If it wasn’t for the American Forces Network and a chance encounter with Pink Floyd’s roadies, Manuel Göttsching might never have produced the solid run of game-changing albums he made in the 1970s and early 80s. From the mind-bending free psychedelia of Ash Ra Tempel’s self-titled debut to the astonishingly prescient proto-techno of his 1984 solo album, E2–E4, Göttsching consistently proved himself one of the most daring and innovative musicians in one of the most fertile periods for German music. As guitarist, composer, and live electronics pioneer, Göttsching expanded the minds of listeners and the sonic palettes available to the many artists he influenced again and again and again. But the seeds of that breathtaking creativity were sown many years earlier, in a West Berlin bedroom in the mid-1960s.

As a child, Göttsching would stay up late at night with the radio on, intoxicated by the propulsive rhythms of The Four Tops and the Temptations. He had always been “fascinated” by the piano that stood in the family parlour like some weird, dark piece of furniture that you mustn’t put crockery on. “But I was not allowed to play it,” he recalls, “because I was just too loud.” It was the songs he heard on the radio that urged him to pick up the guitar instead – even if, for many years, his guitar lessons were strictly classical music.

“Many people listened to the forces network radio station,” he recalls now, “that was the channel where you could listen to very different music that you would never hear in Germany. A lot of this music, though I found out only later, was black music. It was African-American music. I was young and I listened to it on the radio. I just loved the rhythms. This surely has influenced me, of course.”

The other decisive event came about a half decade later. By 1970, The Steeplechase Blues Band, Göttsching’s Cream-esque jam band with Wolfgang Müller and Hartmut Enke, had been rehearsing at the Beat Studio on Pfalzburger Strasse in Wilmersdorf. The studio was a hotbed of musical talent set up by the Swiss avant-garde composer Thomas Kessler. Alongside Göttsching’s early blues rockers, it provided a home, as well, to such seminal groups as Tangerine Dream and Agitation Free. “We went there two days a week, in the week time, afternoons,” Göttsching says. “So we had good ideas and we were very optimistic for the future.” But compared to their better known peers, they felt they lacked a certain edge. So Enke set off to England in search of new toys.

“At the time it was not possible to buy second-hand music equipment in Berlin,” Göttsching recalls, “and we were still going to school so we didn’t have money to afford new equipment.” It was the long cool summer of 1970. The Beatles had just split up and the Isle of Wight Festival, the biggest rock festival ever staged, was around the corner. Enke spent his days tramping up and down the Charing Cross Road and Shaftesbury Avenue, amazed at the sheer variety of gear on display in the music shops of central London, compared to a still-isolated Berlin. Making a decision – how best to spend what little pennies he and his friends had managed to scrape together – was nigh on impossible. Until his last day in town, when fate stepped through the door, wrapped in denim and four-day stubble.

“He was in one particular shop,” as Göttsching tells it, “and there came the roadies from Pink Floyd.” The Floyd’s tech crew were lugging in four huge WEM speaker cabinets. Set up in 1949, Watkins Electric Music was a British company founded by brothers Charlie and Reg Watkins. By the end of the 1960s, they were the go to choice for any band in search of serious volume. The Who had used WEM amps for their tours of 1967-68. The Glastonbury Festival used WEM. One year before Enke arrived in London, The Stones in the Park outdoor festival was powered by WEM and a few months later, Miles Davis’s electric band would be blasting through WEM cabinets at the Isle of Wight. Now here were Pink Floyd’s roadies, fresh off a run of European festivals, hoping to trade theirs in for something newer. “Wow!” said Enke, “This is great – I’ll buy it!”

There was just one problem. How was he going to get these four hulking beasts back to Berlin? It was like the old joke: How do you get four elephants in a Mini? Simple. Two in the front, two in the back. Enke hailed a cab. Evidently unaware of the logic of children’s jokes, they wouldn’t take four elephants on their own, so Enke hailed three more cabs and put one speaker cabinet in each one and sent them to Victoria station where the amps would be loaded onto the first freight train to Berlin. “And it worked!” Göttsching exclaims, still amazed. “From one moment to another, we had the biggest equipment of all the bands here. We managed to be the loudest band in Berlin.” They even got away without paying any customs duty.

When Göttsching and Enke, fresh back from London, rocked up to Beat Studio with their new gear, Klaus Schulze was just pulling up in his car. Immediately, he turned green with envy. The 22-year-old drummer had just left Tangerine Dream and was on the lookout for something new. When he saw those WEM amps piling through the studio load in doors, he knew he had to be a part of whatever sound they were making. “We must form a band,” Schulze said.

In that moment, Ash Ra Tempel was formed. “Our first small concert was two weeks later in Berlin,” Göttsching recalls. “Within half a year, we played nearly three times a week. We didn’t have any professional promotion. There were no music papers. No radio promotion. Just playing, playing, playing. Everywhere. After six months, everybody in Berlin knew about Ash Ra Tempel.”

I’m talking to Manuel Göttsching over a crackly Skype connection. “I’m not a big fan of Skype,” he admits. “I don’t use it very often.” He is sat in a loose grey sweatshirt, with a wan, pinched expression that occasionally cracks into a wry half smile. Behind him stands a seemingly wall-covering bookcase filled with box files and ring binders. As we speak, his fingers tap distractedly upon the desk in front of him. Somehow, he seems very far away – a feeling that the poor sound coming out of my laptop speakers only enhances.

But next week, Göttsching will appear at the Barbican Centre in London for the Convergence Festival. Hunched over a laptop and MIDI keyboard, he will perform a special live version of his legendary solo album E2–E4 before joining up with Ariel Pink, Shags Chamberlain, and Oren Ambarchi to play tracks from the Ash Ra Tempel albums Schwingungen and 7Up. With a wink to Göttsching’s childhood hero Jimi Hendrix, they will call themselves The Ash Ra Tempel Experience.

The group first came together just two years ago at the Supersense Festival in Melbourne. Festival curator Sophie Bruce suggested, alongside his solo set, perhaps Göttsching might like to take part in some workshops with a few other acts on the bill. Shags Chamberlain was there playing in Ariel Pink’s band. Oren Ambarchi was doing his usual swirl of heavy guitar drones, accompanied this time by drummer Joe Talia. Perhaps some sort of spontaneous collaboration could take place?

“I thought about it,” Göttsching muses. “I didn’t know any of them to be honest. Never heard of them before. But my wife proposed that we play some old Ash Ra Tempel albums.” Since he was to be joined by Ariel Pink, they proposed tracks from the group’s two vocal albums from the early 70s. “I wanted to send them the notes, the lyrics and the chords, and they said, no! We know it already! We don’t need that!” They had one rehearsal. Performed the next day. Recordings of the gig are to be released imminently. They went on to repeat the performance at a festival in Düdingen, Switzerland, and now London.

“It’s really fun,” Göttsching says of playing with the new quartet, “because I did not perform these pieces very often at the time. So this is really like something new. And then when I listened to the recording, it sounds like it could have been some lost rehearsal tape of the original group!”

Playing those licks once more, almost forgotten, has clearly put Göttsching in a reflective mood. “I don’t play so many concerts these days,” he tells me. “I’m not on the road. I don’t tour.” But he stills remembers the days when he played practically every other day, at every club in town. He remembers, too, the musical partnership that made it all possible. “The story of Ash Ra Tempel,” he says, “is really this whole story of Hartmut Enke and my partnership with him for many years, and all the different bands that finally led to Ash Ra Tempel.”

Friends since school days, Göttsching was still playing the acoustic guitar when he and Enke started their first band. “I was fourteen – or even thirteen,” he tells me. “In the beginning, we were doing the cover band thing. We played some songs by the Small Faces, The Rolling Stones, the Beatles.” As well as strumming the chords, Göttsching was also the singer. “It was funny,” he laughs “I didn’t know very much English at the time, so I was just trying to imitate the sound of English.” They would play at friend’s parties, Göttsching belting out phonetic interpretations of hits like ‘Gloria’ and ‘Get Off My Cloud’ with Enke backing him up. They called themselves The Bomb Proofs. “But we soon got a little bored playing this.”

They started to improvise. The tracks grew longer. Göttsching got his first electric guitar and quit vocal duties for good. “This was different,” he says, “completely different. We wanted to play our own music, to create our own music, and create our own structures.” Under the new name, Bad Joe, Göttsching and Enke started playing “completely free music, like free jazz or whatever.” It was, he admits now, “a bit chaotic.” What they needed was structure.

The inspiration they sought came from the Mississippi Delta, via Swinging London. Hooked on the raw musicianship of British players like John Mayall, Peter Green, and Eric Clapton, Göttsching and Enke changed their band name again. Now they were the Steeplechase Blues Band. But though the ‘blues’ provided the basic structure of the songs and the word itself sat there square in the middle of the handle, it’s unlikely that Alan Lomax or Harry Smith would have recognised in these long form freak-outs any real heir to the rural work songs and jug band shakedowns they had patiently recorded in the Deep South. Our two schoolfriends from Berlin had little interest in pursuing any real, authentic blues spirit. They scarcely even knew what such a thing was. Drawing on bootlegs of Jimi Hendrix playing live and the “free music” wig outs of their previous group, this was to be the blues extended, multiplied, and launched into space.

If the final leap away from the blues and into the cosmic sound we know today as Ash Ra Tempel came in 1970 with the arrival of Klaus Schulze, that ‘classic’ line-up would nonetheless be short-lived. Schulze would stay with the group for just one album before leaving to pursue a burgeoning interest in electronic music, releasing his dreamy solo debut Irrlicht barely a year later. After Schulze briefly rejoined for 1973’s Join Inn, Enke left too. “He didn’t want to play anymore,” Göttsching sighs. “He wanted to be free to play when he wants, what he wants, and not to be in the music business. And that was, of course, when I started my solo albums.”

1975’s Inventions For Electric Guitar, at once the last official Ash Ra Tempel album and Göttsching’s first solo venture, marks a dramatic departure from the Kosmische sound of the previous five years. It represents the first fruits of an obsession whose influence would determine the character of all of the producer’s subsequent records, up to E2–E4: the minimalism of Terry Riley and Steve Reich. Göttsching attributes the appeal of these composers’ works to the African-derived rhythms that Reich studied in Ghana in the early 70s and Göttsching heard on the radio as a child. “I loved this type of music,” Göttsching tells me, “so I thought, why not try something with electric guitar? Just with one electric guitar.” The resulting album has an austere beauty, anticipating, in many respects, Reich’s own Electric Counterpoint of more than a decade later.

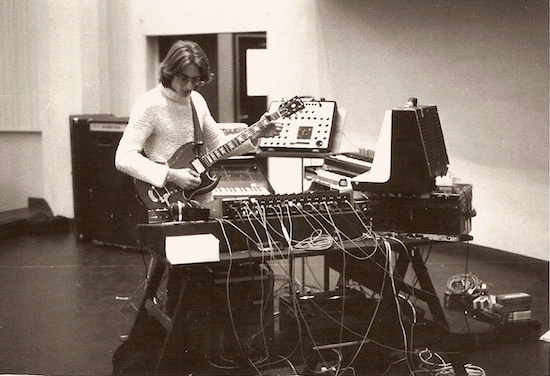

The end of the 70s was spent progressively developing a home studio set-up capable of allowing Göttsching to realise his increasingly expansive vision of minimalist music as a solo artist. “I was interested in electronics because I was doing it all alone,” he says. “So I built up the studio more and more.” He fell in love with the sound of the Minimoog, and later the ARP Odyssey synthesizers. Laying his guitar to one side for a moment, he composed the propulsive rhythms and shimmering chords of ‘New Age Of Earth’ on his growing collection of electronic keyboards. “But it’s all payed by hand,” he insists. “There was not yet any machine or any sequencer. I started to use that later.”

There followed a long period of hibernation. “I was playing sessions in my studio. Just playing every night, many times.” He recorded everything, amassing vast quantities of taped improvisations. “And finally, after many years, I recorded something like E2-E4. It’s a long development.” The magic finally happened in December of 1981. Göttsching had just got back from a fourteen-date European tour with Klaus Schulze. Tired after weeks on the road, he nonetheless resumed his regular schedule, sat down in the studio, and pressed record. One hour later, music had been changed forever.

One of the most extraordinary things about E2-E4 is that it took as long to record as it does to listen to. “I never did any overdubs, never edited anything,” Göttsching insists. “Just from the beginning to the end, it’s like this. It’s like a live recording. Everything was in the moment.” But from such modest beginnings, the album, finally released in 1984 on Schulze’s Inteam label, had a disproportionate influence. It sold modestly. Just a few thousand copies. But one of those copies made its way to the record bag of Larry Levan who made it a staple of his Paradise Garage sets. Later, Italian house producers Sueño Latino reworked it for the Balearic club scene and their version, a chart smash in several European countries, was remixed by Detroit legend Derrick May.

But Göttsching himself insists he never had any interest in dance music. Techno didn’t even exist when he recorded E2–E4. “There was a kind of disco music,” he recalls, “but I didn’t want to do anything like that.” He was amazed by its popularity amongst clubbers. “I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “I don’t know how to explain it.” As far as he was concerned, it was just the minimalism of Reich and Terry Riley played on electronic instruments.

And for a long time he was convinced the piece could never be performed live. “I thought that it’s not possible to perform because I used my whole studio equipment. I used all the synthesizers, the sequencers, the mixing desk, the reverbs. No chance ever to bring all this on a stage.” Only since the beginning of the twenty-first century, with the increased processing power of laptop computers and the development of software like Ableton, has a live version – like the one that will be performed at the Barbican – become a practical possibility. Since then, the possibilities of different realisations seem to have just kept on expanding. Göttsching tells me about versions of the piece performed by jazz orchestras, classical ensembles, a possible ballet in the offing. “It’s not only for clubs, for DJs, or for dancing,” he says. “It’s going in various directions. That’s really what interests me.”