By 1998 Radiohead had already built a reputation for releasing interesting and experimental music videos. With work by the likes of Jonathan Glazer (‘Street Spirit’, ‘Karma Police’) and Jamie Thraves (‘Just’), the band had become synonymous with videos that pushed technical as well as aesthetic boundaries; a formula that continues today through collaborations with Paul Thomas Anderson, Michel Gondry and others. While filming footage for his documentary, Meeting People Is Easy, director Grant Gee forged links with the group that would eventually result in one of their most famous videos: ‘No Surprises’. The fourth single from arguably their most acclaimed and successful album, OK Computer (1997), the video would cement Gee’s work with the band, leading to several more videos with them and their contemporaries. Twenty years after the single’s release on January 12, 1998, we spoke to Grant to find out about the video’s production two decades on.

The video for ‘No Surprises’ is listed on IMDb as your first film though it’s certainly not your first project. How did this video come about? And what was it that first linked you with Radiohead?

Grant Gee: In 1996 I made my first film – a thirty minute piece called Found Sound to accompany and promote an album of the same name by Spooky. I later found out that Thom Yorke was a fan of that album and that Radiohead had used tracks from it to bring them on stage for the OK Computer tour warm ups. Found Sound got me a meeting in early 1997 with Dilly Gent, the video commissioner at Parlophone.

Dilly had a plan to make a music video for every track on OK Computer, gave me a cassette of the unreleased album and asked if I’d write up ideas for any tracks I liked. I decided to pitch for ‘No Surprises’ and ‘Fitter Happier’. My idea for ‘No Surprises’ was very bad (some kind of sparkly, music-box themed, performance-based nonsense). The idea for ‘Fitter Happier’ was better (some kind of Martin Parr goes Ballardian reportage) and we were going to make the latter but I believe that the videos which were made for the first two singles (‘Paranoid Android’ and ‘Karma Police’) went hugely over budget and ate up over £300k of the money allocated to the video-for-every-track project. So it didn’t happen.

But there was still an idea to make some kind of film to accompany OK Computer and, I think as a kind of lower budget Plan B, in April 1997 I was asked to go to Barcelona and just document the album launch. This was three days of back-to-back interviews for the band and two concerts showcasing the tracks from the new album. They did it. I filmed it. I thought it was both wonderful and brain-damaging and managed to convince the band and record company to allow me to repeat filming at points throughout the world tour over the coming year.

Six months later in November 1997, Parlophone needed a video for the single, ‘No Surprises’, and didn’t like any of the ideas from the first round of submissions from prospective directors so, as I was around, they asked me if I wanted to have another go. This time I was on the inside of the machine and knew what was right.

What were your initial discussions for ideas of the video then? Was it your vision generally or did you discuss potential options with the band?

GG: There were no initial discussions. By that point the band already had the reputation of having excellent music videos made for them so it was just understood that as a director you could pitch anything you liked as long as it was excellent.

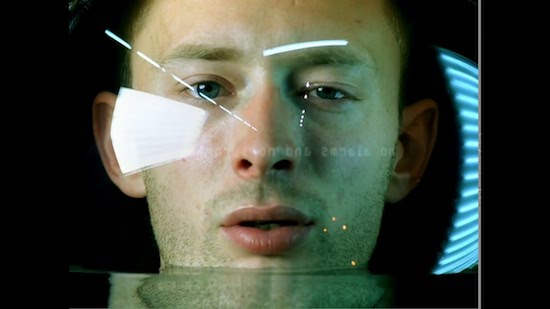

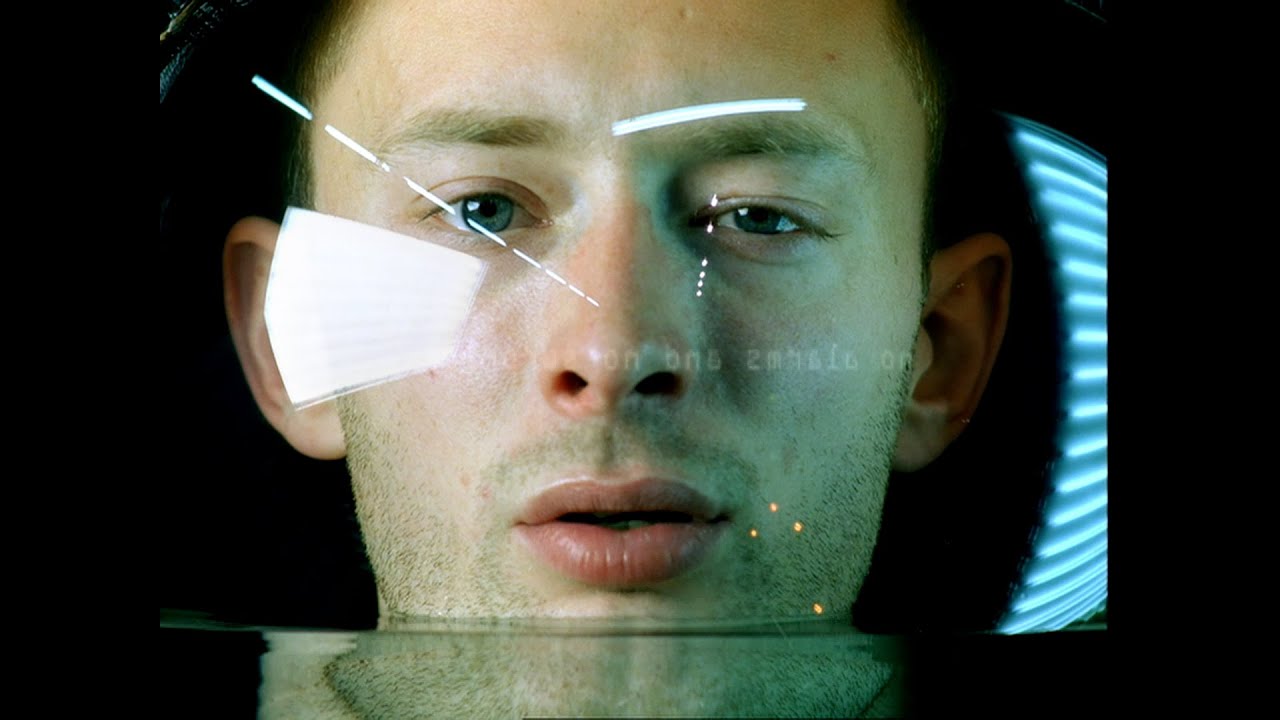

When it came to actually writing an idea it was ridiculously easy. I had a framed still from 2001: A Space Odyssey over my writing desk (the close up of David Bowman’s face inside his helmet at the moment when he realises Hal’s lost it). I listened to the track – zoomed into the line "…a job that slowly kills you" – looked at the picture on the wall in front of me and wondered if I could make a single close up shot of a man in a space helmet compelling for three and half minutes; remembering some anxiety provoking images from childhood television (a terrifying sub-Houdini underwater escape act on Blue Peter, the creepy alien blokes in UFO who had helmets full of green liquid…). I wrote a very precise moment-to-moment script for the video in about half an hour. Like I say, ridiculously easy and it has never happened like that before or since.

What made you consider shooting the video in one take?

GG: Again, the key lyric line for the video was "…a job that slowly kills you", so the task was to convey that feeling – of murderous seconds – as clearly as possible. Once I’d thought that the basic situation was the terror of rising water in an enclosed space then it was obvious that it would work best in real-time. It was more the idea of "real-time" than "one-shot" or "one-take."

How did you technically go about filming the video?

GG: The most important thing was that we had a decent budget – £80k – so were able to hire a proper special effects company who were able to design and prototype a custom helmet contraption which could pump water in slowly and steadily but drain it out in moments and reassure the record company that we wouldn’t drown their talent. There’s behind-the-scenes footage in Meeting People Is Easy that shows how it all looked but, in short, a Perspex semi-hemisphere with lots of pipes going in, drains coming out and a tight rubber seal around Thom’s neck that he could yank in an emergency.

From writing the treatment, I knew the moment in the track where the water should hit Thom’s lips – "…silent" – and where it should drain away again; "…such a pretty house". This meant that he would have to be fully submerged for about a minute and ten seconds. Thom was fine with this. He showed me how he could hold his breath for a minute and a half no problem. It still seemed a bit hairy though and felt like we really should try to keep it under a minute. The video’s producer, Phil Barnes, had a genius idea for how we could achieve this. He discovered that one of the Arriflex 35mm cameras (the 435, I think) had a motor, the running speed of which could be slaved to the pitch of an audio-sine wave. This allowed us to vary the speed of a section of ‘No Surprises’ for playback, ramp the camera speed to fifty frames a second for a short burst then ramp it back down to twenty-five frames a second and still have Thom’s vocals in synch for the end of the track. This saved us and Thom twenty seconds of submersion time.

All seemed fine initially. Come shoot day though, once Thom was rigged up and the lights were on with the crew standing by, action was called and playback started… Well, it was a very adrenalin-fuelled situation for the singer and adrenaline shortens the breath. Despite being able to hold his breath for a minute and a half no problem in stress-free conditions, on set Thom could only manage about five to ten seconds before having to initiate distressing emergency escape procedures. The day turned into a horror show. Again, the footage in the documentary shows exactly how it went: repeated torture.

It was only thanks to the American sport-coach techniques ("C’mon Tommy…let’s try fifteen seconds…you can do it kid…Now twenty, let’s go for twenty Tommy…") of the wonderful, now deceased Assistant Director, Barry Wasserman, that gradually, over the course of the day, allowed Thom to relax into his torture sufficiently to try for a whole take. We rolled and Thom did it. It was five minutes before the end of the shoot day and the (very expensive) crew went onto double-time rates. We did one more take and it wasn’t as good as the first one (Thom’s triumphal smirk as he comes though undrowned wasn’t quite as God-given).

We all went home having shot a total of about eight minutes of film during the day.

And how did this all tie in to Meeting People Is Easy as a documentary? Or was it entirely separate?

GG: It all felt part of the same world both in terms of the sci-fi tech world versus the individual imagery, and in terms of production; it was commissioned, financed, produced and approved by the same people.

Aside from the concert footage, the documentary was a close-up stare at the band reacting to a variety of uncomfortable, newfangled promotional situations, and a depiction of the newly globalising (just about to digitise) music business as a talent processing machine. The ‘No Surprises’ video is basically those ideas in promo form. I remember a queasy feeling before the shoot realising that no matter how the video worked out, the behind-the-scenes footage we would get would be great for the documentary and add some kind of meta-dimension to the thing. It got my hands properly dirty and stopped me from having any kind of feeling of observer superiority.

How then did ‘No Surprises’ link generally to what you wanted to do as a filmmaker with this relationship between the two projects working in symbiosis?

GG: I’m still fascinated by the simple documentary act of staring with a fixed camera for a fixed period of time at a single subject or situation and seeing what that stare and that time-span feels like on replay. Just the beauty and possibilities of that very basic cinematic unit.

The most direct link back to ‘No Surprises’ is possibly in the film I made in 2012 about W.G. Sebald’s The Rings Of Saturn (Patience: After Sebald). Even though the film is mostly shots of East Anglian landscapes, each shot is a twenty second fixed stare at a single feature. Twenty seconds because that’s the time the spring driven Bolex camera will run for on a single wind of the spring. The deadpan race-against-time feeling of the spring unwinding as the shot progressed feels to me related to the rise and fall of the water inside the helmet in ‘No Surprises’. Almost a materialisation of time and a sense of something inexorable and terminal. Patience was also the last project I shot on film and that sense of uncut again, a brief period of time being imprinted on an uncut strip of material, is important to both projects.