I want to know where the hollyhocks come from, she said, how they can burst from the asphalt like that, and why grapes can grow along the white limestone walls here, but not oranges, not even lemons as sour as they are, and the cold, why is it relative, people always say that, that it has something to do with the wind and the damp getting into your bones being worse than frost on your eyelashes, she said. Because I don’t think so, she said, I think flat landscapes are the most beautiful, along with dry topsoil, scorched earth, and I want to travel south south south as far as you can go, where you can feel the heat against the backs of your thighs when the sun is behind you and where you can sit on upturned boats during sunrise and you think that it will never be this beautiful again, you know? But of course I didn’t know, because the most beautiful things haven’t happened to me yet, I always imagine them to be in the future, we are different people in that way, she and I, and I have never seen the Adriatic or the dry earth, just big cities, taxis, clouds of smoke through which beautiful, willing faces emerge and through which greedy hands shoot out, impossible to defend yourself against. Her hands didn’t come from the dark of a nightclub, they came through a rosehip hedge, torn up palms, with dirt under her chipped fingernails, her eyes sought my gaze through the foliage, her southern Swedish Rs trilled between the twigs and her rough hair smelled faintly of seaweed and salt water.

(© Amanda Svensson. Translation © Saskia Vogel. Published by Readux Books, Berlin. Original Swedish text published by Novellix, Stockholm)

This month I read a book in translation every day for a fortnight. It might sound impressive/obsessive, but – as Berlin-based publisher Readux brings out single or groups of very short stories and essays, mostly in translation from German, French and Swedish in pocket-sized books that can be read in one sitting – it was close to effortless.

When founder and publisher Amanda DeMarco started planning Readux she was twenty-six and funding the project herself, so publishing four short books (of around 5-10,000 words) three times a year rather than full-length books was a ‘no-brainer’, though she actually regards Readux as ‘a magazine – incognito, exploded’.

Instead of telling you about all of the books – from Felicitas Hoppe’s absurdist nightmares, to Roger Caillois’ surrealist piece of psychogeography, to the revelatory story of a British poet becoming pen pals with an incarcerated Czech poet – I wanted to focus on Readux’s Swedish Series: not just because their short-form mini-book format is based on the Swedish publisher Novellix, who published the stories in Swedish, but because the three stories in this set were translated by the same person. They just so happened to also be the translator of another text that had recently made a real impression on me.

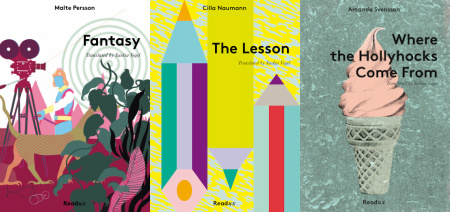

The trio of short stories that make up the Swedish Series was selected and translated by Saskia Vogel. Amanda Svensson’s Where the Hollyhocks Come From (excerpted above) was the first Readux book I read, drawing me in with the strangely menacing pink ice-cream on its cover.

It charts a young man’s melancholy liaisons with a Lolita-like girl in the countryside of southern Sweden and comes to a quietly traumatic conclusion. The story’s pull and that the girl’s looping speech snaps together so satisfyingly with the man’s preoccupied narration left behind the sense that this was translation at its best.

The narrator of Malte Persson’s Fantasy is a self-absorbed artist who infiltrates the team behind a failed fantasy film in an attempt to make a piece about their egotistical existences detached from real life; at times recognising her own hypocritical denial of how close she is to her subjects, her own self-importance and who’s using who. In The Lesson by Cilla Naumann, the most tense and ambiguous of the stories, a teacher’s inexplicable hate for a new pupil causes his control to slowly slip and has the threat of violence permanently hovering on the horizon.

I had come across Saskia a few weeks before when I read her translation of this excerpt from Pojkarna or The Boys by Jessica Schiefauer on the great platform Words Without Borders, and was left with a mournful wish that I had had the chance to read it when I was younger. The extract left a mark and the text itself was popping and as lively as the young girls in the story. Then I read the Swedish series and recognised Saskia’s name; this recognition felt like something to celebrate.

Literary translation is all too rarely considered an art, rather something more like an administrative task. It is part science, part mystery. It is engaged and impressive creative writing in its own right, and hopefully one day that will go without saying. Until then, I want to refract this idea through the prism of Saskia Vogel.

Saskia learned Swedish in her early teens when she moved from Los Angeles to Gothenburg to attend high school and went on to study English and film, followed by Masters degrees in creative writing and comparative literature in both the UK and the US. Her first editorial job was at AVN, a publisher’s weekly for the adult entertainment industry, but wanting to return to literature she found a job at Granta magazine in London, running their global events, PR and promotions. Now based in Berlin, she translates Swedish literature, is a writer in her own right, and is the co-founder and director of strategic communications at Dialogue Berlin.

Starting out in literary translation often happens by chance, was it that way for you?

Saskia Vogel: In a way, yes. While I was at Granta, Johanna Haegerstrom, the editor of Swedish Granta, sent a few stories along from one of their issues. One of them was about a strange bus journey to the Alhambra in oppressive heat by Lina Wolff (who And Other Stories is publishing later this year). It felt perfect for the travel issue that we were planning. It’s funny, at the time I was thinking about something Tina Fey said about saying yes to experiences even if you don’t feel ready for them, and a friend had been encouraging me to start sending my writing out, so putting myself out there and trying something new was on my mind.

John Freeman, the editor, agreed to let me have a go at translating the story and they accepted it for publication. I loved the process and felt encouraged by the feedback I got from him and the managing editor Ellah Allfrey and it made me want to pursue translation.

How did you come to edit and translate the Swedish Series for Readux?

SV: Amanda DeMarco had contacted me while she was setting up Readux to talk about the concept and strategy. Amanda needed a Swedish reader and asked me if I’d help select the stories from those published by Novellix and it went from there. After the Granta story, I had the hopeful-anxious feeling that comes with wondering if and when the next project will come along, and this one was so timely and perfect.

How do you prefer to work, what’s your process?

SV: I work in drafts. One bash it out draft to get it all down, and then a couple of drafts reading against the original text, a draft for grammar, voice… I do a draft for each read. I took the approach from a handout called ‘The Levels of Edit’ that I was given by one of the most incredible teacher’s I’ve known, Shirley Thomas, a professor and author who wrote films for NASA and who authored the Men in Space book series in the 1960s.

She was one of the people who made me feel like a career in storytelling was possible. I keep her approach to technical writing in mind whenever I work with text. She wrote: “In the wondrous world of tomorrow, where we all will be speeding along the information Superhighway, and like spiders we will be climbing the World Wide Web, the capability that can prove most stabilizing is that of technical writing. This is a talent diligently acquired, infinitely useful in any form of communication, and valuable to any application.”

How did you negotiate the editing process with Amanda without her being able to read the Swedish original?

SV: Unless I’ve been working on a sample extract for a Swedish publisher, I haven’t yet worked with an editor who speaks Swedish. I suppose it goes back to the levels of edit: getting the text into the best place possible, consulting the author if possible, and then going through a normal editorial process with Amanda. I’m struck by what an exercise in trust the process of translation is. The trust the author puts in me; the responsibility I have to them to handle their text with care, and the trust the publisher has in me, the trust that I’m not going to twist the author’s words for whatever reason or bowdlerize the text.

And did you work closely with the writers themselves?

SV: Oh yeah. Some of the best moments while translating occur when I get to talk about the text with a writer: circling a word to pin down the author’s intent and its exact nuance and meaning. There’s so much room for surprise and deepening in the reading. I love the dialogue that happens in the margins.

Each story holds a particular tension, and all of them deal in some way with sexual power. What made you choose these stories, these writers?

SV: Their emotional intensity and boldness. Naumann’s evocation of the oppressive smells of school and adolescent bodies and how she handles disgust slays me—the way Malte Persson layers nerd-dom, deception and perception with his unreliable, narcissistic, irresistible narrator—how Amanda Svensson’s style enhances the push and pull of young lust and aversion.

My interests tend to be around power dynamics and sexuality, Amanda Svensson’s treatment of these themes is dark and playful. She invokes my favorite pirate Anne Bonny in her latest novel. Her story perhaps aligns most closely with my own work, but really, the same could be said about the Naumann—that Oleanna-like power struggle between teacher and student—or the extremely tantalising exploration of fact, fiction and desire in Persson’s story.

So the themes in the books relate significantly to your own writing?

SV: I’m currently writing a novel that explores transactional relationships and who gets what out of them. At one point I realised that most women I knew had at some point engaged in sex work, usually kink-based. I also became fascinated with the kinds of social transactions I was observing and engaging in in Los Angeles. In the novel a young woman who is broke and failing at her acting career slides into casual dominatrix work. It’s a journey through the underbelly of Los Angeles that plays with the tradition of ‘stories of becoming’ that are often written about prostitutes, for instance Josephine Mutzenbacher, to keep on the theme of books in translation.

Would it be right to assume that your ‘other role’ as a literary translator informs your own writing process or ambitions in some ways?

SV: Translation certainly took some of the fear out of the process of writing. After I finished my first book-length translation, Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner? by Katrine Marçal, I had an aha moment. It feels embarrassing to share, but I thought: Wait, you mean a book is just a collection of ideas built around a narrative explored chapter by chapter? A scene is a finite thing? It only has to be 50,000-ish words? No problem.

When you’re a reader, a text can endlessly expand in your mind, that after-life of a book. I’ve just finished Miranda July’s new novel and I find myself muttering the name of one of the characters Kubelko Bondy like an incantation as the scenes and characters are freshly drifting through my mind. I think I had been overwhelmed by the magnitude of what books mean to me. Translation gives me perspective and reminds me that writing is a human act. It’s a privilege to get to sit with another person’s work, to think about their choices, style, meaning so deeply. And it helps me with the decisions I make on the page.

One of the stories in Anna-Karin Palm’s collection Hunting Trophies comes to mind; it had me short of breath from the start. A Stockholm woman finds love while on holiday in the Swedish countryside, there’s epic nature and the creeping feeling that she’s his prey. Terrifying and understated, quietly violent. I can only hope to be able to write with such elegant menace.

You also produce great events that seem far more considered and interdisciplinary – and far less stale and token – than many literary events, what do you aim for?

SV: I love producing events: the energy of people in a room making memories together. I was reading an Art of Fiction interview with James Ellroy recently and he was talking about how he was preparing for readings. I think his reply is my motto: “Never go long. Never try the audience’s patience.” He goes on: “How many times have you seen people go for forty minutes, lose it routinely, wet the page, cough, fart, belch into the microphone, say “um,” and do everything short of take a shit on stage. It’s deadening.”

I co-produce a quarterly event at the Ace Hotel Shoreditch with Michael Salu called Local Transport. We curate to a theme and each event is presented in three acts, one performer per act, fifteen minutes each. It brings together groups of people that wouldn’t normally be at a book event or an art event and mixes them all up. It’s in this shadowy basement with a long bar and candle-lit nooks, plastered with black and white pictures of Grace Jones. We make space for the writers to play with how they present their work. At the last one, Zoe Pilger read from her forthcoming novel and had this slideshow of images that showcased her sharp wit and themes in a wild way.

Coming back to translation: it’s obviously difficult to talk about ‘trends’ in a particular language’s literature, but what have you found in Swedish literature that has most affected and excited you?

SV: Did you ever come across Sassy magazine? It’s a teen magazine that was started by Jane Pratt. It was an oasis of female empowerment and quirky cool in a sea of bubble-gum teen mags. When I was in high school in Sweden, I kept finding books, magazines and movies that reminded me of that Sassy ethos and I kept meeting girls who knew what they wanted, were politically active and inhabited being female in ways that I hadn’t experienced as a young girl in Los Angeles. I’ve come to understand this as something that is characteristic of how gender is shaped by the country’s political legacy: an egalitarian starting point and a society that is politically engaged and deeply interested in world affairs. Of course, it’s not a perfect place and I’m finding my own statement problematic.

Jessica Schiefauer’s The Boys, that I translated an extract from, is one of my favorite Swedish young adult books. It addresses sexual harassment in schools and the objectification of teenage girls, and Schiefauer’s sparse and poetic language conveys the magic of the world she’s created so beautifully. It says such important things about the power of the gaze and the importance of having a space, a room of your own.

Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy also addresses the failure of the system to protect the vulnerable. I’d like to read more literary novels from Sweden addressing this tension between the ambitions of the society and its failures. I can’t wait to read more novels that explore multicultural Sweden. I’m thinking of Johannes Anyuru and Jonas Hassan Khemiri, among others, but those two can be read in English. There have also been a number of great short story collections that have been coming out by Oline Stig, Lina Wolff and Jerker Virdborg, and I recently came across a publisher called Rosenlarv, which could be compared to Persephone Books. They’re publishing forgotten feminist classics.

Do you think there’s more interest in literature in translation and understanding of what literary translators do?

SV: I’ve only been doing it a little over a year, so I don’t yet have a long view. It feels like yes. The literary translation community is close-knit, active, engaged, and vocal. I’m so impressed by translation-focused publishers who are working at addressing the relative lack of translated works and who are also simply publishing great books and stories. They’re engaging in cultural activism at its best.

I often think about Joan Didion and the statement “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Perhaps too often. I’ve been having an obsessive thought-cycle about how we make sense of the world through narrative and the danger of letting our narratives harden. What happens when we stop being open to allowing the stories we tell about ourselves and the world to be adapted upon in order to make new experiences or to receiving new information? We need stories from all over the world and from diverse realms of experience so we can understand the world we live in and so we can live and act with greater compassion. And then there’s the simple pleasure of arm-chair adventures.

What have you been working on recently?

SV: I’m finishing up a novel called Rarely Ever Fine that’s getting published by Frisch & Co. later this year by an Eritrean-Swedish author called Sami Said, which takes a fresh look at the conversation around immigration, Islam and the West through the eyes of an oddball protagonist. It’s earnestly funny. And then there’s All Monsters Must Die: An Excursion to North Korea by Magnus Bärtås and Fredrik Ekman. It’s reportage on North Korea about the kidnapping of South Korea’s most famous film couple. The authors layer a personal visit to North Korea, the history of Godzilla and that of the film couple, as well as the contemporary history and culture in Japan and the Koreas. It’s a brilliant, gonzo interrogation of a complex landscape. House of Anansi is publishing it in April.

What should we being reading from Swedish right now, translated or otherwise?

SV: Not because I translated it, but because it was the education in economics I’ve always wanted: Katrine Marçal’s Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner?, published by Portobello Books. It’s funny and illuminating: everything you need to know about why our economic systems aren’t working for us and what we can do about it. And definitely Ida Linde’s fantastic You Travel North To Die. It’s a “David Lynch goes to the North of Sweden and reimagines Bonnie and Clyde” kind of novel.

Finally: What makes a great piece of literature in translation?

SV: I suppose a great literary translation feels true. That is, the style, language, voice, and story are working in harmony. And it must take your breath away.

Readux Books is currently working on preparations for the second year of their New German Fiction contest and a series of erotic literature.

Saskia Vogel started working as a literary translator in 2013. She is the editor of Readux Books’ Swedish series. Her translations include Who Cooked Adam Smith’s Dinner? by Katrine Marçal (Portobello Books, out 5 March), All Monsters Must Die: An Excursion to North Korea (House of Anansi) by Magnus Bärtås and Fredrik Ekman, The Summer of Kim Novak by Håkan Nesser (World Editions), and Very Rarely Fine by Sami Said (Frisch & Co). She also writes fiction and has previously been published by The White Review. She holds an MA in Comparative Literature from University College London and a Master’s degree from the Professional Writing Program at the University of Southern California.

Jen Calleja is a writer, literary translator and musician based in London. Her short fiction, poetry, articles and reviews have been published by The Quietus, Structo, Huck and Modern Poetry in Translation, and she has translated prose and poetry from German for Bloomsbury, PEN International and the Goethe-Institut. She edits the Anglo-German arts journal Verfreundungseffekt. She plays in the bands Sauna Youth, Feature and Monotony.