In 1983 William Eggleston, a pioneer of colour photography in the fine art context, went to take pictures of Graceland. Elvis’s rooms are crammed with synthetic colours and materials, but Eggleston lends his images a trademark intimacy, picturing the kitschy interiors eerily close-up and rendering them eerily quiet. Everything looks constructed, fake, but fake like how Eggleston’s photographs – quotidian images of Southern life – often look fake. It’s the fake of postwar consumer culture, especially how it manifests in a part of the United States characterised on the one hand by gaudy aesthetics and misplaced nostalgia, and on the other by racial, economic and political strife.

While Elvis and Eggleston’s aesthetic sensibilities differ, they’re both Southern artists. They were raised in northern Mississippi and came of age in Memphis; they stayed tied to the South despite finding success elsewhere; they’re known for substance abuse and evasive behaviour; on a more abstract level, their art is tied to the embedded tastes and tensions that define their home. Colour is key, in that last respect. “Elvis didn’t just buy his mother a Cadillac,” noted Mark Holburn, writing on Eggleston in Aperture in 1984, “he bought her a pink Cadillac. It is colour that describes the artifice of that persona and its attendant myth.”

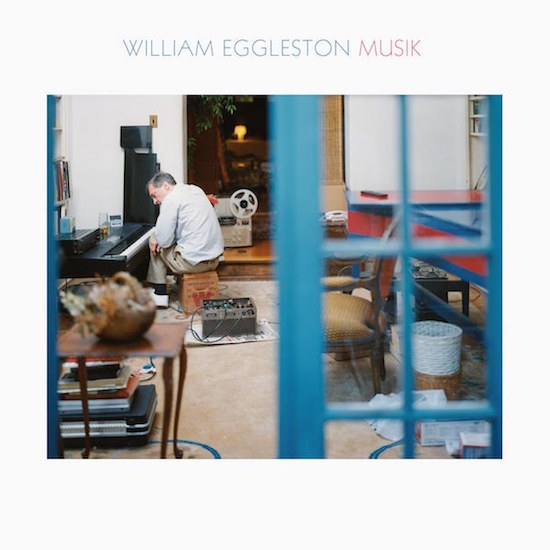

Both artists are also connected to rocknroll. By the time Eggleston visited Graceland he had ingratiated himself in the rock scene not just in Memphis but in New York City as well. In New York, in the mid-70s, he hung around Andy Warhol’s Factory and the city’s clubs as punk rock took root; in Memphis he had struck up a friendship with Alex Chilton, taking portraits of the beloved musician as well as the photo on the cover of Big Star’s Radio City. Yet while Eggleston’s passion for music isn’t a secret – a 1994 profile in Memphis magazine describes his house as “a Frankenstein’s laboratory of electronic musical equipment” and Eggleston as “almost as wrapped up in his music as he is in his photography” –

he hasn’t made the fruits of his playing public.

Enter Musik, a collection of recordings from the 80s that serves as Eggleston’s first official album. It’s neither typically Southern nor rocknroll, yet both influences percolate. Eleven of the thirteen tracks are untitled solo improvisations, distinguished by inventory numbers like ‘DCC 02.9’. Ten of them feature Eggleston on synthesizer, and one (the longest, at sixteen minutes, and perhaps the best) has him on piano. Eggleston’s photographic compositions are often described by words like ‘irreducible’, with enough material in the frame to stoke a sense of drama but not enough to lose a feeling of privacy – “a view one would have thought ineffable,” as John Szarkowski wrote in William Eggleston’s Guide (1976). While it isn’t a perfect comparison, a similar irreducibility defines Musik’s improvisations. They present a sampling of semi-abstract signifiers (snippets of recognisable melodies, synth patches that connote locations like the church or county fair) subsumed into a decidedly individual whole.

The improvisations test a variety of styles. A short introduction of bell sounds gives way to the first full piece, an exercise in baroque organ stylings that nods at Bach, one of Eggleston’s favourite composers (and the reason for his German album title). Eggleston cycles through separate fugue-like riffs, filling in transitions with electronic crescendos that lend the piece a cinematic energy. Which makes sense: Eggleston’s photos often feel cinematic, existing in time, with (clipped) narratives; his improvisations could be scores, akin to work by Wendy Carlos, maybe Angelo Badalamenti. Some pieces retain the influence of Bach or Berlioz, others retreat into new age atmospherics. Some use percussive sounds, others emulate strings and woodwinds. Yet all the tracks possess an almost saccharine romanticism, a meandering sense of movement, and an ineffable ‘colour’. It’s the stuff of popular cinema and also, in permutations, of rocknroll and of a (white) Southern taste profile – one drawn to Graceland and synthetic recreations of western art, from bronze statues to the Parthenon.

“Everyone I know who has visited the inside of Graceland… [has] returned with one word to describe what they saw: ‘tacky’,” wrote Greil Marcus in Artforum in 1984. The songs on Musik are a little tacky, too, and not just because of the outdated synth timbres. The improvisations are at once ornate and sloppy, marked by slip-ups and dead ends. The two named tracks are interpolations of kitschy musical numbers, one from Gilbert And Sullivan’s opera The Mikado and one from My Fair Lady. In Eggleston’s Graceland photos, though, Marcus identifies a “sense of dignity [that] populates the house, despite the insistent absence of the man who bought the house and lived in it.” Dignity and absence populate Musik as well: the dignity of an experimental spirit, the absence of an empty house, a culture on its way out.

Musik’s final and most moving track, ‘On the Street Where You Live’, is a hazy, half-formed take on the song from My Fair Lady (1956), which Eggleston perhaps first heard as a teenager. His version is instrumental, but the song’s lyrics speak to the private view Musik offers – its homespun baroque aspirations, nostalgia and technological tinkering. “Does enchantment pour / Out of every door? / No, it’s just on the street where you live.” Eggleston’s ‘street’, the South, as expressed through his freeform playing, is a meshwork of wonder and boredom, of grace and tackiness. He opens a door, shows it from the inside. It’s emptying out.