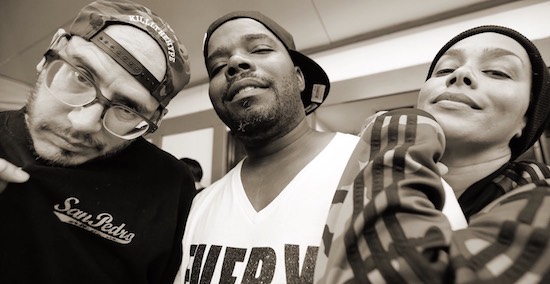

RP Boo and the late DJ Rashad are widely regarded as the pioneers of footwork. They have toured around the world several times over, – DJ Rashad played in Europe as early as 2008 – and both have released critically acclaimed albums on UK labels.

Yet there is a third pioneer who has received much less attention, and only this year embarked on his first tour outside the US.

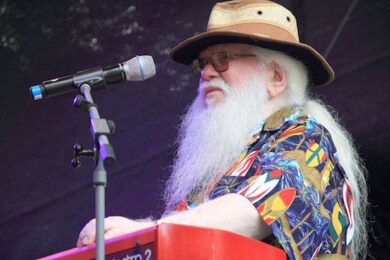

DJ Clent is one of the three founding fathers of footwork, a Chicago-rooted electronic dance music genre known for its use of feverish syncopated rhythms, half time and extensive sampling – marrying it as close to hip hop as the ghetto house genre it spawned out of. Born to DJ parents in the South Side Projects, Chicago, he was playing with his mum’s records from the age of two.

After releasing his first EP at the age of 16, he debuted on Dance Mania two years later in 1998 and created the first footwork collective – Beatdown House – in the same year with DJ Rashad, RP Boo and Majik Myke. He has gone on to release dozens of records on labels such as Juke Trax (which gave a home to juke and footwork after the fall of Dance Mania) and Planet Mu. In 2013, he established his Beatdown House collective as a label and two years later released his enthralling debut LP on Duck N’ Cover. He embarked on his first tour of Europe in Spring 2017, more than 20 years after he released the first ever footwork record.

The first allusion to footwork in Chicago was on Wax Master’s 1995 ghetto house track ‘Foot Work’. Although many believe the genre descended from juke – a sound coined by DJ Puncho and Gant-Man in 1998 – the originators all spell out that footwork and juke both rose out of ghetto house.

Juke – which was little more than another name for ghetto house – grew rapidly into use but faded within a decade. In the shadows of juke, footwork slowly and continuously evolved, before being thrown onto the world stage by Planet Mu’s Bangs & Works series in 2011 and later taken to another level of notoriety by DJ Rashad’s Double Cup on fellow UK label Hyperdub.

DJ Rashad, RP Boo and DJ Clent, who were all initially dancers and DJs for ghetto house dance groups, were the first to implement the initial branches that grew into a distinct sound. Inspired by dancers who wanted to challenge themselves with faster and more intricate moves, DJ Clent’s 1998 release 100% Ghetto – We 2 Ghetto 4 Ya broke away from the bouncy 4/4 sound, introducing syncopated halftime rhythms and repetitive refrains. The superior track is the transfixing trumpet-led anthem ‘3rd World’, which is widely regarded as one of the first footwork tracks, alongside RP Boo’s ‘Baby Come On’ – which was made in 1997 but not officially released until 2015 – and DJ Rashad’s ‘‘Child Abuse’ (1998).

DJ Clent says that footwork has no single beginning, developing on a continuum out of the roots of ghetto house, but that he, DJ Rashad and RP Boo started it. He argues that many tracks from the period were lost or never officially released but does take credit for releasing the first ever footwork record – a year before any of the aforementioned tracks existed.

Released on DJ Slugo’s Subterranean Playhouse in 1996, DJ Clent’s Hail Mary EP has characteristic rhythms and repetitions that isolate it from the ghetto house tracks of the time. The eponymous track, at 77bpm halftime, is the closest of its time to the 160/80bpm speed that footwork evolved into. Unlike ‘3rd World’, which sped up the sound to challenge the dancers, Hail Mary slowed things down, giving the dancers space to work within.

Hail Mary is not the most celebrated or accomplished early footwork release, with DJ Clent taking his sound to another level on ‘3rd World’, but it was a vital precursor to one of the most exciting music genres of the last decade. The release of Hail Mary, footwork’s first official record, marks DJ Clent as a true pioneer of the genre.

Your parents were both DJs right?

DJ Clent: Yeah. My mother and father met at a DJ pool. I grew up around music all my life: funk, jazz, soul, disco and R&B. She stopped DJing in the mid-80s but had 5000 records. That’s where a lot of the samples in my music come from.

So you had all those records to sample?

DC: No. My house burned down and we lost everything. But my memory of growing up in a house full of music – Funkadelic; Earth, Wind and Fire; LTD; Jeffrey Osborne – has inspired so many of my tracks. Every Sunday, even today, we wash clothes in the house and listen to music.

How was life growing up in Chicago?

DC: It was fun. I used to walk from neighbourhood to neighbourhood. I never really had a problem. It wasn’t as bad as it is now. I would hate to grow up in Chicago now.

In a previous interview you mentioned being involved with Gangster Disciples. Were you ever part of the infamous Chicago gang?

DC: You’re pretty much whatever your neighbourhood is. A lot of my family is part of that life. I did just enough to be affiliated and stay safe at the same time. The DJ is always safe in the neighbourhood because people always want them to play the music.

Did you get in any scary situations?

DC: I’ve been in a lot of scary situations. I used to buy blank tapes at a drug store called Walgreens, so I could make mixtapes to sell at the skating rink Route 66. My friend and I were walking back home through someone else’s projects and some guys pulled a 12-gauge shotgun on us, thinking we were the rival gang. Luckily, I had just DJ’d for them a couple of nights before and they were like, "That’s DJ Clent – he’s cool – let them go." I’ve been shot at, robbed, had guns drawn on me. It wasn’t really that bad to me. It could have been worse. I could’ve been shot. I’ve been in a lot of crazy situations just as a DJ. From people stealing our tracks to recording us DJing at a party and selling a mixtape with our tracks on it – without us knowing. I believe it makes you a stronger person.

Why do you think it’s so much worse to grow up in Chicago now?

DC: They tore down the projects and locked up all the gang chiefs: people who could control situations. Now, there’s no authority in the neighbourhoods. It’s neighbourhood versus neighbourhood, crew versus crew, and in each crew there could be five different gangs. Back in my day you couldn’t just kick off a war without proper reasoning. Now the youth have no one to answer to. They do what they want and I stay out of their way. You come into this world lost. Without people running the neighbourhood, you get even more lost. It’s stupid now.

Have you ever thought about moving to a different neighbourhood?

DC: Definitely. I live in the suburbs now.

Would you say you are still in and out of that lifestyle?

DC: I still hustle. I’m not going to lie to you. Music doesn’t pay all the bills. I’m one foot in, one foot out. I just make sure my foot is not all the way in. It might be a big toe – just enough to get me by. It’s hard, but after this trip, I believe I’m not going to have to hustle anymore. That’s the ultimate goal.

Why do you think it has taken so long for this tour to happen?

DC: I have a couple of ideas but it’s not worth speaking about. One thing I can tell you is it’s never too late. Everybody has his or her time. Maybe this is my time. I look at it like this: when God thinks you’re ready for something, he’ll make sure it happens. Just because you think you deserve it doesn’t mean you’re ready for it. Missing out on touring made me a better man for my children, mother and fiancé. I would have missed out on a lot of important times in my children’s life. My mum really needed me. I feel like it just wasn’t my time. I had way more important things I needed to do other than music.

What was your setup when you first started producing?

DC: I didn’t have my own equipment. My first tracks were made at DJ Greedy’s house. He had a Roland R70 and a cheap DJ mixer with a push button sampler. We would make the beat in the R-70 and then record samples into the mixer. There was no midi, no sync. Now, everything is automated. It’s much easier.

When did you get your own equipment?

DC: I was 16 years old. I made a mixtape called 100% Ghetto Part I, at DJ Greedy’s house. We sold 5,000-10,000 of those tapes and he took the money and bought me a brand new MPC 2000 and my first computer – in 1997.

What were the reactions to your music at first?

DC: In the early days, I used to take my tracks to a dance troupe called Phase 2. They would say, "You should do this. You should do that. That one’s cold. Rock that one at the party tonight". I would take that input and make more.

You were a dancer yourself, right? When did you start dancing?

DC: I was dancing at about 11 or 12, in a group called Lake Park Dancers. Then I started DJing for a group called You Go Girl Posse. From that, I met Phase 2, K-Phi-9, U-Phi-U and House Arrest 2, and started DJing for House-O-Matics.

Are you still dancing?

DC: No, no, no, no, no. I got old. I’m 37 and I’m out of shape so I don’t dance anymore. I might kick a leg every six months.

Were you good?

DC: I was OK. I’m not going to lie and say I was burning everyone. I got out of it and focused more on DJing.

When did the tracks start getting sped up?

DC: The producer side of it is my fault. The DJ side was Traxman. He would play a Dance Mania record on 45rpm. It was fast and the dancers loved it. My idea was – instead of making the tracks slow and playing them fast, with our voices sounding like chipmunks and the bass pitched high – why not make the tracks fast? That’s when it changed. It was the end of 1997.

What did your mentor, DJ Greedy, think about how the sound sped up and changed?

DC: He’s proud of me. He’s pure ghetto house but he understands why we did what we did. We didn’t want to be a DJ Deeon or DJ Slugo copycat so we came up with our own sound – which happened to be footwork.

What was the first 160bpm track?

DC: I’m going to have to ask Jammin Gerald, but ‘Space Chair’ was fast. Beatdown Compilation, with me, DJ Rashad, Majik Myke, DJ Silk and RP Boo, was the fastest record on Dance Mania. It only came out on test press.

You could argue that ‘3rd World’, which came out two years before ‘Beatdown Compilation’ was already footwork. Was ‘3rd World’ the first footwork track?

DC: That was when it changed. Me, RP Boo and DJ Rashad started it but there is no first footwork track. There are several starts and there are many tracks that were made before ‘3rd World’ or ‘Baby Come On’.

Would ‘Space Chair’ be the first?

DC: That was more of a fast ghetto house track. I really can’t pinpoint the first track. We’re so detached from back then – 1996-1997 – a lot of the tracks were lost or stolen. The people called ‘3rd World’ the first but I think Hail Mary would be.

Why do you think people see ‘3rd World’ and not Hail Mary as the first footwork release?

DC: I think ‘3rd World’ just overshadowed it.

What was the process for creating Hail Mary?

DC: It was pretty much the same process as ‘3rd World’. I used a Boss 660 drum machine and Roland JS30. It was made at DJ Greedy’s and my own studio.

What was the reaction to it?

DC: I first played it at Route 66 and it got a great response from the crowd.

Around the same time, DJ Puncho and Gant-Man developed a new sound – juke. What was your involvement?

DC: That was their thing. We would purposely make tracks without saying "juke". I started calling my music "project house". Sadly that name didn’t take off. When you play ghetto house in a club in Chicago they call it juke now. It swallowed everything, even footwork. Everything ghetto in Chicago is called juke now.

You set up your own label Beatdown House, in 1998. How did that happen?

DC: We were just a crew of likeminded people that made tracks – Me, DJ Spinn, DJ Rashad, RP Boo, Majik Myke, DJ C-Bit – even Million Dollar Mano. It wasn’t a label or an organisation. It was just something we all claimed.

How did you all meet?

DC: We met at a party: me, DJ Rashad, DJ Spinn and RP Boo. I was selling mixtapes and DJing at Route 66 at the time. They didn’t believe I was DJ Clent. They said, "Man, I thought you was grown, we’re all the same age." I said, "Yeah, I’m a kid just like you". I had a huge blessing: DJ Greedy. Whenever he sold a tape, I sold one. I was like his little brother. Those tapes spread to the south suburbs and that’s how DJ Rashad and DJ Spinn heard them. DJ Rashad used to catch a bus all the way from the suburbs to The Lowend to make tracks at my house. I taught him how to use the MPC.

Did you and DJ Rashad make tracks together?

DC: We made a few together but the mass majority – the thousands – he made on his own.

Yourself, DJ Rashad and RP Boo all have your own style within footwork. What makes a DJ Clent track unique?

DC: My tracks are simple and straight to the point. I put an energy or feeling into the track that can translate to the person listening. On the Hyper Feet record, there is a track called ‘Don’t Leave Me (Baby)’. I made that track because I was having some problems with my fiancé at the time and I wanted to say that to her. The samples were talking to her.

Last Bus To Lake Park – your debut album – came out in 2015. For me, that is one of the best full-length footwork records. What was the thought behind it?

DC: I just really wanted to showcase DJ Clent in every capacity from juke to ghetto house to footwork. It may be 160 but there are different nuances and each track doesn’t feel the same.

What is next for DJ Clent and Beatdown House?

DC: We have new releases from DJ C-Bit, DJ T-Rell and DJ Roc, and our first releases from Lil Mz. 313 and DJ Larry Hott. We plan to come with a lot this year. My new album is called Everybody Hates Clent. I’ve been playing a lot of the tracks on tour.

When were the tracks for ‘Everybody Hates Clent’ made?

DC: They’re all new songs pretty much. I remade one of DJ Rashad’s tracks – ‘Last Winter’ – because I haven’t dedicated a track to him yet. It’s me saying, "Where were you when I needed you last winter" because he was my boy. I’m finally going to let that out.

How did DJ Rashad’s passing away affect you personally?

DC: When DJ Rashad passed, we were in an argument. I never got the chance to square it off with him. It bothers me almost every day. Every time I listen to footwork it bothers me.

Was it the Machinedrum situation?

DC: Yeah, it was the Machinedrum situation.

Did you resolve your differences with Machinedrum?

DC: Machinedrum and I don’t have a problem. We’ve played in Detroit and New York together a few times. It’s not a problem. It wasn’t right but we got to the business of it and moved on.

Your son is making footwork right? Is there a next generation coming through in Chicago? After the likes of DJ Taye, DJ Earl and Sirr Tmo, there seems to be a gap.

DC: He is the next generation. You’ve got other people coming through but for the most part – the younger generation – would be my son, Corey. We have an EP called Me And My Son which we’re two tracks away from finishing. As long as he keeps doing well in school, we can go in the studio. We’re going to finish it this year. All of the proceeds will go straight to his college fund. I don’t want a penny off of it.

What’s next?

DC: For BEATDOWNHOUSE we started our own online radio station; also there’s the Beatdown radio app for iOS and Android that plays juke, footwork and ghetto house 24 hours a day/7 days a week.