A massive fan of massive bands, the radio disc jockey Zane Lowe once tried to draw a parallel between three of his favourite big hitters: Pearl Jam, Radiohead and Kings Of Leon. Interviewing the second upon the release of In Rainbows, Lowe compared the Oxford group to their apparent American counterparts on the grounds that they "do exactly what they wanna do and they continue to make great records and they have the back catalogue to back it up." To this Ed O’Brien replied, "I saw Pearl Jam last year and it blew my mind." Then they span ‘My Party’ by Kings of Leon, who are so patently not in the same league as the other two that it’s like making good use of a WH Smiths 3for2 offer by purchasing Jude The Obscure, East Of Eden and The Formulaic Romance That Could Be Easily Be Adapted Into A Screenplay by Nicholas Sparks. I wouldn’t piss on them if they or their sex were on fire.

O’Brien’s disclosure that he’d recently seen Pearl Jam perform for the first time in his life wasn’t the most revealing remark of all time but the similarities between his band and the Seattle grunge merchants are worth exploring further. As Lowe implied, they each move in a similar league, maintaining both huge popularity without pandering to the populist by-numbers naffness of U2 whose own creative urges have been permanently fulfilled by dressing up as The Village People and shouting the word "discotheque" in front of a large shiny lemon. Both Pearl Jam and Radiohead, and particularly their singers, could be accused of maintaining a certain arrested adolescent mopishness. Both have written a song called ‘Present Tense’. Both have an Ed in the band and two As in their name, and you might think they’re stylistically disparate but play Radiohead’s ‘Bodysnatchers’ back-to-back with Pearl Jam’s ‘Do The Evolution’ and you might have to reconsider.

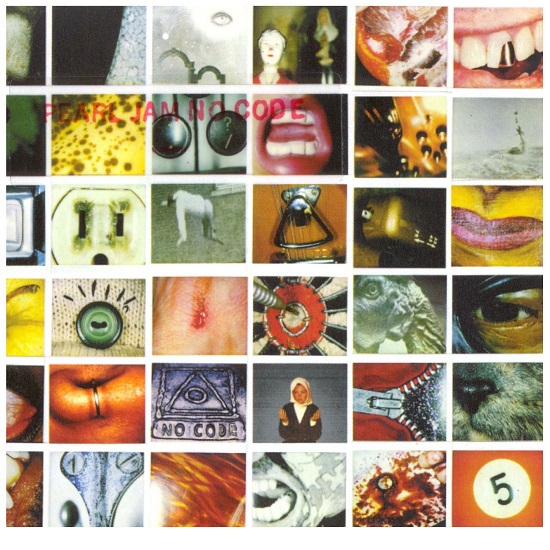

And if Pearl Jam had their very own Kid A moment then it was in 1996 with the release of No Code.

Now I don’t know about you but when I was at school virtually every one of my friends had their own different favourite Pearl Jam album. A great number of lunchtime arguments were waged over this lack of consensus, alternatively resulting in belly-laughter, tears, physical fights or a competition to see who could do the best Eddie Vedder impression. The latter involved swinging from the rafters of our unsupervised form room like Mr Vedder did in the ‘Alive’ video while whoa-whoa-ing as deeply as our only partially broken voices could muster and all these years later I realise that was the happiest I have ever been. When asked by his loving family how he’d ideally like to die, one of the immobile real-life Jim Royle Dads on Channel 4’s Gogglebox replied that he would preferably wish to expire during the act of playing football in the park, using jumpers for goalposts, with all his old schoolmates. Then he started weeping. It seems as good a way to go as any, though I was never a fervent fan of footy so when I receive the inevitable inoperable diagnosis after a lifetime of consuming battered processed sausage instead of the existence-prolonging cuisine that is fish, all I’ll need to do is hire a classroom with the appropriate ceiling beams, relearn the words to ‘Even Flow’ and ensure that I land in a fatal enough position when my arms give way. That’s got to beat the solemnity of Dignitas. I’ll invite you via the Facebook group.

Anyway, one of my schoolmates was a loyal advocate of Ten, insisting that Pearl Jam had never bettered their raucous debut. Personally I preferred its follow-up, Vs., which I felt had a greater miscellany of flavours and textures and a far better front cover (a cheesy group high five is no competition for a close-up photograph of an irate sheep). Somebody else plumped for Vitalogy which had indisputably excellent packaging (even its cassette pressing was to die for) and included some of Pearl Jam’s best songs, particularly the two ballads with ‘man’ in the title. Vitalogy was even more diverse than Vs, although most of its experimentation had been channelled into silly, throwaway moments such as ‘Pry, To’ and ‘Hey Foxymophandlemama, That’s Me’. Another of my pals even had the gall to claim that Yield was the best Pearl Jam album which was complete and utter madness given that most of its songs were as forgettable as a consummate spy’s face.

As time cruelly wrenched me further and further away from that young boy I once was, so full of hope, spunk and battered sausage, as my tastes broadened and ripened and I began trying out seafood and purchasing cod liver tablets to stave off the Reaper, my loyalties transferred from Vs. to the more mature sound of No Code. Reminiscent of Bruce Springsteen or Neil Young’s moments of splendid contrariness, it is the least bombastic Pearl Jam album, the one that is trying the least hard to be liked. In certain aspects it is actively trying to be disliked, an attitude it shares with Kid A. Pearl Jam may not have dabbled in Aphex Twin-inspired ambient IDM but No Code still has a lot of weird, awkward, downbeat material on it and that’s what makes it so rewarding.

Pitchfork’s 5.4 out of 10 review of No Code complained that "there’s a ton of filler here. In fact, it’s almost all filler." But can a record be all filler? If a record can be legitimately described as all filler, doesn’t that suggest that there’s something else going on, something more deliberate and premeditated than the mere padding-out process that the term "filler" implies? I’m reminded of when some individuals complained that Kid A "didn’t have any songs on it."

You can tell something’s not right from No Code‘s outset. Whereas Pearl Jam’s previous albums had all opened boldly with little-nonsense balls-out rock numbers, this one eases itself in with the quiet lullaby that is ‘Sometimes’. ‘Who You Are’ was also a decidedly self-defeating choice for its lead single, commercially speaking. Based around a polyrhythmic drum pattern inspired by the bebop pioneer Max Roach and with Eddie Vedder playing electric sitar and muttering spiritualisms about "transcendental consequence" and "trampled moss on your souls", as a purposefully alienating method of paring back a fanbase it’s up there with Thom Yorke repeatedly declaring how he woke up sucking a lemon.

Unsurprisingly, this was not a happy time in the Pearl Jam camp. They’d been embroiled in and distracted by their much-publicised, often mocked and ultimately futile anti-Ticketmaster campaign. Bassist Jeff Ament didn’t even find out the band were recording No Code until three days into the session and nearly quit as a result. Among the many other problems he had with becoming a VIP, Eddie Vedder had been pursued by a mentally imbalanced stalker which was the reason he’d contributed so little to his band’s 1995 collaborative album with Neil Young. "Leaving the house wasn’t the easiest thing to do," he explained. When Pearl Jam received a Grammy Award in early 1996, Vedder’s speech had been characteristically uneasy. "I don’t know what this means," he announced, "I don’t think it means anything. That’s just how I feel." Because he’d still bothered to turn up though, this did come across as a rather "absurd, self-conscious and silly" attempt at "tryin’ to be cool", as the bassist of The Presidents Of The United States Of America observed.

As Radiohead would experience later, by 1996 the pressures of success and mammoth touring schedules had left Pearl Jam burned out and wanting to sound like a completely different band. Amidst this identity crisis was their paradoxical desire to retreat from the limelight while still creating and releasing music. Kid A may have been a divisive record but it still proved a critical and commercial success, so Radiohead ultimately fumbled their efforts to repel. Pearl Jam, on the other hand, were more successful in pursuing unsuccessfulness, at least in the short term. No Code was the first Pearl Jam album to fail to soar to multi-platinum status and Vedder would later reflect that "even our fans didn’t know that No Code was out at the time. I talked to people who love our music and they weren’t aware it existed."

By the end of the 1990s, Thom Yorke had become as sick of the sound of his own voice as the rest of us had and thus felt the urge to disguise it by pretending he was a robot, albeit a robot with feelings whose virtual emotion dial was set permanently to "sad". Again, Vedder’s actions hadn’t been as radical as that, though throughout No Code he does sound like he’s trying to escape the past and reinvent his singing style. Vedder croaks, mumbles, whispers, slurs, screams, talks, wails, yelps, threatens to yodel at one point and clicks his tongue as if trying to spit out a couple of chirping crickets. He even allows guitarist Stone Gossard sing the lead on one track. There’s barely a "whoa-whoa" in sight.

The record is musically adventurous too and, unlike Vitalogy, its experimentation is incorporated into fuller bodied songs. There are further delicate lullabies in the form of ‘Off He Goes’, a six-minute fireside ballad in which Vedder accuses himself of being a terrible friend, and the even prettier final track ‘Around The Bend’. The latter was written by Vedder for drummer Jack Irons to sing to his young son as he drifted off to sleep, although the singer has also offered the darker interpretation that they could be the words of a cannibalistic serial killer serenading his victim. A sister track to the single, ‘In My Tree’ showcases more of Irons’ intricately tribal drumwork, clouded in hazily psychedelic guitar work. It fades out too early I think, as does the even trippier spoken-word track ‘I’m Open’. Even the heavier moments are atypical of Pearl Jam’s signature hard rock style. There’s something intriguingly weary and lumbering about No Code‘s first loud number ‘Hail, Hail’. Then there are ‘Lukin’ and ‘Habit’, both raw and spontaneous, the first is a minute-long blast of clattering punk rock, whereas ‘Habit’ is a furious anti-drugs rant that verges on heavy metal. The bluesy, Crazy Horse-ish ‘Smile’, meanwhile, is one of the album’s poppier pieces, although even this one borrowed its lyrics from cult Milwaukee weirdoes The Frogs.

Gossard’s lead vocals occur on ‘Mankind’, a scathing attack on second-wave grunge imitators which is played in a bouncy, catchy new wave style. "What’s got the whole world faking?" Gossard asks and if you look at the broader picture you could argue that No Code is not only Pearl Jam’s Kid A moment, it’s pretty much grunge’s Kid A moment to boot. It’s a misconception that grunge died at the very moment that Kurt Cobain tragically topped himself. That symbolic gesture provided a tidy would-be bookend to the movement but the reality was less neat and longer term and Nirvana’s attempt at culling their own popularity, 1993’s In Utero, was hardly grunge’s swansong. Hole’s masterpiece, Live Through This, was released shortly after Cobain’s death and Courtney Love’s band remained active until the end of the decade. Even if they never achieved festival-headlining world domination, the act that many in the Seattle scene accepted as grunge’s greatest band, Mudhoney, continued their career uninterrupted and are still going strong today. Soundgarden and Alice In Chains, both of whom recently reformed, released their "final" albums in the same year as No Code, in the form of Down On The Upside and Unplugged. Screaming Trees’ last effort also came out in 1996, as did Pentastar: In The Style Of Demons by Earth (not strictly a grunge band, though they were led by the Seattleite best friend of Mark Lanegan and Kurt Cobain, Dylan Carlson) which was followed by a lengthy hiatus.

At the same time, 1996 saw the grunge nostalgia industry kick in with the release of the Hype! documentary and Nirvana’s posthumous From The Muddy Banks Of The Wishka live album. It also saw an acceleration in the rise of the post-grunge scene lamented by Gossard in ‘Mankind’. Nickelback, Matchbox Twenty and Semisonic all released debuts in 1996. Puddle Of Mudd and Creed were working on theirs. 3 Doors Down and Lifehouse formed. But it wasn’t all bad. Because, while those groups were jumping on the bandwagon, Pearl Jam were toppling off it in style. Radiohead would do a similar thing with their own "difficult fourth album" as they found themselves surrounded by glib pretenders: Coldplay, Muse, Snow Patrol and all those fragile American emo bands with a penchant for British indie that the skinny kid from The O.C. would put on his headphones after falling out with a girl that he liked.

Pearl Jam would refrain from releasing anything as strange and innovative as No Code ever again, just as Radiohead would draw back from the radicalism on their post-Kid A records by reintroducing indie guitar sounds and writing those easily comprehensible things some people refer to as "songs". Though neither would brave anything that far-out again (to date, at least) and the quality of subsequent releases would certainly waver, both groups proved that they would always have more to offer, more to draw upon, than your average superficial guitar-based group. Both were transitional records, black sheep of each band’s catalogue, that they had to make in order to move forward. They were troubled masterpieces, therapeutic in nature, and each outfit came out the other side with a greater sense of who they were and who they wanted to be, leaving the competition floundering in an entirely different lane of the artistic swimming pool. And one thing’s for sure, neither No Code or Kid A could ever have been conceived by Kings Of chuffing Leon.