Nicholas Currie is one of pop’s great shape-shifters. As Momus, he’s been an outsider and a crowd-pleaser, a mystery and an open book. In 1989 he breached the outer limits of the singles charts, with the wry, twinkling ‘The Hairstyle Of The Devil’. It was smart and sad and savvy – a hyper-literate fever dream compacted into four and half throwaway minutes.

Later, there would be forays into Brechtian cabaret, dark vaudeville and avant-garde electronica. He has also published six taboo-shattering novels and achieved success in Japan as a one-person Stock Aitken and Waterman-style hit factory.

Whatever his incarnation, Momus can be counted on to follow the path less travelled. It’s a journey that has taken him from the Edinburgh post-punk scene to the grey boulevards of Thatcher’s London to his present home of Osaka. Here he revisits landmark moments from a career that has straddled music, art and literature, with cameos appearances by David Bowie, Primal Scream and Japanese pop star Cornelius.

1. Being sent to a British boarding school At The Age Of Ten

"My father was teaching English with the British Council, who posted him to Athens — it was the time of the military coup in Greece. I spent a year at the British Embassy school there, and loved it: there were girls, and I could wear my hair long. But that school didn’t prepare you for British exams like O and A levels. The British Council paid private school fees in Britain, and flights to Athens every school holiday.

"So me and my brother became boarders in Scotland, and got used to flying a lot. The school was The Edinburgh Academy, set up by Sir Walter Scott. I was slightly bullied at first, but fell in with some cool boys who protected me: we bonded over our shared love for Bowie, Bolan, Lou Reed. I was eloquent, so these boys — who called me "poof" in an affectionate way, or "groovy", or "rabbit" because I had big teeth and a twitchy nose — got me to write their love letters (to girls at St George’s, the sister school) for them.

"I found my role as the school bard, or scribe, and that protected me from outright violence. Later I edited the school arts magazine and won essay, drawing and photography prizes. The boarding school was racially very mixed — I had a chaste affair with a Chinese boy, and an African was voted the best-looking boy in the boarding house — but class wise not at all: working class people from Edinburgh might as well have been another species.

"They’d be referred to as ‘thugs’ or ‘skivvies’. If ‘thugs’ trespassed on our rugby pitches, the housemaster got us to charge them en masse brandishing cricket stumps. It was very much like the awful public schools you see in Lindsay Anderson films. I hated it, and pretty much everyone who knows me will tell you it’s scarred me for life. The teachers were basically either sports-obsessed disciplinarians or borderline molesters. This set up a mistrust of authority, a desire for complete autonomy, and a need to be an exile whenever possible. The other boys were like extras from Lord Of The Flies. It’s put me off Britain, bourgeois people, males, conservatives, anybody in authority, Western culture in general."

2. Signing To 4AD Records In 1982 With My First Group, The Happy Family

"I got together with ex-members of Josef K, who were already pretty famous, and had split up prematurely. So there was already quite a bit of interest from labels. We sent out just five tapes — one to 4AD, with a letter saying we were big fans of The Birthday Party. Ivo Watts-Russell (4AD co-founder) responded, inviting us to make an EP and — if that went well — an LP later. Ivo was friendly, letting us stay in his house when we came to London, driving us around in his BMW, playing me records by John Cale, Tom Waits and Tim Buckley.

"But there was a certain reserve on both sides, too. We didn’t meet The Birthday Party. I glimpsed a blond Pete Murphy in the 4AD office once. I felt both attracted to the 4AD aestheticism and slightly repelled by it. There were Gothic elements and proto-fascist elements I disliked, along with a certain po-facedness.

"So we deliberately went against the grain and made a very ironical, verbose and bitterly comical record, a concept album about fascism and a terrorist backlash against it. We made a record called The Man On Your Street which basically tells the story of the rise of a Trump-like dictator. Actually, it was quite in tune with the dark humour of The Birthday Party’s Junkyard album, which was also bucking the 4AD preciosity at the time. And — unfortunately — The Man On Your Street is both forgotten and amazingly topical today. We’re basically living out the scenario.

"I think with all the indie labels I’ve been on, I’ve both fitted and not-fitted — which is completely natural. Ivo, Mike Alway (él Records ), Alan McGee (Creation)… they all basically formed labels around their love of a particular kind of music, a particular view of the world. They were businessmen only incidentally: mostly it was about participating in the enchanted world that they’d been formed by, the subculture of music. So we all had that in common, even if our aesthetic choices and outlooks differed wildly.

"The Happy Family ended because we didn’t get the necessary momentum to keep going. Ivo wasn’t particularly grabbed by our LP, the critics didn’t embrace us, we had no audience to speak of. I felt we were getting worse — more stiff and loud and uncreative — the more we rehearsed. The BBC came to hear us, to audition us for some TV show, and passed. I wanted to go back to university and finish my Literature degree. So I split the band up. I went back to Aberdeen, got a first, and moved to London where I reinvented myself as Momus, with Mike Alway’s help and promises that I could sign, sooner or later, to WEA. (That never happened, obviously.)

"I tend always to work to the available output slots, as it were. So Mike Alway’s promises were my context — he guaranteed that I could release records, either through Blanco e Negro (his label with Warners) or él (his own shoestring indie). Momus was one of several names I’d scribbled in my notebooks — others were Sam Hall (Evangelist), Nicky January, Chanticleer. Mike sent me to Brussels to make the first Momus EP, since he had connections with Crepuscule, Michel Duval’s label. It was appropriate, because Momus was always more in the French tradition of literary chanson. It turned out that the jazz studio I used, on Rue aux Fleurs, was where Brel recorded his first demos.

"Becoming a solo artist was very liberating. I loved working on every aspect of my records — playing every instrument, doing the production. I could never be a Morrissey, and just outsource everything except the yodelling."

3. Moving To London In 1984 And Reinventing Myself As Momus, A Solo Artist

"I don’t like my real name much. I took an avatar and stuck to it. I did it early: now there are ten new Momuses a week on Twitter. They’re mostly rightwing trolls these days, alas. I somehow wanted to be a cross between Joni Mitchell and David Sylvian, but ended up sharing tour vans with Primal Scream. London was a cornucopia. Everything was free. The council paid my rent in Chelsea because I was signing on. I dated a journalist who got me into gigs and parties and gave me keyboards Casio had sent to Smash Hits for review. I got free haircuts at the Vidal Sassoon Styling Academy (you had to let them experiment on you, but that was okay). You could even get into art movies free if you claimed to work at another indie cinema. If you dated your plugger or just visited lots of labels you got free promo records. And when you got slightly famous the sex came free too.

"I toured Germany with Primal Scream. I remember bonding quite well with Bobby — who was listening to lots of Prince and T. Rex — and finding the others very amusing. There was one night in a pizzeria in some godforsaken army town — Mönchengladbach, it might have been — where they had me in stitches with their anecdotes about growing up in East Kilbride. I duetted with them onstage on Stooges numbers. They had some immature satanist-sadist hangers-on, though, who annoyed me. I hate all that Crowleyite, Gilles de Rais nonsense."

4. Moving To Paris In 1994 With My Bangladeshi Bride, And Writing A Hit Song For Japanese Singer Kahimi Karie On My Honeymoon

"In 1993 the borders came down: the freedom of movement thing we’re now losing, if we’re British. I felt much more at home in Paris than I did in London: my basic culture was more French, partly because my mother is a huge francophile and spent time in Paris in the 50s, nannying. Also, I married Shazna in 1994 and we needed to put some distance between her and her London family, who were not amused that I’d rescued her from Bangladesh.

"I was being championed by Karie’s boyfriend, Cornelius, on Japanese radio. She was a photographer who embarked on a music career. Cornelius and Kenji Takimi, who ran Cru-el Records (obviously indebted to él Records), drafted me in to write for Kahimi. I’d already produced another Japanese singer at that point, The Poison Girlfriend. It was intoxicating to see that the records I’d put out on él and Creation were having an impact somewhere. I didn’t think that Kahimi would get as big as she did; I saw it more as vindication, really, of a worldview I’d been part of: an anglospheric Gainsbourgianism, if you like.

"I spent the 90s rolling in publishing money. When I moved back to London in 1997 I was able to rent a pretty nice penthouse flat near the Barbican. I didn’t have to do any work I didn’t want to. And the records I made for Kahimi could be as obscure and literary as I liked. That’s the upside of the status English (or French, or Italian) has in Japan — it confers an aura, an atmosphere they like. It’s like using a certain typeface. As long as you stick to the typeface, you can make the letters spell anything. Refined Japanese women in their early 40s remember me from their schooldays."

5. Inventing Analogue Baroque In 1998, A Songwriting Style Which I Think Of As A Major Step Beyond Pastiche Into Originality

"I think I’ve always been very determined to avoid vague, abstract songs and focus instead on quite concise, provocative stories. I’m drawn to very brief, pungent tales with some degree of moral provocation going on, and often an unreliable narrator. The sound of a slightly libertine humanism, with a production that avoids reverb, big drums, guitar heroics. I wanted to make songs like early Ian McEwan stories, or Brecht ballads, or Browning poems, or Aesop’s fables, or the dreamy sex poems of Pierre Louÿs crossed with the harder transgressions of Georges Bataille.

"I think Analogue Baroque started with me reading Martial and listening to Schubert. The style features through-composition, minimal repetition, harpsichords, concision and offhand, clear and conversational lyrics. I got this sudden insight that computers and synths could be baroque and retro and mannered. It coincided with a big push in America, so this was essentially me incarnating, for Americans, a certain idea of what it meant to be European: it meant being mannered and foppish, witty and bitchy, libertine, sophisticated. To some extent this worked — in New York and San Francisco, notably. But it got me some terrible reviews, too. Robert Christgau said: ‘In one of his many clever songs, Nick Currie compares his quest for fame to God’s and wonders why the big fella gets all the coverage. The answer is that God is a nicer guy.’"

6. Having My First Solo Art Show In 2000 At Zach Feuer’s Gallery In New York

"I don’t really consider myself to be creating visual art. I got to play in the New York art world for ten years or so, largely thanks to a gallerist called Zach Feuer. I had no visual practice, nothing to sell. I just told stories in a gallery context. Telling stories is what I’ve done in every context. If you do it in a gallery it’s called art.

"Songwriting is more traditional, more formatted. This is where the art world wins: whereas songs have an inherent lumber of conservatism — the heart is Tory, essentially — the art world is the designated space of originality in our culture. And that allows you to be as eccentric, as pretentious, as affected, as ridiculous as you like. There isn’t nearly enough ridiculousness in pop music, and when there is, it’s too campy and shallow. What we need is deep ridiculousness, serious ridiculousness.

"Zach Feuer initially just wanted me to perform at an opening. And then a free month in his gallery opened up, and he impulsively proposed that I do an art show of some kind. I came up with the idea of doing a sort of Alan Lomax faux-folk collecting thing in the gallery. So I recorded visitors singing songs, and made up myths and legends about people. It was all about the collision of fakeness — which I see as a fertile thing, a laboratory — and authenticity, which seems to promise humanist values like moral goodness and trustworthiness. It was a show about America, or my perception of America. Some of the themes reoccur in my UnAmerica novel. It was the first of three shows with Feuer, and led to my inclusion in the 2006 Whitney Biennial as "the unreliable tour guide".

7. Starting Again In Berlin In 2003

"I still think of Berlin as my "spiritual homeland." I’d spent the last few years shuttling between Tokyo and New York, having a really playful and fun time in the art world. Life was as good as it gets — although I was possibly turning into an unbearable ponce, a spoilt playboy. 9/11 basically changed everything. I witnessed it from the roof of my Orchard Street apartment. The era of irrational exuberance ended. Our current era — war-torn, terrorism-tinted, anxious, paranoid, anti-pluralist — began. Berlin still had an atmosphere of experiment, tolerance, progressiveness and play. I’d burned through my money and was poor again. But Berlin allowed me to live well, amongst people who thought like me. I was already 43, but I felt incredibly young. I could dress in a new way, find new lovers, fill up a new apartment with clutter from markets.

"Berlin is one of the most liberal places you’ll find anywhere. It’s also got that wonderful German seriousness about culture. People aren’t chasing money the way they do in London or New York. They really want to live well, and think and feel deeply. One tiny example — I saw a poster yesterday for a film about Joseph Beuys. It’s on at two or three cinemas across Berlin. Beuys meant a lot to me when I was 20 — I attended his Free International University when it came to Edinburgh. The fact that that film can be on in several cinemas says something. Beuys’s continued presence says something. In London and New York it would be Warhol — and Warhol connotes something different, something that’s not sufficiently separable from hype and marketing and PR and plutocracy for my liking.

"’Aghast’ doesn’t even begin to cover my reaction to Brexit. It’s a tragedy. Home Counties conservatism has finally sunk the whole ship. It was always a fatal character flaw, but now it’s actually letting in water. I thought at least neoliberal semi-rationality would countervail, with its own demographic and economic need for multiculturalism.

"But no: the old — and the non-urban — are screwing everything up for the young. They did it with property speculation, now they’re doing it with citizenship and basic human rights. My one hope is that Scotland will secede, and the English will eventually be ring-fenced in a sort of toxic province. But that’s to discount the rise of authoritarian populism in other places across Europe. The big picture — almost by definition — is still a global one, though. We still face global problems that require global solutions — public solutions, not private ones."

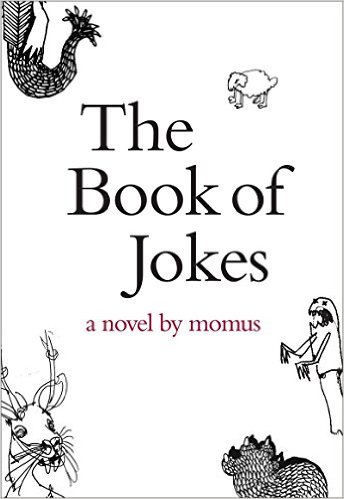

8. Publishing My First Novel, The Book Of Jokes In 2009. There Have Been Five More Published Since Then

"Reading a book, you have to be in a fairly bland environment — well-lit, ventilated, warm, relatively safe, without too many interruptions. But obviously you want to be reading about something a bit more exciting than that, something dangerous and thought-provoking.

"Lies, jokes, murders, sex, other worlds, the unlikely, the unforgettable — these are all things it’s interesting to read about, to be transported by. In art you can imagine whatever you like, and books are the cheapest, most direct way of doing that. Having said that, I quite like quiet books as well as riotous, rabelaisian ones. It’s just that, when I write, I like to keep myself amused by going to cultural faultlines, places of unsafety.

"You learn so much more in those earthquake zones. Smashing things down is a way to learn about them. Selfishness is a way to understand consideration. For instance, in The Book Of Jokes there’s a scene where the Father character is waving his enormous penis around in front of a peasant woman on a bus, and the narrator sighs: ‘Our freedoms must end where those of others begin. It’s a truth my father never seems to have learned.’

"I’m quite a serious and apprehensive person, not really the life and soul of any party. But I am drawn to intelligent, dark humour. It marks a site of despair, and turns it magically into a site of pleasure. I lost, then I laughed about it. The danger is that that can easily turn into a celebration of the very things one ought to be fighting against.

"So, while there’s a liberal and liberating potential in satire, for instance, there’s also a danger of collusion and complacency. You end up fixating on the things you’re supposedly attacking, enlarging and legitimating them. You dilute legitimate spleen."

9. Moving To Osaka In 2010

"It’s a city I used to visit reluctantly, preferring Tokyo. But now I appreciate its working class energy, and a certain live-and-let-live quality. Compared to Tokyo, Osaka is cheaper, more working class, more extrovert, more eccentric, more ‘Latin’, more humorous, less authoritarian, less tidy, more Korean. Tokyo is a big office; Osaka is more about food and sex. It’s a great cycling city, enormous and flat, with endless grids of almost trafficless backstreets.

"I love it when it’s hot, really hot, and the girls are almost naked, and the cicadas are deafening, and suddenly there’s a wild shrine festival and people in loincloths are running down the street shouting ‘Sora! Sora!’ I think Shinto is incredibly central to Japanese life, and it’s very little understood in the West, where people fixate on Zen. Shinto is all about sex and fertility and food and the seasons — the febrile power of nature. I’d have to get all Henry Miller to explain it, but it’s a key reason I love being in Japan. I see it everywhere, that pagan love of the life force. Something, unfortunately, that Christianity squatted over, shat on, and throttled in the West. My records sound pretty much Japanese now, don’t they? I mean, more Japanese than a Japanese artist’s records would! They’re all shamisens and claves."

10. Being Noticed By My Hero David Bowie In 2013, When I Covered His Song ‘Where Are We Now?’

"He was my saviour at boarding school, the one glimmer of light I could see in a glowering grey sky. He signalled that you could be an artist, a multimedia artist using the electronic media, and triumph over dullness and conservatism. I love pretty much everything he did in the 70s. I also like his weird 60s cabaret period — those little story songs about bombardiers and monks. I hate what he became in the 80s. I wish he’d been more experimental. He was just beginning to get that back when death snatched him from us. It’s been a horrible bereavement, but — as I like to say — we now have to be the Bowie that we wish to see in the world.

"I was on a ferry between Busan and Fukuoka when I heard he had passed away. Somebody Facebook-messaged me. The sea and the sky had a nacreous glare, there was something stifling in the air. When I got to Fukuoka it was Coming Of Age Day, when all the 20 year-old girls dress in kimonos with fur collars. They looked gorgeous and young and flamboyant, almost how Ziggy looked in his Kansai Yamamoto gear. It was the life force, the thing that Bowie valued above all.

"I got on the Shinkansen and wrote a big piece about what Bowie had meant to me, and how bereaved I felt. I’d already been doing the Bowie concerts while he was still alive. He’d been aware of them. I’d been described by The Guardian as “the David Bowie of the art-pop underground”, and he’d retired from performance, so I thought I’d do a cabaret that emphasised his avant-garde side, rather than the glitzy hit packages you tend to see.

"I think he appreciated that, and that’s why he instructed his website to promote the shows, and called my cover of ‘Where Are We Now?’ "so cool". That meant the world to me: that the person who’d incarnated cool all my life had used the word about something I’d done.’

Momus will be at Where Are We Now? June 2 – 4, as part of Hull UK City Of Culture 2017