This feature was originally published in 2016 to mark the album’s 25th anniversary

Three weeks before almost jumping the shark only to land in its jaws by opening for U2 on a disastrous stadium tour, Pixies made one of the more curious U.S. network television debuts on February 6, 1992. Coyly assembled around ‘It’s Raining Men’ co-writer Paul Shaffer and his house band as musical guests on Late Night With David Letterman, Black Francis, Kim Deal, Joey Santiago and David Lovering were on the limping last leg of promoting their fourth full-length studio album, Trompe Le Monde (“available now on the popular CD format,” Letterman enthused). Of course, this was a huge deal – a real coup – but with drummer Lovering reduced to maracas and Deal blankly strumming an acoustic guitar on a breakneck version of their latest record’s title track, the internal strain couldn’t be hidden behind the awkward smiles. In a few short months, Pixies were no more.

Stripping that performance of its doomed backdrop (and purging all memory of Shaffer’s frankly masturbatory organ solo while we’re at it) even a cursory listen to the studio version of ‘Trompe Le Monde’ today reveals a band thriving beyond any consideration for limitation. With Francis’ perfectly senseless lyrics ("Electrically played for outer space and those of they who paid…") marrying with bold tempo shifts and quasi-metal guitar shredding by Santiago, it’s a dizzy blitz of rock bombast that sees Pixies’ alchemical force gleam into sharp focus. Though very briefly tainted by pastiche on prime-time U.S. television that night in early February 1992, ‘Trompe Le Monde’ fares microcosmic of a 15-track dénouement the sheer urgency, pop potency and genre-warping unpredictability of which emphatically checks out 25 years later.

Whilst riding a surge of acclaim following the cult success of the game-changing, Gil Norton-produced Doolittle, cracks that would soon eventually reveal a Kim Deal-shaped hole in Pixies’ final years began to surface in June 1989. With Francis having reportedly thrown a guitar at the bassist at a show in Stuttgart, Deal refused to play at Frankfurt’s Batschkapp three nights later. “We found her hanging out in her hotel room, with no intention of playing,” Joey Santiago said in a 1997 interview with Mojo. “But our lawyer convinced us to try and work it out – to give her a warning or something.” When they fulfilled their globetrotting touring obligations in New York at the end of the year, the band were totally burnt out. A hiatus was promptly called, The Breeders – who Deal had formed earlier in the year – recorded their debut, Pod, in just two weeks with Steve Albini in Edinburgh and the rest of Pixies relocated to Los Angeles to map out Bossanova, a space-obsessed, surf-soaked departure that bore the imprint of psychic fatigue stemming from Pixies’ gruelling schedule of 1989.

When album number three hit the shelves to a relatively lukewarm response in August 1990 (“a pretty far cry from its predecessor”, Moira McCormick of Rolling Stone said), it was commonplace for the band to deflect from the tensions that were further pushing Francis and Deal into different worlds. In an interview for the same magazine in November that year, Francis told Michael Azerrad, "From what I hear about other bands, I think we argue among ourselves very little. We tend to get along just fine. We’re all sort of pleasantly mismatched. And it’s kind of nice.” With Deal flourishing in her own realm and every original track on Bossanova – slickly produced by Norton once more credited to Francis, the collaborative chutzpah that defined Come On Pilgrim and the all but sacrosanct Surfer Rosa had wilted to virtual non-existence. Having raged against the dying of the light for a couple of years, the scene for Pixies’ boldest statement and early 90s alternative rock’s inexorable flameout was set.

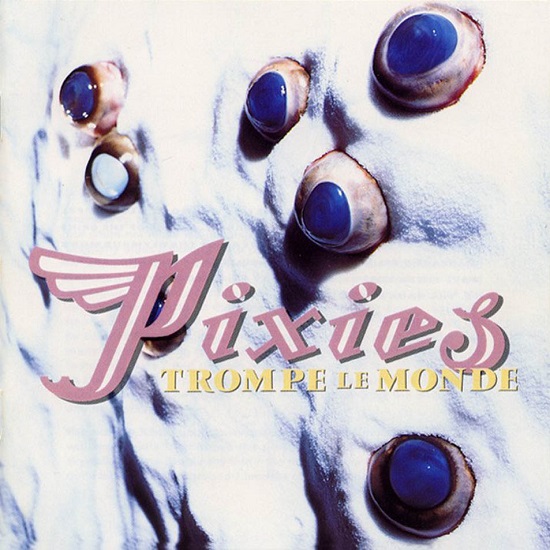

With the four records preceding it amongst the most canonised of the era – each a masterful exhibition of feverish and brilliantly bastardised rock & roll – Pixies had long achieved the sonic equivalent of collective self-actualisation by the time they reunited with Norton to record Trompe Le Monde (translated from the French phrase meaning “fool the world”) in early 1991. Inhabiting the no-mans-land between self-implosion and commercial breakthrough whilst straddling a rare thin line between the accessible and impassable, the occasion had come for glaring contrasts to meld on a release that never once pauses for a second to consider its own incongruity. Though returning to the brazen Sturm und Drang of their earlier output on several tracks, Trompe Le Monde also burst forth with slick, forward-moving momentum. In subverting the implied criterion to be one or the other – brash or sweet – Pixies decided to be both and more.

Although sequentially listening to the first two seconds of each of its 15 tracks offers ample confirmation in itself, nowhere is the rampant urgency of Trompe Le Monde’s 39 minutes in fiercer form than on ‘Planet Of Sound’, a two-minute throwdown in which Francis’ larynx-shredding scream and Deal’s muscular bass blend in triumphantly fucked-off fashion. Despite nearly having its legacy single-handedly disarmed by Dannii Minogue calling it “a crock of shit” in Smash Hits upon its release, it’s a warped tale of cosmic wanderlust in which any misgivings about Pixies’ ability to brace as a unit on their final lap are quickly shelved. Featuring some of Santiago’s finest lead freakouts, no sooner does the album’s first single screech to a close than the spectacular ‘Alec Eiffel’ offers up a mantra-like digression of equal intent. “Oh Alexander, I see you beneath the archway of aerodynamics,” Francis and Deal incant in unison above session musician, ex-Captain Beefheart and Pere Ubu member Eric Drew Feldman’s sorcerous synth-lines. Five minutes and three blazing songs in, it’s clear solemn contemplation isn’t high on the agenda.

From the hardcore squall of ’The Sad Punk’ and their exultant re-imagining of Jesus and Mary Chain’s ‘Head On’ to the aforementioned opening triptych and ‘U-Mass’ – a bona fide Pixies classic whose guitar riff was written years before at the University of Massachusetts – Trompe Le Monde’s relentless introductory ambush makes a significant challenge to Doolittle as the band’s strongest ever Side A. Doubling up as a tripped-out, lightning fast jaunt through the front man’s mind, it’s an unapologetic salvo aiming for maximum impact. In striking a keen balance between pure punk rock aggression and deceptively accessible hooks, the first half of Pixies’ swansong is, as Francis’ mishmash of knowingly gratuitous lyricism attests to, a release that puts the music – not words nor meaning, context nor any supposed impetus – first. As he put it in an interview with the Phoenix New Times a month after the release of Trompe Le Monde in October 1991: "To me, it all comes down to songs, guitars and electrical power. You plug in and play. And that’s it."

If Come On Pilgrim was Pixies as punk rock band, Surfer Rosa was Pixies as bizarro alternative heroes, Doolittle was Pixies as Pixies and Bossanova was Pixies as surf rock cosmonauts, Trompe Le Monde was – for all its abrasive juxtaposition and madcap tangents – the sound of Pixies as pop band, or at least insofar as a bunch of outsiders that just wanted to rock out in sunglasses could be a pop band. Almost giving Dannii Minogue a run for her money, ‘Bird Dream Of The Olympus Mons’ and ‘Motorway To Roswell’ are textbook cases in point. Where the former is a pristine slice of emotionally-charged guitar pop (and arguably one of the band’s most underrated songs) the latter is a sublime ballad that takes the myth of an alien spacecraft crashing at Roswell, New Mexico in 1947 and re-frames it from the lonesome perspective of the extraterrestrial visitor. With Feldman’s wistful piano lines beautifully entwining with Santiago’s braying double-bends at the end of ‘Motorway To Roswell’, the legendary spirit of Francis’ more wonderfully-woven and soberly articulated thoughts – as heard on ‘Ana’, ‘Havalina’, ‘Caribou’ and others before it – takes center-stage once more.

But to the elephant in the room.

Despite 3% of Pixies’ discography being credited to the bassist when Francis famously broke up the band via fax in January 1993, Deal’s absent songwriting credit on Trompe Le Monde – and indeed Bossanova – still speaks volumes. “He (Black Francis) definitely didn’t want her to have a big imprint on the songs,” Gil Norton later revealed, adding that Francis vetoed one of Deal’s songs that the producer deemed a cert. “She’s hardly on [the] album singing, which I thought was such a sad waste of such a talented voice,” Norton added. Apart from brief, disembodied flickers on ‘Subbacultcha’, ‘Alec Eiffel’, ‘Palace Of The Brine’, ‘Space (I Believe In) and closer ‘The Navajo Know’ the scarcity of Deal’s vocals – long a surefire Pixies’ hallmark – remains one of Trompe Le Monde’s few shortcomings. On the upside, that dearth only serves to underscore her vigorous bass playing – vital and inimitable as always – throughout.

But the tendency for some to demarcate Trompe Le Monde as essentially Francis’ first solo album in the guise of Pixies often readily neglects the fact that its strongest suit is its collective musical cohesion, from the first toying notes of ‘Trompe Le Monde’ to the whooshed expiration of ‘The Navajo Know’. With Norton’s tight, polished sheen lending the album an almost Technicolor veneer (very much still a moot point for some, particularly when framed with Albini’s raw and vibrant tact on Surfer Rosa), whether you look to the counterpoint melodies and layered vocals of mid-album peak ‘Letter To Memphis’, the psychotic, swaggering interplay of ‘Subbacultcha’ – a track that was originally demoed in their first studio session back in 1987 – or the ridiculously tight frenzy of ‘Space (I Believe In)’, Pixies bowed out whilst traversing power pop, space rock, wanderlust punk, theatrical glam rock and plain old alternative rock as a band boldly, if not exclusively, united by the music.

Comprising even its most manic, dense and outlandish elements, Trompe Le Monde is both Pixies’ purest pop triumph and most daring release. Notwithstanding the very real personal issues that ensured it would be the original line-up’s final full-length studio release, it remains a restless purge of aggression, melody and unwavering immediacy that saw Pixies’ celestial voyage explode in a supernova of sound and not the hushed whine that general consensus might lead one to believe. Reflecting on his abrupt dissolution of the band in early 1993, Francis later told Spin: “There was no closure – I’ll give them that. But it’s better than having some big fight or someone quitting the band and putting out a couple of shitty records with a different lineup, getting into some kind of legal squibble. It was sort of like, ‘Fin.’” While the jury is still very much out on the “shitty records with a different lineup” bit (Head Carrier, the band’s sixth studio album – and first full appearance with Deal replacement Paz Lenchantin on board – is released on 30 September) Pixies’ “Fin” wasn’t an impulsive fax, big fight or legal squibble: it was unequivocally Trompe Le Monde. Have a fresh listen, Dannii Minogue. I think you’ll be pleasantly surprised.