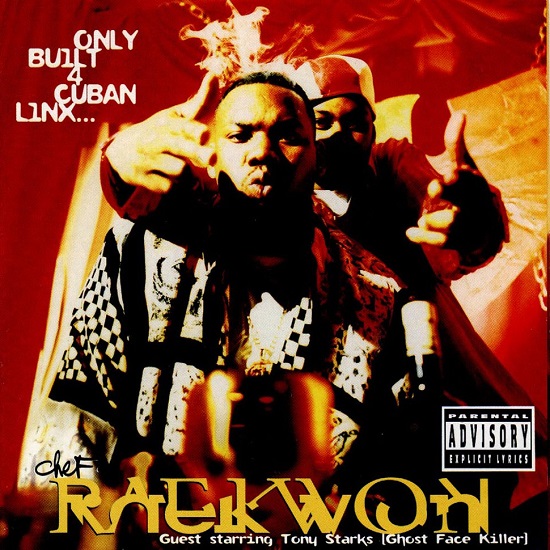

Right from the day it came out – indeed, perhaps even for a while before that – Only Built 4 Cuban Linx was special. Although Method Man and Ol’ Dirty Bastard had released their first solo LPs beforehand, it was Raekwon’s debut that finally convinced those perhaps a little reluctant to accept the fact that the Wu-Tang Clan were revolutionising rap. It included appearances from all the group’s emcees and was masterfully choreographed by b(r)and mastermind Rza. The decision to recast the group members as Staten Island crack-era mafia dons, each with a new nickname and a distinct on-record character and personality, turned what could have been just another record about crime and drugs into a piece of high-concept art that helped convince those perennially inclined to be sniffy about hip hop that this lot were on to something after all.

As a result, the album has been accorded a special place in hip hop history and the mythology around it is as extensive as it is largely well known. Tributes have come from obvious sources – Raekwon released Only Built 4 Cuban Linx Part 2 in 2009, a limited-edition box-set re-release of its iconic "purple tape" cassette format arrived in 2012, and the rapper has started talking about a forthcoming third instalment. The New York shoe emporium Packer even teamed up with Diadora to release a 20th anniversary "Purple Tape" trainer – the limited-edition run, priced at $200 per pair, sold out almost immediately. The album’s impact on the genre was as considerable as it has been controversial, many contending that its impact on the three biggest names in late ’90s New York rap (Biggie, Nas and Jay-Z) all took key elements of their signature style from Raekwon’s template. Nas, who is the only non-Clan emcee to guest on the record, addressed some of these questions of influence, debt and honour in a song (‘The Last Real Nigga Alive’ on his 2002 album God’s Son) while Jay-Z owned up to the Purple Tape’s pivotal place in ’90s NY rap history in Blueprint 3 track ‘A Star Is Born’. It has become one of the best documented records of its era, a magisterial 2005 article in XXL effectively the last word in the circumstances of its creation.

So instead of going over all that old ground once again, I’m going to devote this article to a Q/A with Raekwon from 2007. We met in Paris, where he was playing a gig, to talk for an article I was writing for Mojo, which was aiming to tell the Clan’s story ahead of the release of the fourth group album, 8 Diagrams. Sat at a tiny circular table in what was little more than a corridor-like alcove (candle-lit, wood-panelled) off a hotel bar on the afternoon of his gig, Rae was animated and garrulous – he and Rza were, as has been the case for so much of the last decade, still at loggerheads over their different beliefs in the sonic direction the group should be taking – but reflective and shrewd, and above all honest. When you’ve interviewed a few musicians you end up being able to tell which ones are going through the motions and which ones are genuinely listening to what they’re being asked, thinking about the best way to phrase the response, and giving an answer that may have been parsed carefully to ensure it’s understandable to outsiders, but which comes from the heart nevertheless. Rae definitely fell into that category. We spoke for almost two hours, broken only for a couple of minutes when he donned headphones with keen interest when I told him I’d got a mixtape on my Ipod on which Klashnekoff wrote a new rap to the ‘Criminology’ beat ("He did a great job," was the verdict: "That’s not an easy beat to flow to"). This isn’t the whole interview – much of which was specific to 8 Diagrams and the dramas around it, so is irrelevant to our present purpose – but what’s here may help fill in a few of the remaining blanks in the back story to that classic 1995 solo debut.

Let’s go right back to the beginning. Rza called a meeting, in a Staten Island basement, where he said, ‘Give me five years of your life and we’ll get to Number One.’ Can you remember that day?

Raekwon: Yeah, I mean, that was one of the best days out of my life. Number one, we all knew each other from the neighbourhood, but when we came together for that cause, it was more or less like, This could change your life in a better way, or if it don’t work, you’re still gonna be part of an environment in the streets, it’s gonna be rough like how it always was. But, bein’ that that day was so special to us that it was like… It was an opportunity to become legit, number one. I never had a job – never had a real job. I was around 18, 19. You know, I’m a product of my environment, gettin’ into everything you know a kid my age would get into, a lot of negativity was surroundin’ me. And we came, sat up and had a discussion about makin’ a record, I think I was more or less overwhelmed with just that fact. Not even more or less lookin’ at it like this is gonna be a career that I’m settin’ to do – it wasn’t like that. It was more or less like, you know, we here, y’all know I get busy, I wanna be honest. We didn’t think that this was gonna happen, all we thought was we was makin’ a record and gettin’ it on the radio. When you a young kid at that age at that time, and you know that you got talent as far as hip hop, you wanna be on the radio, that’s the first thing. So we was more or less infatuated with just havin’ a song on the radio, you know? Before our careers even launched it was more or less about lettin’ everybody know, ‘Staten Island? You got good emcees there.’

The way I understand it, you’d already recorded ‘Protect Ya Neck’ before the meeting where you formally set up the Wu-Tang Clan. That song was almost like trying out, I guess.

R: Exactly. It was like comin’ to practice – like comin’ to audition for a play. We came in there, we did our thing, Rza was already inside the business already – he had a record out in the early ’90s. Him and Gza, they was already involved with the music business. Unfortunately they careers didn’t go to the level that they wanted to be, but they kinda knew the business, and they kinda knew, at the end of the day, this is something they feel that they could really make a lot of money with, and actually help us make a career out of this. And one day they came and said, ‘Yo, we wanna make a record. We want you on the record, we want this one on the record, we want this one’. They picked out particular people that they wanted, and I happened to be one of the dudes they wanted to be on the record, because they heard of my reputation in the neighbourhood as bein’ a emcee. So make a long story short, we all knew each other, but we all wasn’t every-day friends. You know? I mean, how can I say? You know, when a friend lives down the street, but you just know him – you don’t really hang with him like that. But, fortunately, Rza had a certain kinda love for everyone he picked. He knew me, he knew Ghost, he knew U-God, Method Man: he had individual relationships with certain dudes, so his relationship allowed him to make the calls and have us all come to the table in one spot.

So next thing you know, we made the record, the record started to buzz on the radio. Kid Capri was the first one to play our record on the radio, and it kinda left a buzz in the air about ‘Who’s these guys? Who’s nine individuals that came on a record, that the record just sound so incredible?’ And I think the record allowed us to really take our craft more seriously. The next thing you know, we started to shop the record. Before, it was just a record: now we wanna do a album. And when we did the album, that’s when Wu-Tang was born, for real. That shit was really… took it to a level of, ‘OK, y’all guys is gonna get a record contract’.

At what point did the whole kung-fu stuff become part of it? Was that something that was part of the plan when Rza explained it to you all?

R: At that time, in the early ’90s, they was playin’ a lot o’ that stuff on TV, on Channel Five. It would come on Saturday, 3 o’clock as well you know? This was something that Rza had a passion for. I guess he musta loved it. I loved the karate flicks as well, but I wasn’t actually finked out about it – I wasn’t overwhelmed where it would drive me crazy that I gotta see a karate flick. He was a fanatic – I wasn’t a fanatic. But I loved it – still love it. It was his passion to come with the Wu-Tang Clan idea, with the brothers and the brotherhood. It was almost like the perfect gimmick to promote who we are today, you know what I mean? We all consider ourselves as brothers. It seemed like a lot o’ shit that was goin’ on in the karate flicks was how we felt as young kids growin’ up in the neighbourhood. Like, if somethin’ happened to you, somethin’ happened to me. It wasn’t about us bein’ karate experts, or somebody studyin’ the arts. Rza can’t even front – he never studied the arts. He just looked at the TV, looked at what he liked, and I guess he had a passion for it.

It was the mythology and the story behind it.

R: Yeah. Yeah, it was more about the discipline and the brotherhood and the slang that we was tryin’ to more or less get across to the people.

Did that translate into the way you all worked together and wrote? There’s that lyrical image of you all sharpening each other’s swords, you’d write against each other and battle in rehearsal or in freestyles, and that you’d all develop your own individual styles like the Shaolin monks did.

R: Exactly. All it was a translation of how they do they thing, as far as karate fightin’, is how we do our thing mic-fightin’. We called it mic-fightin’ before it was even called a battle or somethin’ like that. It was about testin’ your sword. Your sword is the tongue, so that’s what you fight with. You fight with your wordplay, your competition, your back against the wall as an emcee. And back then, emceein’ was about battlin’, it was about lyrical swordplay, and the thought of makin’ Wu-Tang Clan a rap group – it kinda matched perfectly. Wu-Tang was a sword style in the kung-fu flicks, and we would say that we’re that lyrically. Rza just used the whole synopsis of the karate flick and capitalised offa that around this music. Some things you find out and you compare to yourself, and you’re like, ‘Wow, it has so much comparison to it’, you start to live like that. And that’s what happened – we started callin’ ourselves Wu-Tang.

Then you made it stand for Witty Unpredictable…

R: Yeah, then we started comin’ with the acronyms that allowed it to basically make sense to us. Like when we did ‘C.R.E.A.M.’ – Cash Rules Everything Around Me – that’s the same we did the Witty Unpredictable Talent And Natural Game. We was just young guys who wanted to change. We got tired of doin’ this same everyday bullshit that we was doin’, and we all felt like we had dreams o’ bein’ a big star. You know, as far as with myself, I never really took it that serious as bein’ a star. I only took it that serious as bein’ a emcee, which is two different things. You know what I mean?

An emcee’s about the craft and the skill – a star is what comes from people appreciating that.

R: Yeah. A star’s the work – the work ethic you put into the business, and the people you excite. We only wanted to excite only a few people at that time, which was some o’ the emcees that was hot that was in the game. Our impression was to come in and be the new Hit Squad. Hit Squad was Redman and Das Efx and Erick Sermon…

I interviewed Erick and Parrish a while back and they were saying, ‘We never get the credit for the fact that we had the crew, and the people signed to different deals, before Wu-Tang’.

R: I applaud them, you know what I mean? I definitely applaud them. They so much inspired our careers that even when I see these guys today it’s like talkin’ to a god. I think they probably felt like that because they didn’t promote it like that – it just happened like that. We more or less promoted the idea, so that’s why they could never understand why people didn’t catch on then. Erick Sermon, he’s a smart producer – one o’ the illest producers in the world – and when he built his alliance he didn’t build it on top of sayin’, ‘Yo, I’m comin’ in with nine dudes’, or ‘I’m comin’ in with a group’. He came in with him and Parrish Smith; they grabbed Redman up later on, and Das Efx later on. Our thing was different because back then in the game, it was hard to put nine dudes on one record.

It still is!

R: It’s like, how could you eat with nine emcees on one album? So we kinda didn’t really care about the money – we felt like a group and we felt like we had somethin’ to prove as far as comin’ from Staten Island. When you think of Staten Island you think of the forgotten borough. You hear all the time about Brooklyn, Bronx, Queens, Manhattan, but you never heard about Staten Island, so we was kinda mad about that. Like, ‘How the fuck y’all ain’t gonna represent where we from? It’s rough out here too, and we get down – we know how to rhyme’. So we had somethin’ to prove on that level, with the negative energy behind it. ‘We’re gonna make y’all respect us’. And that’s what happened. Rza came with the five-year plan, and we didn’t have nothin’ to lose. We was like, ‘You know what? Let’s go for it. You our big brother, you gonna drive the bus’. And that’s what happened – he drove the bus, and we took it to the next level after that.

And obviously part of that five-year plan was the solo records. That first run of solo albums is unmatchable in hip hop history. Bang smack in the middle of it, and many people’s choice for the best one, is Cuban Linx. Were you aware that you were making that album, or were you just putting down tracks that somehow became that record?

R: No. I already kinda knew what I wanted to do before my album already came. See, one thing about Wu-Tang Clan is that when Rza allowed nine emcees to be on the record, he knew that each emcee had an individual belief about him. So he said, ‘Yo, I got nine different personalities – Rae rhyme like this, Method Man rhyme like this, Inspectah Deck rhyme like this…’ We all compliment each other when we’re together, but we all have different personalities and beliefs on certain things. And me? I more or less love talkin’ about the mafia world – you know, the crime syndicates an’ shit. I came from that background, so he kinda knew that that was my lifestyle.

Were you actually involved in that sort of crime?

R: Just growin’ up the streets, sellin’ drugs, tryin’ to make money to buy sneakers an’ shit like that. I wasn’t infatuated with the mafia, I was more infatuated with the mafia principles. I felt like we had a mafia growin’ up in the neighbourhood – we was our own mafia. We felt like it was a code o’ silence that you had to live by if you was considered a crew. So when Rza recognised each individual personality, he started to create personal music for these personalities that we had. Me an’ him, we had picked a lot o’ beats ahead o’ time for Cuban Linx before we actually started makin’ the songs. I already had my eyes set on a couple o’ different tracks that he made that he felt was a perfect fit for me.

Which ones were they?

R: ‘Rainy Dayz’, ‘Criminology’ – these were all made before we even actually heard the beat and wrote to it: these was already made, and these was some of the beats that I was already pickin’, sayin’ ‘I want this for me’. And really, it wasn’t like Gza couldn’ta had it, because Gza may have heard it but didn’t want it. I may have heard it and loved it and put it in my folder. So Rza had a lot o’ stuff that actually fitted each individual, but he didn’t know who may like what. So it just happened to be that I picked a certain couple o’ beats that I liked, Method Man picked a couple o’ certain beats that he liked, Ghost picked a couple o’ beats – everybody picked they own sound that they felt they liked. And we choreographed everything to fit everybody’s sleeve.

When we came with Cuban Linx, it was more about this mafioso that Raekwon is. Raekwon is like a street mafioso dude: Raekwon is a dude that grew up around drug dealin’ – this was goin’ on in my neighbourhood, so I’m kinda a product o’ that shit. So at the time that was all I knew, and that was my position – to talk about the streets. Method Man was more or less still a street dude, but at the same token, he was a more bouncy, full-on type – a rock star. And Rza was good at craftin’ the separation in thoughts, and givin’ everybody their own zone.

When I came wit’ Cuban Linx I told Rza, ‘This is what I wanna be called on this album – this is the names I want everybody to use’. Everybody made up their names just for my album! Meth was Hot Niks – Hot Nikkels. Rza was Bobby Steeles. U-God, Golden Arms, was Lucky Hands. So it kinda made my album more interesting to come with these aliases because we’re comin’ also like a mafia crew.

There have been people over the years who’ve said that Eminem’s ‘Stan’ is amazing poetry for the way he gets inside all these different characters. My reaction to that was always, ‘Where were you when the Wu-Tang were five different characters on one record?’

R: Yeah, we were storytellin’. Before I think we was emcees, we was more or less narrators too. Because if you look at the early ’80s hip hop, it was so much creativity goin’ on with artists like then, like Slick Rick, then you had Rakim, and you had these different kind of artists back then. And we was a marble cake of all these artists. So I didn’t have a problem with writin’ stories because I felt like that was somethin’ I loved to do. Even to this day, I really consider myself an entertainer-slash-narrator. I like to talk about stuff that goes on. When we finished Cuban Linx it was like, ‘Damn, this shit sound like a fuckin’ movie’. And I even used to be screamin’ my head off back then, sayin’ ‘I wanna do a movie for my album’. This was before it even hit the world, so everybody would look at me and be laughin’, like, ‘Yo, your mind is too powerful right now, your mind is goin’ too far right now, Rae’. But I’m tellin’ ’em, ‘Yo, this is a movie! Trust me! People are gonna love it! They’re gonna love us!’ But nobody really listened to me back then. They always thought I was too obliviated or whatever. But I already pictured it as bein’ a classic, and I wanted to do everything to express it on a movie level. But, you know, make a long story short, the album came out, it went gold, I think it was maybe like a week or two, the album went crazy. And after that I was like, ‘See? See what I mean?’

It was just an opportunity for me to get my time to shine. Every album that we make is always considered a Wu-Tang album. I would never sit there and take all the credit for Cuban Linx. It was just my time; it was my zone. I may have been the quarterback at the time on that team, and everybody else followed my path. But at the same token, there’s not really no ‘I’ in ‘Team’. So I don’t like to take all the credit for just that record – I always say that’s another Wu-Tang album, it was just my chamber at the time.

Also, on that record, for the first time on any of your albums, you were joined by an outside guest – Nas. He later wrote about the way that you influenced Biggie and everyone else.

R: Right. People started gravitatin’ towards that sound. It influenced the minds of certain dudes, because we were living amongst that time. I think that when we were speakin’ at it, mad dudes was able to identify but nobody was able to come across wid’ it musically the way I did. If you were a drug dealer and you had a Benz back then, you were highly respected. And that’s what influence come in from. As far as Nas, he from Queensbridge – he know dudes, he been around a lot o’ shit. And when I made that record he was like, ‘Yo, this is my dude!’ Because he could relate. And same with, God rest the dead, with BIG. We all come from these neighbourhoods where drug dealers was big, and we looked up to them, like role models.

So when I came with this record, that’s when you got Nas sayin’ this influenced his career, an’ influenced a lot o’ people’s careers in the business. Even Jay-Z an’ all that – they could never sit there an’ front on Rae an’ be like, ‘Rae ain’t tell the truth’. You know what I mean? And I think, at the end of the day, it created a phenomenal movement with the world of hip hop today, because people respect realism. And when you come from out the projects, you have to know where you came from in order to know where you goin’. So me? I’m just speakin’ about what I know, man.

After that, when you grow up in that environment of drugs and guns and people gettin’ hurt, it start to reflect your background. And I think, at that time when I was doin’ it, that’s all I knew. But as I got older in the business, I stopped bein’ involved with that, and I started to look at the world. And I said, ‘Yo, I wanna start talkin’ about everything that goes on in the world. I don’t wanna just limit myself to one style’. See, when you think of a chef, a chef is a person that cooks many different kinds o’ foods. He may make a hot steak today. You know, it seem like my name kinda fitted me: this name was given to me from the Clan, from Rza – they called me the Chef. But when you think of a chef you think of somebody that could cook – you don’t think of chef that says, ‘Yo, I make only steaks’. No. A chef knows how to bake, he knows how to fry, he knows how to sautee, he knows how to do everything that’s pertaining to food, and that’s how I felt about my lyrical position. It’s like I would say, ‘Today I’m gonna make a hot salmon. Tomorrow I make you spaghetti. The next day I make you baked fish’. This is how my lyrical content in my head was already bein’ reciprocated to the world, bein’ given to y’all like that. And I don’t think a lot o’ people still understand me, as far as knowin’ that, yo, this dude is really a lyrical genius. I consider myself a genius because, when you talk about anything and everything, you a genius to me. It’s just about makin’ it fire on top o’ more fire.

CODA: July 2009 – "a weird genius"

8 Diagrams had been and gone, so had a deal with Aftermath and about half of the initial draft of Cuban Linx 2. The mooted Shaolin Vs Wu-Tang project, touted in the pre-8 Diagrams public dust-up with Rza as a spoiler for the Clan’s record, was still not finished; indeed, may not have been started, at least in terms of what was eventually to be released under that title. But Cuban Linx 2 was now done, and was about to be released, and Rae was in London to do some press and promotion for it. In a west end hotel lobby we again spoke extensively, and I found him to be dealing in the same blend of unselfconscious openness and raw, unfiltered honesty as had been the case when we first met, and which you tend to feel like you’re hearing when you listen to the records. The majority of this conversation dealt with the then new LP and the still fragile relationships within the group, but we also spoke a little about Rae’s writing method, where fragmentary images and ideas collide to create fractured, fast-cut narratives. I asked specifically about CL2 track ‘Surgical Gloves’, and its slicing dazzle of an opening ("Surgical gloves, snubs in the grass with his blood/ Homey hold that, the four black, we back down/ Gold Jag’, Ol’ laughin’, ‘Yo, yo, what the fuck happened?’"), but the thoughts Rae replied with stand as commentary on the way he’s written from the start.

At your best I get the feeling it’s almost like you’ve written lots and taken small bits from it. One minute you’re up there, then you move to something down here – it attracts your attention and you shift. It’s like it’s visual, but jump-cuts. How do you put these things together, and where do they come from? I know they come from life experiences and things you’ve seen, but why do you put them together in that way?

Raekwon: I think that, right now, I am travelling in many different directions in my mind, on where I wanted to be. So much is wantin’ to go back, but I still gotta move forward. But I think it’s just that I’m my worst critic at all times, you know? And when I make somethin’, it may be five or ten cuts later before I actually call it what it is. I’ve always been that kind of artist. I’m gonna put myself through the sweat for it, because I think, as an artist, that’s what made me iller, is the fact that I didn’t wanna just put out anything and everything. It’s just a process, you know what I mean? I’m gonna be the emcee first, man. I’m gonna be the emcee, then at the same time I will still remain bein’ a storyteller. I love to tell stories, man. I just feel like that’s my chamber – that’s my box.

Let’s talk about ‘Surgical Gloves’: the first two lines is just four or five images banged together.

R: Yeah. I mean, it’s just a vibe, man – it’s just a vibe that we was in at that time. I don’t know – that’s just what’s comin’ in my heart. A lot o’ times I might come up wit’ somethin’ that’s nice, and I may make it quick, you know what I mean? And sometimes somethin’ that’s quickly made sometimes becomes some o’ my best shit, for some reason.

Can you give me a for-instance?

R: For instance ‘C.R.E.A.M.’ I was just tellin’ stories. Sometimes you wanna sit back an’ get an honest opinion from your friends about the direction you goin’, but then sometimes some beats just make the shit come to life for you, and be like, ‘Alright, this is where I need to be at.’ And, um, I just think overall that I’m… I’m… I’m just a weird genius too, in my own little way! I’m weird wid’ it. You know, I kinda understand where I wanna be at, but sometimes the production takes me to where I need to go.

Do you always write to a beat?

R: Nah, I always write to the moment. I’ve always been that kind of emcee. I don’t wanna come in with all the paperwork and all o’ that or whatever. That’s good when you just an emcee from off the block that really don’t have to work as hard as the next man. But when, you know… Y’all make me write like this, from, I guess, me makin’ a classic and everybody callin’ my stuff classic material – that makes me have to work ten times harder. But a lot o’ times things just happen at the moment for me: spur o’ the moment. That’s just how it goes sometimes.

I’d love to know, if you can tell me, where those lines come from. ‘Surgical gloves, snubs in the grass with his blood.’

R: Yeah! [Grinning] ‘Surgical gloves – snubs in the grass with his bloods/ Homie hold that…’ See, that right there, all that was from me visionin’ myself bein’ back in the streets with some of the most ruthless animals in the streets, you know what I mean? I’ve been around good dudes that had terrible reputations, and when I flash back to that joint, I’m just thinkin’ about how dudes was respondin’ in the streets. Like, we didn’t have no respect for anybody but the elders, if we felt like they deserved that. My friends, they didn’t give a fuck: they would sell to pregnant crackheads, one-armed mo’fuckers, no eyes – whatever. So I felt like that beat made me go back to that ruthless side of us, and when I said the first line that’s how I felt. Niggas would wear gloves just in case somebody had to shoot somebody, and we’d leave the gun, whatever whatever. That just was dudes’ mentality.

I’m always just tryin’ to give you the best story from our side of the table that you could really relate to quick [snaps fingers], and you know, sometimes I think my hardest thing bein’ an emcee is them first couple o’ lines. It ain’t so much knowin’ where you wanna go with the rhyme, it’s just that first fuckin’ line – that first line is always the hardest line for me. I think that’s just one o’ my weaknesses. To try to get that first line, I will sit there for literally two hours and just say, ‘Damn! What’s gonna be the first line?’