There’s an infamously perplexing line uttered by Run in ‘King Of Rock’: "There’s three of us, but we’re not the Beatles." He has apparently admitted since that when he wrote this he wasn’t being clever by noting that, at that stage, one of the Fab Four had died, but he was genuinely under the impression the mop tops were a trio. But it’s still apt because Run-DMC are as near as hip hop has come to having a group that emulated the Liverpudlians’ impact. Before they came along, rap was a music made by and for a small, localised fan base in the outer boroughs of New York. They, and Run’s brother, Russell Simmons, turned the sound and its attendant clothing, slang and presentation styles into a globally marketable commodity. The first hip hop group to appear on MTV, the first outfit to prove rap could be an albums format rather than one defined solely by singles, the first rappers to headline Madison Square Garden, tour and record with rock bands, and sign on the dotted line with sporting goods manufacturers – Run-DMC were hip-hop colossi. But not everything they did was touched by bedazzled inspiration.

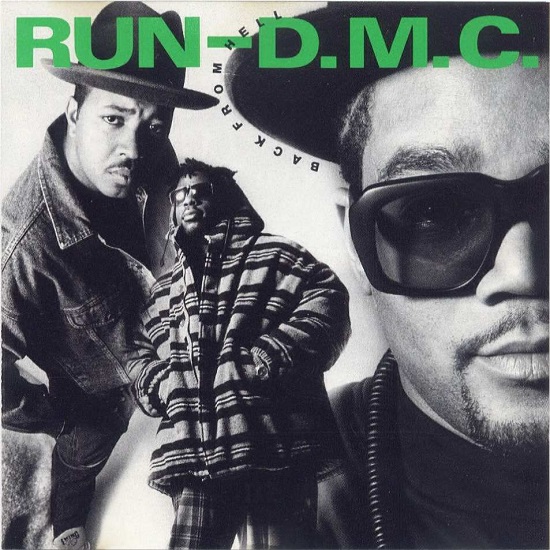

The story of Back From Hell is one of a band on a creative and personal slide. It’s a record that they made bang-smack in the middle of unprecedented turmoil and is far from their best. It tanked – by their stellar standards – on its release in 1990, and it would be three years before the group recovered sufficiently to make a record that could restate their credentials as more than just icons but enduring artists with a stake in rap’s present as well as its past. But to consign it to history’s dustbin for its – admittedly numerous – weaknesses is to ignore both the moments of real quality it contains, and to risk missing the lessons it can teach: lessons about commercial and social pressure, the workable limits of creative and artistic compromise and pragmatism, and about how even the greatest sonic explorers sometimes have to know when to ask for help if they find themselves lost in the wilderness without map or compass.

By 1990 the group were already no strangers to comparative failure. After Raising Hell, how could they not be? Their 1986 magnum opus was the kind of record that comes along once in a blue moon. Everything had to align for it to have such a profound and enduring influence: not just the music, lyrics, production, the sleeve and the image needed to be spot on – the record happened to arrive at precisely the right moment, where one of pop’s occasional mid-decade lulls meant that the mainstream was ready for a change of style. The band had honed their craft on the preceding two LPs, learning plenty about songcraft and studio technique: Rick Rubin had also found his first production voice, his work on the early Def Jam releases giving him the chops and, quite probably, the confidence to go in to the studio with rap’s pre-eminent and most assured and established band without being overawed. His encouragement that they should base the tracks on the breakbeat routines they had perfected on stage rather than continuing to root the sound in drum machine patterns and live instrumental flavouring was inspired: his urging that they should listen to the part of Aerosmith’s ‘Walk This Way’ that came after the opening drum break changed the history of pop. By 1988, any follow-up was going to be a commercial disappointment, and while Tougher Than Leather may have lasted longer than the film it was intended to soundtrack, its comparatively lacklustre sales would have been a concern. By 1990, the group may not have been in turmoil exactly, but they weren’t far off it.

The greatest thing about hip hop’s golden age was the speed at which ideas and innovations emerged and caught on. The worst thing about the period was the similar speed with which such creative concepts were labelled as passe. Very occasionally this proved to be a blessing – it meant that the wretched mash-up sub-genre, hip house, didn’t last as long as record companies, keen to find ways to promote 100-beats-per-minute rap records in dance clubs where the tempos rarely dropped below 125bpms, clearly hoped it would; though it still lasted long enough to damage more careers than it helped. But for the most part, the blistering pace of change within hip hop brought almost as many disadvantages as it did benefits. Run-DMC seem to have suffered particularly from the pressures of ceaseless innovation: and on Back From Hell – its very title an apparent reference to how this new direction would return them to the pinnacle of rap stardom they had once occupied – the trio would trip themselves up trying to keep pace with the competition. The irony being, of course, that had they thought along those lines four years earlier, Raising Hell would have had little of the innovation and individuality that turned Run, DMC and Jam Master Jay into global superstars.

Nevertheless, the album found the band making desultory run-throughs of tropes from the then commercially dominant gangsta style, and their sense of this chasing-the-market approach being the right one would have only been reinforced when the swingbeat-infused single ‘Pause’ – an intended stopgap release from 1989, which the band’s label, Profile, refused to let them release until an album was completed, resulting in it limping out on the b-side to their Ghostbusters II theme – was hailed as the best thing they’d done since the glory days of ’86. History has not been kind to ‘Pause’, or for the most part to swingbeat in general: but that was the move in 1989, and in a pre-echo of the social media age, where careers can be built, discussed, dismissed and demolished in the blink of an eye, the conventional wisdom was that Run-DMC were better off making music in tune with the times. Of course, Run-DMC at their best defined their times as leaders: hearing them follow the pack never really felt right.

Business pressures also played their part. The tortuous, frustrating and ultimately disappointing creation of the Tougher Than Leather movie had taken its toll creatively, and also left the band about a quarter of a million dollars worse off, after overruns and re-shoots required them (as co-producers) to dip into their own pockets to help keep it funded. The scrappy end result can’t have helped their mood. Although they were avid supporters of their friends and peers, members of the band became somewhat deflated by two events. Firstly, the Beastie Boys’ Licensed To Ill overtook Raising Hell‘s sales and became the first rap album to top the US charts. Secondly, as much as they loved Public Enemy’s ‘Rebel Without A Pause’ (a conversation between Run and Chuck effectively ensured the track was released as the b-side of ‘You’re Gonna Get Yours’, even though Russell had vetoed the idea) and Nation Of Millions, PE’s creative leaps also left Run-DMC feeling sidelined. According to Ronin Ro’s biography of the band (Raising Hell: The Reign, Ruin And Redemption Of Run-DMC And Jam Master Jay), Jay was so staggered when he heard advance copies of Nation Of Millions he told Bomb Squad member Bill Stephney he saw no point in continuing as a producer.

The Tougher Than Leather album suffered further delays after a protracted tussle between Def Jam and Profile over the rights to release it. Run-DMC were signed to Profile but the film, directed by Rubin and also starring the Def Jam-signed Beasties, should – Def Jam argued – have had its soundtrack released by their label. As a consequence of this, the band embarked on a Quixotic attempt to extricate themselves from their Profile contract – they’d seen LL Cool J win a seven-figure settlement from Def Jam following a dispute over the contractual status under which he’d made his first two LPs, and the Beasties had fought for their right to leave the label too. But in the end, they re-signed to Profile for an extended term with no major cash injection; all the legal wrangling had done was delay the new LP. It would eventually be released in the same month as Nation Of Millions, provoking what were always going to be unfavourable comparisons from critics and fans alike.

The response to these converging sets of dispiriting stimuli was predictable. Run became depressed, reportedly considering suicide on at least two separate occasions. He self-medicated with burgers and apple pie, ballooning in weight. DMC hit the bottle, developing full-blown alcoholism. Jay felt so certain the group was going to implode that he formed another band, with sometime Beasties DJ Hurricane and two others, that they called The Afros. Under the circumstances, that they even managed to make an album at all was a supreme achievement. That some of it manages to retain the group’s key virtues – a groundbreaking embrace of musical possibilities; beats hard enough to shake stadium floors; an unbetterable and infectious sense of vivacity and joie de vivre – makes it an almost miraculous achievement.

‘What’s It All About’ was the first single, and remains one of the more controversial entries in the band’s discography. The idea for the band to rap over The Stone Roses’ ‘Fool’s Gold’ made logical sense: in a way, it was a progression of the rock-rap-fusion ideas they’d made a part of their work from day one. The idea came from an unusual source – photographer Glen Friedman. Not being a producer, he had little sway over the recording, mixing or mastering, and told Ro that he found the end result disappointing. Perhaps because it wasn’t one of his own ideas, Jay maybe wasn’t able to give the track the kind of driven focus he brought to much of the rest of the album – there is a thinness to the sound on the track that leaves it feeling a little underdone. But the idea remains a sound one, the social-realism of the lyric sounds convincing enough, and despite its lack of commercial success (the single didn’t make the US pop chart and stalled at 48 in the UK) it remains surprising that, MC Tunes and Ruthless Rap Assassins’ ‘Crew From The North’ apart, there weren’t more attempts at melding rap with baggy. The loping beats at least made more sense than many of the far more numerous but frequently artless forced unions between rap and extreme metal.

The b-side of the single was the album’s first track, and if the whole record had been cut from similar cloth Back From Hell might have gone on to occupy a fonder place in fans’ affections. The song shows simultaneously what was most engaging about the band at this point in their career, and stands as a vivid example of why things were going wrong. The track – essentially a loop from ‘Same Beat’ by The JB’s, with a police-car siren applied to it for lengthy passages – cleaves to the philosophy behind most of Run-DMC’s best songs: it is simple in conception and majestic in execution, the swagger of the sample fuelling the track’s assured, confident bounce. Jay beefs it up but does so with a minimum of fuss. DMC gets the lion’s share of the microphone time, and since he was the one member of the group who seems to have felt, at this point in the saga, that the group’s interests were best served by giving their fans what they’d come to expect, he isn’t afraid to pattern his writing and delivery on the styles he’d become famous for. True, the end result sounds like Run-DMC trying to outdo the Bomb Squad’s productions and NWA’s streetwise sermonising, but it still feels like a Run-DMC record, and a damn good one at that.

Run evidently went the other way to his rapping partner, and his contributions to the album all too often sound like a man desperate to prove to fans and fellow artists alike that he had more techniques in his bag of rapper tricks than the shout-chant declamatory style of the group’s earlier records had shown. You do kind of feel for him – he was a far more capable rapper than ‘It’s Like That’ or ‘Walk This Way’ gave him the chance to show – and during this phase of rap history, where stylistic innovation was tied so firmly to the notion of relevance, you can understand why he felt the need to demonstrate the full range of his vocal capabilities. But the problem that results is that it leaves the group neither in one place nor in another. They sound like Run-DMC trying to do what other artists do – when each and every one of those other artists were influenced profoundly by Run, D and Jay’s first three LPs. The result is like hearing the originators trying to play catch-up with the people they inspired – it’s unbecoming and more than a little undignified. And at the same time, those several millions of fans worldwide who came to love Run-DMC through the sound and style they’d developed over their first decade would spend the majority of the running time of Back From Hell vainly scanning the record for examples of what they came specifically to Run-DMC records to get. In the end, the record tried to be something the band could never become, and in doing so failed at being who they really were.

That the title was wishful thinking would be borne out all too quickly. DMC’s addiction to malt liquor was running out of control, and an intra-band argument ensued when he turned up drunk and late to record his verse on a remix of ‘Back From Hell’ which was to prove the main selling point for a 1991 release of ‘Faces’ as a single. The track emphasised their dilemma, the group relying on the commercial clout of guests – and Run-DMC disciples – Chuck D and Ice Cube to have anything approaching a hit, yet by getting on the same track the group were on a hiding to nothing when it came to the inevitable comparisons the record forced fans to make. Run was arrested on a rape charge after a gig in Ohio but the case collapsed when a friend of the accuser suggested to the court that the allegation was made up. In fact Run maintained he wasn’t even in the state at the time he was supposed to be committing the assault. But the accusation arrived while the group were, on Russell Simmons’ advice, on strike as regards Profile, refusing to begin work on new material until terms of their contract were, yet again, renegotiated. Their bargaining position was significantly worse than during the previous contract talks with the label, when their most recent album had sold three million copies and the film had yet to open. Money was becoming a huge worry, yet by refusing to record the group were preventing themselves accessing the next tranche of advances. Jay was unable to pay a six-figure tax bill with the result that he had to pay a tranche of every dollar he subsequently earned to the government. DMC, meanwhile, spent weeks in hospital with pancreatitis.

So the record that perhaps really should have been called Back From Hell was the one they made next. They called it Down With The King instead, the name taking its cue not just from the sample from ‘Run’s House’ that opens the title track but from Run crediting his comeback from depression, disgrace and the disintegration of his family to a newly rejuvenated Christian faith. DMC, too, had sworn off booze, and had become involved in the church. Both had declared themselves bankrupt. Although the reasons for it may not have been entirely intentional (Jay apparently felt tapped out creatively when it was time to record a new album) the decision to work with a string of outside producers gave Run-DMC the chance to do properly what they’d attempted ineffectually on Back From Hell. Rather than try to assist the band in keeping pace with current rap trends, the outside producers roped in to work on the record each supplied tracks that stood as those artists’ take on how a Run-DMC record ought to sound. The title cut, produced by Pete Rock and featuring him and his rhyme partner CL Smooth, is one of the best things the group ever did, while A Tribe Called Quest, EPMD, Naughty By Nature and the Bomb Squad all contributed material that felt like it was a more organic evolution of where the Run-DMC sound might grow into rather than the kind of laboured efforts at staying current that bedevilled the previous LP.

Of course, even that wasn’t the end of their travails. DMC’s voice gave out and it would be another eight years before they released what would become their final album, one on which he barely features and had to be extensively persuaded to lend his name to. Crown Royal added little to the legend and took nearly three years to make, once protracted negotiations over guest artist involvement and sample clearance had been concluded. That it got made at all was largely down to the 1998 surprise near-global hit (it was a Number One or Top Ten single more or less everywhere the band had a fan base, except in the USA) remix of the group’s first ever single, ‘It’s Like That’. New York DJ Jason Nevins turned it into – of all things – a millennial hip-house track. DMC was well through making his first solo album by the time Jay was shot dead in his recording studio in Queens in October 2002: whether the group might have got back on track and tried to make a record in a truly collaborative way again may – like the identity of Jay’s killer – never be known, though what’s emerged about the dysfunctional process behind Crown Royal suggests it would have been highly unlikely.

Run’s solo album, Distortion, was released in 2005; his MTV reality show, Run’s House, launched the same year. He seems to have acquired a resilience this century that he could have done with during the band’s prime: the impression he gives is of stately progress through today’s very different life as opposed to being significantly more susceptible to the buffeting the day-to-day storms gave him in the ’80s and ’90s. DMC, instead, looks like he’s been jolted by each and every bump in the road, right the way back to the moment when he found out – stood beside Run on a podium following Jay’s death – that the group would never perform again. He has of late distanced himself from Checks, Thugs And Rock’N’Roll, his 2006 solo album, suggesting it was the product of a relapse into an even more debilitating spell of alcohol addiction than he’d experienced in the early ’90s. The same year as the album came out, he appeared in a VH1 documentary that discussed his discovery, around the turn of the century, that he had been adopted. His latest move is in to graphic novels: he established the imprint Darryl Makes Comics and has published three books about an Adidas-wearing high school teacher in 1985 New York – called DMC – who protects ordinary people from supervillains and superheroes alike. He’ll be promoting those in Britain shortly, when he appears at the Thought Bubble comics festival in Leeds. For him, you sincerely hope, that long journey back from hell has finally been completed.