne’s palpable enthusiasm to take his artform apart from many angles, the book was a huge hit. And rightly so.

David Byrne – American Utopia (2018)

Byrne’s latest studio offering – his first solo release in 14 years – brings with it a host of timely ideas and useful concepts. Thematically, the record is tied to a series of lectures, events, and a kind of online scrapbook called Reasons To Be Cheerful – Byrne’s attempt to reverse the tone that our doom-laden media has taken on, and challenge the general perception of the absolute state humanity has found itself in.

Reasons To Be Cheerful shines a light on positive initiatives, politics and happenings that give us a reason to find hope in the face of something seemingly irrevocable. Focusing on topics such as civic engagement, climate, economics, education and science. “Wind Sustainable Power Is Becoming Financially Profitable” is a recent headline on the site, and there is an emphasis on the gathering of people in physical spaces, and the great things that can occur when that happens. It’s a noble sentiment and a refreshing perspective at a time when a lot of art and discourse is – arguably justifiably – focussing on dread and dystopia.

The associated album, American Utopia, reasserts Byrne’s relevance in a contemporary context, as it’s the first time in a while that he’s produced something as conventional as an album, especially one so wonderful and remarkably succinct. The lyrics, while not tackling the above subjects head-on per se, tend to give a more oblique perspective on humanity’s current predicament. Byrne even allows room for musings on what animals might be thinking of us humans as we hurtle towards extinction, a real u-turn from the Byrne who was “ignoring” animals’ advice on Fear Of Music.

Recruiting a host of younger musicians, including Sampha, Happa, and Isaiah Barr of Onyx Collective, helps imbue the songs with a fresh vitality, as does the excellent production work by Rodaidh MacDonald, and the mix-wizardry of alternative pop music’s hired gun, David Wrench. Elsewhere, Oneohtrix Point Never contributes his trademark sonic sculptures in some of the album’s darker moments, as on standout ‘This Is That’.

The tour for the record starts in late March 2018. Byrne claims it is “the most ambitious show since the shows that were filmed for Stop Making Sense,” promising to free his band from the constraints of stands and cables, giving them totally free movement across the stage. Given the success of Byrne’s progressively choreographed sets over the last decade, it’s a hugely exciting prospect. It’s a testament to Byrne’s relentlessly artistic spirit that, even now at the age of 65, he continues to have the capacity to thrill us.

American Utopia is released via Nonesuch on March 9. David Byrne headlines Roskilde Festival on Friday 6 July