“All the bankers gettin’ sweaty beneath their white collars /

As the pound in our pocket turns into a dollar.”

Margaret Thatcher was arguably at her most powerful in 1986, and there was a sense at the time that her indomitable grip on the nation would last forever. During the seven years she’d been in power she’d defeated the miners, retained the Malvinas and allowed Irish hunger strikers like Bobby Sands to starve to death. She’d abolished the GLC, set about privatising public utilities like British Telecom and British Gas and assisted Reagan’s bombing of Libya. The ‘special relationship’ was now a euphemism for the UK acting in accordance with US foreign policy come what may. What’s more, Thatcher was on the cusp of winning a third term in 1987, with only a slightly reduced majority, a feat that hadn’t been achieved by another administration since 1820. Nobody could have foreseen her being “stabbed in the back” by her own ministers four years later, but Thatcherism has endured beyond her political career, and its legacy perpetuates, transmogrifying into the spectre of Neoliberalism.

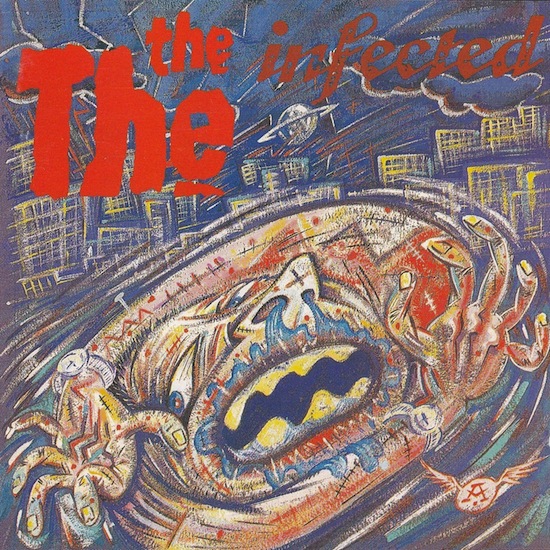

Perhaps most significant to our times – and to little fanfare back then – was the passing of the Financial Services Act on October 27 1986, incidentally three weeks ahead of the release of The The’s Infected. Dubbed the financial “Big Bang”, the London Stock Exchange was finally able to throw off the shackles of regulation, soon ensuring the English capital would become the global cynosure of big business. This “radical Thatcherite reshaping of the City” – said The Guardian in 2011 – was “a period in which the Americans arrived to snap up ancient City institutions for huge premiums, leading to the clubby atmosphere of the Square Mile being replaced with the rapacious, bonus-grabbing culture of the investment bank.”

The music community’s opposition to the incumbent Conservative government was strident but ultimately ineffectual. Opprobrium came in various forms: frustration at three million unemployed on The Specials’ ‘Ghost Town’ (“Government leaving the youth on the shelf”); anger at the Falklands War on Crass’ ‘How Does It Feel?’ (“How does it feel to be the mother of a thousand dead?”), and plenty of spite (focused and unfocused) on ‘Tramp Down The Dirt’ by Elvis Costello and ‘Margaret On The Guillotine’ by Morrissey.

Red Wedge also came into being in 1985, formed by Billy Bragg, Paul Weller and Jimmy Somerville, with a Live Aid-style assemblage of pop luminaries championing the Labour Party with concerts and plenty of vocal support in the media. The The actually went on tour during Red Wedge’s second wave of shows in 1987 alongside Captain Sensible and the Blow Monkeys. But – as Beyoncé, Jay Z and Katy Perry’s championing of Hillary Clinton in the United States recently proved – celebrity political endorsements from high profile musicians will only get you so far.

Infected might have been steeped in foreign and domestic affairs, but Matt Johnson’s previous album, Soul Mining, had been more personal than political, earning The The its own genre tag: the existential blues. Where so much synthpop was icy on the exterior, Johnson’s felt visceral but familiar, looped repetitively while he burrowed into the sonic melange of his own anxieties. Back then he was often accused of “psychobabble” in the music press, but time has been kind. Retrospectively hailed as a “hidden masterpiece” by Garry Mulholland in his 2006 book Fear Of Music, Guardian critic Alexis Petridis expressed incredulity that Soul Mining had nevertheless dropped out of public view and off the critical radar when it was reissued in 2014. He did concede however that Johnson’s legacy was safe in the hands of dance music: “If no hip young band or singer-songwriter drops his name, there’s been a plethora of unofficial re-edits of Soul Mining’s closing track, Giant, in recent years.”

Despite its lack of frontline attention, Soul Mining is a recherché treasure trove of impassioned songwriting, spoken about in hushed whispers, usually by men in their early forties in Nitzer Ebb t-shirts. What makes it even more remarkable is how world-weary the lyrics are coming from the pen of a 22-year-old. “You could have done anything if you wanted,” Matt Johnson sings on ‘This Is The Day, “and all your friends and family think that you’re lucky / But the side of you they’ll never see / Is when you’re left alone with your memories." The song expresses some hope in the chorus, but the disenchantment in the verses is almost too much to bear.

On ‘The Sinking Feeling’ it gets even bleaker still: “My memory my fond deceiver / Is turning all my past into pain / While I’m being raped by progress / Tomorrow’s world is here to stay." Then he asks “How can anybody know me when I don’t even know myself?” over and over at the outro of the aforementioned ‘Giant’. On Infected he would mitigate the navel-gazing, and deflect his censure towards external sources, namely the British and US governments.

I was blown away the first time I was exposed to Infected in 1986. As a 13-year-old Marillion fan, I had to concede it sounded like nothing I’d ever heard before. My older brother, who was going through his Patrick Bateman phase, was playing it in his car on a dynamic set of speakers. He would usually be listening to Squeeze or Japan, so this new confrontational cacophony made me sit up and take notice. It had an intensity that wasn’t altogether pleasurable. The crisp, emphatic percussion on the title track transfixed me, while the invective throughout scared me a little bit if I’m honest. Then there was the bold seediness of ‘Out Of The Blue (Into The Fire)’ that graphically recounts an encounter with a prostitute. I wasn’t even sure if I was old enough to be listening to this stuff.

I lost touch with the album for a long time, but then a few years ago, I was in a record shop in Dublin where it was playing loudly on the PA once again. I remember feeling that same tingle of excitement that I’d experienced all those years ago, and I was agog at the fact it still sounded so peerless after all this time. A lot of music from the mid-80s hasn’t aged well, but Infected is fresh and magnificent still, and the production – by Johnson and Warne Livesey – is breathtaking. I had the very vinyl that was playing in the shop taken off the turntable there and then. I whisked it home and we rekindled our awkward relationship. I’d changed but Infected hadn’t. Or maybe the dystopian mise-en-scene of May’s Britain is just a creepy simulation of Thatcher’s Britain 30 years on, rendering the record’s modus operandi as applicable now as it was then. Have we come full circle then?

“We have, with the situation in the Middle East, the continuing Americanisation of Britain, a right wing government in power,” Matt Johnson told The Crack earlier this year, “so there are a lot of parallels between 1986 and 2016.”

In September, the ICA celebrated 30 years of the album by screening Infected: The Movie, an innovative video collection made at the time to enable promotion of the record without The The having to tour. It preceded Beyoncé’s visual album – despite claims to the contrary about uniqueness – by roughly 27 years. Stevo from Some Bizarre somehow managed to convince Sony to part with £350,000 – a lot of money in those days – to make a promo for each song of the record; impressive considering The The was regarded as a cult act at best. Films for each song were hitherto shot in exotic locations such as Peru, Bolivia, New York and (the not quite as glamorous) Greenwich Power Station with four directors, including long-term Cure promo director Tim Pope and the late Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson. Tom Wilcox, associate director at the ICA, had initially spoken to Johnson about putting on a politics in music exhibition. The The The frontman thought a 30th anniversary showing would be appropriate, as the film hadn’t been shown elsewhere in all that time, and Infected was without doubt his most political offering.

“Matt’s prescience in terms of his political analysis, where he’s talking about radical Islam and American foreign policy,” said Wilcox, “you could be saying the same thing today, and in fact not many people were saying that in 1986”.

Indeed while Sting was offering up woolly rhetoric about Russians loving their children, Johnson was anticipating American involvement and the bloodletting that was to follow in the Middle East. To the repetitive chant of Arabia, Johnson navigates the skies in the guise of a GI Joe, giving us a visionary take on a geopolitical situation that was to get truly ugly. “This is your captain calling,” he sings on the mighty ‘Sweet Bird of Truth’, “with an early warning”. In the verse he crows about “all the money I’ve made / bodies I’ve maimed” and it’s difficult to ascertain if its a boast or a lament. It’s fair to say he was way ahead of the curve. (‘Armageddon Days Are Here (Again)’ in 1989 could be regarded as the sequel to ‘Sweet Bird Of Truth’. With its “Islam is rising, Christian’s mobilising’ line, it was held back as the first single from Mind Bomb with the Salman Rushdie affair still very much all over the news.)

Uncle Sam is cast as “the devil” on ‘Angel Of Deception’, who’s “stuck his missiles in your garden and his theories down your throat”. Johnson maintains he was never anti-US but anti-US foreign policy, and as a resident of New York these days, that certainly seems likely. The iconic “This is the 51st state of the USA” refrain on ‘Heartland’ still resonates, and is quoted by people who’ve never heard of The The. On ‘Heartland’, Johnson is at his most withering, describing “piss stinking shopping centres” and a “land of red buses and blue blooded babies”.

Then there are the lines: “So many people can’t express what’s on their minds / Nobody knows them and nobody ever will / Until their backs are broken and their dreams are stolen / And if they can’t get what they want then they’re gonna get angry!” It might have been written about the disconnect between politicians and the public in 1986, but it could just as easily have been written this year about Britain leaving the EU. Johnny Rotten once told Matt Johnson that Infected was the most spiteful record he’d heard in a long time; high praise indeed!

Infected isn’t just about politics; being The The, the human condition and all its frailties are exposed with admirable candour. If musically there’s a lustre, then the underbelly is riven with lust, and in keeping with the times, it’s all consumptive. From the feverish opener and title track to the final words of ‘Mercy Beat’ (“I was just another western guy with desires that couldn’t be satisfied”), insatiability and often squalid desire run through its very core. “From my scrotum to your womb, your cradle to my tomb” Johnson roars on ‘Infected’, with the chorus undoubtedly referencing the HIV epidemic that was at the forefront of most people’s minds at the time (“I can’t give you up til I’ve got more than enough / So infect me with your love”). “She was lying on her back with her lips parted / squealing like a stuck pig” on ‘Out Of The Blue (Into The Fire)’ is as brutal and as evocative as any image on the album, and whether a roman-à-clef or the assumption of a character, it’s worthy of the most celebrated of Beat writers.

But final word should go to ‘Heartland’, that feels more pertinent to our times than it did on its release 30 years ago. The frustration, the hopelessness, the despair… it’s all captured in its elegant and erudite five minutes. One thing doesn’t hold true. “The cranes are moving on the skyline” [my italics], though only to erect endless phallic monuments to capitalism rather than knocking the town down. But the bankers – with infinitely more power and cash – are still getting sweaty, and the pound in our pockets may yet turn into a dollar (or worse) when Article 50 is finally triggered next year.

“Here comes another winter of long shadows and high hopes /

Here comes another winter waiting for utopia /

Waiting for hell to freeze over."