On 5th August 1976, Eric Clapton took to the stage at the Birmingham Odeon. This strange brew of a man was hitherto known as a slightly self-effacing virtuoso who liked a quiet life and had done his best to keep the peace while in Cream between the ever-warring Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker. He was seen as a musician whose heroes included Muddy Waters and Robert Johnson; as someone who idolised Jimi Hendrix even as he tried to rival him in the late 1960s; as a brilliant guitarist who had rejected the noisy histrionics of rock God-dom in the 1970s in favour of a mellower, more reflective style. Tonight, however, somewhat the worse for wear, he had something on his mind. Something ugly and toxic.

"I used to be into dope, now I’m into racism," he slurred. "It’s much heavier, man. Fucking wogs, man. Fucking Saudis taking over London. Bastard wogs. Britain is becoming overcrowded and Enoch will stop it and send them all back. The black wogs and coons and Arabs and fucking Jamaicans don’t belong here, we don’t want them here. This is England, this is a white country, we don’t want any black wogs and coons living here… Enoch for Prime Minister! Throw the wogs out! Keep Britain white!"

He later attempted to pass the rant off as a "joke", yet never apologised for it, repeatedly, soberly extolling the virtues of Enoch Powell, who had warned of the dangers of immigration in 1968 with his infamous "Rivers Of Blood" speech.

Clapton wasn’t the only rock star of a twisted, right wing bent in the 1970s. David Bowie’s comments about the need for Britain to experience a disciplinary dose of fascism, coupled with his supposed Nazi salute delivered at Victoria station were greeted with horror but in fairness he managed to live the infamy down over the years through repeated acts of contrition, his outburst not forgotten but forgiven. Less publicised and more commonplace were the reported attitudes of Roger Daltrey (who recently spoke out against "mass immigration" and declared his intention to vote for Brexit) and Rod Stewart, who displaced The Sex Pistols’ ‘God Save The Queen’ at number one in 1977 with ‘I Don’t Want To Talk About It’. What he had been happy to talk about was his own enthusiasm for Enoch Powell, who he described as "the man".

Rock Against Racism was formed in 1976 off the back of an open letter written to the music press by Red Saunders and Roger Huddle in response to Clapton’s outburst. Describing him as "rock’s biggest colonist", they argued for a rank and file movement that opposed the "racist poison" of the likes of Clapton, as well as that disseminated by the growing threat of the National Front. RaR succeeded in politicizing punk and dispelling its early bad habit of sporting the Swastika.

The groups that came after the initial punk wave began to reflect the increasing diversity of Britain’s streets. Come the 1980s this was evident not just in The Clash and PiL’s avowed love of reggae or the mordant take on funk as an alternative, serrated weapon as practised by Gang of Four, The Pop Group and A Certain Ratio. It was also seen in the healthy racial mix of groups like The Beat, The Specials, UB40, The Selecter, all of whom had pop hits and a public profile. They represented an extremely potent, practical example of the slogan Black And White Unite To Fight, just when it was most sorely needed. It was no coincidence that Madness, despite their adoption of ska, attracted such a strong National Front contingent – they contained no black members. The spectacle of racial integration was vital, and in their case, vitally lacking.

The wave of punk-derived New and Electro-pop, from ABC to Depeche Mode to New Order, scotched lumpen assumptions that it stood in opposition to disco, representing some roar of Caucasian street authenticity. The best new early 80s music was alive to other cultures in a way that white 70s rock, with its grandly conceptual, gatefold, virtuoso pretensions and implicit disdain for more earthy styles, as well as its head-up-arse, unreconstructed political attitudes had not been.

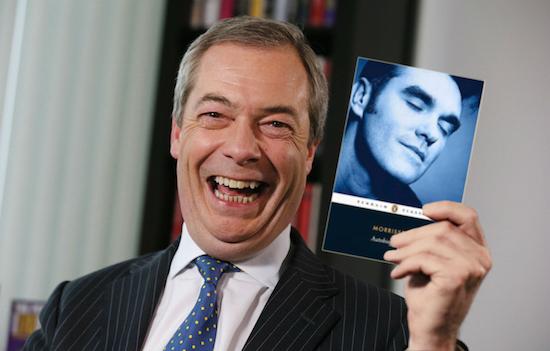

Cut to 2016. Against a background of post-Brexit tensions Morrissey has yet again invited contempt for his serial views regarding race and ethnicity. Last week, he said that London’s first Muslim mayor Sadiq Khan "eats Halal butchered beings and talks so quickly that people don’t understand him… and that suits the British media perfectly." Pop’s own Prince Phillip is no stranger to such remarks, in the past speculating on whether the Chinese are a "sub-species" and complaining that "the gates are flooded and anybody can have access to England and join in.". All of these are given as signs of the degeneration of a once-radical figure, but right from the outset, Morrissey and The Smiths represented a fatally reactionary moment in British pop culture – a severing of punk and post-punk’s honourable links with black musics. They were here to reject colour in every respect, be it the gaudy, neon-lit backdrop of Top Of The Pops against which Morrissey wanly cavorted, or the colourisation of indie afforded by its embrace of dance music and reggae. Their wistful cover artwork, harking back to popular icons of the 50s and early 60s, were redolent of a time when black people had a near-zero cultural imprint on the British consciousness, unless you counted the hugely, inexplicably popular The Black And White Minstrel Show. This was explicit, as well as implicit. Morrissey spoke of a conspiracy to promote black music in the British charts, while opining that reggae was "vile".

As a solo artist, meanwhile, Morrissey bitterly disappointed the large number of Asian fans he may never have known he had. Some young British Asians, misfits in conservative homes and in society at large, found in Morrissey what they thought was a kindred spirit. And what did he lay on them? ‘Bengali In Platforms’, on the 1988 album Viva Hate.

After The Smiths, indie was never quite the same; it became whiter, samier, more conservative, eventually culminating in the retro-consensus of Britpop. Working in the weekly and monthly music press we were regularly informed by the marketing department, backed up with stats, that to put a black act on the front cover of an edition would result in a fall in sales. We knew that but we did it anyway; after all, you couldn’t put The Cure on the cover every week. Judging by the spread of music press covers I surveyed researching an upcoming book about the year 1996, it seems those voices from marketing, an increasingly influential department as music press publishing entered a slow decline, were being heeded. Black music activity was referenced, but marginalised, despite the success of drum & bass, trip hop and garage. When faced with criticism that they weren’t featuring enough acts of colour on their covers, editors found themselves resorting defensively to the drummer of Ocean Colour Scene. White music became very normative in the overall spectacle of things. But did that matter? After all, entering the 21st century, we were well on our way to a post-racist society, surely, the ignorance of yesteryear had long since been banished.

Unfortunately, there has subsequently been a contradictory drift as with the assertiveness of multiculturalism came a new separatism. Cut again to 2016 and it turns out that, far from Britain having resolved its issues with race, many people simply kept their thoughts to themselves, aware that such thoughts were taboo but unable to banish what their "gut instincts" (or, alternatively, ancient prejudices) told them about modern society, so white and so happy not so long ago. They expressed themselves guardedly and codedly with terms like "banter", "legitimate concerns". Then, after the Brexit vote, which some imagined was to decide whether or not immigrants should leave the UK, not the UK leave the EU, they were emboldened again. Kick out the Poles, the new "wogs". There, we said it. And while we’re at it, kick out the old wogs. Reports of racist incidents have leapt since the Brexit vote.

There’s a decreasing mood for radical Asian musical voices like Asian Dub Foundation in an age when even supposed liberals eye Muslims with barely concealed antipathy, suspect them of harbouring Islamofascism in their ranks. Gentrification, meanwhile, as exerted its own ethnic cleansing. The Arches in Brixton are due for demolition. Over recent years, clubs and venues catering for black music in areas such as Woolwich have found themselves closed down, not necessarily for economic reasons. There was widespread alarm at the recent water fight in Hyde Park, which got out of hand and resulted in the stabbing of a police officer. Papers like the Evening Standard were loath to return to the infamy of 1980s Daily Mail headlines like BLACKS GO TO WAR ON POLICE but – well, look at the pictures. And some of them were shouting "Black Lives Matter". Do we need to spell it out?

What the Hyde Park incident may have reflected, however, was the increasing de-legitimisation of Black/British club culture, which, it is assumed, will bring with it problems of drugs, violence, gangs, shootings. The police even have their own risk assessment procedure, Form 696, which has led to the widespread prohibition of grime events, including the Just Jam event scheduled to take place at the Barbican in February 2014 but cancelled at the last minute following mysterious "police advice". Grime, perhaps the only innovative UK genre of the 21st century, is effectively subject to prohibition on account of the dangers young black people are supposed to represent. Repress it, however, try to sweep it under the carpet, and predictions of lawlessness become self-fulfilling. One of the sadder aspects of contemporary techno, a music originated by African-American 80s pioneers like Derrick May and Jeff Mills, is the near-100% whiteness of its audiences today. Is it cynical to suggest that that is a condition of its success?

With racism clearly far from extinguished, is it time for the initiative of Rock Against Racism to be revived? A simple reiteration of that movement probably isn’t the answer – you might as well call for a "new punk". No one, certainly not Morrissey, is quite as obnoxiously overt as 1976 Clapton any more, we can at least say that much, though Phil Anselmo of Pantera certainly tried to give it a go with his white suprematist larks at a California gig back in January. Subconscious racism, manifested in sins of omission abounds, of course, but those responsible will protest that they Don’t Have A Racist Bone In Their Body. But this absolute denial, this spurious claim of utter cleanliness by allows racism to flourish insidiously like an unchecked, interior disease whose manifestations are only evident at a much later stage. Recently, The Sun protested at an overdue trainee scheme by the BBC actively to recruit more black and ethnic minorities. The rag, which has a long and honourable history of complaining about racism against white people dating back to the 1980s, claimed that the scheme was "anti-white". But the Corporation’s failure to reflect the wider composition of the UK population is palpable, and replicated across the entertainment industry, though economics has its role in this too – only Old Money and its attendant skin hue gets to take up the unpaid internships that are the only route into a career in the media, or has the connections and wherewithal necessary to start up a career in acting. Racism today is part of a wider class issue.

Much of this is because rock and pop have lost their cultural centrality and a focal place to disseminate themselves, with old institutions like Top Of The Pops and the weekly music press having collapsed. There’s arguably far less movement between underground and mainstream, meaning marginal voices of all backgrounds are less likely to reach a wide audience. Given just how fertile our music currently is, this is frustrating. Without an ability to use pop as a Trojan horse to reach millions of homes from all walks of life, new political movements might now regard pop music as less relevant to their tactics.

2016, however, could be a chance for leftfield musics to find new ways to reassert their relevance in mainstream discourse. Although grime is making tentative inroads into America following the patronage of Kanye West, there’s clearly far more to be done. What might be required is an active, conscious celebration of the musics of other cultures, North African and East European Asian and African-American as well as UK homegrown, which give the lie to assumptions of default white hegemony. Don’t just leave it to the market to decide, don’t assume we’ve come anything like as far as we think we have. We need to take up old cudgels. There are things happening, in clubs and bedrooms and workshops, booming and bristling on the peripheries, scratching at the doors. These things happening – or yet to happen through lack of encouragement need to be sought out, pushed forward, actively celebrated and espoused in the context of the UK right now. Brexit isolation is neither inevitable politically nor culturally. Kick against the gentrifiers and whitewashers and the halfway-out-of-the-closet- racists. Rage against the realists. Invade the bigger picture. Bring back the melting pot.