It can be a confusing business, being a fan of music. You find yourself going through your listening life holding certain truths to be self-evident, only to be confronted, unexpectedly, with the realisation that more or less each and every one of them flies fast in the face of values you have come to cherish. Just when we think we’ve come up with a reliable set of standards that makes sense out of our esoteric and idiosyncratic tastes, up pops a reminder that this is art, not science, and that there aren’t any rules that can be followed.

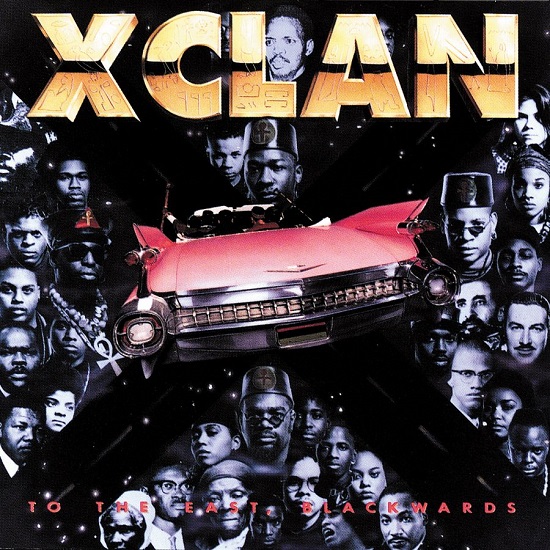

Take X-Clan’s debut album, To The East, Blackwards. The New York four-piece weren’t the first band to come out of hip hop’s golden age talking about black nationalism or rallying fans behind political campaigns; the songs on the record didn’t upend hip hop’s conventions or signal a radical new sound or style for a genre that, at the time, seemed to deal in cycles of innovation that were measured in hours, not years. In Grand Verbalizer Brother J they had a lead rapper whose voice prized clarity and enunciation over flamboyant displays of rhymecraft, and while their DJ, The Rhythem Provider Sugar Shaft, was certainly no slouch on the twin Technics, his scratch patterns didn’t sound like they were going to be passed down through the decades to be studied by aspirant DMC champions. The third member, Paradise The Architect, didn’t rap and wasn’t a DJ – his purpose, like Jairobi in A Tribe Called Quest, never quite being made clear. Least promisingly of all, the band’s ideological driving force, occupying a role to Brother J that was akin to Flavor Flav’s next to Public Enemy’s Chuck D, was a guy called Professor X The Overseer whose principal contribution to every song was to offer an impenetrable riff about crossroads, keys and sissies which always seemed to involve the made-up word "vanglorious". To say it didn’t have "groundbreaking classic" written all over it is a considerable understatement.

It was an oddity at the time, and at first it didn’t bowl you over in the way albums one will later consider landmarks often do. Sometimes its approach to the basic nuts and bolts of hip hop – the art of the beat and the rhyme – seemed almost too simple. It was determined, certainly: but its concentration on a rather esoteric take on American race relations had the effect of making that worldview come across like a kind of cultish mania. That the band appeared on the sleeve decked out in Egyptian-themed headgear, looking like rapping Tommy Coopers on a night boat to Cairo, didn’t encourage a bewildered Brit to take it all entirely seriously. And yet, To The East, Blackwards is a record that has never dated, that has remained relevant and resonant and energised: an album not just to treasure and remember, but to return to constantly for insight and inspiration. Break it down to its constituent parts and you get the sense that there’s no way it should have worked, but listen to it and absorb it and live with it as a complete work, and you gradually learn to appreciate its precision, its purpose, and its tremendous potency. Its oddities and idiosyncracies help it take flight, and its more arcane lyrical preoccupations provide a good part of the reason why it retains a timeless and universal power.

The record sticks to a formula which – depending on how inclined you are to enjoy it for what it is, and how carefully you’re paying attention – can either deepen your focus and pique your curiosity, or slowly drive you slightly mad. Take ‘Funkin’ Lesson’, the opening track, and the first single to be released after the album promotion began in earnest (two tracks, ‘Heed the Word of the Brother’ and ‘Raise the Flag’, had been released on either side of a single the previous year, but at that stage an album was an aspiration rather than a contractual obligation).

Musically, the template is set: there is some layering and collaging of samples, but the song’s structure is based around a loop from Funkadelic’s ‘(Not Just) Knee Deep’ much in the way that a modern building’s skeleton is run through with steel-reinforced concrete, while the chorus comes from the same band’s ‘One Nation Under A Groove’. This wasn’t quite revolutionary – east coasters such as Original Concept, Ultramagnetic MCs and De La Soul had all sampled ‘Knee Deep’ before – but the total reliance on George Clinton-style funk rather than the whipcrack snare sounds of the James Brown canon pre-empted and predicted the imminent rise of the G-Funk sound. So, in short order, X-Clan were vindicated, and could fairly be considered trend-setters. Brother J’s verses are delivered in a careful, almost clipped and stentorian tone, the emphasis on getting meaning across rather than impressing with verbal acrobatics – as he says here, it’s all about "bringing verbal milk, a stool and a bib": spoon-feeding the audience with the nourishment his lyrical content is designed to provide. And Professor X’s opening monologue (it’s extended even further in the promo video) follows the format he was to adopt throughout the album.

Ah yes, the Professor X monologues. These weren’t just the part of the record that divided listeners – apparently not every member of the band was entirely happy about all aspects of them, either. They’re all different, yet they’re all basically the same. In each one, the Professor will use most, or all, of a sequence of personal verbal touchstones, as if constructing a new jigsaw puzzle during each song but using only the same half-a-dozen pieces. The word "vanglorious" (not "vainglorious"; the exact meaning is never defined, but we can infer from its context that the emphasis here is on the glory, with the "van" perhaps tying that glory to being part of a vanguard) crops up throughout the album.

X frequently states that the band and their music are "protected by the red, the black and the green" – a reference to the flag of the Pan-African movement, where red symbolises the blood, black represents the people, and green stands for the land. (An attentive listener to New York hip hop back then – even with no cultural background in common beyond an enjoyment of this music – would have been familiar with that symbolism courtesy of the Jungle Brothers’ Done By The Forces Of Nature; it’s perhaps no coincidence that, before he joined X-Clan, Brother J was in a short-lived group with his schoolmates Afrika Baby Bam and Mike G.)

That protection is reinforced "with a key" – the key in question being the key of the Nile, denoted by the Egyptian hieroglyph ankh (a word J uses in some of his raps on the record), which the band members wore on top of red, black and green patches on their black fez-style hats. The Professor often speaks of "the crossroads" – a concept that tips its hat in the direction of Robert Johnson and the powerful foundational myth that lies at the roots of 20th century African-American music, but is primarily deployed to emphasise the decision-point in life that the Clan members suggest their listeners have reached, or occasionally to imply that that decision-point is the short-term destination: the venue for a party, a terminus for departure, the end of the first part of the journey and the beginning of the next. Sometimes X will talk about that journey to the crossroads being undertaken in a pink Cadillac, which on one occasion he refers to by the name Pinky. And he routinely goads those who are hostile to his and his band’s messages by referring to them as "sissies".

As the album progresses, the tone X uses to deliver these rigorously codified messages progresses from one of apparent self-satisfaction that those in the know are getting his point while simultaneously enjoying the bafflement he’s bound to be bringing to outsiders, to an eventual kind of exasperated impatience with those who’ve stuck around for the duration yet still haven’t managed to understand.

The combination of X and J – and of the brutal minimalism of the production style and musical presentation which both men arrived at in collaboration with co-producer Paradise and DJ Sugar Shaft – reaches a zenith on the blistering and shockingly simple penultimate track, ‘Verbs Of Power’. This opens with the longest of X’s monologues, which lasts a full minute before the music begins. The lion’s share of it is taken up with a list of what X sees as crimes perpetrated against blacks through the millennia – these include cultural concepts stolen and turned into weapons against black people (language, religion, art) and things perhaps less immediately apparent to anyone not intimately familiar with the detail of X’s worldview ("production of a white Kryptonite" is a powerful image to charge someone with, but remains somewhat inscrutable).

The music begins, and it’s just one loop from a single sample source – the introduction to Lou Courtney’s ‘I’ve Got Just the Thing’. Whoever unearthed this and opted to use it is a hip hop genius: it’s a brilliant decision, and quite a find. The song appears on Courtney’s rare 1967 album Skate Now/Shing-a-Ling and on the b-side of one of its less-than-huge-hit singles, and the 10-second loop X-Clan used is the only part of the song to be played at half tempo (listen to the rest of Courtney’s record, and after the snapping drum roll that X-Clan use as cover to allow the sample to return to the beginning, the song continues as an uptempo dance track).

Recorded during Beatlemania but without access to Martin-esque studio facilities, Courtney’s lo-fi aesthetic, which feels ramshackle but avuncular on the original record, becomes portentous and foreboding as the foundation of a rap track. The sound of the guitarist marking time by scratching the plectrum over damped strings on the original takes on the character of chains being dragged across a wet concrete floor in ‘Verbs of Power’; a loping pre-song bass motif morphs from the soul song’s preparatory amble into a monstrous hip-hop slouch. And on top of this unchanging, unadorned loop, Brother J shows why those who study such things still regard him as being worthy of a place among the greatest of the truly great emcees.

Throughout the album he is fastidious in subsuming his ego to ensure the focus remains on the words, not the person rapping them – quite a notable accomplishment, and a rare skill in this most brash and self-promoting of genres – but there’s a brief moment in the first verse here where, if not quite letting himself off the leash, he perhaps plays it out a little bit to give us just a hint of a glimpse at his considerable capabilities:

"Revelation to Genesis, something you cannot dismiss

Keys to crossroad, come to abyss

And find a verb-stick swingin’ while I’m livin’, givin’ the rhythm

Heed the word, and the bass drop given"

He ends that stanza with a quatrain that’s worth quoting in full, for the way it spells out the purity of his lyrical intent and emphasises that the job, as far as J was concerned, was to communicate first, entertain later:

"Look at the wax, it’s hieroglyphic, it’s actual fact

I’m not reading and striving to wanna be black

Here’s the move ‘cos I see none:

I never boast, I never brag, I get the job done"

J’s lyrics are a bejewelled treasury of allusion, metaphor and poetic vision blended with precisely delivered and sharply focused lines so direct they’re incapable of being misread. The mysterious and enigmatic stuff is vital to ensure the bald statements of intent have something to rub up against and gain purchase on your attention. You can’t have one without the other, even though some listeners would have preferred something more straightforward at times. For that spoon-fed verbal milk to slip down easily and start to go to work on the listener, it had to be served up as part of a mouth-watering dish. But the intriguing exotic ingredients J brought to his raps weren’t just seasoning: they formed a vital part of the nutritional content too.

He’s also a master when it comes to revealing big pictures by pointing only to tiny details. Two examples, both from ‘Verbs Of Power’s second verse. The stanza begins with Professor X asking a question of his fellow band member: "Brother, Brother, Brother – how you make ’em get down?" J replies: "Professor Overseer, I got pimp in my crown/ It was pimp that drove the mountainous elephant/ It was ignorance that made this irrelevant." Several things are going on here, but what’s striking is how J encourages the curious listener to dig in to the layers of meaning.

Firstly, and most simply, the exchange is about how X-Clan’s music works: Brother J tells Professor X that he tries to make sure listeners remain interested in the records by delivering his performance with a little bit of the flair and showmanship of that contentious late 20th century black male archetype, the pimp.

He then goes on to say that the ingredients of the proud pimp strut have been essential parts of black male identity for centuries, but its contemporary packaging, where it’s only considered to have a role when amalgamated into a skillset belonging to a widely despised criminal element, has removed the concept from its roots and ensured it can’t be understood.

He makes the point with a clear – if deliberately oblique – reference to Hannibal, the Carthaginian military commander famous for taking an army across the Alps in 218 BC with the aid of elephants. The inference is that Hannibal – an African engaged in a war with the then dominant world superpower (and by evoking Hannibal and his relationship to Rome, we are clearly being asked to consider X-Clan and their stance regarding the power structures of Washington, DC) – relied on the same combination of self-confidence and enjoyment of not just acting but looking the part that a pimp, or a rapper, uses in the present. And by doing that, J encourages us to see more strongly the links between X-Clan’s one-of-a-kind version of Afrocentrism and the pre-Christian black cultures the group reference in all aspects of their art (and the way that art is presented).

To complete the cycle of accelerating flourishes, he does all this in a couple of dozen syllables that arrive inside your head in a little over seven seconds.

Not content to leave your head spinning through all that, moments later he talks about Ronald Reagan’s deeply controversial visit to a German cemetery in 1985, where a number of those buried had been members of the SS. It’s the incident the Ramones wrote about in ‘Bonzo Goes To Bitburg’ – that title containing references to a 1951 film in which Reagan had starred alongside a chimpanzee and the town in Germany where the cemetery was situated. But J never mentions the former president, or the German cemetery, or dead Nazis – indeed, he mentions the divisive trip in a completely different context, to contrast the Reagan administration’s apparent willingness to honour dead racists with its reluctance to do anything to bring down the Apartheid regime in South Africa. The line is: "I said ‘Free South Africa’ – you went to Berlin" – but all that resonance is there.

J was precocious – the baby of the group, he was still a teenager when the album was written and recorded. It was clear he was building on more than just individual talent, and it’s also clear that his grounding in various elements of what came to be X-Clan’s lyrical content would have come from Professor X. But there was a wider informal education system at work, too. Before there was a group there was a political movement.

Blackwatch had been founded by X, who, as the son of Brooklyn black nationalist and political activist Sonny Carson (whose 1972 autobiography, The Education Of Sonny Carson, was made into a 1974 film), was steeped in the traditions of militancy and protest. He and a friend – later to become Paradise The Architect – were, by the mid-1980s, movers and shakers in the rap business, middlemen between artists and the Latin Quarter venue in Manhattan where the vibrant early Golden Age scene took off. Sensing that this music could be a potent vehicle for social and political polemic, X looked to Blackwatch for rappers. There were plenty to be found, but it wasn’t until Sugar Shaft, a friend of Paradise’s, introduced the teenage Brother J that a group was formed.

Afrocentrism was still an emergent concept in hip hop as X-Clan coalesced, but Professor X’s take on it was unique within the genre. He’d spent time in the Egypt rooms in New York’s Metropolitan Museum and had begun to study ancient Egyptian culture. Brother J’s dad, who died during the making of the album, was a Freemason, and had schooled his son in elements of the craft’s hidden lore. Stir in the protest politics, the anti-drug activism of Sonny Carson, and the ideas about pimp style and that there was no more fitting a symbol of indomitable swagger than a black man driving a pink Cadillac, and you had a worldview like no other. And on this album, X-Clan succeeded not just in putting it all together, but in making you believe in it and feel its pulse.

‘Verbs Of Power’ is an extreme example, but there is enough evidence elsewhere on the album to shows that its dextrous combination of musical simplicity and poetic depth, deployed with precision in a mix that allowed Brother J’s voice to stand proud above the beats, was entirely deliberate. This album doesn’t deal in the kind of dense sound-bed which words have to fight to escape from: the music works like a frame, surrounding the lyric and focusing the ear on what’s being said, and what’s being meant, almost to the point that, when listening to it, you realise you’re not actually hearing the track because you’re too busy concentrating on what it means. It might sound self-evident or even banal to praise an album for doing what, one might have assumed, all vocal records really ought to be setting out to achieve. But things can get complicated where art and ego and money are involved. Plenty of artists adhere to the dictum that "less is more", but if a few more of them would put it in to practice, we’d hear a few less bloated and self-serving records.

Another fine example of this approach in action is the album’s second track, ‘Grand Verbalizer, What Time Is It?’ Yet even here, where musical simplicity serves to emphasise and amplify the content of the vocal, the potential for misunderstanding was so strong that at least one listener – who would go on to become arguably the biggest star hip hop has ever seen – would read malevolent intent into a statement that was merely a fact given a little poetic spin. The line was "How can polar bears swing on vines with the gorillas? Please!" and the listener was a Chicago kid who later became Eminem. In a mid-2000s interview with Rolling Stone, he explained how X-Clan had made him feel excluded, had led him to believe that they felt whites had no place in rap. To be fair to Em, there are some none-too-subtle digs on …Blackwards at 3rd Bass, the primarily white New York trio; though by the same token, there’s no critique of the Beastie Boys, who Brother J would later say he felt were a perfect example of a rap group presenting themselves to an audience in an honest and real way. The image Eminem bridled at seems pretty straightforward: a polar bear isn’t equipped for life in the jungle, just as a gorilla isn’t going to last too long inside the Arctic Circle. It’s not as if Brother J is even arguing that whites and blacks should stick to their own lanes – something that, perhaps, a white rap fan so ill at ease with questions of race that he would wear Afrocentric medallions (as Eminem did) could infer from the line. Rather, what’s being communicated is the idea that you shouldn’t try to be something that you’re not. The mystery of how anyone could take a racist message from the line only deepens if you listen to the backing track. If he’d been trying to say that white artists ought to stick to definably white music, Brother J would hardly have chosen to do so over a sample from the Average White Band.

The other beat that comes from a white artist underpins probably the album’s greatest track, and the song where the album’s key theme – and its continued timeliness – is made manifest. ‘A Day of Outrage: Operation Snatchback’ was written by J on his way back from the event it depicts: and it’s the themes it dwells on, which run throughout the album, that have (unhappily) helped ensure this record’s continued relevance.

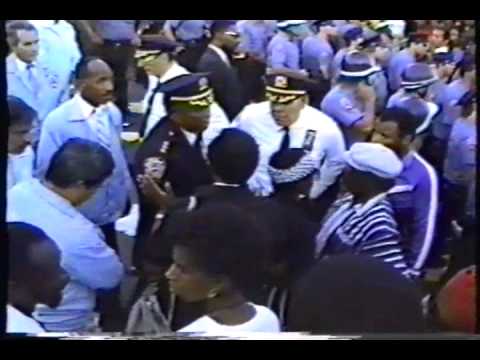

The Day of Outrage was a demonstration organised by Sonny Carson and attended by many Blackwatch members on August 31st, 1989. It was convened to protest the murder eight days earlier of a black teenager, Yusuf Hawkins, though protesters were also encouraged to remember the murder of the Black Panther Party co-founder, Huey P Newton, who had been shot dead in Oakland on August 22. Hawkins had gone with three friends to the predominantly Italian-American neighbourhood of Bensonhurst to look at a car one of them was interested in buying. They were attacked by a mob of white men, several wielding baseball bats. Hawkins was shot dead. Three days later, when around 300 black protesters had marched peacefully through Bensonhurst, whites waved watermelons and shouted "n*****s go home".

Carson’s protest saw black demonstrators briefly succeed in closing the Brooklyn Bridge: a confrontation with police – who had not been involved in Hawkins’ death but were held by many among the protestors as complicit in it, and who were an unstated but clear secondary target of the demonstration – left a reported two protestors and 44 officers injured. Afterwards, a Brooklyn pastor told the New York Times: "’I don’t know who threw the first what, who swung the first what. But it needs to be put in the context of all the years that we have been subjected to the denials, the oppression, the brutality and the killings. What took place on the bridge was measured, and the wonder of it all is that New York has not exploded."

Hawkins’ murder was referenced widely in hip hop – perhaps the most high-profile example came in Public Enemy’s ‘Welcome To The Terrordome’, where Chuck D said that "nothing’s worse than a mother’s pain of a son slain in Bensonhurst" – but with their proximity to the Day of Outrage and the fact that they were there for the protest, it is fitting that X-Clan made the record that defined the reaction to Hawkins’ death and gave it its place in hip hop history. Brother J’s encomium is masterful. The words are precisely measured, the anger kept on a simmer without ever boiling over, the passion and the fluency perfectly balanced, Billy Squier’s pugnacious ‘The Big Beat’ a superb choice to convey both ferocity and the control needed to direct it accurately.

"I bring a little taste of the unearthed bass/Problem with the truth? Then bring it to my face," he snarls: "I’m outraged as I write the page." The second verse puts you at the heart of the melee – "Walking through the streets with the great war cry/’had enough and not another one dies’…constant walkie-talkies and the squealing of pigs:/’The n*****s don’t have permits and they’ve taken the bridge!’…fist up to get down, always ready to step/and if you hit me with that stick, yo man, I’ll break your neck."

Professor X rises to the challenge too, with his finest performance on the album. "No justice, no peace" is added to his slogan lexicon, he promises racist thugs (in or out of uniform) "a Nat Turner lick", and his evocation of the crossroads – in this case, it seems, perhaps referencing not a metaphorical destination but the point where the road to the Brooklyn Bridge meets the surface streets, where marchers and police squared off – becomes a simultaneous warning, instruction and recording of folk history. The track begins with Professor X’s exasperated sigh, a wordless exhalation that carries more weight and meaning than some artists’ albums. "We’ve been here before," he notes later, amplifying the non-verbal point made at the start of the song: "The background then – the pyramids. The background now – the Statue of Liberty."

And every year – possibly every single month – since it was released, the message and the sentiment has needed to be restated. That impatience with the slow pace of progress, that sense of being unable to redirect the flow of history as it rushes onward, has never felt misplaced or overstated. Despite the precise specificity of the song and of much of the rest of the album, this is why it has not dated. The problem set has not changed; nothing has been solved; and yet the need to continue the struggle against oppression, brutality and racism has never been questioned, the effort never abandoned, the battle never declared lost.

A short while later Ice Cube would do something similar in ‘We Had To Tear This MF Up’, his account of the riot that followed the acquittal of the police officers videotaped beating Rodney King, but those remain exceptions: dispatches from the front line, where rap was not merely at the vanguard of America’s national conversation about race, but rappers were among those on the barricades, participating in the revolutions they were writing about.

And that’s why, when you’re reading about the riots in Ferguson and Baltimore, about the grief at the death of a 12-year-old boy in Cleveland, the killing in Tulsa or a man being shot eight times in the back in South Carolina, To The East, Blackwards says more and makes more sense and much more directly addresses and explains the mood and the issues and the path ahead than almost everything contemporary hip-hop can muster.

Tellingly, crucially, these songs offer a solution – study history to better know yourself (something all listeners can take from this record, regardless of their ethnicity), build some pride and self-awareness, learn to master your emotions and never let the heart rule the head – which seems to be entirely absent from media reports of the ongoing public discourse between American police forces and the people they are supposed to protect and serve, between communities and the politicians they elect (and that goes for other nations, and on a far wider range of issues, too). It is surely not what any of the band members planned when they wrote it – and neither Professor X or Sugar Shaft are still around to ask – but 30 years on the relevance and sense of urgency of these songs has never felt more needed.