A singer, poet, actor, painter, and sometime pastor, Annie’s performing career started at the legendary Max’s Kansas City, where she fronted Annie And The Asexuals. Under the name Annie Anxiety she then became a part of the London-centered post-punk experimental scene that included Coil, Current 93, and Nurse With Wound, while at the same time providing vocals for dubby acts like Adrian Sherwood and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry before joining the weird folk family around David Tibet’s Durtro label, working with Antony and Baby Dee, among others.

In the late 90s, Bandez, having taken a long break from music, turned her hand to painting, teaching herself and holding her first solo gallery show four years after that in 2002. Several shows later, some of her recent work is briefly on display at the Lower East Side location of Gavin Brown, a significant New York gallery.

The work is good. Two main styles are represented in this modest collection: smaller drawings, mostly in greys and blacks, all of which are claustrophobic, expressionistic cityscapes, jagged clusters of toothy skyscrapers dense with – what else? – anxiety, and larger paintings that incorporate collage and thickly formed fractal patterns, rendered in vibrant colors and with an earthy, shamanistic quality to them, like Buddhist mandalas as envisioned by Chris Ofili. The difference in energy between the two styles is night and day, corresponding to the two cities – New York and Miami – from which the show draws its title and its inspiration.

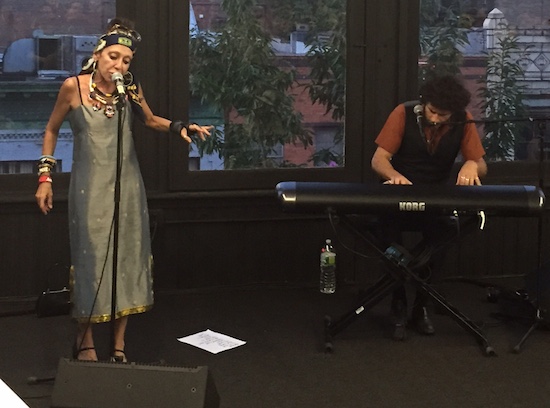

To mark the opening of the exhibition, Annie performs a 40-minute set accompanied by pianist Paul Wallfisch, with whom she has toured and recorded extensively in recent years, the material largely drawn from their collaborations, including a couple of songs from a forthcoming album for which a crowdfunding campaign was held this past spring. Annie has dabbled in many styles over the years, but her performance at Gavin Brown is in a style eminently suitable for one who has, like Bandez, lived: a bluesy, smokey chanson, full of hoarse witticisms, tenderly held notes, and wry, subtle phrasing, delivered with a knowing grin and an arched eyebrow. The performance is almost painfully intimate, the lyrics spoken clearly but low, the audience just feet away from her, the space designed for people to circulate in, not stand at attention. It is a notorious fact of the New York art world that the least significant thing at any gallery opening is the art the audience is nominally there to see, and, indeed, the rapt attention of the front rows was offset by the inane chatter in the back of the room. At one point, between songs, a guy at the front turns to yell ‘Stop talking or go outside!’, an outcry which happens to fall in the middle of Annie’s between-song dialogue. Without skipping a beat she opens her eyes wide, clutches her pearls, and says ‘OK, sorry, I’ll leave.’ This is the kind of seasoned professionalism that can come only from decades of casting musical pearls before half-drunk swine.

Lyrically, the songs are what you’d expect from a seasoned chanteuse who has Seen It All: tender portraits of heartbreak and loss mingled with incisive, vibrant character sketches, seasoned with a liberal dose of humour and resigned sensitivity. In a voice like cracked honey half-way between the agonised soul of Billie Holiday and the shattered European hauteur of Marianne Faithful, she sings tender tales of outcasts so alien even Tom Waits forgot them. It is impossible, these days, to do almost anything in New York without some mention of how Things Are Different Now. But where for most New Yorkers that mention involves hipsters griping about rent increases, for Little Annie Bandez that mention is a nonchalant anecdote about being shot twice while working at a bar that used to be around the corner.

Wallfisch is a perfect foil for this music, a strong pianist who is deft but not flashy; he is clearly the evening’s musical director, but the piano never overpowers the singing and Wallfisch leaves ample space for Annie’s energetic but lean stage presence. They have an easy back and forth; at one point Annie hesitates over the setlist, and Paul asks her intuitively if she wants to cut the next song, which she says she does, because it would be too sad, and this is a happy occasion. "But all these songs are sad," he points out dryly. They nonetheless move on to the next number, which turns out to be a gentle, waltz-y cover of Tina Turner’s ‘Private Dancer’ (Bandez and Wallfisch have recorded a covers album called When Good Things Happen to Bad Pianos).

The final song is ‘Dear John’, from her forthcoming album, a gorgeously sad, echo-y lullaby. As they begin, Walfisch stops suddenly and suggests they start again, this time with the lights off. In the darkness, the crowd is finally silent, and the echoing, repeating chorus is almost unbearably haunting; in the darkness, Little Annie Bandez becomes a ghost, conjuring with her voice and her movements a thousand nights of music and drink and drugs and beauty and dead friends who live around the corner. Then the last notes fade away and the applause is rapturous. As the light go on, I step forward and take a look at the setlist, curious what song they decided to skip: it was a cover of Jacques Brel’s ‘Ne Me Quitte Pas’, a serious candidate for the most melancholy song ever written. As phenomenal as it would no doubt have been, perhaps it’s best they skipped it; that particular song might have pushed the night’s radiant, haunted beauty over the line into pure heartbreak.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/18728-live-report-little-annie-bandez” data-width="550">