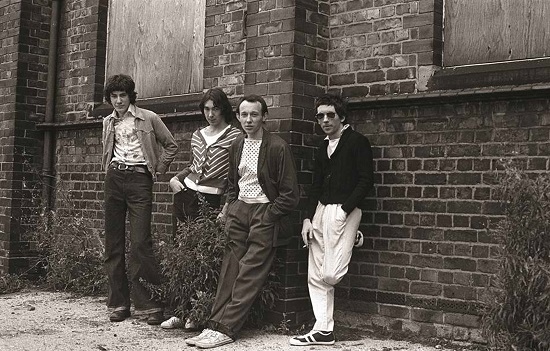

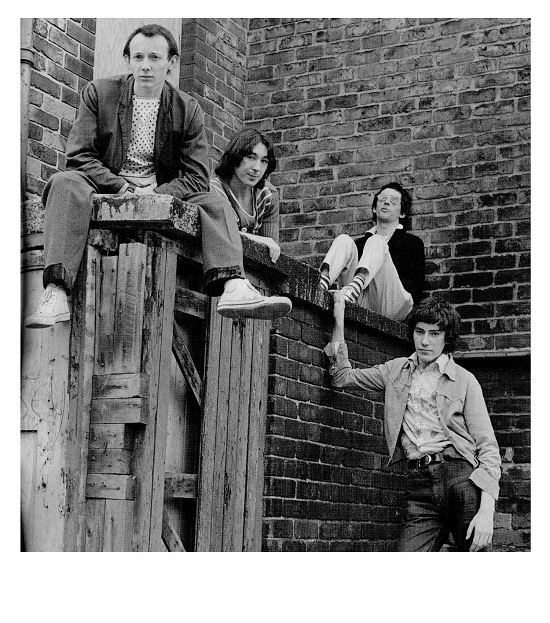

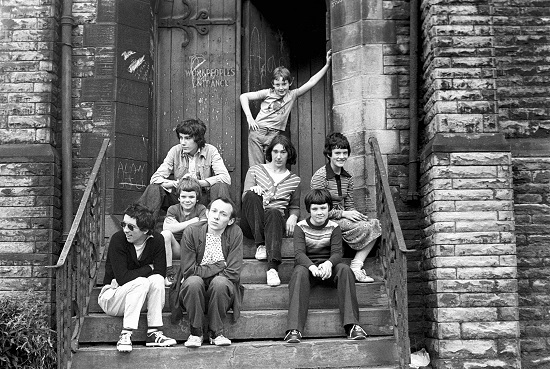

Photographs by Phil Mason

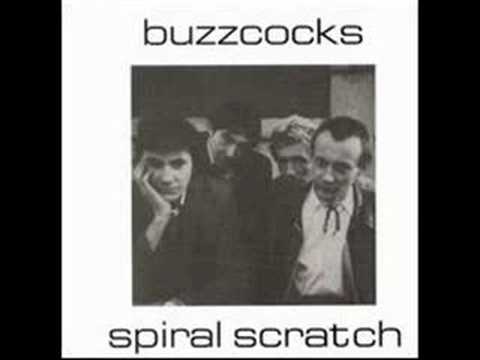

Spiral Scratch is the kind of record it’s easy to romanticise. It was recorded in relative obscurity during studio downtime by a then unknown Martin Hannett, funded by money borrowed from friends. While The Sex Pistols’ ‘Anarchy In The UK’ came out on EMI and The Clash’s ‘White Riot’ was released on CBS, the Buzzcocks’ debut was something else entirely: a run of just 1,000 copies released on their own specially created New Hormones imprint.

There had been independent releases before this point. The nascent days of rock & roll were boosted immeasurably by the likes of Sun Records, for example. Even punk progenitors Stiff and Chiswick were indies that had been formed by London music business regulars in the mid-70s. But where those labels were still tied to the industry at large and run by (at the very least) semi-professionals, New Hormones was the work of enthusiastic self-starters who could see no other option for releasing their music. The label offered a demystification of the notion that records were some kind of mysteriously produced artefact; this was a hitherto unseen demonstration that ‘anyone’ could do it.

As the band’s then-bassist Steve Diggle puts it, "Before that it was like EMI had some divine, mythical right to print this mysterious black vinyl stuff and no one else was allowed. There was always somebody in town who could make you a table, bake you a loaf of bread or fix your car, but you never knew a bloke down the road who could make you a record." It could be said that New Hormones was a key extension of the famous Sideburns fanzine cover: "This is a chord, this is another, this is a third, now form a band", one of the purest articulations of punk’s DIY aesthetics, the direct inspiration for a swarm of indie labels that followed.

That Spiral Scratch can be seen as something of a landmark isn’t lost on Domino Records, who have just reissued the record on this, its 40th anniversary. The EP, as their liner notes read under the heading ‘The Most Important Record Ever’, "was more important than The Sex Pistols’ ‘Anarchy In The UK’. More important than The Damned’s ‘New Rose’. More important, even, than The Ramones’ first album […] It is a celebration of that ‘can-do’ spirit – illustrating the power of unharnessed teenage energy and naivety achieving so much with so little resources, and providing the inspiration to young people of their, and every other subsequent, generation." It is easy to argue, then, that it is on Spiral Scratch that the punk ethos was at its most flawlessly articulated.

"The ‘punk ethos’? That’s cute," laughs Richard Boon, the band’s manager at the time and the founder of New Hormones, when this hyperbolic reading of Spiral Scratch’s legacy is proposed to him. "No one really knew what they were doing, Martin Hannett included." Easy as it is to eulogise the record’s longstanding virtues, the reality of Spiral Scratch is that when the band entered the studio on December 28, 1976, they simply wanted to see what they sounded like before the punk scene passed them by.

"We didn’t think there’d be any future," remembers Pete Shelley, then the group’s guitarist. "At that time it looked like the gig was up, that people had found us out and the whole punk thing was just gonna die a death." The Sex Pistols’ Anarchy Tour earlier that month had been something of a shambles, with gigs cancelled left, right and centre in the furore of the band’s infamous Bill Grundy interview, and as Shelley continues "The impending thought was that this could all be over quite soon. That was the motivating factor. We wanted to make a record just to say ‘this actually existed.’"

The notion of Spiral Scratch as a grand punk statement against the major labels came later. At the time an independent release was simply the fastest way to make that mark. The idea, in embryonic form at least, belonged to Martin Hannett who was then ‘Martin Zero’, the group’s ‘agent’ and a would-be producer. Shelley recalls, "We’d go round to his office and sit there drinking tea. He wanted to be a record producer and he hatched this scheme where he was going into the studio producing this band then in the evening when they’d gone home we’d use the studio and then do our record. All those initial plans fell apart, but the more we found out it was doable, it carried on with its own momentum."

Just how long the session actually lasted depends who you ask. It was a couple of hours, says Diggle, just 30 minutes, says Boon. As the former tells it, "We just blasted it out and then went to the pub. There was no time to think ‘we’ll mic up this’ or anything, there were no thoughts of ‘we’re making a wonderful record’, it was in and out. The guy that worked there wasn’t used to that, with recording he thought you’d be getting a drum sound for the first four hours, then the bass, then the guitar and all that. We just set up quickly and away we went. We didn’t want to be there long."

"You can see it as either a stroke of genius or a stroke of necessity," he continues. "Initially it was the second, it was made out of necessity, but it did become a stroke of genius." "We weren’t stupid enough to think ‘that’ll show [the major labels],’" adds Shelley on their slight to the majors. "It was just the only way that we could do it."

That’s not to say, of course, that the statement Spiral Scratch made was merely a happy coincidence; an accidental stroke of genius. However casual its conception, the potency of the Buzzcocks’ recorded alienation was as strong on that EP as any of punk’s other formative records; one has only to listen to a song like ‘Boredom’ to feel the intensity of disaffection the band bore.

"Progressive music was losing its way. The landscape was barren at that time, the imagination had gone out of everything and [Spiral Scratch] woke up your senses. It was an assault, it woke up your consciousness, gave you some realisation of who you were and what music was doing to you," says Diggle. Further still, as Boon argues, Manchester, like much of regional England, was not enjoying the fruits of punk’s nascent ascent as much as London. "We wanted to be distinct and not in the context [of London]," he says. "It had nothing to do with all that London music industry stuff that was really behind a lot of the punk acts, it was about avoiding all those clichés and actually making the regions important. Manchester was really drear, most of the regions were, there was nothing to do, there were no bands, it was just Bowie kids and a couple of hair metal bands and nothing that reflected really what was happening."

There was a sense of humour to Spiral Scratch too, which as Shelley points out was sorely lacking from the mid-70s. "There was all this big, bloated prog rock. I don’t know which of Henry VIII’s wives Rick Wakeman was doodling away about with his big high spectaculars, but where was the fun bit? Getting together, getting drunk and playing music?"

Hannett’s production, even at his most inexperienced, was somewhat groundbreaking too, remembers Diggle. "Any time the engineer was doing something that sounded right, Martin Hannett would undo it and started messing with everything. The engineer was furious but he ended up getting that unique sound, the ‘terrible beauty’ as I call it. On the one hand it sounds terrible and on the other it sounds beautiful. It’s a very unique sounding record and that worked hand in hand with the nature of the songs and the punk nature that came out of Buzzocks at that time, the production as much as the songs and what we were saying."

The band pressed 1,000 copies of Spiral Scratch, the smallest number possible, with the intention of simply selling enough at their gigs to pay back a hastily assembled bunch of financial backers – mostly family members and old teachers – that had helped them scrape together the £600 it took to press. As for their expectations, Shelley continues, "we had no vision for the future because we didn’t really think there was going to be one." Checking each copy by hand, each of the original run was accompanied by a leaflet: "This is almost certainly going to be a limited edition release. There won’t be much advertising."

Diggle’s memories of packaging and poring over each record for scratches and ink stains, which took place in a warehouse full of washing machines, are hardly imbued with the frantic excitement of a band on the cusp of revolution. "I just thought ‘so that’s what 1,000 records looks like.’ After [packaging] a few we just got this feeling of conveyor belt alienation." The celebratory drinks that followed – two bottles of cheap Spanish wine and then a couple at the local pub – were to mark the end of that monotony as much as the birth of one of punk’s founding cornerstones.

"We had no expectations at all," says Boon of the feeling once the shift in the warehouse was over. "Fingers crossed we could just pay people back." Yet Spiral Scratch turned out to be something of a minor sensation. Convincing their friends at their local Virgin record shop to stock the EP, as well as Geoff Travis of Rough Trade, then a mail-order service, the original run sold out in just four days.

Fortunately, as Shelley recalls, the door that seemed to be closing on punk had been thrown wide open again by renewed press interest: "When we went in to record it looked like that was it, there wasn’t all that much interest. Even the Clash weren’t signed and only The Sex Pistols and The Damned had records out. There was no reason to think [punk] would rise like a phoenix from the ashes and be a voice of rebellion for generations to come. Then [once Spiral Scratch was released] there was this new thing that everyone was interested in, called punk. It used to be a few articles in the weekly mags, now it’s the number one rebellion."

The EP eventually sold 16,000 copies. Howard Devoto, the band’s original frontman who sang on Spiral Scratch just to depart in its wake to finish his degree at the Bolton Institute of Technology and then on to form Magazine, said: "I just don’t like movements. I’m just perverse." He told NME a year later: "Punk felt like a cult thing originally… what went wrong was that it caught on." With the beginnings of punk’s occasionally self-parodying, yobbish second wave, it lost what he called its ‘negative drive’, the impetus on "constant change, avoidance of stale conceit, doing the unacceptable."

Devoto’s departure led to Shelley moving on to lead vocals and Diggle from bass to guitar.

Suddenly, as Shelley points out, "all the major record labels were going ‘we need a punk band’ and signing up anyone who had short hair and straight legged trousers. It became very popular." The Buzzcocks were naturally courted by every imprint in the land, and as romantic as it would have been to continue their independent stance with New Hormones, they soon signed with United Artists, which soon became part of EMI.

There was no talk of ‘selling out’, however, as there had been with The Clash’s infamous £100,000 CBS deal signed shortly beforehand. As Diggle puts it "We’d never signed up to be a record company, we didn’t know how to run a label, we got into it to make music and say ‘fuck off’ to the world. It was supposed to be a blunt statement then suddenly you’re an A&R man." Furthermore, any profits made from Spiral Scratch had been all but drained by The Buzzocks’ place on The Clash’s ‘White Riot’ tour, where they were bereft of their bill-mates’ major label touring fund.

Boon claims he was persuaded by Bernie Rhodes to have meetings with CBS too, but they and many others were turned down for their lack of understanding of just how important creative control remained to the Buzzcocks. The test, Shelley says, was to tell the fleet of A&R men that had begun to appear at their gigs that their next release was to be ‘Orgasm Addict’. "Most people’s interest just seemed to dissolve after that, they thought ‘we’ll never get this played on the radio’, although one person stuck with it, Andrew Lauder at United Artists. We said, ‘Well, we want control over what we do. We don’t want to be your punk band, we’re a punk band in our own right.’ It was a business transaction, we weren’t giving away anything, we still had the control over what we did and how we did it. ‘Orgasm Addict’ was never played on the radio, and he didn’t care."

New Hormones would continue, the label’s next release being a fanzine-esque collection of collages and artwork by Jon Savage and Linder Sterling, The Secret Public, and later more musical pressings by the likes of Sterling’s band Ludus, Acton post-punk sextet The Decorators and Andy Diagram’s Diagram Brothers amongst others. Yet for the Buzzcocks, though they maintained creative control at United Artists, their statement had been made.

Whether or not New Hormones was the first truly independent label is up for discussion – Throbbing Gristle’s Industrial Records started in 1976 for example – but its legacy is not. "I hate that whole debate of ‘well so-and-so did this [before you],’ and of course all the American labels started out as local indies, but [we were still] finding out how to do it," says Richard Boon. With Spiral Scratch the Buzzcocks demystified the printing process, and were a direct inspiration to the immediate surge in indie labels that followed. As author Simon Reynolds puts it in his book Rip It Up And Start Again: Post-punk 1978-84, New Hormones was "not the first independently released record (not by a long stretch) but it was the first to make a real polemical point about independence. In the process, Spiral Scratch inspired thousands of people to join the do-it-yourself, release-it-yourself game."

Perhaps the most important legacy of Spiral Scratch, was to extend the community of punk beyond London. Just as The Sex Pistols had inspired legions of punks to form their own bands, the Buzzcocks extended that philosophy to the record release process, particularly for those not fortunate enough to have London’s music industry on their doorstep. Boon illustrates, "There was a record shop in Newcastle who’d ring to ask if we had any gigs coming up for their band and we’d set up a gig then they’d reciprocate. That was the beginning of a kind of colloquial network for people who were similarly minded."

"There was a load of weird people all over the country, even if they were just on their own, it allowed them to think ‘this is something I can do,’" adds Shelley. "I think it’s like an art movement because it starts off with an idea, rather than having to be in a certain place. People tend to gravitate together, you see people at punk gigs then a week later they’d have their own band because it was that easy to do. I think a lot of people don’t do what they dream of doing because they think people can find them out, but nobody found us out."

Perhaps, then, with the internet’s abundance of indie labels and self-releases a defining characteristic of the modern musical landscape, Spiral Scratch really was ‘the most important record ever made’, though even the Buzzcocks themselves would find it hard to argue that that was even remotely intentional. "There was no grand vision. It was supposed to be the most uncommercial form of music we could imagine," Shelley surmises. "We went out of our way to make it difficult, but now it’s become a cultural icon. That’s quite a rarefied place to be, not where we intended to get to. There’s only ten minutes of music!"

The 40th anniversary edition of Spiral Scratch is out now on Domino