At first, Björk didn’t really understand why others saw her world as strange. “It’s so painful to hear that I’m a freak in people’s eyes,” she told Melody Maker’s Chris Roberts in 1987. “I am 21 years old and I have been fighting all my life for being looked at as normal. I am just normal to me.”

Over the years, with witless words such as “zany”, “wacky” and “kooky” always snapping at her heels, she became begrudgingly accustomed to her role as Empress of the Odd, and to people waiting, as she put it in 1997, “for antennae to pop out of your forehead." Still, even though she’s spent the past few years sometimes quite literally sporting those antennae thanks to James Merry’s headpiece designs, Björk still sees her work, outlandish as it may seem to some, as firmly grounded in reality.

What could be more real, in her reasoning, than the transformative power of music, of connection, of desire? That’s the meaning, after all, of Utopia, the title of her forthcoming ninth album; a dream or an ideal that guides and shapes our behaviour in the world. And like any sensible utopian, Björk has shaped her ideals for living over years of experience and experimentation…

Kukl – The Eye (1984)

To really understand Björk’s world, you have to be aware that Debut, released in 1993, was no real debut. Ten years before it made her world-famous, 18-year-old Björk was a founder member of Reykjavík art-anarchists Kukl, and even then, she’d already been a key player in Iceland’s punk scene for several years, after releasing her true debut album, Björk, at the age of 11. The record, which came about after she covered Tina Charles’s ‘I Love To Love (But My Baby Loves To Dance)’ for a local radio documentary about her music school, was a success, but not, for Björk, an unqualified one. She’d only written one song, the instrumental ‘Jóhannes Kjarval’, and felt that the record label, Fálkinn, saw her as a novelty. Refusing the offer to make a second album with the same team, she instead bought a piano with the proceeds and fleeing into the arms of punk. Her first band was the all-female punk Spit And Snot, in which she played the drums. They were followed by an assortment of outfits encompassing jazz fusion and bar covers before she settled with playful, musically ambitious post-punkers Tappi Tíkarrass, who left behind an EP, Bitið Fast í Vitið, and an album, Miranda. Around the same time, Björk fell in with a bunch of surrealist punk poets called Medúsa. They counted among their number Sjón, who would one day become one of Iceland’s leading novelists, and would remain Björk’s lifelong friend as well as lyrical collaborator, and Þor Eldon, Björk’s first husband. It was with this group, who revelled in furious debate about the purpose of art, that Björk forged many her lasting ideas about the purpose of her music.

Tappi’s demise coincided with the birth of Kukl, a supergroup of the scene put together by radio host Ási Jónsson for the final instalment of his new music show Áfangar. Their name meant “witchcraft” or sorcery”, and the magic conjured between proved too strong to give up. Björk felt she had gone as far as she could musically with Tappi and Kukl would head down a harder path, darker, stranger, even more experimental. They band shared an interest in surrealism and how it related to Icelandic pagan literature, and in invoking the power of raw instinct – the title of their debut album come from one of Björk’s favourite book, and something of a set text among the Kukl set, Georges Bataille’s Story Of The Eye, a novella about the taboo-breaking, violent sexual adventures of two teenage lovers. In 1994, Björk said that, though the book wasn’t to be taken literally, “It says you do whatever you want, even if it’s morally incorrect. For instance, if you feel like a train is running through your head, it is. And if you feel like putting eggs inside your bottom, you should. There’s such freedom in the world that you can pick anything you want and put it in your butt… With that sort of freedom, you can play games with your mind and feel quite healthy about it." Her credo of desire as freedom to shape reality echo the words printed on The Eye’s sleeve: “Our task is reality/Our aim is reality/From reality we draw our breath/From our wishes we get our will”.

Kukl’s project was to awake and provoke, and as such their music eschewed predictable rhythms or standard rock chords, an unsettling maelstrom with lurching, shifting measures and subtly troubling tones. Tracks such as ‘Dismembered’ thrive on the interplay between Björk’s surgingly emotional voice howls and moans and co-vocalist Einar Örn Benediktsson’s purposefully unhinged stream-of-consciousness; together they summoned forces ecstatic and malevolent: the hair-raising, half-heard whispery backing vocals on the chiming ‘Assassin’ give the song an unholy, alarming feel long before Einar starts screaming. On ‘Anna’, Björk’s flute adds exotic tones while stabs of organ give a sense of dread.

While studying media at London Polytechnic, Einar had made contact with members of Flux of Pink Indians. This led to a miner’s benefit tour with Flux and Chumbawamba and a tour with Crass, and to releasing two records – The Eye and Holidays In Europe (The Naughty Naught) on Crass Records. “I was totally fascinated by Crass’s vision, but with all respect to them, they were a bit puritanical for my taste,” Björk said later. “It starts off really beautiful and positive but ends up sitting in the corner, going like, ‘I don’t want to partake of anything because it’s all polluted.’ It’s not such a healthy attitude to life.” Kukl’s mission was more about internal politics, liberation of individual desire, and throwing off old mores, as attacked on ‘The Spire’, which equates church steeple with patriarchal penis. It was a vision they pursued with single-minded focus – everything was do or die, super-highbrow intellectual, any colour as long as it was black. It’s perhaps little surprise that when Kukl fell apart, many of its former members opted for something that let in a little light and colour.

The Sugarcubes – Life’s Too Good (1988)

Einar Örn, Ási Jónsson and Þor Eldon formed the company Smekkleysa (Bad Taste) in order to put out music, literature, art and whatever else they felt fitted with their manifesto, an irreverent intellectual creed that promised to “work concertedly against anything that can be categorized as good taste or financial restraint". It was an ethos that, unlike Kukl’s, welcomed fun, colour, silliness and humour as well as surrealist absurdity into its (well hidden) serious purpose. One of the first Smekkleysa releases was an intentionally tacky watercolour postcard “commemorating” the 1986 Reykjavík summit between Reagan and Gorbachev. (You can see it on their Facebook page.) Though intended as a pisstake, it sold in huge numbers: indicative of what was to come.

Smekkleysa’s house band, The Sugarcubes, embodied the label’s spirit, replacing Kukl’s abrasive art terrorism with sly détournement. They were a “a pop band, a living cliche!” as Einar Örn put it. They dated their formation to the birth of Björk and Þor’s son Sindri, but the band would outlast the marriage, and, as it turned out, all expectations. Their first single – the undulating, bewitching ’Birthday’ – was seized on by Melody Maker’s Chris Roberts and made a single of the week, the start of a success as unexpected as that of the Reagan/Gorbachev postcard. Their debut album was colourful and bright everywhere that The Eye had been dark and forbidding: tracks like ‘Motorcrash’ embraced jangly indie pop and faux-naive lyrics. Yet there was a danger underneath the Day-Glo; on ‘Birthday’, they allowed themselves to be beautiful, but also to be play troublingly with taboos: “It’s a story about a love affair between a five-year-old girl, a secret, and a man who lives next door,” Björk revealed. “It’s like huge men, about fifty or so, affect little girls very erotically but nothing happens… nothing is done, just this very strong feeling. I picked on this subject to show that anything can affect you erotically: material, a tree, anything.” In ‘Mama’, the screams of the Kukl era are buried, only just audible, leaving a lingering sense of disease that undercuts the the lyrics’ yearning for primal comfort: “Give me a big mother, one that would always want me/ Hot embracing mother, I can crawl upon and cling to”.

In later years, some of those involved in Medúsa and then Smekkleysa would be at the core of the Best Party, the silly-serious political movement founded in the wake of Iceland’s 2008 banking crash by punk poet and comedian Jón Gnarr. Both the Sugarcubes and The Best Party ended up a success in the worlds they set out to satirise: the Best Party, running on a very Smekkleysa manifesto (‘We promise to fight all kinds of corruption – by indulging in it publicly and in full view of everyone’) took control of Reykjavík city council from 2010 to 2014, while The Sugarcubes went on to release two more albums plus a remix record and a best-of, to grace magazine covers and, most bizarre of all, to tour US stadiums with U2. “It was one big joke,” Björk said in 1995. “Yes, you can write that down : The Sugarcubes were a joke. I don’t mean we were bad or fake, but we were people who would meet each other in the pub on weekends and then suddenly decided to make some stupid pop songs.” By the time of the inaptly named Stick Around For Joy, the “joke”, for Björk, had run its course.

Debut (1993)

Björk had been honing some of the songs that would become her second Debut in her mind for years. In 1990, with the Sugarcubes on a break, she decided to start doing something about them. They first started taking shape on an unusual cycling holiday. “Lots of farmers had these little churches,” she told NME in 1993. “Just one wooden room the size of a bedroom, and they’re really over-decorated… they’ve all got harmoniums. So I used to bike between them, and have my little Walkman, and ask the farmer if I could play his organ. I’d play for two hours and then aim for the next church. I wrote a lot of tunes, and ‘Anchor Song’ is one of the ones I finished. I’d recommend it as a holiday.” She recorded two songs, ‘Anchor Song’ and ‘Aeroplane’, with a trio of brass players: a musically unconventional start, stepping outside of the template of guitar, bass and drums that the Sugarcubes and her prior bands had, however strangely, stuck to.

She’d also been exploring London’s club scene, falling for UK electronic acts such as 808 State, and sketching out some electronic music with Englishman Simon Fisher. Later that year, she arranged to meet 808 State on the set of The Word, and presented them with her demos, a meeting that resulted in collaboration on 808’s single ‘Ooops’ and album track ‘Q-Mart’ but more importantly, fuelled Björk’s dreams of electronic freedom. As the Sugarcubes began production on Stick Around For Joy, in 1991, Björk confessed her need to break free to producer Paul Fox, who, with his songwriter wife Franne Golde, helped Björk work on songs such ‘Human Behaviour’ and ‘Venus As A Boy’, and introduced her to jazz harpist Corky Hale, who plays on ‘Like Someone In Love’. Her first steps taken, Björk approached Derek Birkett, formerly of Flux Of Pink Indians, now manager of the Sugarcubes label, One Little Indian, to ask if he would help her do a solo record. “I sat with her and we put all the budgets together for it. And I based the budgets on selling 25-30,000 copies,” he told NME on the album’s 20th anniversary. “And it did 4.7million…”

Debut had found 1993’s sweet spot, a confluence of pop, dance, indie, jazz and whatever else Björk could throw in the mix. The record was produced by Nellee Hooper, a DJ from the Bristol Wild Bunch collective who’d made a name for himself with his work on Soul II Soul’s Club Classics Vol I. Introduced to Hooper by her then-boyfriend, English DJ Dom T, Björk fell head over heels into a musical whirlwind affair celebrated on ‘Big Time Sensuality’: “Something important is about to happen/And we’re both included”. The Debut team – including Pop Group/PiL drummer Bruce Smith, Shamen vocalist Jhelisa Anderson and Talvin Singh, who played tabla and other percussion, as well as travelling to India to record a bona fide Bollywood string section for ‘Venus As A Boy’ – would hit a different club every night after the sessions, and the record fizzes with the energy of discovery, Björk’s voice, so different from the usual style of dance vocalists, offering an entry point for those who wanted to join her mission of musical discovery: on ‘There’s More To Life Than This’, she runs off to the toilets of the Milk Bar nightclub to sing about nicking boats from the harbour, plotting to “rush down to the town’s best baker/To get the first bread of the morning”. The charm of the small-town girl on the rampage in the big city proved irresistible, and Debut sold 60,000 in the first month of its release, reaching No 3 in the UK chart, and earning Björk two Brit awards – Best International Female and Best International Breakthrough Act. This early success set her on a path she hadn’t expected, that of an accidental global pop star, forced to balance her art-punk origins and extreme tastes with reaching a huge new audience.

Telegram (1996)

Björk’s second mature solo album, Post, contains many of her best-known songs: ‘Army Of Me’, ‘Hyperballad’, ‘It’s Oh So Quiet’. But its dark shadow self, Telegram, found Björk trying on wildly different guises, “not trying to make it pretty or peaceable for the ear,” as she told Mixmag, but “just like a record I would buy myself”. Debut had been followed by a 1994 remix EP, the catchily titled The Best Mixes From The Album Debut For All The People Who Don’t Buy White Labels, with reworkings from Underworld, Sabres of Paradise and the Black Dog. Telegram, however, was promoted as an album in its own right, foregrounding Björk’s belief in remixing not just as a bonus to aid single sales, but as a way of reinventing her music, and of taking part in the sounds of those she admired without co-opting it. The tracklisting was wildly eclectic, from Dobie’s loping, hip hoppy take on ‘I Miss You’ or Dilinja’s skittering, nervy drum & bass rework of ‘Cover Me’ to a version of ‘Hyperballad’, the album’s lushest single, by avant garde classicists The Brodsky Quartet and ‘My Spine’, a Post offcut in collaboration with Scottish percussionist Evelyn Glennie. “I give it to the remixers and I just become a material to them. Like sugar or raisins,” she told Mixmag. “That is what’s challenging to me. To stop being the boss… Remixing allows me to always be me. It would not be honest for me to make a drum & bass record. It’s not where I come from… but I can go to a drum & bass person and say ‘Hello, my name is Björk and this is my voice and my song’ and they can make what they want from it. And you will see on the sleeve, ‘Björk remixed by Dilinja’. No one is stealing anyone else’s ideas and I don’t see it as ‘my work’ at all.”

All Björk’s singles continued to be released with a rich complement of remixes – Biophilia also has a sister remix record, Bastards. In 2005, she opened her work up to an even wider reinvention for the Army Of Me: Remixes And Covers charity album, raising money for those affected by the 2004 Asian tsunami. Putting a call out on her website, she chose from over 600 submissions from fans and musicians both amateur and professional. Biophilia went even further, allowing everyone who bought its apps to tinker with and remake the building blocks of the songs; Björk enthused about the idea of a never-finished, never-definitive album. “I think my first albums, it is straight away like this. ‘Big Time Sensuality’ or ‘Violently Happy’ I don’t think the definite best version is necessarily the one on Debut,” she told the Independent on the release of Bastards. “And even more so on Post: with songs like ‘The Modern Things’ or ‘I Miss You’, you could really imagine it going on in a club, and that’s actually how we played it live.” The Live Box set provides evidence of just how much her songs could be reworked in performance. She’s often compared her willingness to reimagine her work to jazz, where standards have no definitive version but are reinterpreted again and again – Debut had included her own take on ‘Like Someone In Love’, previously recorded by Ella Fitzgerald, Chet Baker and Sinatra, and there’s more Björk jazz to be found on Gling-Gló, the album she recorded with Icelandic jazzers tríó Guðmundar Ingólfssonar in 1990.

Homogenic (1997)

Björk’s third album, a regrouping after the dizzying rush of new experiences captured by Debut and Post, is where she really sets out her stall as a solo artist. She planned it as a record that would present her essence, and stripped it down to what she considered her core components: beats, strings and voice. In practice, though dominated by those elements – which she originally wanted mixed so that the album could be experienced in strings-and-voice home version or beats-and-voice club version – Homogenic was a sonically rich album, full of mysterious textures, bleeps and burbles. Similarly, though she’d planned to produce it on her own, stepping out from Nellee Hooper’s support (which she’d paid tribute to on Post’s ‘Cover Me’) Homogenic instead became the album where Björk refined her method of collaborating with others – Mark Bell, Markus Dravs, Howie B, Guy Sigsworth – while retaining overall creative control.

Lyrically and musically, it sets out, manifesto-style, themes that she would develop through her career: pride in her origins versus global openness to others; the unity of nature and technology and of acoustic and electronic and the breaking down artificial binaries; a belief in the power of love balanced with the beginnings of a focus on female experience – and female anger – that was the start of her rapprochement with feminism.

Production on the album began in earnest shortly after Björk was sent a letter bomb by a disturbed fan called Ricardo López, who then filmed his own suicide. Most interpreted Homogenic’s harder tones and steely-eyed covering as a response to that shock, but in fact, at least half of the album’s songs predated it, and the only song directly inspired by it, ‘Jóga’ B-side ‘So Broken’, was left off the album. In presenting a more unified, self-sufficient, tougher persona to the world, Björk redefined herself on her own terms. She was routinely patronised as a pixie, elf, mad, oddball, characterised as cute or childish. The string-stirred high-drama of ‘Jóga’ and ‘Bachelorette’ and the aggressive texture of the beats on songs such as ‘Hunter’ and ‘Pluto’ – Björk worked with Post engineer Markus Dravs to satisfy her craving for the sort of harsh, distorted sounds she loved in contemporary underground dance – demanded to be taken seriously. Björk perfected the album’s balance of beats and strings with assistance from LFO’s Mark Bell and Eumir Deodato, who’d previously helped with arrangements on Post. The extent to which Homogenic was her musical DNA, the ground from which all that followed evolved, was made clear by the 2002 Family Tree rarities box set, which divided itself into four core elements: Roots, Beats, Strings and Words. ‘To unite all these opposing systems, is to be a medium between disparate worlds trying to unite history, the present and the environment, into a song, on the radio, in a possible moment of utopia.’

Selmasongs 2000

The “characters” Björk creates to shape each song and album are typically, though exaggerated and abstracted, based on a past version or part of herself: the songs ‘Human Behaviour’, ‘Isobel’ and ‘Bachelorette’ chart the progress of one such character, Isobel, while the versions of Björk on the album sleeves are characters representing the albums as a whole. “It could be likened, perhaps,” said the artist and critic Rick Poynor in the book that accompanied the release of Vespertine, “to the difference between painting a self-portrait and using your own features as the basis of a portrait of someone else.” Taking on entirely external characters was a different matter. Björk had taken on acting roles in the 1986 Icelandic TV movie Glerbrot and in the 1990 indie film The Juniper Tree. Still, when she came to write the lyrics to ‘Play Dead’, her 1993 collaboration with David Arnold for the film Young Americans, she struggled to adopt a different mindset: “The character in the film was suffering and going through hardcore tough times and at the time I was at my happiest." The result was a very unBjörkish and extremely powerful song: angsty, negative, self-indulgent, wallowy and gorgeous.

Björk’s role in Lars Von Trier’s 2001 film Dancer In The Dark, and her soundtrack music and album Selmasongs, would prove a much greater challenge. Their battle over her character Selma was long known to have been fractious, but it takes on a far different light given Björk’s recent allegations of sexual harassment against “a Danish director”. She’d turned down a role in 1995’s Tank Girl, and wasn’t sure about accepting this role, but, she said in Inside Björk, that she was lured in by her love of musicals, one she shared with Von Trier’s lead character Selma, with whom she strongly identified. “She would defend certain things about Selma where she thought that Lars was wrong,” the film’s producer Vibeke Windeløv told biographer Mark Pytlik. “I don’t think I really acted,” Björk told Dazed in 2000. “I think I became her for two years. As far as I’m concerned, last summer I killed a man, and I was executed, and it’s a bit naive, but it is just the way I am, and Lars is the guy who got me to become a murderer.” Björk’s presentation of herself as one with Selma looks, in the light of recent revelations, like an act of furious female solidarity, protecting Von Trier’s own character from his malign influence. So, as Nicola Dibben reveals in her book on Björk, she fought with Von Trier over Selma’s last song. The last song included in the film proper, ‘I’m Scared’, is as agonising as Selma’s last hours and her punch-in-the-gut death scene. But for the credits, which Von Trier originally wanted to roll in stark silence after Selma’s death, Björk wrote ‘New World’, a beautiful sunrise of a song, picking up the themes of the rousing, Grieg-like ‘Overture’ and offering Selma a new start, an afterworld or a hope. The song closes the album as well as the film; Björk described the album’s version of the story as “my gift to Selma”. In a September 2001 US TV interview, Björk said “I’d fallen in love with the girl I was acting and I wanted to defend her”; she also expressed her opposition to Von Trier’s methods, saying “I think it’s a sign of impotency if you think you have to add cruelty to your work for it to be considered art. I think if you are confident enough in what you do, you would just let it… you would nurture it, you know? With positive energy. I’m that naive.”

The music of Selmasongs would have been fascinating enough without this backstory, a stepping stone between the grandeur of Homogenic and the interior, electronic muted sparkle of Vespertine, which she was starting work on at the same time. Björk’s albums are often something of a reaction against the album before, and as she wound down from the catharsis of Homogenic, she was turning towards quieter, subtler sounds. In 1999, she recorded a Dazed TV special for Channel 4 called Modern Minimalists With Björk in which she interviewed Estonian “holy minimalist” composer Arvo Pärt and Finnish electronic experimentalist Mika Vainio. “What seems to me has happened very much this century,” she said in it, “especially the later half, is that people have moved away from plots, structures and moved to its complete opposite which is textures. Basically a place to live in or environment or a stillness. It seems to be in this speedy times, the most bravest thing you can do is to be still.” Where Vespertine would use found sounds from around Björk’s home, and the sound of snow crunching, Selmasongs makes music out of environmental sounds of the film, Selma’s world, mimicking the way that Selma allows her musical theatre fantasies to smooth away the hardness of her life as an immigrant single mother in 60s America. The shunt and clank of factory machines becomes an exuberant dance on ‘Cvalda’; the final footfalls of the condemned and betrayed Selma on Death Row become the rhythm of ‘107 Steps’.

The emotional tone of Selmasongs is much more muted and far sadder than the furious sturm and drang of Homogenic; the beats of ‘I’ve Seen It All’ – with Björk ultrafan Thom Yorke offering a richer, softer and more dangerous vocal tone than the charmingly duff vocals of actor Peter Stormare for the album version – have something of the same character, but are fall softer, more muffled. When Selma, slowly going blind, responds to the charge that she’ll never see “your grandson’s hand as he plays with your hair” with a flat “to be honest, I really don’t care”, the clipped understatement is devastating. The wildly veering mood of the album, from the ebullient joy of ‘Cvalda’ to the horror of ‘107 Steps’, captures the duality of Selma’s world, the escapism and the fate that she couldn’t. For Von Trier, the escapism was a tragedy, a flaw that the world punished Selma for. Björk didn’t see it that way – for her, the hope that music provides is real.

Medúlla (2004)

“I keep having conversations in my head: should I keep trying to communicate with the common heart, or shouldn’t I?” Björk asked in 2007. One side of that dilemma between art music the soundtrack to Drawing Restraint 9, the 2005 Matthew Barney film that she’s also starred in; it’s a beautiful, rich record, but offers few friendly handholds for lovers of, say, ‘Venus As A Boy’. Volta is the flipside, bolting back from gallery to dancefloor to announce itself with Earth Intruders, the Timbaland-assisted tramping march of another kind of avant garde: the footsoldiers of the global poor, who Björk, infuriated by what she’d seen on a Unicef trip to Banda Aceh, Indonesia, in the aftermath of the Asian tsunami, imagined marching on the White House and stamping it to the ground.

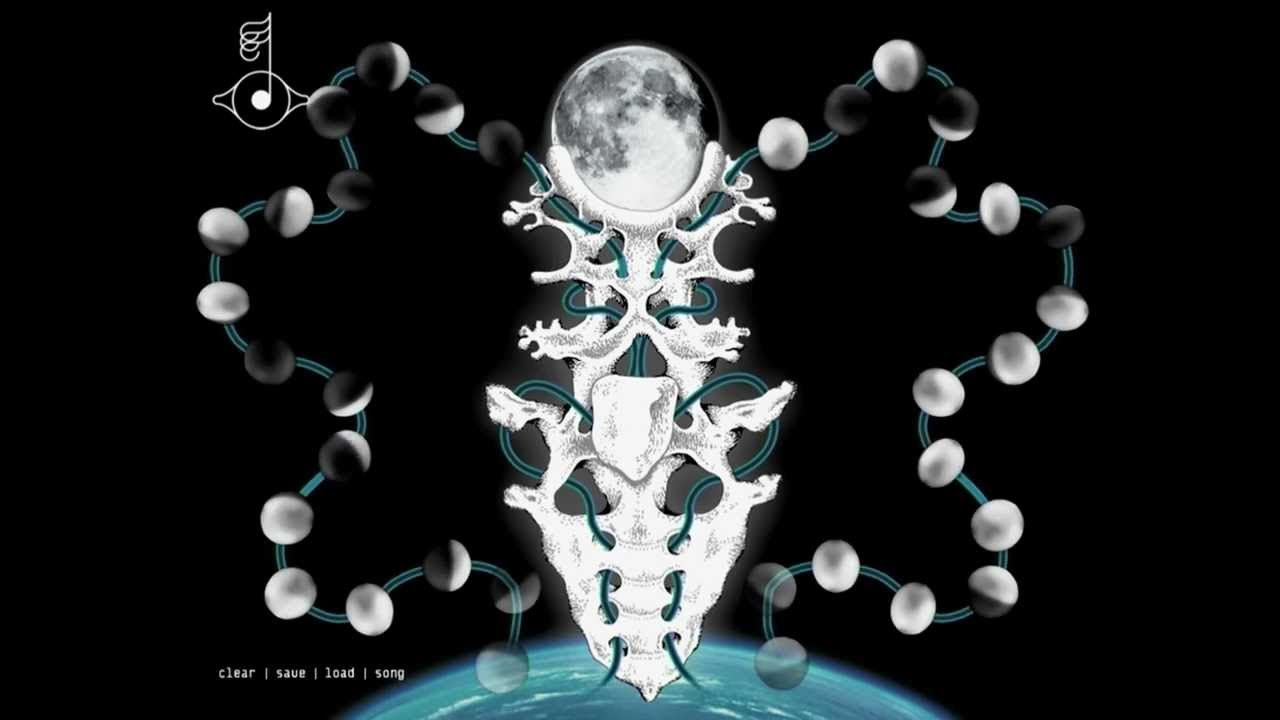

In her earliest albums, Björk had seen her role as “personal politics”. For Volta, building on the specifically female rage explored on Homogenic and the geopolitical concerns first touched on in Medúlla’s ‘Mouth’s Cradle’ (“I need a shelter to build an altar away/ From all Osamas and Bushes”) she embraced an activist stance, accompanied on stage by female ensemble Wonderbrass, blowing their trumpets and waving flags. ‘Declare Independence’, a rude, blarting techoid successor to ‘Pluto’, is rooted in Björk’s hope that Greenland and the Faroe Islands would follow Iceland’s lead in independence from Denmark, though she’s applied the song’s message to Tibet (leading to trouble in China), Scotland and Catalonia. ‘Vertebrae By Vertebrae’ was described by Björk as a new, fierce-feminist fairytale for her daughter: “The beast is back!/ On four legs/ Set her clock to the moon”.

Speaking to Attitude in May 2007, she described it as “an image of the earth mother rising up from the grave like a zombie on its back feet like "Raaaoooowwwww! l’m back!". After Isadora’s birth, she’d finally resolved her longstanding ambivalence towards explicit feminism, shocked by the princessy nature of toys on offer for children, and also increasingly irked by the tendency of journalists to credit her work “to whatever male was in 10-metre radius”.

On ‘Hope’, assisted once more by Timbaland and with Toumani Diabate on kora, she sticks her oar into the “eternal whirlwind”, reflecting on the story of a female suicide bomber who was originally suspected of making herself look pregnant, before the media discovered she had genuinely been with child. “What’s the lesser of two evils?” Björk asks, and in the face of conflicting impulses, voices and viewpoints, sticks to her earliest credo: “I don’t care/ Love is all/ I dare to drown/ To be proven wrong”.

Activism, of course, needs to be heard, not mused over. Björk brought, another voice to support hers, that of Anohni on the brooding, sultry, ‘Dull Flame Of Desire’ (a translated Russian poem by Fyodor Tyutchev, as heard on Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker) and on ‘My Juvenile’ and enlisted Timbaland to co-produce both ‘Declare Independence’ and ‘Innocence’, a tribute to the enduring power of instinct and wonder that Volta champions with brass-lit, primary-coloured gusto: “The thrill of fear/ Now greatly enjoyed with courage.”

Biophilia apps (2011)

You can trace one arc of Björk’s career right from her days in music school and her reaction against a traditional syllabus of Bach, Beethoven and dead German men. She objected at a young age to being force-fed canon – she’s always had the same attitude to the rock tradition – and craved a more child-centred, modern education that embraced Icelandic heritage. ‘I sort of strived with my headmaster,’ she said in 2001. ‘I disagreed with how his school was organized. It was not designed to make the students give and flourish and bring things out of them. Later, a younger and cooler teacher would introduce the young Björk to Messiaen and Stockhausen, but her set-tos in the headmaster’s office stayed with her. From Homogenic onwards, she re-embraced that classical training, but the longing she’d felt for a better sort of musical education, one fit for the times, stayed with her.

She’d initially thought of this as a literal school, a building – she’d hoped to take over one of those left vacant after the banking crash and turn it to good use. Then there was the idea of a 3D film, but it proved too expensive. Then, like a desirable deus ex machina, Apple’s iPad came along. For Björk, its touchscreen interface, white and smooth and tactile as the world of “All Is Full Of Love”, was the perfect tool for the immediate, visual approach to composition that she wanted. ‘Finally now, I can be like: the verse is a triangle and it goes like this, and then I twist it around, and then the chorus happens… all songs have a shape, you know,’ she enthused.

Björk called a summit of the best app designers she could find, tracked down with the help of her research assistant, artist James Merry, and they set out to build the most full-spectrum album of all time: visual, tactile, break-down and rebuildable. Each song explains an aspect of musicology linked to its own composition, links it to an element of nature and ties its lyrical and emotional themes. So ‘Thunderbolt’ explains arpeggios, their jagged leaps from note to note and back conjuring up the image of lightning, which is then picked up in the idea of inspiration a bolt from the blue explored in the lyrics: “Have I too often… craved miracles?” ‘Hollow’ is inspired by DNA, the lyrics exploring Björk’s own heredity, drawing on information from National Geographic’s Genographic Project. The accompanying app, described by biomedical animator Drew Berry as ‘a powers-of-10 exploration of the microscopic and molecular landscapes inside Björk’s body’, encourages users to tap different enzymes to build a drum machine from a DNA replicator and explore the musical building block of time signatures.

Building this sort of total, multisensory artistic whole from such leaps of connection was something Björk had craved for years. For Homogenic she’d originally planned to create a kind of virtual reality world for that album, in which each song would have its own room with imagery to match it. Like her music school’s syllabus, the technology wasn’t quite up to Björk’s vision yet.

Vulnicura (2015)

In Björk’s early records, love was not just a pursuit but a philosophy. As she made new partnerships, both creative and romantic, in the manic years of Debut and Post, she wrote songs that extolled the joy of courageous connection: love was jumping off roofs, throwing things off cliffs, unknown futures, a grand scary adventure to be enthusiastically bear-hugged. That philosophy was tested on Homogenic, where bad relationships and bad experiences forced a recalibration, but ultimately validated: ‘All Is Full Of Love’, the album’s closing track, reassures a bruised listener that though individuals may disappoint, the principle of love is immanent.

It’s on Vulnicura, though, that Björk’s philosophy of love is really put through the fire. “Family was always our sacred mutual mission/ Which you abandoned” she accuses on ‘Black Lake’, a long, painful passage from the cold floor of despair to blossoming recovery, Björk cold-comforted on her journey by heavy-hearted strings before being liberated by a volcanically explosive beat: shocked to her core, Björk returned on Vulnicura to the core elements outlined on Homogenic, this time with the assistance of her continuing collaborator Arca and The Haxan Cloak. The album moves through different stages of her grief at the breakdown of her relationship; her characters never closer to self-portrait. It’s not pure catharsis: there’s a scientific interest in the emotional ructions she’s undergoing – “I better document this” she sings on the lush, bittersweet ‘Stonemilker’, trying to negotiate separation with the best possible mindset. From a subject so profoundly painful and personal, she pulls surprising words and images, such as the “wondrous timelapse” of superimposed past embraces on ‘History of Touches’. Still, the album is emotionally gruelling, and there is a feeling of uncertain outcome, far from the strident rage and the confident assurances of Homogenic; will hope and faith in love emerge from the ‘Black Lake’? They do, just, and the record connects all the more strongly because when that faith is reaffirmed, it’s with nothing like the beneficent certainty of ‘All Is Full Of Love’. Mature hope, knocked by repeated trips to rock bottom and multiple rebirths, blows a more muted fanfare.

The development of virtual reality technology allowed Björk to create even more immersive worlds for the songs of Vulnicura than of Biophilia, encircling the viewer multiple versions of herself on the beach where the song was written for ‘Stonemilker’s 360-degree video; placing the camera on her own tongue for ‘Mouth Mantra’, becoming the Galadriel-goddess of faithless’ men’s nightmares in ‘Notget’. All was done not for technical flash but in the service of emotional connection, VR’s main purpose as far as Björk was concerned. Yet for all its healing power – “cure for wounds” is what the title means – the album is still closes before the process is finished.

The album’s credits say “‘Jóga’: I would not have survived this year without you”, and fallen back on her female friends and concerned for her daughter, Björk finds her hope more in the women in her life and in her past; on Biophilia’s ‘Heirloom’, she’d sung of “generations of mothers sailing in/ Somehow they were all ship folks” and pleaded “Like a bead in necklace/ Thread me upon this chain/ I’m part of it, the everlasting necklace”. Vulnicura ends with a song about Björk’s own mother, Hildur, begun while she lay in a coma after suffering a heart attack (she later recovered), and urging “Every time you give up/ You take away our future/ And my continuity and my daughter’s/ And her daughter’s.” As we move, this week, through ‘The Gate’, into Utopia, there’s every reason to suspect that Bjork’s future is going to be a female one.

Björk’s Utopia is out this week on One Little Indian. Emily Mackay’s 33 1/3 book on Björk’s Homogenic is out now