Ivar Wigan shoots with film. The clamshell-sallow sundowns; the gang members’ AK47s; the stripteasers – all with old-fashioned film. One reason for this is that Elephant Man ruined his digital Nikon with a jet-stream from a water pistol, at a pool-after-party in Jamaica. “I’ll have to send him the bill”, Wigan says, drily, sounding like a man reconciled to his fate of never claiming £1,000 from dancehall’s most mercurial star.

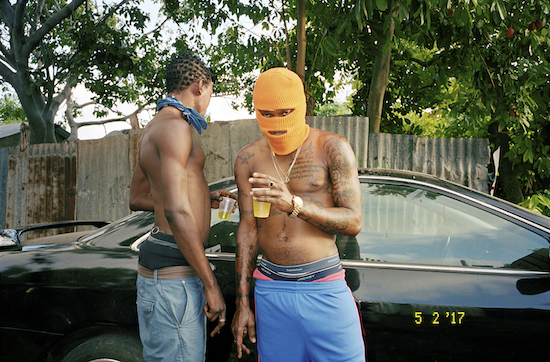

Wigan (38) has been visiting Jamaica for ten years, after a childhood in historically West Indian Ladbroke Grove. He started without a clear objective, just taking pictures along the way, making lifelong friends – giving his pictures the gravitas of trust, of shared experiences. He is not an opportunist: speaking to him you feel his sense of social injustice, his experience of the lives in his pictures, that lack opportunities, are scarred by violence. Yet he only shoots where he sees strength and beauty.

Strength and beauty. He repeats it like a mantra.

Young Love recently showed at Photo London in Somerset House, London, and will feature in a forthcoming show at PM/AM in central London.

He tells how, in January, somebody tried to kill him. “I was in my car. Someone stepped out in the road. And pulled out a Glock. And I floored the gas. And the guy unloaded it through the window … I had the window down and turned round and looked as he just unloaded through the window, and blew out the windscreen … A slug missed me by inches. I was very, very lucky. That kind of thing can happen.”

Wigan has a natty personal style – which perhaps helps win the acceptance of his flamboyant, party-people subjects, from Miami to JA. When we meet, Wigan wears chocolate velvet on his overcoat collar, a Cuban-link chain over a black jumper. He has defined cheekbones and a French nose.

Does he, notwithstanding, find it easy to fit in? “It’s a small island”, he says, as I quote a Supercat lyric “Two point five million acre / mek up Jamaica”.

“Well” says Wigan “there are around two-point-five million Jamaicans, so that’s approximately one Jamaican per acre! I’d say an aspect of it is that as an outsider you’re shown it, introduced to it, in a different way, than if a Jamaican or a Brit-Jamaican went there. He wouldn’t be received in that way.”

Ivar Wigan, Last Song

Stripping is one focus of Young Love. He visited clubs all around Jamaica (he describes one junkyard-looking venue, in the outback, which set an amazing picture in the show). There is less of the Dancehall batty-and-bubbi stereotype here – and we are shown how everyday people, and everyday bodies assert their right to work the stage. “Almost all the strippers I met were just young people out there to make some fast money” Wigan tells me. One picture shows three women: mainly thin, topless, blowing up zigzags of cigarette smoke up, fish-eyed behind the sweet-pink sunset mural. This reminds me of Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings, where Bam-Bam’s mother is a prostitute, out of pure, raw, mindless necessity. Obviously things in JA are not quite that dramatic.

Ivar Wigan, Bottom Pen

Wigan has photographed the Suri tribes of Ethiopia, done wildlife lensing in Namibia, covered the Pearl Islands, and covered the ghettos of Miami, Atlanta and LA in his 2015 series The Gods.

When he was shooting the stripbars of Atlanta, he would spend weeks in there, as a customer, before asking the no-cameras bar to take pics. Another photo, of a family mourning, we learn, are close friends of Wigan’s.

“As an outsider, some of these scenes, might be esteemed to be seen as dangerous places, what I am looking to do is to break through those barriers, and see the truth, the strength and beauty in these places, that is otherwise neglected. And people have said: ‘You’re British and you’re white, why are you taking pictures, when it’s not your topic, and not your race.’”

Ivar Wigan, View

He tells me a story of another shooting he witnessed in the US: “There was a boy who was playing music in his car … and the police stopped him. He had a gun in the car, so he tried to escape by driving down the pavement because the traffic was blocked. The police opened up, because they felt he was driving dangerously down the pavement. He opened up, so there was a gunfire both ways. A lot of people were hit in the crowd. There were eight people hit. The police killed the boy. I was standing there taking pictures at the time. I had to hit the deck.”

In histories of Jamaica, for instance in Ian Thomson’s The Dead Yard: Tales of Modern Jamaica, it is hinted that the violence and scarring from the slavery-age can explain some of the current violence. An instinct tells me the same could be said for the US. Wigan says: “Yes i think there’s a connection. There’s a huge amount of inequality in society, and the politicians are corrupt – funds are not allocated as they should be, there are few opportunities for young people, who go into gangs. I think the psychological scars of slavery might heal faster if there was less corruption, and people were looked after well.”

The tenderness Wigan finds in his visions is similar to descriptions of the Dominican Republic by Dominican-American novelist Junot Díaz. They both contains chords which are tender, tainted, raw; balanced off with a sheetrock-knife edge. One highly moving aspect is where he shows how “indie” Jamaican culture is (somewhere jock muscles and misogynist slack-chat seem the norm) – he shows girls in filigreed fishnets, covered in violet Holi-style dye, on J’ouvert, the first day of Carnival, in Kingston, St Vincent’s; guys with Scream masks on their heads while daggering.

One aforementioned picture which arouses different emotions is of an open-casket funeral, of a friend of Ivar’s. The punky, red hair of the two black women mourners makes this into strange and unusual art. Wigan tells me the murder of his friend occurred in September last year. In January, the murderer returned, and took the life of the man’s younger brother, Dada. So the mother, Barbara, had witnessed the death of two sons. In a sense, it would seem strange to want an exhibiting photographer at the funeral. But in another way, to such a senseless crime, an act of creativity, something positive, whatever it might be, must have felt good.

Ivar Wigan, Kem McLeod

We talk of Trenchtown, the Kingston ghetto, famously lensed in Perry Henzell’s Jimmy-Cliff-starring The Harder They Come. Wigan lived there for a while. “Every morning there would be a body count, and there was a war between two area dons, who are the godfather figures in the areas … So there were curfews at night – military curfews – can’t leave the house after dark. Soldiers in the street. Machine guns rattling through the night. That happens, in Kingston – and Montego Bay, as well.”

We talk about another great diptych in the series, of a gang member holding an AK47 and an Uzi. “So yeah, he wanted to show me his tools and I took a couple of pictures. I hope the photo comes across as slightly ironic, the fact that he is holding these two machine guns, that he can hardly lift! [laughs]. You can see his wrists going limp. He’s showing me tools of his trade. I’ve offset it in the diptych with a very gaudy interior of a local motel, with a print of palm trees on the wall and multicoloured wallpaper … and that was a motel that was a mile from where this guy is, who lives in a plywood boardhouse with zinc plate fences around it, who is involved in gang activities. I thought that was quite an irony, these concurrent things, the motel with these people going to the beach, and this guy who’s a mile away, with his AK47.”

So it was a funny picture? I ask.

“Well, in a way it isn’t, cos it’s real. Those are active people. I’m trying to show it in the most lighthearted way that I can, ‘cause he is not a scary person to me as I know him. But I’m not trying to take a picture of him like some kind of frightening warlord, ‘cause to me he’s just a person. But at the same time, he’s active in that world, and those things are real.”

Ivar Wigan, Baby Mama

Jamaica is a difficult country to ‘own’, as a culture, coming from the UK – its influence on us is perhaps most efficiently shown in the way its vernacular dominates MLE (Multicultural London English). But own it Ivar Wigan does, with his tender landscapes, and those guns, that seem slick with paranoid perspiration. Listening to him, it seems appropriate. “It’s not that I go out to visualise visceral things. It’s that … Jamaica is a visceral place”. The danger-intuition comes from the fact that the violence is real, the “tools”, as Wigan calls them, are sharp, and, to a viewer fired with tales of The Harder They Come’s outlaw Ivan, romantic.

“The whole tropical band of the earth” says Wigan “has an incredible light in the evening”. Wigan’s diptychs, are almost at their most potent, for me, with their cochineal-red flowers, cologne sunsets and Gauguin-verdigris clouds. We also see purple-green plantain groves, flapping in a viscous white wind, behind a blue-grey rubbish dump; and a sunset over palm leaves, behind a sunken, derelict car.

Wigan’s hero is Nan Goldin: “My cousin used to work for her. This made me think that photography could be seen in the same way as painting and fine art. It made me want to make my own art immediately.” His other heroes are Nobuyoshi Araki, Juergen Teller, Wolfgang Tillmans.

Wigan has a tattoo of a medusa on his body, created by a tattoo-artist mate who features in Young Love. Is it after Versace? I ask. He smiles and says yes. Like a medusa, or a gorgon, Wigan turns what he sees into a monument, a figure petrified in stone. Maybe he should rename his series Stone Love, after the reggae soundsystem … Whatever it’s called, Wigan’s Young Love is a quite particular portrait of a much-mythologised land, executed with a flair that befits the small island’s big aura.

Ivar Wigan’s solo exhibition will be at PM/AM from 22 June