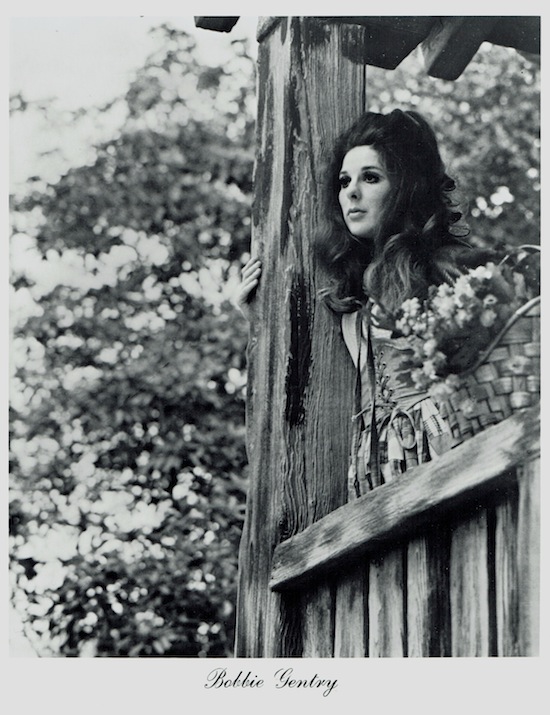

Never seen before picture of Bobbie Gentry performing in 1966 with band courtesy of Bryan Holley

Country music has always been home to strong women who made their names with feminist and protofeminist songs — think Kitty Wells’ ‘It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels’, Loretta Lynn’s ‘The Pill’ and much of Dolly Parton’s oeuvre. That tradition continues today with Maddie & Tae and Miranda Lambert recently serving up breakout hits that took on bro country and condemn domestic violence, respectively.

On the fringe of the collective memory of this complex tradition of feminism in the country music world, there’s Bobbie Gentry. Her first and biggest hit, ‘Ode To Billie Joe,’ tells the story of a young woman learning that her friend Billie Joe McAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge right after throwing something off of it. The mystery of Billie Joe’s tragic end captivated audiences around the world, but just as compelling is the tale of the tune itself — with it, Gentry became one of the first women in history to write, sell and, she insists, produce her own music. That she didn’t get the credit she deserved was a product of the times, but her journey opened new doors for women in country to take charge of their own work and image. Feminism indeed.

And then there’s ‘Fancy,’ the story of a young woman turned out by her mother as a last ditch effort to help her survive. In the end, the song’s protagonist thrives as a high class escort. In a 1974 interview with LGBTQ magazine After Dark, she calls the song her "strongest statement for women’s lib".

"’I agree wholeheartedly with that movement and all the serious issues that they stand for – equality, equal pay, day care centers, and abortion rights.’

"’But you look the epitomy of everything they dislike,’ I say, ‘you wear false eyelashes, vampy clothes, and you play up your femininity to the hilt. That can’t go down too well with those who picket beauty contests, burn Bunny dressing-rooms, and tell us to let our armpits grow out in all their glory.’

"’Well, that small group does more harm than good by drawing attention away from the real issues. Actually, I’ve had no problems with them, perhaps because they recognize the fact that I am a woman working for herself in a man’s field. After all, I am a successful woman record-producer. Did you know that I took ‘Ode to Billy Jo’ to Capitol, sold it, and produced the album myself? It wasn’t easy. It’s difficult when a woman is attractive; beauty is supposed to negate intelligence -which is ridiculous. Certainly there are no women executives and no producers to speak of in the record business. Mind you, inequities work both ways. For example, the divorce laws are rotten because they discriminate against men.’"

In Ode To Billie Joe, a new contribution to Bloomsbury’s 33 1/3 series, journalist Tara Murtha puts Gentry’s feminism and efforts to control her own image at the center of the work, which re-introduces the world to Bobbie Gentry. After she disappeared from public life in the early 80s, the public memory of Gentry has lost most of her contributions, which included years as a Vegas show runner, a stint as the first women to host her own BBC show, and numerous collaborations. Today, it is unclear where she lives and remains in touch with only a few friends from her days in show business — leaving many questions unanswered. ‘Ode To Billie Joe’ is a "looking glass that cuts both ways," Murtha writes. "The wild commercial success of ‘Ode’ transformed Gentry from an unknown working musician to an international star. But it also set a commercial precedent that proved almost impossible to repeat, and ultimately served to obscure a larger, richer body of work — and caged the artist into a persona she spent the rest of her career trying to transcend."

Bobbie Gentry spent most of her later career trying to become someone other than a Delta sweetheart to her audience, with mixed success. Why was Gentry’s effort to separate her real identity from her persona so important? In what ways did she succeed and fail?

Tara Murtha: Audiences underestimate female artists by assuming that everything they’re doing and writing about and singing are diary entries. To a large extent, it’s feminist to acknowledge that you created this artistic persona. There is no equivalent, no shorthand, for women doing that like there is for glam rock. Women aren’t supposed to do that, you’re crazy if you do that.

But look at Dolly Parton! She’s talked about the persona of Dolly Parton, that the real Dolly Parton is a ventriloquist, and the dolly we know is just that, a dolly. I think that’s really feminist for her to say, that it’s an amazing artistic creation. Bobbie Gentry was excited to explore the entire menagerie of characters she created in her head, and she got frustrated with people expecting her to just do that one character, which is why she went to Vegas, and why she had a huge cult gay following. Gay men really appreciated her over the top aesthetic, that she was an entertainer and not just the Priscilla Presley-haired country singer.

Who was Gentry, besides a legendary country singer? Why was it so complicated for her to break away from that singular identification?

TM: She was very interested in Latin jazz and hula; you can hear those rhythms in the work. Her material was the South and she was interested in the culture of the South, but it’s not necessarily country music per se. I’m not interested in convincing anyone out of that, but listening to the rest of her catalogue she moved further and further away from what she euphemistically called regional songs.

She really wanted to break into television because she found it a really dynamic medium, and being the music theatre geek she was, she designed costumes, she was interested in engineering and how all those production pieces fit together. She did a pilot of a show for CBS, and the producer was the producer of Hee Haw. They wanted her to do it a little bit more hillbilly and do humour, and she was funny, but even the reviews picked up that it was sanitized.

Part of Gentry’s story is that she didn’t always get credit where it was due — she was heavily involved in the direction of all her records but didn’t get producer credit until her final album, Patchwork.

TM: I think she left the record industry because she refused to compromise. That’s the last phrase she said in her last song on her last record, [‘Lookin’ In’] and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that was the first record she got full producer credit on. She went to Vegas and started performing on stage sort of like Zelda Fitzgerald. When you dance and do these amazing productions, it’s your body, and nobody can say you’re not doing it. With her writing, singing, and producing, men tried to take credit for it and no one else could see behind the scenes. It reminds me of something in that Pitchfork article about Bjork — having to pose in front of the equipment to prove she’s associated with it.

Gentry found huge success in the UK, in part because of her BBC show in the late 60s. What endeared her to the British audience?

TM: She had appeared on one of Stanley Dorfman’s shows and the audience reaction was so intense that they invited her back to host her own show. I was talking to a gentleman in London the other day about Bobbie Gentry. People in the UK really are interested in the rural imagery of American country music. Even now I have a ton of musician friends, Americana type artists, and they can’t make a living [in the U.S.], but they go to Germany and the UK and make a living making music inspired by Johnny Cash. They have an affinity to that type of music, and she had the exposure from the BBC show.

You started out asking, "Where is Bobbie Gentry?" but in the end your work was to find out who she is. Are you closer to the answer? What questions do you still have?

TM: Yes, I have a much better sense, I think, of understanding who Bobbie Gentry was. I say was, because who she is now is impossible to know without knowing her personally. Five years ago, I wasn’t even sure if I had ever heard ‘Ode To Billie Joe.’ When I started writing the book, I knew I was going to follow the thread of her 1974 claim that she produced ‘Ode To Billie Joe’, but had no idea what I would find. I was aware the Bobbiebilia existed, but hadn’t yet had the chance to look at its contents. What the Bobbiebilia – a collection of memorabilia stretching back to her early career, grade school report cards, correspondence – made clear is that she decided to become a success early on, and then trained for it like an athlete.

I’d like to know what happened to all of the projects she was working on that never came to fruition. I’d like to know if she really wrote songs under a pseudonym for other artists after retirement — there are rumors. I wonder what her relationship to her ‘Ode To Billie Joe’ persona was like then, and what it’s like now, or if it even exists at all. Though she was so brilliant at marketing and business, there was also a real desire for audience members to "get" her, for real. I’d love to know what she thinks about the same old issues about female entertainers – the assumption art is confessional, the accusation that you can’t be feminist if you’re performing femininity – almost 50 years after she dealt with that shit. I wonder what art she has been making all this time, and how seriously she has ever considered coming out of retirement. I wonder what she makes of this renaissance of interest in her work.

Most of all… [LAUGHS] I wonder what Billie Joe threw off the Tallahatchie Bridge.