In the 24 hours prior to me starting this essay, Barack Obama led a group of mourners in singing ‘Amazing Grace’ and Bree Newsome sang the same song while a flag memorialising death and oppression was taken down. It was a time, like so many other times, where saying anything directly felt unnecessary. So many others, for whom the pain and the pleasure was truly being shared were telling their own stories instead. (Consider Greg Howard on Obama’s speech and song, merely one reflection of many; consider Newsome herself two days before her action.)

More times than I can count lately, I’ve experienced the simple feeling of doing things – via RTs and links – that essentially state (albeit without saying it explicitly): "Why in the hell are you listening to me, why in the hell aren’t you simply reading and understanding and taking it in yourself, reacting TO that?" (One friend who in many ways is very different from me tried to start a debate with me on something when I had to stop him and point out his argument was with the author and other friend I was quoting – and that by trying to address me about her thoughts, he was ignoring and removing her from the conversation, not to mention addressing a fellow white guy about a black woman’s words. Thankfully, he took the hint.)

The idea that America can’t listen to itself properly has a framing which is terrible and limiting. It has a gaze that only focuses inwardly to see what it already knows, so the stories and images must be shared again and again. To call what I do anything close to activism is an insult to those who do that work, but to provide a self-erasing focus for those that need and deserve the attention, who need to be heard and seen, is its own silent if absolute bottom-of-the-list-in-terms-of-true-work calling. Which is why saying a lot more here about an album celebrating its forty-fifth anniversary this year than I have directly elsewhere about current events may feel perverse, but at the same time, there’s a goal here to share another voice. Or rather a multitude of voices, following one key voice perhaps. When it comes to Funkadelic in their amazing 1970s pomp and circumstance, it’s pleasure acknowledging the pain; it’s celebration and sorrow and something that, like the past few days, takes in human emotions and makes the point of a humanity that will not be silenced. And, much like this weekend of officially acknowledged joy following the Supreme Court decision on gay marriage, it is ever a party, and with a real freak flag flying high. Because what else can you say about an album like 1975’s Let’s Take It To The Stage starting with a song called ‘Good To Your Earhole’ that has a lyric like the gleefully sung: "Mashing your brain like Silly Putty!"

The story of George Clinton’s at once chaotic and carefully-controlled mob of inspired geniuses is something that I can’t tell in the space of one appreciative essay. They brought the party so well that too many people missed the forest for the trees and only saw the party. It’s also true that being only four years old at the time I couldn’t tell you anything about the impact of hearing Let’s Take It To The Stage, the band’s last proper album for Westbound before making the leap to Warner Brothers (even as Parliament kept on over at Casablanca), or anything from P-Funk as a whole, when it came out. (I only first heard of Clinton himself a couple of years later, seeing the famous photo of him riding the dolphins, wondering what the heck was up, as much of a, "Oh… this is music?" moment as knowing that Kiss were out there, in all their make-up.) The full story of who was in, who was out, who did what, and what they did or didn’t get at the hands of their label, or from Clinton himself, takes more time than the simplest of retrospectives will ever allow. The fact that Eddie Hazel himself, the genius guitarist of Maggot Brain and so much else, was barely on this album due to being in prison is its own individual reminder that it was never as simple as the name.

In Hazel’s absence, the other players just continued to shine. Garry Shider’s space-out guitar solo at the end of ‘Good To Your Earhole’ is a classic example – in a just world, it would be the type of thing people would talk about instead of whatever bit of stodge Eric Clapton was crapping out at the time (and that’s before we mention his racist tirade live on stage the following year). ‘Baby I Owe You Something Good’, meanwhile, has the kind of strident dawn-of-metal stomp and moments of electric balladry that, combined with gospel-driven vocals – call and response in perfection – that makes you wish for a world where it was given as much play as somebody like Ted Nugent. Plus, add in another solo that’s out to access the levels of power and beauty that actually makes a guitar sing instead of being something for a stupid dude (and it is always a dude) to wank with.

There’s also a sweet economy throughout the album. Six of its ten songs are three minutes or less and one, and ‘Get Off Your Ass And Jam’ – only one of the core dance songs of 20th-century humanity – is barely two minutes long. It’s almost like the album was a series of tasters for the live celebrations the whole collective was up to, just enough to make you go "whoa!" before you were off on the next trip, the next groove. ‘Better By the Pound’s quick, uptempo punch slides into the slow jam queasiness of ‘Be My Beach’, Bootsy Collins making his debut with P-Funk with a simultaneously here-and-totally-gone vocal that makes you just want him to keep talking until the album runs out and beyond.

Then again, it’s not like everything here is a perfect time. It would be easy – too easy, WAY too easy – to handwave one song in particular. Perhaps it’s appropriate from a distance that ‘No Head, No Backstage Pass’ sounds like a really bad trip, a distorted funhouse of a rhythm that could be two songs playing at once if still in perfect sync. Still, it’s a world where the performers are guys, the groupies are women, and the leering results may be a mutual transaction, but it’s still pretty annoying to think about, even more so these days in a world of festivals where, say, Glastonbury is yet again, another sausage fest. Similarly on the title track, when the twisted nursery rhyme variation of Little Miss Muffet smoking out and the spider showing up to ask, "What’s in the bag, bitch?", it’s pretty obvious that the Andrew ‘Dice’ Clays of the world stopped there rather than taking into account the fun and deeper layer of the James Brown-referencing chant: "Say it loud, I’m funky and I’m proud!" Then again, who knows exactly how to describe the goofy insanity of ‘Atmosphere’, which concludes the album, clocking in at over seven minutes long. Its introduction is longer than most of the other songs themselves, featuring a duet of Bernie Worrell as the organist for a roller rink that appears to be run by Count Chocula (hey, when an album has a vocal credit for a werewolf, why not?) and Clinton muttering some shaggy dog story of "dicks and clits".

But sometimes the humour is just trash talk of the most simply hilarious nature, thus the title track’s "Hey Fool and the Gang! Let’s get it on! Let’s take it to the stage!" And yet to follow that song up with weird electric noises, a triumphant drum part practically summoning the dead to the dancefloor, then a full-bodied group shout of "SHIT! GODDAMN! GET OFF YOUR ASS AND JAM!" and there’s your lyric and do you even need any more? Does anyone? You hear it and the song fade out far too soon after that – it originally closed side one upon release, there really was almost nowhere else to go – and it’s like you’ve been cheated still. It’s low on the priority list of humanity’s needs, granted, but someone should fire up one of those change.org petitions to demand a version that runs at least an hour, if not several.

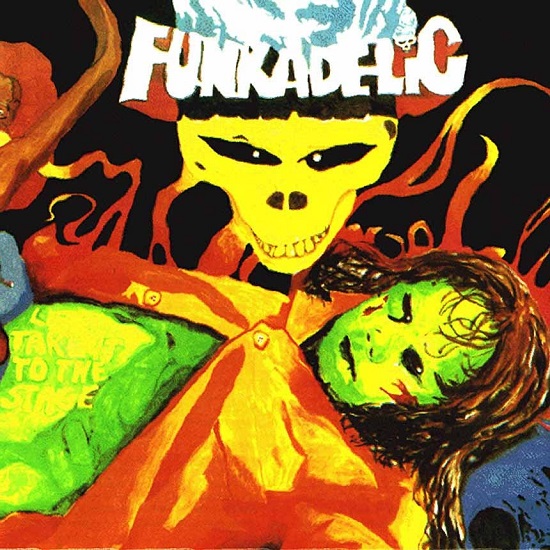

That all said, what’s the first thing encountered if one finds this album? A skull. Pedro Bell’s artwork for Funkadelic, its beauty and extremity and perversity, is maybe only approached by Mati Klarwein’s work for Miles Davis if fed through a funhouse and even more drugs. It is its own tale of great heights, empty eye sockets, bared teeth and a rotting, green corpse, and it is the type of thing that’s worlds away from the presumed rainbow disco-light hedonism that collective memory desperately wants to reduce the 1970s to. (If anything, having a grinning skull entity as a front and centre art focus predicted the near-future emergence of another bass-driven, guitar-solo-friendly collective mob of distinct players driven by one focused creator and with a core visual and logo identity – and like Clinton himself, Iron Maiden aren’t done with this world yet.)

But death isn’t in the art alone – it’s in the liner notes. And it’s not just a question of the Grim Reaper coming for us all in the end, but the spectre that loomed over a people never fully invited into a set-up which promised life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Funkadelic liner notes are their own beautiful and perverse tales of what’s happening now, and 45 years later some things haven’t changed but the specifics. Vietnam’s horrors and impact bubbled up more than once in Funkadelic’s run, and in the year of the war’s final grinding conclusion, and with the sheer self-butchery of Cambodia to come, the purported speaker at George Clinton University in Stinkfinger, Alabama talks of "the star-spangled Kong of Babylon […] unleashed to bully tidbit morsels of faraway lands. And one dawn’s light brought the greedy presence forth, to confront another, the Commie Crudzilla." Not to mention "a young mortal named Ali, who was indeed the greatest… whupping heads between signifying. But, it came to pass that the law of the land did declare that he would be obligated to exterminate strangers in an unknown land. Ali refused to participate in the wrongful bloodlusts, and he was punished and lost his boxing title."

Whenever people say the 70s was simply the me-decade, it’s because they’re trying to forget what really happened in its run-up, and who was being targeted in turn. What’s happened over this last decade and a half in turn is evidence enough.

It’s worth noting in conclusion that during this same 24-hour period I’ve just been talking about, George Clinton is still doing his thing, though in a different context, with so many of the players from his past gone or withdrawn. Over at Glastonbury, he, Mary J. Blige and Grandmaster Flash all appeared in a joint performance of Mark Ronson’s ‘UpTown Funk!’. Ronson gave credit to Clinton for being there for the start of so much, and yet inevitably there was a feeling, again, of mediation lurking behind it all, of needing an outside voice to say a deeper truth. So seeing Clinton’s name trend anew on Twitter thanks to his own headlining performance the following night, leading yet another incarnation of P-Funk onto the stage and bringing liberation and silliness felt right, an acknowledgement through time of those deeper truths. And it felt like even the simplest but most direct of calls – that you can and should get off your ass and jam – loses none of its potency over four decades. Why should it? It never will. And the voices will continue, and the celebrations and the anguish and the sheer humanity, whether the names are Kendrick or Dawn, Kanye or Mykki, D’angelo or Brittany. Or Bree and Barack. And those with eyes will see, and those with ears shall hear.