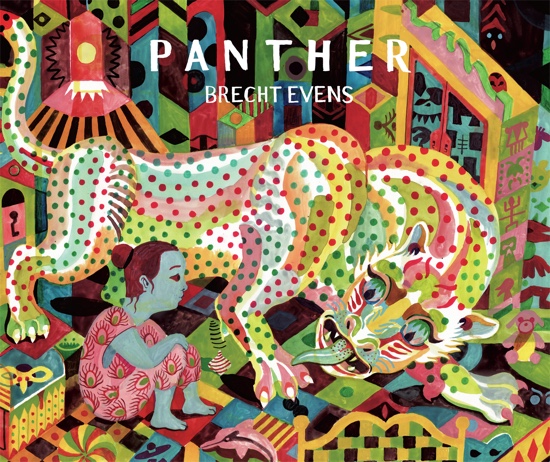

This month we have a lot of reviews to fit in. We have a new writer joining the team, Matthew Laiosa, who reviews Peplum and Panther. Brecht Evens’ Panther is undeniably one of the standout releases so far this year, blending astonishing watercolour art and an increasingly menacing tone. The variety with which he depicts Panther and later his friends is a wonder to behold. There’s an image towards the end that I cannot get out of my head, a sideways glance at the reader from Bonzo that confirms what we already know by that point, that bad things are soon to happen. It’s reviewed below.

Next month sees the 5th East London Comics & Arts Festival, which looks to be an excellent event spread over three days (10th-12th June). The list of exhibitors and events is huge, and this year is the launch of the ELCAF award to fund the development of an artistic project. More info and tickets are available from the ELCAF website.

Various – Dirty Rotten Comics #7

(Throwaway Press)

Let’s get this out of the way: you should buy Dirty Rotten Comics #7. It represents shockingly good value at a mere £4 for over 60 pages, and there is some absolutely brilliant, and very funny work here. Comedic talent is not restricted to the artists – the foreword assures us how politically correct they are, and that they have applied for recognition from the World Esperanto Association. Turn the page, and Matthew Dooley’s opening strip features a swearing butterfly with a swastika on its wings. This is followed by a few pages from Alexander Potts, an artist I’d really like to see more of. There are a lot of names that are new to me, and the overall standard is very high. Mhairi Braden’s Night Shift is a powerful piece, presumably autobiographical, about working on a hotel reception desk. It’s preceded by Aged Eleven, Kirk Campbell’s single page strip where a schoolboy introduces himself to his new teacher. Both are excellent, could hardly be more varied tonally or stylistically, and illustrate exactly why this book works so well. There are so many pieces here that most are very short, and nothing outstays its welcome. When you’ve so little space, you’ve got to get to the point fast. Or not at all, in some cases, but that’s fine. There’s a constant shifting through artwork, length, style, tone, in fact everything but quality. Funny, varied, intermittently dark and great value, this is a brilliant anthology. Pete Redrup

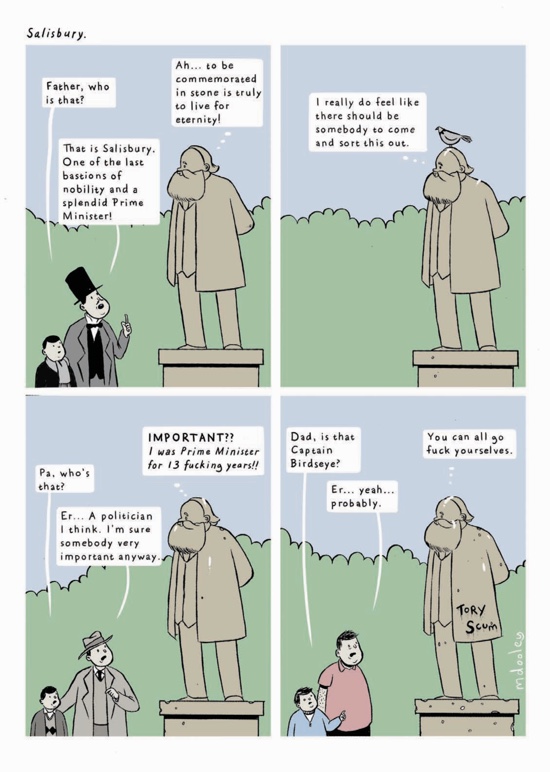

Matthew Dooley – Meanderings

(Throwaway Press)

Throwaway Press has also just released Meanderings, Matthew Dooley’s first collection, including several pieces featured in earlier issues of Dirty Rotten Comics, Off Life and more. It’s full of short, sweary, funny strips showcasing his deadpan humour and particular aptitude for punchlines. There’s some highly original work here – highlights are one with two sculptures discussing how they feel about where their respective destinations once sold, Salisbury, about a statue of the former Prime Minister, and one of blue plaques commemorating different stages of Dooley’s life.

Meanderings is a very well put together comic, crisply printed on glossy paper with lovely thick covers, and is certainly worth picking up. Pete Redrup

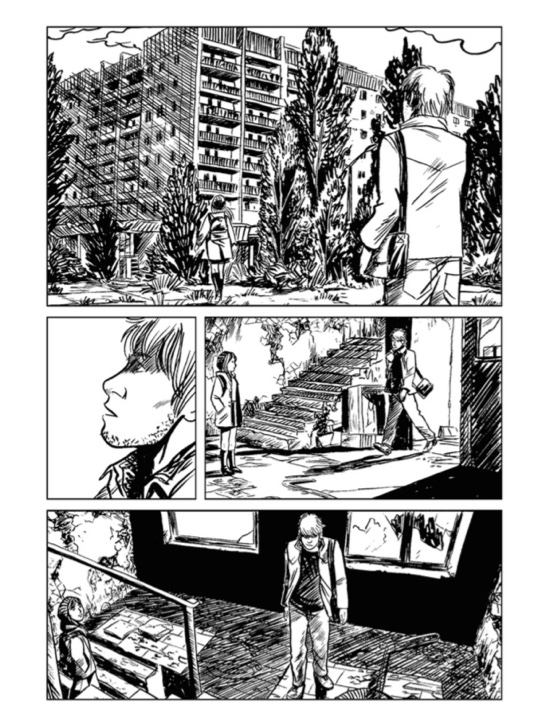

Natasha Bustos & Francisco Sánchez – Chernobyl. The Zone

(Centrala)

Presumably reissued to coincide with the 30th anniversary of the Chernobyl disaster, Natasha Bustos and Francisco Sánchez’s Chernobyl. The Zone is a fictional account of one family’s experiences. The book starts slowly with Leonid and Galia, an elderly couple returning to live in their farm in the nearby countryside some time after the accident. We watch them quietly pick their lives back up in a series of wordless wide-panelled pages, until they finally speak some 20 pages in. There’s a gentle cinematic quality to these images, a counterpoint to the scenes of decay. When Galia falls ill, her husband walks to nearby ghost town Pripyat in search of medicine, whereby the story rolls back to 1986 as the generations go forward to Vladimir and Anna. Vladimir works at the power plant; Anna (daughter of the couple we first meet) is pregnant. This section depicts life in the town built for workers at the power plant before the accident, the disaster itself and then their evacuation three days after it happens. In the final section, set in the present day, Anna’s children return to Pripyat to make an illegal visit.

Whilst we’re all familiar with what happened in Chernobyl, the human cost is not always emphasised. Over half a million ‘liquidators’ worked to clean up the accident, most [check] of whom died. Pripyat residents were exposed to massive doses of radiation for three days before evacuation, and the human fall out of all of this is still being felt today. Chernobyl. The Zone’s restrained storytelling and sympathetic art combine to bring this home by focusing on just one family, far easier to empathise with than something on a larger scale. Pete Redrup

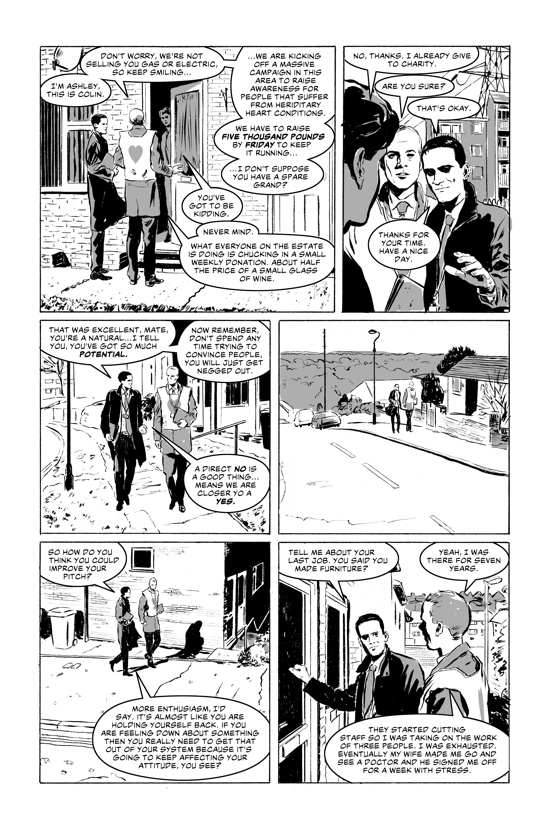

Will Volley – The Opportunity

(Myriad Editions)

The Opportunity is Will Volley’s debut graphic novel, inspired by his own experience of working in door-to-door sales. Colin leads a team trying to persuade people to sign up for charitable giving, and is on the verge of the promotion he’s been dreaming of when he finds the terms have changed and he has a week to hit new targets or lose out to his rival. There’s a huge focus on self-belief, not just for Colin himself but also for everyone in his team. He sports a permanent rictus grin as he insists they are all winners, and are all about to get rich with him. Of course, this outwardly positive philosophy conceals inner doubts, and we soon see this dichotomy goes much higher than Colin in an organisation that is basically a pyramid scheme.

Colin is also in serious debt to dangerous people, but dreams of earning enough to start to build a buy-to-let property empire so he can retire. This is a story of desperate people in modern Britain, well aware that for years the richest have been accruing wealth as the majority work harder whilst getting poorer. They believe success in this type of sales is their key to joining the elite and leaving behind the world in which the rest of us live, where jobs aren’t easy to find and it’s becoming harder and harder to earn enough to buy a house.

This gritty urban noir is rendered in a style well suited to the content, that somehow reminds of British work like early 2000AD despite being not particularly action orientated. One challenge a book like this faces is that it’s hard to empathise with any characters, so we don’t necessarily care what happens to them. If we’d seen Colin as he was sucked into this world we might be more sympathetic, but that would have been a very different work. Nonetheless, it’s an interesting and enjoyable tale contextualised by the short afterword, in which Volley writes about his own brief foray into this field, with reference to those ads we’ve all seen promising high wages for unspecified work, no experience required. We can all relate to hope even if we’ve never fallen for scams like these. This is an impressive debut from a promising author. Pete Redrup

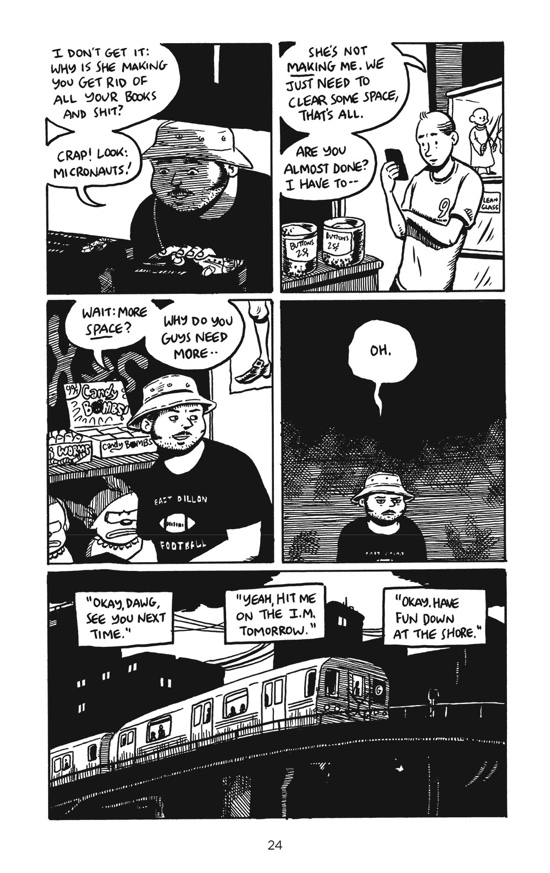

Alex Robinson – Our Expanding Universe

(Top Shelf Productions)

Alex Robinson’s latest book, Our Expanding Universe, is exactly what his fans might expect him to produce as he ages. The art is instantly recognisable – black and white, with faces very similar to characters in his earlier work. It’s refreshing the way he doesn’t resort to unrealistic physical stereotypes – his characters are often wide-faced, a bit overweight, balding, and in this book, they’re also older. It’s about a group of friends, somewhere in their 30s, and explores themes of relationships and infidelity, parenting and how friendships change through all of this. Your response to the previous sentence will pretty much determine if this is of any interest.

It’s a fast read, and it is very much a read. Many pages feature several speech bubbles per panel, often overlapping, sometimes taking up half the space. This is no different from his earlier work, but leaves little ambiguity and even fewer pauses for breath. Some pages feature flashbacks with characters integrated into the present day panels, which is an effect that works really well at filling in back story and giving depth to the characters. In other places, stylistic experiments go awry, however. There’s a section titled The Sirens of Brooklyn, which features text-free panels matched with a column of typed text in the format of a screenplay, complete with character directions such as “Julie (grimaces comically)…”. It’s a questionable decision, as this is exactly the kind of thing we expect comics to communicate visually. It certainly provides a change of pace, but it’s a relief when things return to normal.

Alex Robinson is a gifted storyteller with a particular talent for well-defined, believable characterisation in both the art and the writing. If you’ve enjoyed his previous work and have aged with him, this won’t disappoint. On the other hand, if your preference is for heroic characters and implausibly dramatic events, or ambiguous and elliptical work, this may have less appeal. Pete Redrup

Various – Kramers Ergot #9

(Fantagraphics)

The new issue of Kramers Ergot, Sammy Harkham’s considerate and enthusiastic anthology series, features several short works that are entangled in, haunted by and engaged with violence. While this is a theme of the book, violence isn’t this collection’s defining element. And in stories that do cover the topic, it’s more of a coincidental afterthought that naturally arrives through characters, settings and happenings.

Ben Jones’ one-page Tux Dog strip uses numbers to guide readers through an unorthodox panel layout. The comic shows the titular character promptly dress in a military outfit and fire a machine gun into the sky; the bullet brings down the body of a space alien a day later. The punch line lets you laugh, but the character’s calculated action to kill some other is creepy. The way Jones draws Tux Dog studying his watch, impatiently awaiting his results suggests someone who only sees the business of his action. Jones’ numbered panels add to the sense of procedure.

Scared Silly, by John Pham, follows two young women through a cemetery as they search for Bacne, a child they are responsible for. As they look, buried soldiers spring to life to initially horrify, yet ultimately befriend these women, until an awkward interaction leaves both groups cold. The comic is apparently a harmless short saturated in pink hues and rounded shapes, but Pham informs readers of a painful point of separation that stands between these parties. It’s based on differing personal experiences, such as involvement in war, and the condescending assumptions that someone can make from them. The story settles with a bad social situation, both sides confidently misinterpreting the other, but when the women finally leave the cemetery, agreeing that they’re glad to leave, you understand that a deep rift will keep them away, not simply the scenery.

Matthew Thurber’s surreal Kill Thurber makes you laugh and sweat with its ridiculous plot and claustrophobic structure. The cartoonist, sick of sharing his name with that of James Thurber, ends up in a snare of never-ending time travel, always on the quest to murder the other Thurber. He splits his six-panel pages to simultaneously show the attempted violence and the events that lead to it. Eventually, by story end, Thurber progresses both narratives to a point of collision, forming a loop, suggesting complete immersion in a reality the cartoonist has created for himself; a reality consumed by blood lust. Thurber draws a look of helpless obedience on his analogue’s face in the story’s final panel. This look suggests numb action.

Kramers Ergot #9 showcases cartoonists who can make us laugh and turn the page, who let their ideas slowly unfold after we’ve read their stories. Violence, as theme, almost works backwards. While guiding us through a certain area of thought, it also highlights the subtle marks these storytellers make. Alec Berry

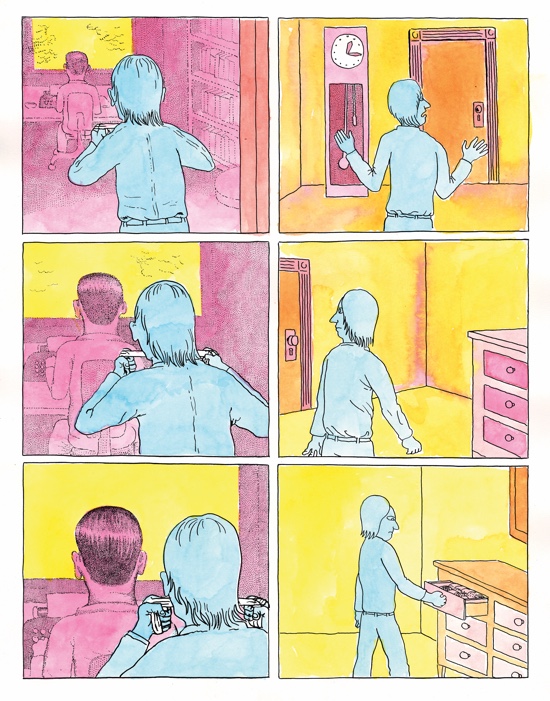

Tillie Walden – A City Inside

(Avery Hill)

Tillie Walden’s new book, A City Inside, is an ode to the ebb and flow of living; it says that growth is a process, not a matter of time.

It’s a universally appealing piece of work that operates on lyrical narration and softly sequenced imagery, demonstrating the balance 20-year-old Walden can strike within the interplay of words and pictures. She paces her story with confidence. Her pieces of prose pull readers through the book as they float in succession, yet play so well into the images and panel compositions in place, settling what could be a hurried reading.

Her line art conveys both tangled vegetation and precise city landscapes. Walden wants us to attend to the thought that we age in physical spaces, whether that be farms, beds or offices. She suggests that locations both free and confine us, and that settings once habitable can turn toxic, or vice versa. In general, her setting selections diligently illustrate this concept, but it’s Walden’s exact lines that create these settings. They imbue texture and the hand that made them, communicating the notion of participation to readers. It’s as much about where a character lives as why a character chose to live there that informs their life.

Walden’s character, a young woman, could believably be an analogue for the author, yet she’s neutral enough to represent us all. Again, the author strikes a balance. She provides the woman enough of a past, as well as a love interest to enable her to stand on her own, yet these attributes are not too specific, so that she’s not defined as someone particular. This appeases Walden’s grander interest in universal appeal while still lending some shape to the emotions within the story.

A City Inside is impressive because it says what’s on its mind so clearly, while maintaining a fluid, dream-like flow that other comics exploit to be flirtatiously vague. Alec Berry

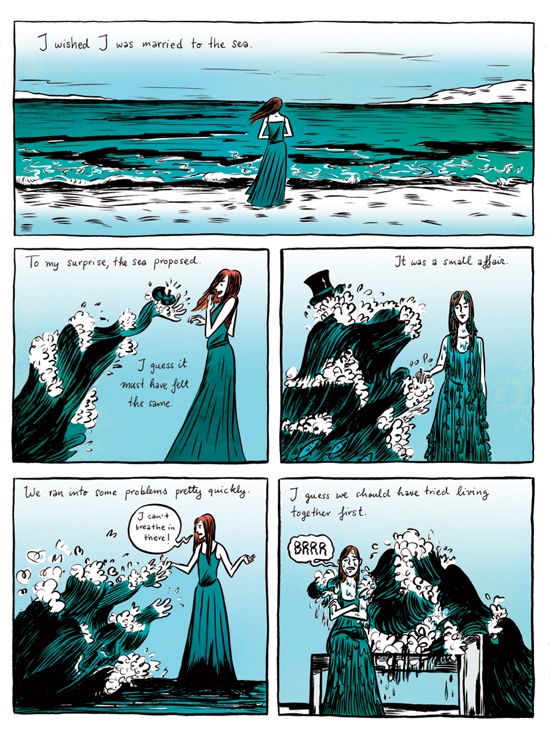

Julia Scheele, I Wished I Was Married to the Sea

(self published)

You’d be forgiven, reading Julia Scheele’s collection I Wished I Was Married to the Sea , for thinking it was an anthology of different artists’ work. Scheele has included pieces here that have different feels, different voices, as well as different visual approaches. A stalwart of the British zine and comics scenes, she also works as an illustrator and a graphic scribe and examples of individual fashion pieces and quicker, more reflexive drawings are scattered through the book, punctuating the comics and adding to the visual feast. Stories of emotionally draining ghosts and elemental spouses, wordless dreams of melting and drifting apart sit with thoughtful memory pieces.

The core of the book (literally and figuratively), Hello Again (an autobiographical crisis) addresses the thoughts and feelings behind this diversity head on, and the frankness of the author’s exploration of what motivates our impulses to confess and autobiographise, or to fictionalise and "stick with obscure metaphors" is poignant and deeply effective. Throughout the collection this dance of fantasy and reality maintains a frisson of tension, so that each detail of words or images leaves you guessing at deeper meanings. Scheele is such a master of composition, expression and body language in her work; each line does a job even in the scratchier sketchbook roughs included in the back of the volume. I would have quite liked a bit more of a division or explanation of the less realised work, but the unexplained sitting snugly with the fully explored is an editing choice which does feel authentic to the ideas behind the collection. Overall this slim volume packs a lot of punch, and pathos. Jenny Robins

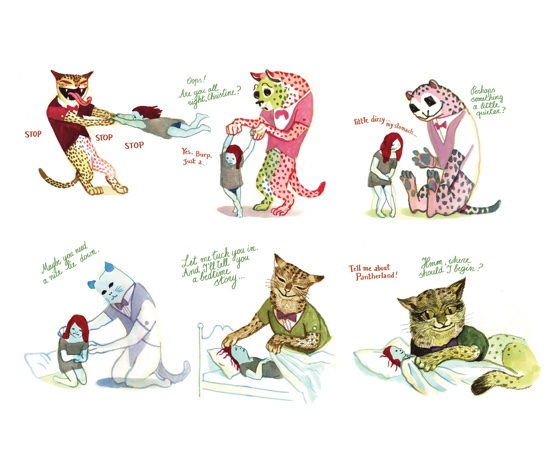

Brecht Evens – Panther

(Drawn & Quarterly)

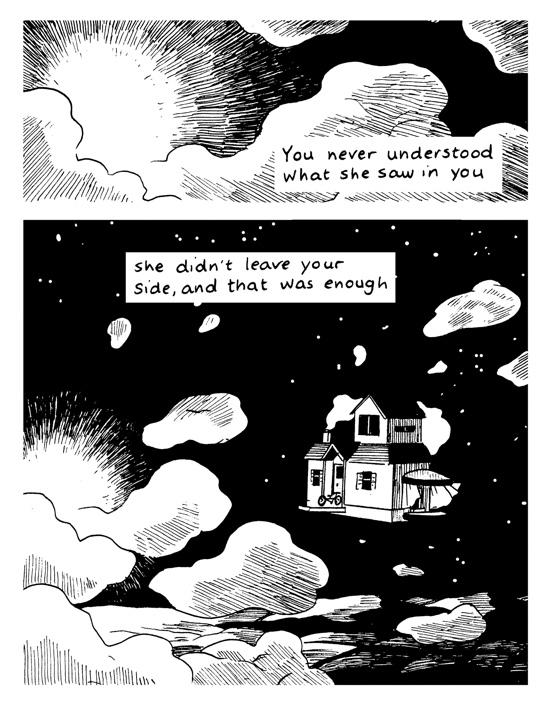

One of the biggest tragedies a child faces is the death of a family pet. Even when we grow old the death of a beloved dog or cat lingers while other childhood memories fade. Death is a powerful mental landmark leaving tombstones in our mind, and it is within this psychological cemetery that Panther by Brecht Evens takes place.

The book opens with little introduction, beginning with Christine’s emaciated cat’s refusal to eat, followed shortly by her father’s heartbreaking news. This immediacy is at first surprising, but helps to reinforce the all-consuming nature of the beloved animal’s passing. Without a word Christine rushes to the solitude of her bedroom when out of her dresser pops the eponymous Panther. On the surface Panther is like Dr. Seuss’ amiable Cat in the Hat, but as Christine’s interactions with Panther increases it becomes obvious that he is more like the devious Cheshire from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. As Christine becomes further consumed by Panther’s presence she begins to spend less time in the real world, resulting in her increased detachment from family and friends. Even in school her classmates appear like gloomy phantoms while a cat’s inscrutable gaze replaces the clock’s ticking dial.

As always Brecht Evens’ art is one of a kind. Instead of carefully crafting panel borders he lets the interactions of his characters float in empty space. This helps to make the story easily accessible since there are few distractions on the page, and also suggests the infinite space of a child’s imagination. When Evens chooses to focus on more detailed compositions he fills every inch of paper with patterns, stripes, and polka dots in an ever turning kaleidoscope of color. The design of objects, including Panther, are always transforming suggesting the malleability of Christine’s emotions, which we hope will lead to her eventual reconciliation.

Panther is a children’s story for adults perfect for both cat lovers and fans of cerebral fantasies. Matthew Laiosa

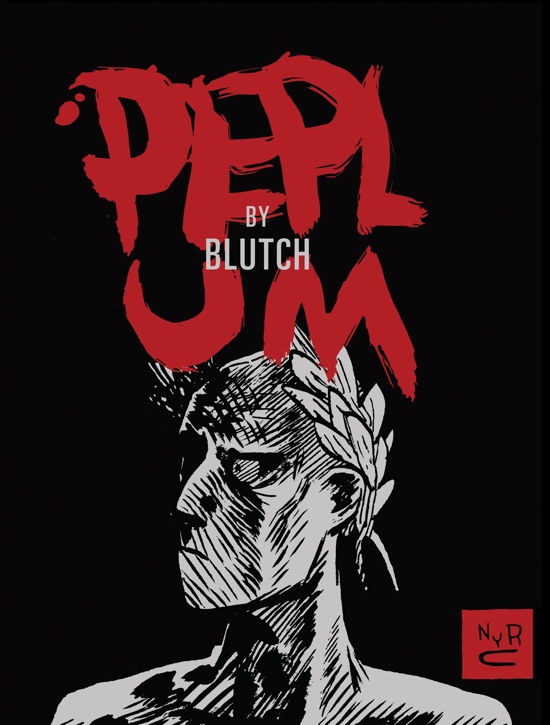

Blutch – Peplum

(New York Review Comics)

The term peplum refers to the sword & sandal epics from Italy made in the early 60s, dominated by B-movie heroes set in ancient antiquity. The comic book Peplum by Blutch shares the film genre’s sense of adventure, but it is by no means a B-caliber story. Blutch uses common peplum themes such as mythology, piracy, and Roman history, but he remixes those elements together with Shakespeare, art history, and even ballet in order to create a contemporary fable of blind ambition.

The book begins with a group of warriors’ search for a woman frozen in ice. After discovering the chilly maiden and journeying for a year with not a single drop of melted water, one of the warriors, a man of low birth, murders his comrades, and assumes the identity of a nobleman. Through folly and fortune the man will continue to lose and reunite with his glacial companion while repeatedly rising and falling from riches to rags. The episodic and meandering adventures of the main character makes the book feel more like a road movie than period epic creating an unpredictable dream-like reading experience full of mystery, magic, sex, and coincidence.

Arguably the most interesting aspect of the comic book medium is the empty space between panels. It is in this quarter-inch of white space that the audience inserts their own imagination in order to fill in the blanks therefore becoming an active member of the storytelling. Blutch pushes this idea one step further by leaving large ‘blanks’ between chapters allowing the reader to build their own story around the events depicted. This freedom will be perhaps alienating for a reader looking for a more conventional narrative, but for readers interested in participating with the story, Peplum will be a truly engaging and rewarding read. Matthew Laiosa