On June 5, 1989, Judge Robert Sklodowski of Illinois’ Cook County Circuit Court ordered Chicago pastor T.L. Barrett to turn over the title to his church, the Life Center Church For Universal Awareness on 5500 S. Indiana Avenue. Barrett, a longtime community leader and activist, had allegedly stolen more than two million dollars from 1,477 of his congregants in what proved to be an illegal fundraising operation. "I am appalled that from your pulpit you encouraged thousands of your church members-many of whom, according to your sermons, are oppressed economically, to invest $1,500 or more in your pyramid scheme," the judge told Barrett. By the end of the state’s investigation, Barrett would be shown to have set up three pyramid schemes in all, fleecing some 1,570 people and making large payouts to both himself and members of his family.

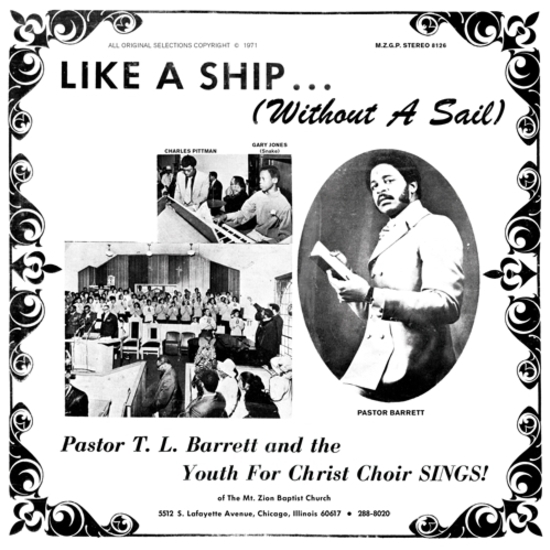

Nearly three decades later, Barrett’s legacy has little to do with these schemes. If you’ve heard of him, it is probably because some two decades prior to the scandal the then 27-year-old pastor brought his Youth for Christ Choir to the low-rent Sound Market Studio on Chicago’s Near North Side and recorded a gospel record. Here, the young minister, making his debut release, proved an inspired and versatile singer, and, despite their disappointment with having to record multiple takes, the 40 children of the Youth for Christ Choir delivered a string of stirring, almost eerie performances. With its impressive cast of session musicians, deep funk grooves, and chilling choral arrangement, the resulting album, Like A Ship (Without a Sail), would become a hidden classic. Over the course of the next 45 years, the album would be prized by collectors and revered by musicians including Jim James of My Morning Jacket, members of Radiohead, and Barrett’s fellow Chicagoan, Kanye West.

But the album’s legacy ignores its creator’s dubious afterlife, and the overlooked scandal invites a few questions: can a conman make a truly transcendent gospel LP? What do we make of something so beautiful created by someone who has done something despicable?

Thomas Lee Barrett came from a tradition of music and ministry. His father had been a part-time gospel performer who relocated his family from New York to Chicago in 1953 so he could help Barrett’s aunt begin her ministry at a new church. After his father’s death in 1960, Barrett drove back to New York, where he would arrive unannounced to stay the home of his uncle.

"We buried [my father] on October 24, 1960," Barrett tells Peter Margasak in the liner notes of the Like a Ship‘s 2010 Light In The Attic rerelease, "and I left Chicago that night and drove back to New York in search of the real me, and first of all, in search of the real God. I found God, but I didn’t find him up in the sky-I found that God wasn’t a Him, either God is, whatever, all energy, all power."

He took an odd job helping perform autopsies at the Flushing hospital, and by night he played piano at the Waldorf Astoria and the famous Manhattan nightclub the Village Gate. Feeling called to the ministry, Barrett left New York in 1966 and moved back to Chicago, where he he began his pastoral work at Mount Zion Church.

Barrett proved a charismatic and rousing minister with a passion for social justice. His take on ‘New Thought’ spirituality – a religious school of thought born in the mid-nineteenth century that teaches the ubiquitous presence of God – attracted a number of significant musicians to Mount Zion. In his congregation could be found future members of Earth, Wind And Fire Maurice White and Philip Bailey, Chicago soul legend Donny Hathaway, and frequent Sun Ra collaborator Phil Cohran.

The origins of Like A Ship reflects Barrett’s extensive network of friends and congregants, as well as his commitment to activism. The Youth For Christ Choir itself was developed as an after-school program for the children of the Mount Zion congregation, and it was through Barrett’s involvement with Jesse Jackson’s Operation Breadbasket (an organization dedicated to economic development in black communities) that Barrett met Ben Branch, the leader of Operation Breadbasket’s house orchestra. The Youth For Christ Choir would become a regular feature of Operation Breadbasket events, which is how Barrett met Gene Barge, a session saxophonist and arranger for Chess Records. It was Barge who would help facilitate the production of Like A Ship, boosting the church band with seasoned guitarist Phil Upchurch and session bassist Richard Evans.

The album was produced and recorded amid something of a popular revival in American gospel music. In 1969, Edwin Hawkins scored a sleeper hit with ‘Oh Happy Day’, a nineteenth-century traditional transplanted onto a steady soul arrangement. Within a year of the release of Like A Ship, Aretha Franklin would record her live gospel album Amazing Grace – to date the best-selling record of her rich career and best selling live gospel album of all time. That same year, Allen Toussaint would try his hand at gospel with his Life, Love And Faith, a gem packed with the neonatal kick of early funk. Even Elvis would cash in, with his 1971 compilation You’ll Never Walk Alone. While gospel artists had sold millions of records throughout the 50s and 60s, singers like Mahalia Jackson had refused any attempt at crossover success, denouncing (as Jackson did) the nefarious lure of the secular world. Gospel had surely exerted its influence over popular music in the early 60s, but gospel artists had largely resisted significant influence from the other direction. Now, by the late 60s and early 70s, even artists that had made their names in gospel – the Staple Singers chief among them-would come to embrace the irresistible rhythms and hooks of R&B, pop and (what would become) funk as they continued their evangelical projects. Seeing opportunity in this sudden surge in popularity, pastors like Barrett began to independently produce their own recordings. The result is a trove of regional gospel music documenting the convergence of diverse musical genres and theological ideas.

Barrett’s title track, ‘Like A Ship’, is perhaps his most ambitious reach for the crossover appeal of ‘Oh Happy Day’. Its infectious bass and piano groove carries you right through the forceful riffing of Barrett’s call and the eruptions of the Youth for Christ Choir’s response.

"’Like a Ship’," Barrett says, "that was me when I was 16. If you listen to the song, it says, ‘I know we can make it/I know we can take it,’ and whatever’s negative that’s clinging to us, ‘I know we can shake it.’"

I first heard ‘Like A Ship’ while sitting in front of my laptop in my parents’ living room, following a Spotify rabbit hole from the Lijadu Sisters to The Funkees. I was living with my parents, waiting tables at a taco restaurant and preparing to attend divinity school in the fall-not to be a pastor, but to study the medieval Christian mystics. I spent much of this time boning up on religious scholarship (including a passage in William James’ The Varieties Of Religious Experience that describes the New Thought tradition adopted by Barrett) and poking around the internet for new music.

When the organ intro to ‘Like A Ship’ began, I thought the song was a sleek funk instrumental à la Curtis Mayfield. Then Barrett and the choir began singing and something opened up. The song is at once joyful and despairing: sung in separation from the Divine and union with it.

For days I evangelised the song, playing it for my girlfriend, my parents, my sister… whoever would listen.

Pastor Barrett, Bill Russell, Isaac Hayes and the Reverend Jesse Jackson

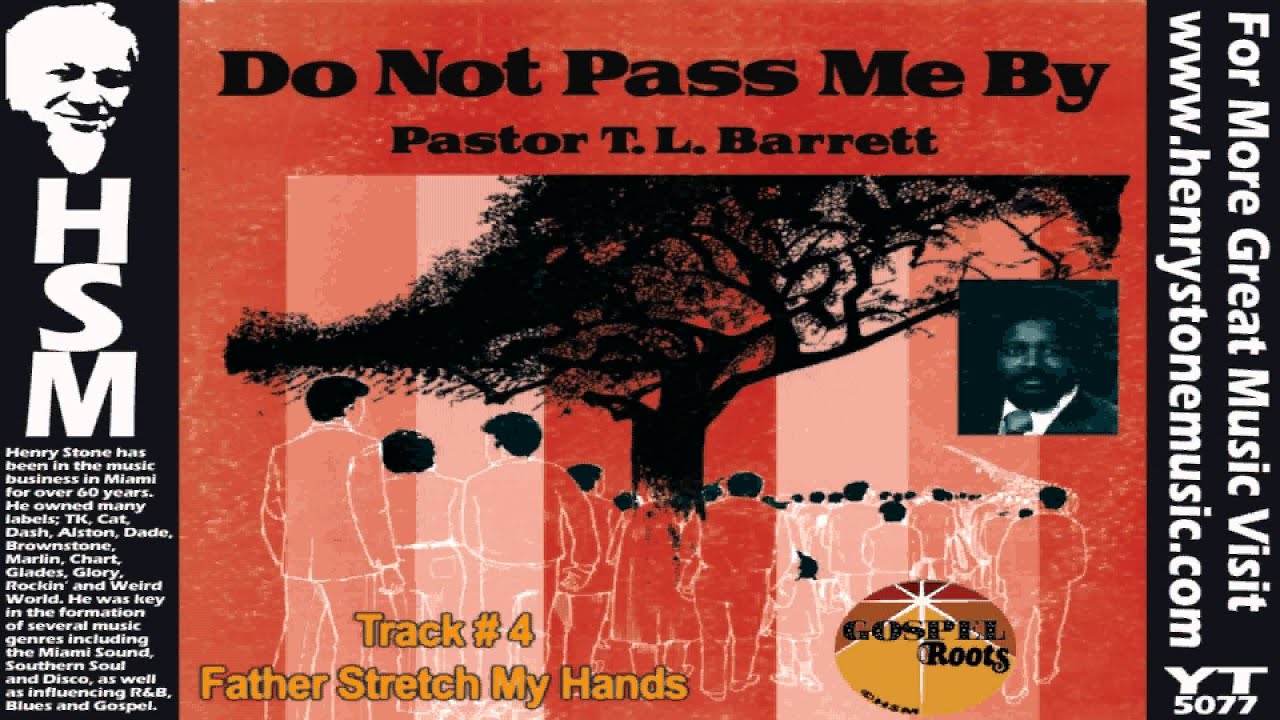

Like A Ship (Without A Sail) did not achieve the success of the other great gospel crossover records of its time. After self-releasing the album in 1971, Barrett continued his career as a pastor, selling the record at speaking events alongside recordings of his sermons. He’d record just a few other albums, notably the existential Do Not Pass Me By, made for a Henry Stone imprint in 1976.

In 1988, Cook County State’s Attorney Richard M. Daley began an investigation of a pyramid scheme at Barrett’s Life Center Church, where he had relocated after a theological break with Mount Zion’s elders. Investigators discovered that 1,570 people had lost $2,257,000 in what Barrett described as a plan for economic development for his community. (Adjusted for inflation, this amounts to roughly 4.5 million USD in 2016.) Parishioners had been promised payoffs of $12,000 for initial investments of $1,500. Most would never see any return.

Barrett, 44 at the time of the controversy, initially denied his "investment opportunities" plan was a scam. "We have no criminal intent," he told the Chicago Sun-Times in July of 1988. "We’re not hurting anyone." Barrett claimed that members who received $12,000 payoffs were expected to invest the money back into the community for economic redevelopment and debt relief.

State investigation of the scandal revealed an absolute lack of feasibility for the plan described by Barrett. Judge Robert Sklodowski ordered the pastor to turn over title to properties held by the church to a state receiver "because of the admitted complicity of your board members in this diabolical scheme."

"Claims have been filed by blacks, whites, Hispanics, minors, senior citizens and handicapped individuals," the state receiver’s report eventually revealed. "There were high school students, college students, clerical people, sales people, professional people, [and] city, county, state and federal employees."

Barrett agreed to repay $1.2 million by 1998 or face incarceration.

He would nevertheless remain an influential figure in Chicago’s black community. In 1998, Illinois Congressman Bobby Rush passed a House resolution in his honour, citing Barrett’s work as "an outstanding motivational speaker and teacher." Rush continued: "He is the author of many publications on the science of better living and positive thinking. He has organised numerous programs in the Robert Taylor Homes public housing complex, including the Big Brother and Sister program and the Life Enrichment program."

The resolution was made the year Barrett’s final restitution payments were due. He would not receive jail time. He still practices his ministry in Chicago.

All written accounts of Barrett’s life should be treated with discretion. The liner notes to the 2010 rerelease of Like A Ship reveal at least one incorrect date (claiming he was expelled from high school in 1966, when he was, by the notes’ own reckoning, already twenty-two), as well as a number of ambiguities regarding Barrett’s leadership at Mount Zion. This is also true of Rush’s resolution, which claims that Barrett first organised Mount Zion Baptist Church (he did not), and also claims that Barrett’s move from Mount Zion to Life Center was not a break but instead a renaming (it was not).

It could be argued that there are only two sets of truly reliable documents in understanding Barrett’s complicated legacy: the Chicago Sun-Times‘ coverage of the scandal, which is exact in its appraisal of the scheme, and the albums, which are precise in another way.

The Youth For Christ Choir is certainly not the most traditionally beautiful gospel choir on record. You won’t find the slick polish of Kirk Franklin’s groups, or even the tightness of the Edwin Hawkins Singers. There is a rough, almost dissonant quality to the YCC’s singing (see ‘Nobody Knows’) that lends the songs desperation and urgency. It is this slight ugliness that makes ‘Like A Ship’ much more moving than the euphoric ‘Oh Happy Day’. Later in ‘Nobody Knows’, when Barrett sings his psalmic "I’ve been abused, and I’ve been scorned," it is the desperation in the choir behind him that brings his point home.

As someone interested in the history of religious thought, I’m fascinated by people who at set themselves apart in search of some kind of holiness. People like Barrett (or St. Francis of Assisi, or the desert fathers and mothers… pretty much anyone in the religious orders) who leave one kind of life in search of another. I am also necessarily very wary of anyone who assumes authority in spiritual matters.

So where does this leave Barrett? Does his "diabolical scheme" undermine Like A Ship‘s angelic beauty? Can the acts of a 44-year-old stain the work of the same man-the then-innocent man-at 27? Again, what do we make of someone who has made something great and who has also done something reprehensible? This is the question that has lately inspired the fierce debate surrounding the work of many ageing male artists, especially Bill Cosby, Roman Polanski, and, most recently, Nate Parker. (See also: Jimmy Page, R. Kelly, Phil Spector, Afrika Bambaataa, Gary Glitter…)

Of course these questions must be taken on a case-by-case basis. We must not let the beauty of a beloved work allow us to wilfully ignore the crimes of its creator, but once we have considered those crimes, each of us must carefully weigh out the ethical ramifications of our consumption. It might be a matter of elapsed time: Does my partaking of X enable its maker to continue his crimes? Or cover his tracks? It could be a matter of contemporaneity: Was he doing Y terrible thing while making his now-canonical jokes/film/album? Or it could be by degree. Or remorse. They are all interrelated factors, the severity of each enhancing or reducing the consequence of the other.

Some of these considerations certainly figure into my understanding and appreciation of Like A Ship. Whereas Bill Cosby and Roman Polanski have yet to atone for their crimes, Barrett has answered for his. Furthermore, these crimes are not interchangeable; it goes without saying that financial fraud is not serial rape. But, as any conflicted fan knows, it is a ultimately gut call, not an algorithm.

As for the album, it remains a document of joy, despair, and seeking, and I believe it stands as the finest gospel masterpiece of its era. Had Barrett’s record come after his scandal, it could be seen as a kind of redemption. And perhaps it is. Seattle’s Light In The Attic Records rereleased Like a Ship (Without a Sail) in 2010. Colin Greenwood of Radiohead describes it as "The most euphoric celebratory music that makes you want to jump around the house and explode with joy." Jim James of My Morning Jacket has called the record "[o]ne of the most important albums ever made. Ranks right up there with What’s Going On, Dark Side Of The Moon, and Pet Sounds as a flawlessly executed vision brought to life in perfect harmony. Enriches the soul and expands the mind."

The Talmud lists redemption (teshuvah) among the things that predate the creation of the universe. In this way, redemption exists beyond time, and it is there, waiting for us should we reach out for it. We are, for the most part, pretty good at understanding chronological redemption. Paul holds the coats and then he falls off his horse. Augustine has his orgies and then he sees the light. But the question stands: can something good from our past redeem us when we fail in the future?

I think it can, in some cases. Sometimes our holiness transcends us. Sometimes our holiness transcends us because we are imperfect. In fact, it always does.

In the last year, Chance The Rapper and Kanye West (both also from Chicago) have released self-styled "gospel" recordings that reference Barrett’s music and the tradition in which it fits. Chance The Rapper’s Coloring Book – with its heavy use of choir and choir samples-certainly reaches the transcendent gospel heights of Barrett’s masterpiece. The mixtape’s opener, ‘All We Got’, ends with the appearance of the Chicago Children’s Choir, a group (like Barrett’s Youth For Christ Choir) founded to bring music education to under-served Chicago children. And like Barrett, Chance deftly blends genres. ‘Blessings’ is a gospel number filtered through hip hop; ‘Same Drugs’ is hip hop refracted through gospel. Shaman Shafii of the Michigan Daily goes so far as to use Like A Ship to frame his review of Coloring Book, describing the mixtape as "what it would have looked like if Barrett had Internet access in 1971." But Chance (unlike Barrett) is forthcoming with his vices, and Coloring Book is as much a slacker’s lament of alienation and longing as it is a praise-and-worship record.

Kanye has always rooted through the gospel bins for samples, but The Life Of Pablo cites Barrett directly. The album’s second track, ‘Father Stretch My Hands, Pt.1’, borrows its title from Barrett’s 1976 recording of the same name. (This is also the track with what I believe to be the album’s most regrettable lyric: "Now if I fuck this model/ And she just bleached her asshole/ And I get bleach on my T-shirt/ I’mma feel like an asshole.") Kanye begins ‘Father Stretch My Hands, Pt.1’ with a sample of Barrett’s song:

"You’re the only power (power)

You’re the only power that can

You’re the only power (power)

You’re the only power that can

Father."

Perhaps no one is better suited to reference Barrett more than Kanye, a supremely talented Chicagoan, an artist always navigating a balance between redemption and his own ego, capitalising on God while still loving and fearing Him.

Kanye continues:

"Just want to feel liberated, I, I, I

I just want to feel liberated, I, I, I

If I ever instigated I’m sorry

Tell me who in here can relate?"

Barrett could.