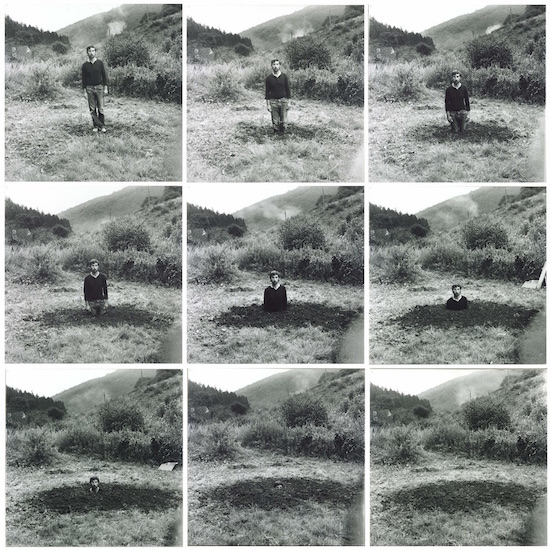

Keith Arnatt, Self-Burial (Television Interference Project), 1969, Tate. Presented by Westdeutsches Fernsehen 1973, © Keith Arnatt Estate / DACS, London

On the 26th of March 1971, Keith Arnatt decided to go to the Tate Gallery. We know this because he typed it on a piece of paper. “I have decided to go to the Tate Gallery next Friday,” he wrote. That statement, he decided, was in and of itself “operative as art-work”.

But how can an intention be an artwork? How can it be any sort of work at all if it hasn’t happened yet? And would its status as art be affected if Arnatt had failed to make it down to the gallery that following Friday?

Arnatt would say not. “To decide to perform an action X,” he wrote on a separate sheet of paper, displayed beside the first, is, he says, already, at least partly, “to perform an intention.” And further, he quotes the English analytic philosopher Anthony Kenny, “The expression of an intention in the form of a statement about the future is condemned as a lie not on the grounds merely that it is not fulfilled (not even if the non-fulfilment if voluntary), nor yet merely because the utterer does not expect it to be fulfilled, but only on the grounds that the expression of the intention is not meant.”

All of which may be granted, so long as we don’t neglect to recognise that Arnatt is also here performing a quite different kind of intention. That is, the positing of a statement about art itself and its relation to truth. Specifically, to truths about the future.

I Have Decided To Go To The Tate Next Friday is somewhat typical of the works comprising the Tate’s Conceptual Art in Britain show, inasmuch as it is rather wordy, distinctly un-ornamental, and concerned less with the articulation of space than time. It engages its audience not as passive spectators required only to gaze admiringly; but as thinking beings, having to engage with the work, make decisions based upon it, accept or reject its premises, and deal with the consequences of that decision.

Through and through, this is an art that looks forward, not back.

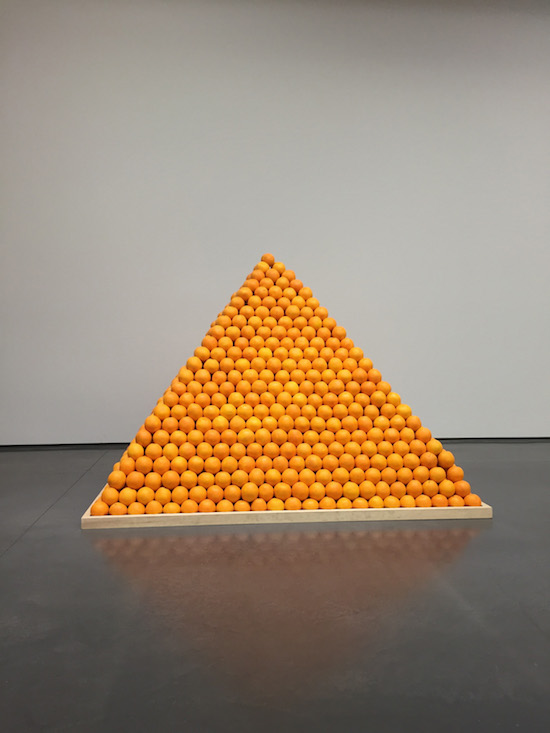

Roelof Louw, Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges), 1967, Tate. Presented by Tate Patrons 2013, Image courtesy Aspen Art Museum, 2015, © Roelof Louw

Take, for example, Roelof Louw’s Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges), which greets visitors brightly in the centre of the exhibition’s first room. This work comes with an invitation: to take – perchance, to eat – one of the carefully balanced citrus fruits of which (as the bracketed part of the title indicates) it is composed. It therefore extends through time in two possible ways: either the natural decomposition of the oranges or their consumption by the audience. The work has a life. It has a future.

Soul City has been exhibited numerous times since it was first presented at London’s Arts Laboratory in October of 1967. People, evidently, rather like being offered a piece of fruit in a gallery. But as far as I can gather, no-one has ever deliberately taken a supporting orange from the bottom of the pile such that the rest would all topple down and collapse. There is a sort of contract implied. A certain responsibility is placed upon the spectator.

“Do take an orange,” I myself was told as I arrived at the exhibition. From the slightly flattened peak of the pyramid I could see that a few people already had. “I hope you’ll take an orange home with you,” I overheard the curator Andrew Wilson saying to someone else, “I don’t want you suffering from Vitamin C deficiency!”

Several people, I noticed, here and there, clutching oranges. But I saw nobody go so far as to peel and take a bite. Did they think they were taking home a bit of an artwork, like the torn off corner of a Caravaggio? Something to treasure and preserve. There is a question, naturally, concerning at what precise point the individual orange ceases to ‘be art’. But I would venture to suggest it is probably rather before its digestion. And certainly before its subsequent evacuation (depending, perhaps, for all you Piero Manzoni fans in the house, on who is doing the evacuating).

I myself did not take an orange. After all, I had breakfasted. And it struck me that there was almost a sort of injunction, an enjoinment to partake. Feeling myself expected to take fruit, I chose instead to take inspiration from another of Keith Arnatt’s works. Art as an Act of Omission is another text-based work. “A person is said to have omitted X if, and only if (1) he did not do X, and (2) X was in some way expected of him.” Having felt myself expected to take an orange, I omitted to do so.

So there you are. I’m an artist (by omission).

Art as an Act of Omission is a work that asks questions. Some quite explicit. “If art is what we do and culture is what is done to us –” Arnatt has appended to his page, “what could culture do to us if art is what we didn’t do?” It is also a work that engages, very directly, with the future. Expectation is an essential element.

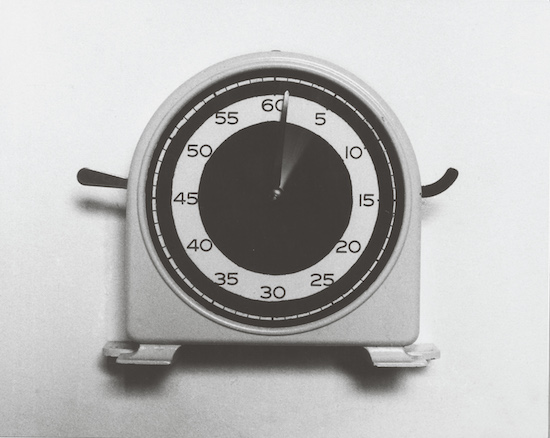

John Hilliard, Sixty Seconds of Light (detail), 1970, Tate. Purchased 1973, © John Hilliard

One year after he first promised to pay it a visit, Arnatt returned, once more, to the Tate. This time as an invited guest. 1972’s Seven Exhibitions, with Arnatt featured alongside Joseph Beuys, Michael Craig Martin, Hamish Fulton, Bruce McLean, Bob Law, and David Tremlett, evidences the burgeoning of the now long-standing commitment the gallery has had to conceptual art. Introducing the present exhibition to the assembled press corps, Andrew Wilson called his show a tribute to the curators of that era, thanks to whom he was able to access and draw on such a rich archive of work.

For his part in the Seven Exhibitions, Arnatt had initially wanted to present a work called An Exhibition of the Duration of the Exhibition which would have counted down the duration of the show in seconds from 2,448 to 0. Unfortunately, due to power cuts, this proved impossible. As an emergency measure, he elected instead to exhibit the staff cards, bearing photograph, name, and job title, of everyone who worked at the gallery, from the director to the cleaners. But after just three days, this too was removed after the staff complained (since permission had only been granted by the director and the unions, without asking individual members).

“In the early 70s,” Wilson said, “the then director [of the Tate] was beginning to extend the collection into contemporary art. And the contemporary art that existed at that time was conceptual art.”

But if today people may be too quick to conflate conceptual art with contemporary art in toto, “this is a mistake,” Wilson insists, “but only a partial mistake.” The beginning of conceptual art represented “a complete and utter break” with the past.

“It is almost as if there is a hinge,” he said, between what we now think of as the modern and the contemporary. Suddenly artists – not just in Britain, but around the world – began to say goodbye “to art defined by materials, by volume, by things that are containable.”

On the other side of that divide was a kind of art that started to seem in many ways a lot more like music. Certainly, I know very few contemporary composers who would take any issue with the claim that works like Exhibition of the Duration of the Exhibition or Soul City or even I Have Decided To Go To The Tate Next Friday were pieces of music.

And then there are works like Index 003 BXAL by the Art & Language group, which so resembles a manuscript score. Or David Tremlett’s The Spring Recordings, consisting of 81 cassette tapes, bearing 15 minutes of sound from every county in England. In such works, there seems to be quite explicit overtures being made towards music. Overtures that, today, music is perhaps only just beginning to recognise and return.

Conceptual Art in Britain asks for an unusual kind of engagement from the viewer, for an art gallery. There is very little gazing in aesthetic appreciation at works of great beauty. Even less listening. But you are asked to do quite a lot of thinking. And a great deal of reading. This is a show in which the words have left the explanatory wall panels and entered the works themselves (or at least, one in which the border between work and explanatory text has grown decidedly porous). But these words are worth paying attention to. If you listen very closely, they start to sing.

Conceptual Art in Britain is at Tate Britain until 29 August 2016