We live in an artistic climate where it seems that pretty much anything can and will be eventually reassessed and rehabilitated. Scenes which were written off first time around – gabba, happy hardcore, Oi! – will eventually be re-examined and found to contain hidden depths, or to have caused a ripple which led years later to something significant.

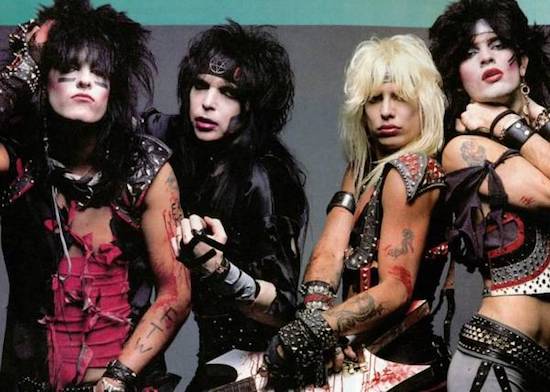

However, one genre seems to have proven remarkably resilient to any of this rediscovery – the glam metal that dominated the pages of Kerrang! and filled shows like MTV’s Headbanger’s Ball from the early-mid 1980s. It arguably began with Motley Crue’s 1983 LP Shout At The Devil, the first full album which not only sounded but also looked like glam metal. It lasted until 1991, when the combined forces of grunge’s emergence and the tired excess larded over both volumes of Guns n’ Roses’ Use Your Illusion performed the cultural equivalent of an asteroid strike on the genre. While the parameters weren’t quite that cleanly drawn, popular memory records that the likes of Poison, Warrant, Dokken, Skid Row and LA Guns were trapped firmly on the wrong side of the divide as music’s tectonic plates moved, and were as outmoded and beyond redemption as the worst kind of prog outfit after Spiral Scratch.

For all its outsider posturing, glam metal was commercially enormous – when U2 were number one on the American album charts in 1987 with The Joshua Tree, the following five chart places were occupied in sequence by Whitesnake, Motley Crue, Bon Jovi, Poison and Ozzy Osbourne. These acts helped grow MTV’s popularity and broke ground for touring US bands everywhere from the far east to the Eastern Bloc. While purists would regard ‘real’ glam as being limited to the sleazy scene around LA club The Rainbow, Gazzarri’s and other Sunset Strip venues, its halo effect served to reboot 70s groups in its image, with Heart, Whitesnake and Aerosmith all successfully restarting their careers as polished, hit-making hair-bands.

What afterlife glam metal has had has largely been as a joke of sorts. Spoof metallers Steel Panther recently played a sizeable UK tour; club nights like Ultimate Power celebrate the softer end of the genre with a nod and a wink. It’s also been tinged with a pitying element of jesus-look-at-this-exercise-in-futility, as seen in the award-winning documentary Anvil: The Story of Anvil. Beyond a couple of memoirs (Seb Hunter’s glorious Hell Bent For Leather and Chuck Klosterman’s Fargo Rock City), music’s serious and high-minded critics have mysteriously failed to engage with the possible subtexts present in Ratt’s Out Of The Cellar. For fans of the genre, the wholesale scrapping of a vast body of work was neatly captured in one scene from Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler, where Mickey Rourke’s nostalgic protagonist – Randy ‘The Ram’ Robinson – props up a bar with his girlfriend, bemoaning the cultural shifts that had befallen his tastes:

Randy: Then that Cobain pussy had to come around and ruin it all.

Cassidy: Like there’s something wrong with just wanting to have a good time?

Randy: I’ll tell you somethin’– I hate the fuckin’ 90s.

The millions of fans who propelled these records up the charts, filled stadia and walked around suburban market towns in massive white trainers and spray-on jeans largely went quiet through that decade, their previous endorsement denied and willfully misremembered. Glam metal effectively became music’s equivalent of the Iraq War. It remains about as critically popular at the time of writing.

The case against glam metal is easy enough to build: Bon Jovi were clearly inauthentic pop hacks who had never done a day’s unionised labour in the docks of New Jersey in their lives. Bands like Warrant traded in a sort of horny, willful stupidity which hasn’t aged brilliantly in the current moral climate. Sartorially, it’s always going to be easy to mock a man wearing a top hat or – in the case of Odin frontman Randy ‘O’ – a pair of arseless leather chaps. But taken individually, these judgments seem less like bugs and more like features: most of our greatest pop stars have played fast and loose with character and identity; plenty of ‘dumb’ music from garage punk to Chicago house has been utterly transcendent. You can argue that in its glorification of ugly men in make-up and willfully provocative outfits, glam metal was heir to the same impulse that drove its British namesake a decade earlier – Def Leppard’s Joe Elliot is an obsessive fan of British glam, while W.A.S.P. frontman Blackie Lawless had cycled through a series of tail-end glam rock bands like Killer Kane and Circus before striking metal paydirt in the 80s.

But even if this still leaves you cold – and if you fundamentally regard Skid Row’s ‘Big Guns’ as a bit of retrograde sexist rubbish rather than a screeching thug-pop classic then, I suppose, fair enough – what I think is harder to dispute is that glam metal was part of something bigger both within music and within society at large that warrants inspection. Firstly, the music: with its ragbag of influences including stadium rock, vaudeville, campy drag, cowboy blues, train songs, the confrontational shock of punk and glam, glam metal functioned as a pile up at the end of 40 years of white guitar music. It made for a final point before everything turned inwards into self-reference and irony. The recent comparison point may be with EDM, and its smash-and-grab approach to the decades of club music which have gone before (In a 2012 review of a Skrillex show in London, John Calvert wrote in The Quietus of how "the impression given is an awe-inspiring consolidation of years of post-rave party music. Every known cheapjack event from every known sub-genre is co-opted and redeployed at a dazzling rate of frequency."). Secondly, the 1980s was a decade in which America superficially regained its confidence and Reagan’s boast that "It’s morning in America again" underwrote a series of bigger, more pumped and hyped spectacles everywhere from action movies to art and advertising. With its air of artifice and supersized, steroidal performance, glam metal functioned as the musical wing of this project, before curdling into something bleaker and more introspective as the decade ended. In this reading, Axl Rose starting a riot in his stars and stripes cycling shorts was a generational equivalent of Jimi Hendrix drawing a line under the optimism of the 60s by reducing the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ to a feedback-drenched howl.

From this point, the idea of a wholesale rehabilitation of glam metal seems outlandish. But perhaps the stars are lining up in its favour. While there aren’t a surfeit of bands consciously apeing glam metal, odd echoing traces of it abound: to my ears, the processed, fizzing thump of much modern pop production doesn’t sound a world away from that which underpinned tracks like Vixen’s ‘Edge of A Broken Heart’. The recent reissue of Def Leppard’s Hysteria saw a surprising amount of grudging respect given to their painstakingly constructed sonic wall of bubblegum genius, while Taylor Swift and Mariah Carey both cover Def Leppard tracks in their live sets. WASP’s recently London shows were the biggest that they’ve done here in decades. It’s possible that glam metal is currently where disco was 15 years ago – something largely written off as the preserve of novelty retro nights and fancy dress, and broadly considered a joke by all but a diehard fanbase. That viewpoint seems ludicrous now, but was widely held – back then, Barry Gibb was being laughed off chat shows rather than feted at Glastonbury. Who knows – maybe we’re closer than we think to the point where the Pyramid Stage finally clears its schedule for Motley Crue, Ratt, Warrant, Dokken, Lita Ford, Skid Row and LA Guns to finally get their rightful credit and remind us, that there really is nothing wrong with just wanting to have a good time.

Justin Quirk’s book NOTHING BUT A GOOD TIME: THE SPECTACULAR RISE AND FALL OF GLAM METAL is crowdfunding now via Unbound. For more information and to pledge visit the Unbound website