Angel Dust may not have sold as many copies as its predecessor in the United States, but the impression it has made on popular culture since its release has been far more profound. Though the personnel in the band was the same for both records, and producer Matt Wallace was retained to steady the ship, the followup to the phenomenally successful 1989 album The Real Thing is bolder, more bellicose and more brutal. Faith No More had built a reputation on being unpredictable contrarians, and suddenly here they were putting their money where their mouths were.

Oh to be a fly on the wall at Warners HQ when ‘Malpractice’, a Cronenbergian death metal opera about a woman who keeps returning to the operating table because she loves the feeling of a hand inside her, was first played to executives. It’s a nightmarish vision that lurches from time signature to time signature with widescreen orchestral spikes and Mike Patton screaming like an alien towards the conclusion – not the kind of thing that will get you a spot touring the world with Guns N’ Roses, as they had done to support The Real Thing.

The premise of ‘Malpractice’ is inventive, and ultimately stupid too – anybody who’s had major surgery knows you’re out for the count and are unlikely to feel anything inside you during the process, but it indicates where the 24-year-old Patton’s head was at the time. The wunderkind had been drafted in to replace Chuck Mosley in the late 80s, and all the music for The Real Thing had already been written and just needed melodies and lyrics when he came on board. As the singer of Mr Bungle, a wilfully difficult and often extravagant Zappa-esque metal band from Eureka, California, Patton found writing songs in more traditional 4/4 structures easy, and he worked quickly and effectively, much to the delight of his new bandmates. He was, however, a “fucking brat, an arrogant little baby, a child”, according to bassist Billy Gould.

"I have to say, I didn’t like Mike the first couple of years he was in the band. I thought some of the things he did were pretty immature… but he’s done really well [since],” said Gould. “He looked awful but he was the only guy we tried that really worked. But we had to take a fucking lot on. Here was this unsophisticated kid who’d never sipped alcohol before, never been in a bar, and we were all these crusty fucking guys. I felt pretty responsible for bringing this nice happy kid into this band, but he sang well. He was a lamb – he didn’t stand a chance."

The Real Thing turned Faith No More from a respected cult alternative rock band of “crusty fucking guys” from San Francisco, into an MTV-sanctioned, multi-platinum selling, stadium-filling behemoth with a charismatic lead singer who, whisper it, was a bit of a heartthrob down at the Student Union. And while the US might be the optimal market for a homegrown band and their major label, it’s worth remembering that Angel Dust outsold The Real Thing across the rest of the world. The album might have been unpalatable to many of Faith No More’s new fanbase across the pond, but Europeans in particular embraced its avant-garde metal ambitions.

What’s more, bands like Korn, Deftones, Slipknot and System Of A Down – for good or for ill – would sound very different had they never heard Faith No More’s 4th album. They are indisputably unwitting progenitors of nu-metal, but to blame them for what came after would be harsh indeed. “It is wholly wrong to blame Marx for what was done in his name as it is to blame Jesus for what was done in his,” said Tony Benn in a TV interview in 1982, and the Labour parliamentarian might well have extended it to include the Bay Area band and the crimes of Limp Bizkit had he been asked 15 years later.

Whether it outsold The Real Thing overall or not is a moot point (internet data is wholly inconsistent on this), but surely an album’s success should be judged not just on numbers, but on innovation, on lasting impact, influence, imitations etc. It’s a debate for another time, but one interesting consequence we can draw from the fact Angel Dust was the band’s most unorthodox and inventive, and – as previously mentioned – influential record, is that it’s the one that sounds the most dated 25 years on. Much of that is because it was so unexpendable at the time, and so heavily mimicked. It’s the same reason Nevermind by Nirvana, the films of Quentin Tarantino and the comedy of, say, Bill Hicks, often feel passe when at the time they felt revolutionary. It’s also the reason In Utero in reaction to the success of Nevermind sounds like a musical suicide note, and perhaps why it’s the one we keep going back to. Hindsight is a wonderful thing, and while Faith No More’s sales went on a slight downward trajectory until they split, their influence only grew, whereas Californian contemporaries the Red Hot Chili Peppers somehow managed the exact opposite, selling stratospherically while slipping ever further into irrelevancy with each release.

Following up a phenomenal success is as daunting as it is difficult, but Faith No More managed it whether by accident or design. I should probably differentiate the problematic followup from difficult second album syndrome; while the problematic followup might indeed be (what some Americans like to call) the sophomore record, it can come at any time during a career. If success has eluded an artist for a number of years, like say Pulp, then following a multi-platinum sensation must be even more disorientating than if fame and acclaim arrived early. In 1996, after almost two decades of relative obscurity, Jarvis Cocker became “arguably the fifth most famous man in Britain” according to Melody Maker. It wasn’t just being the guy who sang ‘Common People’ that saddled him with that epithet, but an infamous incident at the Brits involving Michael Jackson. This Is Hardcore was an excellent followup to the multi-platinum A Different Class, but it failed to resonate with a lot of listeners who couldn’t identify with the subject matter – namely the price of fame and the vacuity and loneliness of an itinerant life spent wanking to pornography in unfamiliar hotel rooms. Whining about fame is a guaranteed way to alienate your audience. It’s said that it’s best to write about what you know, but what happens when you can no longer write pithy observations about sex and class and celebrity as an outsider because you’re no longer an outsider?

Angel Dust avoids the trap of becoming too personal by Patton assuming an array of characters or scenarios on various songs. ‘Land Of Sunshine’ is a TV infomercial selling couch potatoes the American Dream; ‘Be Aggressive’ – courtesy of keyboardist Roddy Bottum – is a no holds barred funky hymn to gay sex; ‘RV’, which was inspired by Patton driving to the nastiest dives in town and observing the people drinking there, is an unnervingly accurate impression of a disenfranchised redneck putting the world to rights after a few drinks. Assuming characters was certainly nothing new in pop music – David Bowie had made a career out of it; though it’s interesting to note that having become incarnations of various space aliens during the 70s, his biggest worldwide success was Let’s Dance, where he wasn’t so much being himself as playing himself. He played himself – in the most modern sense of that expression – when he attempted to do more or less the same thing on follow up Tonight without the genius of Nile Rodgers at the helm. Tonight was a career worst mainly because David wasn’t trying.

As mentioned previously, Angel Dust might have been different from its predecessor, but with Matt Wallace on production duties, it wasn’t that different. At a push, songs like ‘Midlife Crisis’ and ‘A Small Victory’ were tuneful enough that they could have just about slotted into the tracklist of ‘The Real Thing’ without anyone noticing too much. The Darkness on the other hand, who’d recorded their first album on a shoestring with their mate Pedro Ferreira in a lock-up in Camden before making it big, suddenly decided – perhaps inspired during the cocaine blur they were in at the time – that they had to hire Queen producer Roy Thomas Baker. 400 reels of tape later with songs containing up to 120 guitars and 1,000 tracks per song – not to mention custom made panpipes – their followup One Way Ticket To Hell… And Back failed to live up to the hysteria caused by the first one. These schoolboy errors were nothing compared with Terence Trent D’Arby, who’s pretentious, hubristic and astonishingly out-of-touch follow up to Introducing The Hardline According To… eschewed the Motown-style pop sensibilities of the first for abstract incantations with huge overblown philosophical titles like ‘To Know Someone Deeply Is to Know Someone Softly’ and ‘I Don’t Want to Bring Your Gods Down’. Rolling Stone memorably noted that the album failed to “establish him as a visionary pop godhead. It does, however, demonstrate convincingly that he’s far more than a mere legend in his own mind.” Dodgy nomenclature was also perhaps Alanis Morrisette’s undoing – and although it would have been unfeasible to follow up the success of Jagged Little Pill (which is knocking on the door of the top ten best selling studio albums of all time), calling the next record Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie is unlikely to endear you to any new fans. The album in many ways is Alanis in excelsis, though the sheer Alanisness of its predecessor was already turned up to a point that in hindsight it’s a wonder anyone could stand it.

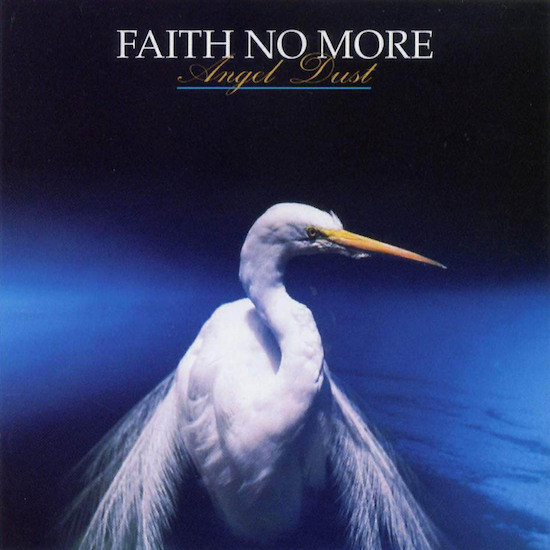

Angel Dust is named after a drug, obviously, but it’s also an oxymoron, combining spiritual beauty with death, and this deliberate paradox is borne out on the sleeve art, which features a kitsch swan on the cover and pictures of cow carcasses on the reverse. These juxtapositions give the listener a good idea of what to expect, or rather, to expect the unexpected. Intriguingly, the only drug Mike Patton was on at the time was coffee, which is immortalised in the monstrously ugly second track ‘Caffeine’. Where bands take too much cocaine, believe their own hype and decide to follow up a monster success with a double album mostly of drivel (Fleetwood Mac), overdosing on caffeine merely inspired weird sleep experiments not unlike Salvador Dali’s méthode paranoïaque-critique. Like Dali too, Patton was a self-confessed obsessive masturbator at the time. His inability to deal with screaming fans meant he rejected the sexual manna usually devoured by the rock & roll firmament.

“Goddamn, it’s not right,” he complained to Spin in 1990. “I’ve never had anyone look up to me and take what I say as gospel. Being so young, I don’t know shit; I’m in no position to talk down to someone. The kind of crowd we draw is…I don’t know if gullible is the word, but, easy. I step to one side of the stage and they go crazy. It’s so simple. It’s not as if I’m doing anything important. I mean these kids are like little lambs.”

Seen in this context, Angel Dust is a coming-of-age record where the main protagonist is corrupted by success and channels it into razor-sharp observations, cabalistic weirdness and peculiar onanistic sexual practices, a fucked up futuristic Manga Treasure Island or a Star Wars with sordid kicks and experimentalism in strange time signatures. In fact it’s an account of Patton going over to the darkside following huge success and plaudits, without the predictable assistance of too many drugs of the musician’s choice. As a spectacle it’s so much more satisfying than ‘Smiley Smile’. Angel Dust works so well because it sidesteps pitfalls and circumnavigates cliches. It is a textbook case of how to followup a phenomenon because it essentially plays by its own rules.