As this series has wended its meandering path through an inevitably subjective selection of albums that made their mark on your correspondent during the dog days of the 20th century, the focus has usually fallen on acknowledged classics. From time to time I’ve looked at lesser-hailed records by generally highly regarded artists, and on one occasion I’ve attempted to recontextualise an album that I felt history had been unduly generous towards. There have been a couple of times where the albums I’ve written about were debuts by artists who didn’t exactly go on to colonise the listening public’s attentions, but even in those instances the records under discussion had had an extensive and generally positive contemporary critical reception and sold in reasonable quantities by the standards of the day.

So this column’s subject is new ground for our present purposes: the one and only release by an artist that never really went on to reap the rewards of subsequent commercial success or critical acclaim; whose album made a limited impact at the time and which seems to be largely forgotten today; a group who wrote themselves into the footnotes of rap history, made it as far as sharing stages with the rap stars who’d influenced them, but whose debut sold a relatively small number of copies and who, these days, aren’t even accorded the respect of having a Wikipedia entry of their own.

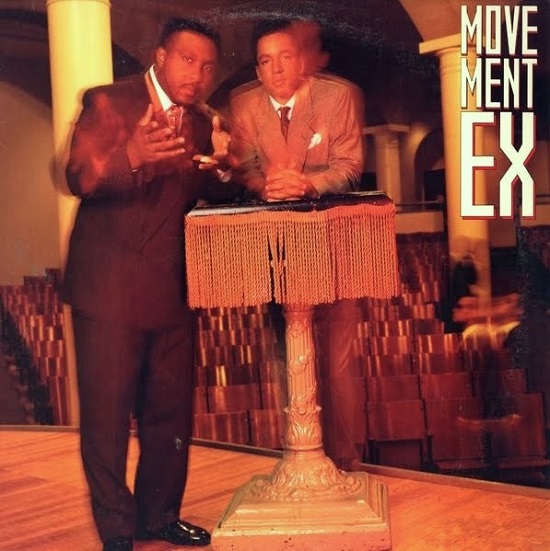

Yet if the above implies that Movement Ex weren’t important, didn’t have a significant impact, and failed to make an album that stood up to serious scrutiny, then our main purpose today is at least clear. It may be more lost classic than acknowledged iconic release, but the Los Angeles-based duo’s self-titled debut is at least the equal of the other records discussed in this series in terms of its quality, sincerity and execution.

Combining the militancy and politicised stridence of Public Enemy, a commitment to the art form and belief in its potential for entertainment and education worthy of KRS-ONE, and with something of the poetic mysticism and battle-hardened intellectual combativeness of Rakim, Movement Ex always sounded like the ultimate Golden Age group. And, to this listener, their album’s impact eclipsed many of the more widely known records that are the subject of numerous digital-era hagiographies.

(On an acutely personal level, this record’s effect was literally life-changing. When a couple of months had passed without it being reviewed in Hip-Hop Connection, the UK’s rap bible and the first hip hop magazine to be published anywhere in the world – its first edition came out before even the photocopied newsletter iteration of The Source – I rang up the office and asked if they’d like a review. The albums editor, Alex Constantinides, said "yes", and my review of it became the first piece by me on hip hop to appear outside my own fanzine. I continued to wrote for HHC until it ceased publication in 2008; the confidence I gained and the experience and advice Alex and others at the mag gave me helped me feel like this was something I could do more of. While this is, of course, of incredibly limited import to anyone who doesn’t have a surname that rhymes with 80 and live in my house, the advisability of full disclosure suggests I ought not to omit this information.)

A deeply political, unrepentantly controversial, and often blisteringly yet quietly angry record, Movement Ex was as challenging, provocative and uncompromising a statement as any that emerged during an era I’m still unable to admit has ever been topped in the art form’s history. Its sound was both raw and unprecedentedly crisp, the recording of DJ King Born’s scratches still unbettered despite decades of advances in audio technology; and the laser-like focus of rapper Lord Mustafa would have earned him an A grade for sticking to themes had Kool Moe Dee thought to add the group to his rapper’s report card. So in a way, this piece is much more important than the ones I’ve written about the canonical classics: those albums are already well known and their stories are often quite widely understood. And to tell an untold story, and hope to tell it properly, we have no option but to go straight to the source.

These days, Born Allah can be found plying his trade online, his Church Of Hip Hop And Financial Prosperity (of which more later) clearly the work of someone immersed so deeply in the culture that they’re never likely to be happy doing anything else. In the months leading up to the 1990 release of the Movement Ex album, though, he was an 18-year-old in a state of transition. For starters, he’d only found out during the making of the album that 5%ers don’t use Muslim names, so had decided to change Lord Mustafa to Born Allah. He was persuaded to stick with the earlier moniker for the duration of the album campaign, in an attempt to ease confusion listeners may have had between him and his DJ partner, King Born – but the sense that this was a period of change is an intense and noticeable undercurrent that runs through the record.

He had lived with his mother and stepfather, both members of the Nation Of Islam, in Los Angeles; but "during a period in my time when I was a very rebellious child," he recalls, his mum sent him to New York to live with his father. It was during this eastern sojourn when, attending Stevenson High School in the Bronx, the teenager came across the Nation Of Gods And Earths, also known as the Lost And Found 5% Nation Of Islam. The group, sometimes dubbed a "jailhouse religion" because of the numbers of adherents who came to it while incarcerated, and described at least once in the UK music press during the late 1980s as "a kind of hip hop version of the Freemasons", was occult and obscure at the time, unless you were a part of it or knew someone who was; for a pre-internet rap fan in Britain the idea that the 5%ers constituted an unknowable and impenetrable secret society was persuasive, if only because access to anyone who could have shed some sensible light on the topic was nil.

To hugely oversimplify, the group believe in a concept known as supreme mathematics, which permits an understanding of God and the universe through a form of numerology; and in the practice of "building" – examining subjects from different perspectives, comparing different accounts of the same event in an attempt to arrive at a deepened and holistic oversight and understanding ("overstanding") – they apply the techniques of scientific investigation to matters of history, faith and culture. The 5% Nation doesn’t hold weekly meetings in physical locations (mosques, churches, temples) and members – men referred to as Gods, women as Earths – can meet and build wherever they like. It emerged in the 1960s after its founder, Clarence 13X, left the Nation Of Islam – the bow-tie-wearing group led by Louis Farrakhan, popularised among rap fans by Public Enemy and others. Although both groups are predominantly made up of black Americans, they are entirely separate. The 5% movement’s less prescriptive approach, coupled with its prioritising of thorough investigation as the basis of gaining insight and awareness, made it particularly appealing to rappers. Rakim remains the best-known example, but 5% teachings, ideas and approaches can be found in the work of a host of the greatest emcees ever to pick up a mic.

"Being a child in the Nation Of Islam was very similar to any child whose parents were Christian," says Born Allah. "My mother and my stepfather were in the Nation Of Islam at Temple Number Seven, which was the same temple Malcolm X came out of. My father was a Muslim too, but the traditions of the Nation Of Islam are very, very strict. When I went to Stevenson High School, I saw these people who spoke similar or had similar teachings, but they were cool dudes! They were regular street kids, like myself, but they talked just as well and had the same information as anybody I’d ever respected who stood teaching from a podium. And that affected me. Wow! I don’t have to be this stiff-necked regimented guy, like a soldier: I could be a regular dude with this profound information! They were the fly-guys of the school, but they had the knowledge. They were very swift with the information that they had, they spoke well, and their magnetic was just incredible. That was something that I wanted."

Converting to the 5% Nation – getting "knowledge of self" – unlocked more than the mysteries of faith: Born Allah started to see 5% teachings he’d never noticed before, shouting out at him from his record collection.

"After I got the knowledge of self, I realised some of my favourite rappers were 5%ers," he says. "For instance, I was a big fan of Rakim: couldn’t tell you why, until I got the knowledge of self, then I was like, ‘Oh, shit! He’s a 5%er!’ Everything came after that. The light went on. You would hear rappers say all these various things – ‘All praise is due to Allah, that’s a blessing’; ‘360 degrees I revolve’ – and although I didn’t know what it meant, it sounded fabulous. Then I got the knowledge of myself and I was able to put the puzzle together."

He’d been writing rhymes and battling in school, but without any particular lyrical direction. Getting knowledge of self changed that in a trice, and set Born Allah on the path that led, unerringly and directly, to the intense political and intellectual focus of the Movement Ex album. Well, that and the influence of the best of the best.

"If I didn’t have the knowledge of myself, I probably would’ve done a real battle-rapper, braggin’-about-myself type of album," he says. "It was due to the knowledge of myself and my respect and fondness that I had for Public Enemy. At the time when we came out, Public Enemy was the end-all and the be-all. A lot of my style, and the whole album was very much influenced by Public Enemy and Chuck D, KRS-ONE and Boogie Down Productions, and Rakim; and then there would be a splash of Run DMC which is why I wanted to rap in the first place. That was really the combination of that album."

With his new immersion in the 5% Nation and his consequently expanded understanding of the hip hop records he already loved, Born Allah moved back to Los Angeles. High school friendships were to prove crucial on two further occasions. First, a friend called Tay, who used to perform human beatbox routines that Born Allah rapped over, introduced the emcee to DJ King Born. After enlisting his help to add scratching to the battle performances, the pair began working together on demos that King Born produced, the first of which – which was led by an early version of the Bob Marley-based anti-crack anthem ‘Get Up Off The Pipe’ – would go on to win them their record deal. They took the name Movement Ex, playing on the idea that their political concepts were X-rated, but with the E and the X signifying "Equality unknown".

Another schoolfriend’s uncle was the actor Mykelti Williamson – at the time, a star of Midnight Caller, a TV show about a talk-radio DJ turned detective in the mould of the BBC’s Shoestring, but later to become famous as Bubba Blue in Forrest Gump (and more recently indelible as the alternately engaging and terrifying Ellstin Limehouse in the brilliant Elmore Leonard-based series Justified). Williamson agreed to manage the band in partnership with his agent, Martin Lesack. They put the group in touch with former Cameo and Lionel Richie side man Randy Stern, who signed the fledgling group to his production company, and shopped their demo to Guy Eckstine, son of the jazz icon Billy, and then an A&R executive at Sony’s Columbia label. A showcase for Eckstine in a room in the Beverley Hills Hotel sealed the deal, and Movement Ex became the first hip hop group signed directly to Columbia.

"All of their rap acts at that time were from sub-labels like Def Jam," Born Allah recalls. "Eventually they took on RuffHouse, and the So So Def stuff came along. But back then, Columbia were in desperation to get a rap group that was signed directly to them and not from a sub-label. That kind of music was popular – that was the in thing: the shock-rap, I guess you could call it. From NWA that came out in the late ’80s up until the ’90s, that’s what the game was. So I think they were more looking at cashing in on it."

Listening to Movement Ex today – never mind listening to it back when it was new – will prompt an immediate sense of astonishment at the idea that the record could possibly ever have been released on a major label, never mind a label that once enjoyed a reputation for being notably conservative in an industry that did not prize such thinking. Yes, Columbia was the label of Dylan and Miles – it had come a long way since Goddard Lieberson had given the world its first long-playing record, and his successors at the top of the label, Clive Davis and Walter Yetnikoff, had certainly done sufficient to rid the imprint of any lingering traces of stuffiness. But Columbia would never have signed NWA, and even though the company distributed Public Enemy through its acquisition of Def Jam, it was perhaps the most unlikely label to be found releasing songs that went as deep into the causes and distribution mechanisms of racial hatred as ‘United Snakes Of America’. Yet the partnership may not have been as inexplicably counter-intuitive as it appears to the outside world.

For starters, in Stern – producing under the name Sir Randall Scott – and Loren Cheney, the producer/arranger of three of the LP’s best tracks (the record’s double-barrelled opening salvo of ‘Freedom Got A Shotgun’ and ‘United Snakes Of America’, and the 5%er meditation ‘I Deal With Mathematics’), Movement Ex had acquired collaborators capable of giving their effervescent and outspoken material an unprecedented shine – and the album’s polished production would have undoubtedly reassured traditionalists inside Columbia that they were dealing here with musicians of quality and distinction. The revolution wasn’t just being prophesied in Born Allah’s raps – the soundbeds crafted beneath the words were just as innovative, and in some respects they appear to have had an impact that was felt far beyond the 95,000 people Born Allah reckons ended up buying the record.

Stern wasn’t a rap producer and he approached the task of making this album as he would have done a funk or soul record. Consequently, the samples, drum machines and scratch patterns are each given space in the mix: there is a clarity and an uncluttered feel even to the densest and noisiest of tracks. Live instruments, particularly a full-bodied bass, are applied to several songs, taking what was implicit or inherent in the sample source material (which was already often lush and melodious: ‘Blood, Sweat & Tears’ ‘Lucretia McEvil’ fuels ‘Freedom Got A Shotgun’ while ‘Universal Blues’ is based around Deodato’s jazz-funk version of Richard Strauss’s ‘Also Sprach Zarathustra’) and rounding it out, making it sound fuller and more properly realised. It’s exactly the same approach that Dr Dre took from roughly the middle of the Efil4zaggin sessions and which, with the release of The Chronic at the end of 1992, became his acclaimed signature style: yet here’s two teenage kids and a bloke out of Cameo coming up with the same idea, yet doing it way better, a good two years earlier.

Ironically, the quality of the production was a bone of contention with the group.

"This is hilarious," Born Allah chuckles. "Just for the record, me and King Born hated how clean that album was! We were furious! But I have to give the credit to that to Randy Stern. He is the one that brung that polishedness to the album. At the time, me and King were furious about that. We were like, ‘Yo, you’re mixin’ this album for fuckin’ FM radio, man!’ Like, ‘To us, this ain’t hip hop!’ It’s so funny that after the fact, people appreciated that – but to us as young kids, because it didn’t sound like any of the hip hop we appreciated, it didn’t sound gritty and grimy like that, we hated it. Yet that ended up being the glory of the album. But that wasn’t something that these two young guys did.

"Out of all the things that I hated about our situation, the one thing that I could appreciate in hindsight was the quality level that they did the album at," he continues. "I don’t think it would’ve been so effective if it wasn’t as clean as it was, but we didn’t really have nothin’ to do with that. They didn’t allow us in to any of the mixdowns. They did all of that stuff afterwards. Once the album was mixed, we went back and forth with those guys to make sure we got certain things in, but there were certain things we had to give up – like this guy playin’ keyboards like he was on fuckin’ stage with Lionel Richie an’ shit on one of our dope-ass rap songs! Heheheh. We had to combat those certain things and we would argue back and forth. But all the polishedness and the playing of live instrumentation that did take place on that album and stuff was really Sir Randall Scott’s idea. To us it sounded like some Quincy Jones shit."

Yet even if we can accept that Columbia’s interest in the group would have been enhanced by the record’s aesthetic and its professionally applied sonic sheen, surely the lyrics would have given a corporation’s decision-makers pause for thought? This, perhaps above all other considerations, was the thing that made the album stand out when I heard it for the first time over the speakers of the late and lamented Citysounds import record shop in the Holborn district of London in 1990.

We’d had records that were extreme and deliberately provocative – Straight Outta Compton had upped the ante for its use of profanity in a way that almost made groups following in NWA’s wake feel they had to put in even more Oedipal nouns if they were going to be able to compete – but this was something else. Movement Ex didn’t take that tack – there’s a couple of "shit"s and, at the end of ‘Freedom Got A Shotgun’, one F-bomb (revocalled for the version released as a single and video), but this is a record that contains barely any swearing whatsoever and, as a consequence, wasn’t issued with a Parental Advisory sticker, the record industry’s sop to the Parents’ Music Resource Center’s campaign against explicit rap, which was still a relatively new initiative but had already been co-opted by the rap wing of the music biz and was being used less as a musical equivalent of a film certification and more like a promotional tool.

No: what was explicit about Movement Ex was the unapologetic radicalism of the group’s political platform, the incisiveness of their critiques of racism and class schisms in America, and the uncompromising nature of their proposed remedy. ‘United Snakes Of America’ called out the nation’s police forces for the kind of systemic institutional racism that the Rodney King beating a year later would put into the mainstream news space (where it has remained, of course, to this day) and predicted the role of videotapes of abuse as key to the future of the struggle; ‘Freedom Got A Shotgun’ updated Black Panther Party rhetoric and needed little explication; ‘Universal Blues’ addressed climate change for surely the first time in rap and analysed environmental destruction as an inevitable consequence of inherently racist western capitalism.

The intensity of each song often seems to ramp up as it progresses. This is in part a result of the 5% Nation influence: there’s an insistence, a determination, to examine an issue in the round – to approach it from each one of those 360 degrees. ‘KK Punani’ wasn’t the first rap record to preach the gospel of safe sex, but it was the first – and may well have been the last – to take time to examine the issue from the perspectives of both men and women alike, and not to dip its toes into the homophobia that much late ’80s commentary on what was still routinely referred to as "the gay plague" immersed itself in. The likes of ‘Zig Zag Zig’, which delves into 5% Nation teachings and learning processes, zeroes in on its subject matter with an intensity that can’t help but draw the attentive listener in.

"I am very critical of emcees who do not take the subject matter completely all the way through," Born Allah says. "And I’ve always been good at writing. Even before [taking up rap], I loved doing book reports as a child. Who loves doing book reports? But I did. I was the type o’ guy that would sit up and write my name in cursive, finding fancy ways: I just loved writing. Even in this digital era you’ve got everybody writin’ their raps with their phone – I’m still a pen-and-pad type of guy! The editing process of seeing it on paper and crossing it out and… because to me it’s almost like a puzzle, while writing your raps on a phone is almost like doing math with a calculator – it just comes out too pretty from the gate. My creative juices doesn’t roll unless I’m able to see my mistakes, correct them on my own.

"Once I get into a subject I am good at expanding on it, stretching it, taking the information and expounding on it for long periods at a time," he continues. "And a lot of that ability ended up being honed in by me becoming a 5%er and getting the knowledge of myself. By me being able to take one concept and expound on it, it becomes poetry, to an extent. If you’re standing in a cypher – which is a 360-degree circle – whatever’s in the middle is seen from a different perspective based on where you’re standing in the circle. And to me, that’s what’s unique to you. That’s what you bring to the table. That’s what you bring to the whole pie – your unique perspective. And it can go on infinitely, because we grow and we develop and we learn different things. I made a statement [in ‘Freedom Got A Shotgun’] about the Tuskeegee experiments and I said "they injected blacks with syphilis". I came to find out in hindsight that they didn’t inject it – they already had it, they just didn’t cure ’em! So, you learn, you grow, and when you know better you do better. There’s always more that you can add because you are always changing – and as you always change, your perspective always changes. And your perspective may change or your view may change in the course of one writing. It doesn’t have to be a year process: it could be a couple-of-bars process – you can start on a subject and by the time you’re getting towards the end of it you have a whole ‘nother insight of it, just off of the information you’ve already uttered in the beginning. Especially when I was young, I think the songs get better as they go on from the first to the third verse, because you’re getting better with the information as you begin writing it. That’s building. That’s growth. That’s development." A case in point is ‘I Deal With Mathematics’, in which he issues an unambiguous warning-cum-threat to the latterday Klan members and their fellow-travellers on the right, who might baulk at accusations of racial prejudice but whose positions were built on slavery’s legacy of shattered lives. The tone is patient, which makes it all the more disquieting: the closing couplet reveals this as less a thought-provoking vision than an intended indication of a forthcoming episode of preordained historical inevitability:

"You ask, ‘who is the original man?’ And I reply ‘I am.

At 200 degrees in the shade it couldn’t be a white man.’

Must know and understand: their skin has no melanin –

exposed to the light, so then he starts peelin’.

So it’s ‘Haha! I see you!’ Where will you run to?

In the wilderness of north America I will hunt you

down, like the savage you are, with the blood you shed,

with the sword of justice cut off your head.

Swing for swing, me and King do our thing –

blood pours, you lose limbs and you wonder when it’s ending

but it’s not – I keep flowing and cutting and slicing

with the fury of our past continue to rising,

with the millions we lost as my sword cuts your flesh.

Took us from the east and brought us to the west:

we was bought and sold, left out in the cold –

now I see the enemy and heads will roll.

Stole everything you got – lied about what’s true –

from red, black and green we got red, white and blue.

So to you, revolution with the finest dramatics

‘cos I deal with mathematics."

Looking back with 30 years’ growth, perspective and distance, Born Allah chuckles that the lyric is "pretty harsh". But his analysis of what he has come to believe to be Columbia’s take on it is even more startling.

"I don’t think it was a case of them thinking that it wasn’t abrasive," he says, "but to them it was like a junior version of Public Enemy. Especially when we came in to the label for the first time, when we had on our little suits and spoke our little politics, I think in a sense they found it kind of cute. You know what I’m saying? I don’t know if you’re familiar with the old TV show, Good Times? There was a character, Michael, and he was the youngest of the three children, but he was very political in a sense: the statements that he made were very pro-black. And I think they took us like Michael from Good Times, in a sense: ‘Oh, it’s cute! You’ve got these little young guys who are all into politics and their blackness, and it’s cute!’

"No-one ever said this," he emphasises, "but I think they took it like a political Kriss Kross type of thing – like they thought that we’d get over with the youth because we were so young. But the saving grace was the polish of the album and production, as well as the fact that I didn’t curse. So I gave the label a lot more room to manoeuvre in terms of promoting the album: because other than the abrasiveness of the content – which everybody was doing, because you have Public Enemy and KRS-ONE out there, so of course the labels want to buy in on that – but in a sense because it was so polished, the people were so young, and there wasn’t all the cursing, it was almost like, ‘a junior Public Enemy!’ Like a kiddie version of it: a version we could put out there without getting too much flak. They knew what it was from the beginning, because when we did the showcase for the label heads that were gonna decide if they were gonna sign us, we came in there and we’d got on our dashikis and our big wooden African medallions that we made in wood class an’ shit, you know? Heheheh. So they knew what it was already, but I think they really just thought it was a cute thing – like, ‘Look at these little pro-black kids’. Like I say, no-one ever articulated this to us – this is just the conclusion I came to over the years. ‘Cos I listen to the album in hindsight and I’m like, ‘Woah! I was on some real rah-rah shit!’ Heheheheh! And I wonder why they let that slide off in the way it did – but it took place."

The end result of those three intertwined factors – the lack of swearing; the superb production; the unprecedentedly radical lyrics – combined with the record’s relative lack of commercial success to imply a kind of conspiracy. Despite being Columbia’s only rap group, and regardless of the chart success enjoyed here by Public Enemy and LL Cool J, the Movement Ex album was never released in the UK. And its availability, even in those specialist import shops, was limited. The CD version contains four more tracks than appear on the vinyl, but it would be years before I even knew it existed. The one interview with the group to be published in the British media – by Push, for Melody Maker – noted in passing that demand for the album outstripped UK supply to such an extent that signs were posted in certain London shop windows to say that they no longer had the record in stock. It almost seemed as if the record had been suppressed – and the lyrical content could surely be the only reason for that.

From inside the group, though, this was never an issue. Born Allah recalls that there was some nervousness at the label when the FBI got in touch to ask for copies of the lyrics – but nothing ever came of that, and Born Allah reckons it was just par for the course back then. "I’m almost sure they were more concerned about Public Enemy, who had just released Fear Of A Black Planet," he says. "Other than our group being alerted by the label that our lyrics were requested by the FBI nothing else was said. Actually," he chuckles, "it was used almost as a marketing tool to promote how revolutionary we were." Certainly, there was no lack of promotional effort from the label detected by the band. Instead, those usual suspects that line up to derail careers – the departure of A&R man Eckstine; the group changing management; an understandable prioritisation of effort within the label towards more obviously pop acts – combined to leave Movement Ex falling between the cracks.

"There was just a lot of turmoil," Born Allah recalls. "I could never say that it was the content that kept us from going where we could’ve went as far as success is concerned. I think it was just a series of bad decision-making on our end as young men, and the label’s end as far as cleaning up shop of what they had going on at their company. But the press was good – I used to have a press kit with everything everybody said. We did [TV show] Rap City. We did all of the major outlets, for the most part. I hadn’t been on a major label before so I could never say that they did or didn’t do this or that, because I didn’t know what the process was in the first place. But I know that I travelled, toured all over the country – I was doing the things that I thought were supposed to take place, and even looking at it in hindsight and comparing it to what people are doing now, it seemed like a legitimate promotional cycle that we were in. Maybe the content was why we didn’t get on Arsenio Hall or something like that! But the numbers were respectable, we toured with the Def Jam acts – Public Enemy shouted us out on Fear Of A Black Planet – and we performed a lot with X-Clan, Brand Nubian, Lakim Shabazz: that was our peer group. As far as we were concerned, we were in the mix."

The record did seem to cause a few ripples to spread out through the wider hip hop pool. The first album by Ice Cube’s protegees, Da Lench Mob, is a particular case in point. It included a song called ‘Freedom Got An AK’ – an apparent response to ‘Freedom Got A Shotgun’, with the LA trio upgrading the weaponry from the lower-tech buckshot and going for the world’s most popular automatic assault rifle. But much of the nuance of Movement Ex’s carefully calibrated firestorm got lost (in the mist). Although you wouldn’t necessarily have got it from the record alone – Born Allah notes that Columbia were ambivalent about releasing ‘Freedom Got A Shotgun’ as a single until they saw his concept for the video, in which the "shotgun" that fuels the coming revolution is revealed to be books and information – Movement Ex’s intentions were to use shock tactics in an attempt to educate and persuade. The Lench Mob track, by comparison, is wild and unfocused, its primary communication mode being rage. I managed to forget to ask Born Allah about the Lench Mob track when we spoke on the phone, but he responded to a follow-up question via email:

"When Ice Cube dropped ‘Freedom Got An AK’ with the Lench Mob, I gave

him the benefit of doubt that he possibly got the idea by watching the same Black Panther documentary that I did," he writes. "But taking into consideration Ice Cube’s notorious history of biting, probably not. LoL. He was accused of biting ‘Wicked’ from a King Sun demo which led to a brief beef. He was accused of biting the hook on his song ‘Friday’ from an unreleased Cypress Hill song that led to a public feud that went on for a couple of years. He also blatantly bit Volume 10’s (‘Pistol Grip Pump’) style when he did ‘Guerillas In The Mist’ with [Da] Lench Mob. So based off his track record I guess its safe to say, yeah, he stole the concept from Movement Ex. LoL. I actually was flattered that someone of Ice Cube’s stature would bite my music, but I will admit that my friends tried hard to get me to retaliate with a dis record. I thought that it would be corny to do so because it was so after the fact. His release was two years after the release of Movement Ex."

And, unbeknownst to the outside world, Columbia stuck with the band. An option for a second LP was taken up, and the group actually finished recording it. But between the departure of their A&R man, the parting of ways with management, and the label’s clear impression that the two young men needed guidance and oversight during the recording process, the label insisted that the LA-based duo had to record the album in New York. That, coupled with the group using a portion of their second advance to buy themselves out of the deal with Randy Stern’s production company, saw the budget skyrocket.

"They were gonna drop us after they fired Guy Eckstine," Born Allah says, "but our product manager, Karen Mason, put us in touch with the new A&R guy, and let us sit down for a private meeting. He was the one that decided to give us our second shot. ‘I’m gonna give you guys this, but we’re gonna stay in control. You’re gonna do the album out here.’ We did it in Chung King [the studio beloved of Def Jam and Rick Rubin] before it closed down. Aterwards, the guy who mixed a lot of the early Tribe Called Quest stuff – Bob Power – came in and did all the mixing and everything. But just got to the point where it was over budget. I mean, that was always the excuse that was given to us: that it just became too much. So we ended up getting dropped from the label."

If the first Movement Ex album is a lost classic, the second one is hip hop’s equivalent of the yeti: there is evidence that it exists, but actually tracking it down is another matter entirely. "We completed it," Born Allah confirms, "and there are files around. It does exist. We were getting a little older and in the streets a little bit more, so it has a little more grit to it, but it’s basically in the same vein. If that album had ever come out, I think it would’ve really taken us over the hump, and we’d probably have been in the arena with some of the more classic hip hop groups that’s out there. But I think people, even if it came out now after the fact, would still be very well taken with it. I’ve actually had some offers of some people who actually want to put it out. I know King Born has some of the final mixdowns on tapes in storage. We’re considering releasing it at some level. It’s something that we have to communicate with the label and see if we can get a true release of accounts and stuff like that."

With a second record completed but buried, their contract over, the duo made like The A-Team and retreated back to the Los Angeles underground.

"Once we got dropped it was just a case of, what do we do here?" Born Allah says. "Because I can’t front: a lot of our success, and how we were able to get in the position we were able to get in was just who we knew. One person knew somebody else who knew somebody else, and it just turned into a situation when we got on a major label. And once all that was gone, we didn’t have our management company who were kind of like our lead to get to these various circles, to get to the upper echelon of companies in order to produce our product. Once we let that go, it was just like, ‘Hey, what do we do now?’ Everything else had just been people putting us onto things because we were young and talented."

King Born began producing for others – his collaboration with Chicago rapper Erule on the ‘Listen Up’ single is highly regarded, and Born Allah heard, years later, that Erick Sermon and Parrish Smith had considered the DJ as a replacement for K-La Boss in EPMD before they eventually settled on DJ Scratch. For his part, Born Allah ended up gravitating around the next generation of lyricists to coalesce in Los Angeles, becoming a regular at the freestyle sessions at the Good Life Cafe (which would become home base to future groups like Freestyle Fellowship, the Pharcyde and the emcees who went on to form Jurassic 5) and appeared in a film made about that scene. He put out singles on the Ill Boogie label before founding a group, the Tabernacle MCs, and the Church of Hip-Hop and Financial Prosperity in 2008. Last year he released a digital single with Erule called ‘Dub Fritters’, its b-side – ‘Classic’ – also featuring Planet Asia.

"With the Church of Hip-Hop and Financial Prosperity, basically we approach hip hop and give it some roots, you know?" he says. "The Bible says ‘In the beginning was God, and the word was God and the word was with God,’ so therefore we teach that God is the emcee. And God gave his only begotten son, and that’s the B-Boy – the B-Boy is the one that came to us with the four miracles, which is the four elements of hip hop. But the B-Boy has been crucified by wack rappers and bloodsuckers in the industry, so the purpose of the Church is about resurrecting the B-Boy – resurrectin’ that real hip hop, that real shit. And I’m getting ready to release a new single which really goes back to my roots as far as bein’ a 5%er and doin’ that type of music for the Nation and for my people. It’s called ‘Hardcore Righteousness’. And in the fall I will be releasing a new solo album, called Grown Man Bars."

He’s active on social media, with Twitter, Instagram and YouTube accounts as well as two different Facebook feeds. New music is posted to the Church Of Hip-Hop’s Bandcamp page. Talking about Movement Ex, even after all these years, is something he still relishes.

"My work for Movement Ex kept me in the system so that I’m always able to come out and say, ‘Hey, I got some new stuff,’ and it always makes sense – I ain’t just some old dude rappin’, I have a track record," he says "So I appreciate the Movement Ex project for that much. It was rooted enough to keep me around to this day."