In 1969 feminist Carol Hanisch wrote an essay called The Personal Is Political. It was her response to criticism that the ‘consciousness raising’ meetings she was organising were not political, but personal. The meetings were therapy, said the critics; navel-gazing at the expense of bringing down the system.

"They belittled us no end for trying to bring our so-called personal problems into the public arena – especially all those body issues like sex, appearance and abortion," Hanisch wrote. "I continue to go to these meetings because I have gotten a political understanding which all my reading, political discussions, political action and all my years in the movement never gave me… I am getting a gut understanding of everything."

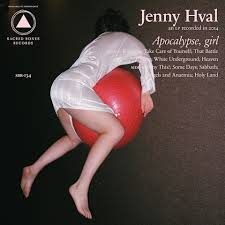

Forty-six years on, most women accept their gut understanding of "personal problems" does not distract feminism from the good fight, but takes it to where it needs to be fighting. Collectively, women are giving "all those body issues" the gravitas they warrant. Individually, disgorging the early force-feedings of patriarchy remains tough and lonely work. I fear I’ll die half-mended and I regret the head-start I wasted 20 years ago because I didn’t like riot grrl. Friends, film and books have informed my journey but rarely has music. That is until Norwegian musician Jenny Hval’s fifth album Apocalypse, Girl took me to a place I didn’t know music could reach into and unravel.

Hval is already established as a deep thinker, experimentalist and ruthlessly honest voice. Compared to 2013’s Innocence Is Kinky, Apocalypse, Girl is less noisy and more thematically united. Contributions from cellist Okkyung Lee, harpist Rhodri Davis and Swans’ Thor Harris are strong but subtle and there are few harsh effects or squalling guitars. But despite its minimalism, the record is "difficult". It’s as if Hval has recognised our grip on what constitutes confrontational music – volume, distortion, speed, repetition, abrasive textures or blank minimalism – has calcified so she has pried off our hands, laid us in Shavasana pose and turned our palms sky-wards to receive a new transmission. She prowls between lyrics, spoken word and associative poetry, entering a dream state in order to exorcise seminal moments, as on ‘Sabbath’: "I’m six or seven and dreaming that I’m a boy." Sometimes her voice is piercing and painfully expressive, sometimes it thickens in her throat with a smile and is unbearably intimate and all-knowing. Always it is uncontrolled and uncontrollable. There is bravery and risk in it.

"What is it to take care of yourself?" she asks on ‘Take Care Of Yourself’, spectral amid the eerie space of four ascending synthesiser notes. As the notes quicken to double time, she rephrases it: "What are we taking care of?" Unsung on paper it reads like a question from a self-help charlatan, but Hval keeps probing the platitude and questions keep spilling forth. Does taking care of yourself mean "Getting laid? Getting paid? Getting married? Getting pregnant?" or "fighting for visibility in your market?" Does it mean "not hurting yourself" or "shaving in all the right places"? Hval’s voice is tenderness incarnate, morphing into a hand to hold and support you. It’s not your fault if you don’t have the answers, the voice-hand says: it’s not your fault.

The album begins with the spoken word of ‘Kingsize’. Hval’s voice is remote yet hypnotic amid electro-acoustic clattering, distended groans and ambient washes. She references Laurie Anderson ("no big science") and Sex Pistols ("no future") and possibly even Sylvia Plath. "I search the oven, scrub the racks, put my whole head inside, but I just can’t find it. It’s like looking out the window in there." Ostensibly, ‘Kingsize’ is about America ("here I see no subculture") but in labouring to nail its point, you risk missing it entirely. Spoken word material has longevity precisely because it always feels too early to decode it. "The bananas rot slowly in my lap, silently, mildly, girly." Her words resonate but never resolve. They cast a shadow that moves like a cloud and I think of Bill Callahan’s ‘Jim Cain’: "Something too big to be seen was passing over and over me."

’Kingsize’ begins with a quote from Danish poet Mette Moestrup. "Think big, girl, like a king, think kingsize." Hval rises to the challenge, later singing on ‘Why This?’: "I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, I’m complex and intellectual." Actually, she is more. Her intellectualism is visceral – she embodies ideas and returns them to us raw, lived-in and relevant again. I’ve read a lot about women’s choices and conflicts yet never felt the shock of recognition I felt on first hearing ‘That Battle Is Over’, on which Hval sings in a kind of psychic scat "Statistics and newspapers tell me I am unhappy and dying" and of over-stimulus generally: "That I need man and child to fulfill me / That I’m more likely to get breast cancer. And it’s biology, it’s my own fault, it’s divine punishment of the unruly."

There are lots of cocks and cunts on this record: Hval’s own and those in "a million bedrooms". Elsewhere, bananas are cradled in laps and Hval longs to hold a man’s flaccid dick. These key words may lead people to think Apocalypse, Girl is about fucking. Because what do cocks and cunts do together if not fuck? How else do they exist in a single sentence, a shared bed, or in a paradigm of longing? But answers to these questions are what Hval is seeking. Her songs are not about sex but about how to transcend it as our idea of the ultimate connection. "Could I be that for you? That cupping hand on your soft dick? Could I give you that, that which sometimes expects nothing?" She yearns not for what we already know (not just women: all of us) but for a way to crack apart our confinements: our bodies, how we relate, the gender we’re born with, how we access god and find something bigger. Something kingsize.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/18042-jenny-hval-apocalypse-girl-review” data-width="550">