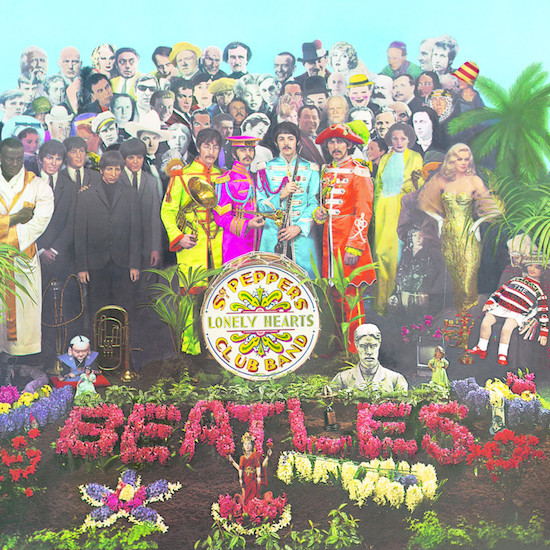

I’d heard that Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was the best album of all time, so when I happened upon a picture disc, displayed behind the counter at Birmingham record shop – a snip at £2.99! – it was a no-brainer. This was 1983. I was 13. My pocket money was £5 a week. Every penny went on records, so the fact that I still had £2.01 change from the best album of all time felt like an absolute triumph. Plus! Picture disc! It would take years for me to realise that the version of Sgt Pepper I bought that day is almost certainly the most substandard one in existence. Showing a picture disc to a committed audiophile is an act comparable to showing a shower head to a cat or a picture of Les Dennis a picture of Amanda Holden. Even worse, the version of Sgt Pepper available to record buyers in the early 80s was the stereo one, famously mixed in less than an hour without the band even present. It was the mono one that the band wanted to get right: the one which matched the hardware that most people would use to listen to it.

But I didn’t know any of that in 1983. Because Sgt Pepper was the best album of all time, I knew I needed to listen reverently, so I waited until the house was empty and then, in the lull between Bruce Forsyth’s Play Your Cards Right and Juliet Bravo, I took the record out of its bag, placed it on the stereo in the posh room that no-one ever used, plugged in my headphones and really concentrated. I didn’t give myself the option of not liking it because cleverer people than me had already decided that it was the best album of all time, but I was expecting this record to transform me, to push me a significant distance in the direction of adulthood.

I expected weighty themes dealt with in allusive terms. The Dionysian pretensions of The Doors were more comprehensible to me. I thought that was what wisdom sounded like. And although ‘She’s Leaving Home’ and ‘Getting Better’ were pretty, I struggled to square the record that critics described with the record I was listening to. All of that happened later, in tiny increments. Driving into a blizzard on the west coast of Scotland on the day the news broke about Richey from the Manics disappearing, ‘A Day In The Life’ came on the radio – that was a moment. By the time I was 16, I had sort of realised the hole that Paul was fixing couldn’t really be mended with a hammer and nails. I had quite a lot of those sorts of holes too. ‘Being For The Benefit Of Mr Kite’ scared the shit out of me then and is still apt to do so now. The Chemical Brothers’ live deployment of ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise)’ somehow also brought me to a deeper understanding of the album’s intentions.

Sgt. Pepper was an album for all of life: not just the lysergic all-nighters, but the bright blue mornings which followed them. Not just for the 13-year-old for whom the tunes are enough to be getting on with, but it’s record that releases its secrets to you as you go through life. It’s a trick that Paul finessed on ‘Penny Lane’, a song which pauses the videotape of memory on a scene to which its creator can never return, and as a result, gets sadder with every passing year. Of course, ‘Penny Lane’ – though recorded for Sgt Pepper – didn’t make it onto to the album, but ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ did. I never expected that one to leave me emotionally blindsided, but of course, that’s the genius of young Paul again: "Indicate precisely what you mean to say/ Yours sincerely, wasting away."

And because (unlike those Doors records, which started to sound a bit silly by the time I reached 18) Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is an album for all of life, I can’t imagine a time when someone holds it up to a new light or reveals it in some altered form that I won’t find absolutely fascinating. All of which helps explains why I’m one of a hundred-odd people sitting in Studio 2 at Abbey Road, the room where The Beatles recorded Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, whose 50th birthday is set to be marked by what must surely be the most thorough reissue it will ever receive. From May 26th, Beatles’ fans will have to ponder whether they’ll shell out something in the region of £110 for the six-disc Super Deluxe Edition or content themselves for the two-CD, double LP or stand-alone versions. For some people, it’ll be one reissue too many. After the 2009 mono remasters and the 2013 vinyl remasters, I get that.

Strip away all the extras on this one though, and the main event is the 5.1 Stereo Surround Sound version that Giles Martin and Sam Okell have been working on. As Martin explains, this is a remix as opposed to a remaster, which means that he worked from the individual four track tapes in order to build a stereo version that could finally supersede the one that was put together as an afterthought back in 1967.

The gimmicky uncoolness of stereo has been a constant among serious music fans for pretty much as long as I can remember. But when you’re on a budget, beggars can’t be choosers – and so the first version of Rubber Soul (yes, Rubber Soul, I’ll come back to Sgt Pepper in a minute) I ever owned was a stereo one. This was the "full dimensional stereo" of the American pressing, with its inferior track listing. I returned home from a trip to Seattle in 1993, placed my $3 purchase on the turntable and experienced something of a minor epiphany. This was an experience akin to listening to those Enoch Light demonstration albums of light orchestral music, in which the reverie of a bucolic fugue is suddenly broken with advancing timpani and galloping flutes, but with some of the best songs you’ve ever heard. It was effectively three Rubber Souls in one: the left version of ‘Girl’ with just guitar and drums, foregrounding just what a sensational sequence of chord changes drives it along; the right version of the same song, featuring little more than harmonies and John Lennon. The left version of ‘Norwegian Wood’, with just guitar and bass hanging off George’s sitar; the right version of the same song, with guitar and tambourine. and then, of course, the straight down the middle versions which put you at the centre of the event, immersed in Beatles.

I loved the damp, hair-raising proximity of the 2009 Mono Remasters, but did I love them more than the supposedly inferior version I’d heard 16 years previously? I’m not sure. But stereo can be unbelievably exciting. We experience that excitement at the cinema; if we treat it with respect on a record, why shouldn’t it be just as exciting? The answer, if last night’s playback is anything to go by, is that it is – and it’s a difference that’s immediately perceptible on the eponymous opening song. The terrain is suddenly wider, which means that the individual components appear to occupy more room without crowding each other out. I’ve no idea, technologically, how that happens, but it’s impossible not to notice it. George’s lead guitar sounds emphatic and aggressive, filthily distorted at times. "Ringo likes the fact that we can hear him," half-joked Martin, but his peerlessly supple drumming frequently steals the show: his hi-hat on ‘Getting Better’, his sublime rhythmic tremors, somehow both intuitive and counterintuitive at the same time. It’s loud, because – as Martin pointed out – The Beatles were loud; "they really dug in".

Somewhat self-deprecratingly, that was something that Martin said he’d failed to take into account when working on the mixes with 2008’s Love album. He admitted that in the pursuit of clarity, he had made ‘I Am The Walrus’ "sound like Steely Dan". You can hear the resulting lessons learned on this version of Sgt Pepper. Even ‘Within You Without You’ turns a dream into something approaching a stampede, and once again, leaves you boggling that less than five years had elapsed since ‘Love Me Do’. The harmonies on ‘Fixing A Hole’ are hypervivid and opaque. For me though, perhaps the biggest revelation was ‘Good Morning, Good Morning’ – which, in this incarnation, comes at you like a psychedelic light brigade, and all the more contemporary for it. Why had I never noticed, at this point, that virtually half of everything that Blur did between 1993 and 1995 is so abundant with the DNA of this song?

There were also glimpses of the unreleased material, some of which will be found on two alternate versions of the album: one of different takes and one of broadly "unplugged" versions, along with newly unearthed records: Paul alone at the piano doing ‘Penny Lane’ sounds an especially tantalising prospect. Could this stereo remix in time become regarded as a definitive version? I dare say we’ll always go back to the original mono recording for that. I don’t think Giles Martin would even disagree on that front. But I’ve long since stopped worrying about what counts as definitive with my favourite albums. There isn’t a version I’m not interested in hearing; an isolated instrument part I don’t want to hear; a light which doesn’t throw up something hitherto unknown to me. I can’t imagine what they’ll come up with for the 60th anniversary, but I’m already interested. As long as I’m alive, I can’t see that changing.