"There is so little time for us all, I need to be able to say what I want quickly and to as many people as possible. Time passes so slowly if you are unaware of it and so quickly if you are aware of it." Marc Bolan, 1971.

Life’s a gas. I hope it’s gonna last.

After leaving it too long gathering dust, emasculated and needle-less, I finally rehooked my turntable up this year, dug big speakers out the attic, rifled through boxes clearing cobwebs, got back into the old routine, wiping, cueing, dropping the stylus on its magical journey up hill and dale. It’s changed my life again, like it did. The speakers are perhaps more magical than the medium, the way they’ve dragged my musical life away from the computer, the way they’ve stopped music being head-sized (or even worse, laptop-sized) and made it room-sized again, sometimes house-sized. The constraint of LPs has helped as well. You recall just how quickly 30-45 minutes can pass, how perfectly it fits the limits of your attention, or rather how affected by listening to albums your musical attention-span is, how in contrast to the dizzying endlessness of playlists and mixtapes the LP can lend a focus and weight to music not easily recreated by any other format.

Reconnecting my access to music to speakers and an amp and the all-important earth-wire, rather than headphones and a broadband connection, has made music warm again, in an engulfing way, bought back the memories that you associate with fond scratches, locked-grooves from spilled booze, drunken DJing, parties that got out of hand. Also memories of how these artefacts came your way, the penury and poverty and saving and joy of discovery, and also the things handed down, stumbled across, outright stolen. I remember my elder sister had a friend who’d frequently wear a coat whose entire lining had been transformed into a swag-receptacle. He came to ours once after a trip to Cov HMV in about 1983 and carefully lifted a record from his magnapocket. I held it in my hand and stared and stared and stared at the cover. Stared until its still image danced with light, trembled with possibility. From that moment, before I’d even heard a lick of the music, I was hooked helplessly. The record was T.Rex’s Electric Warrior.

The album is T.Rex’s most blazing statement of intent, a mark in the sand after the steady progress towards the full-band electric sound that the self-titled album of 1970 had hinted at. The single ‘Hot Love’ had finalised Marc Bolan’s Judas-moves towards popstardom in March 1971, stayed at Number 1 for six weeks, turned Bolan and T.Rex into teenyboppin’ stars. The wedge with the underground was firmly in – when T.Rex headlined the Weeley Festival just outside Clacton alongside the Faces and Status Quo in August ’71 they were booed onto the stage by the same hippies who’d previously loved them, who saw their electric manoeuvres as a betrayal, who were too slow and too dumb to follow the trails Bolan was blazing. It perhaps didn’t help that Bolan took to the stage and announced: "Hi, you might have seen me on Top Of The Pops. I’m a star." The bottles and cans started raining down and didn’t stop, although Bolan himself later on in the year said, "It really wasn’t a question of booing – I never heard any. There were a few loudmouths, one of which made a nasty remark and I replied in kind. But he made the same remarks to the Faces. A few flying bottles and a lot of noise – what usually goes down at a pop festival."

A world away in 1983 I didn’t know about any of that. Reference to Bolan in most rock literature at the time conformed to that lingering perception of Bolan as somewhat shameless, a chaser of mass appeal, like that’s a bad thing, like that shouldn’t be the point when it so clearly nearly always should. The books and pop encyclopedias that were pretty much all you had to go on in order to flesh out your listening had him down as a fad, a fly-by-night, a flash in the pan whose demise and disappearance were an inevitable result of his essential limitations, a flogger of dead horses, a safely neutered one-trick pony who died young and didn’t stay pretty. Bowie, Roxy – pioneers. Bolan? A cut above Mud perhaps but not by much. When my sister borrowed the record and I got to listen it was one of my first lessons in how deceitful and reductive and plain wrong the canon could be, how dependent on conservative ideas of auteurship and masculinity, how much it could prevent you from hearing if you took its constricted curatorship as gospel. ‘Mambo Sun’ rubbed in and my whole body and soul suddenly sang like a tuning fork rapped on a pylon, buzzing like a jacked circuit, a two-chord thunkafunk spiral you couldn’t and wouldn’t want to extricate yourself from. I started falling inexorably into Bolan’s step, stance and imagination. This was some of the most instantly, purely pleasurable sound I’d ever heard. And despite the move from duo to band, it’s the loosest Marc ever sounded, the rawest album, the one most exquisitely poised between freedom and finesse.

On one level, you can hear Electric Warrior as an attempt to win over America. It has a solidity of groove, a conciseness in the lyrics that’s new – it’s irresistibly an easy instant album to enjoy. But because Bolan’s songwriting never seemed to be making an effort to be liked or diluted, always at root expressed something natural and weird and beyond artifice, there are enough tracks on Electric Warrior that complicate the picture, that make it more than just a party record. Of course, ‘Get It On’ and ‘Jeepster’ still sound immense, still glide and surge and pirouette with a spark-heeled light-touch heaviosity unmatched by anyone. But it’s the side-tracks, the detours and derailments, that truly overwhelm you.

The murderous thump of ‘Planet Queen’, The almost-mathematical psyche-grind of ‘The Motivator’, ‘Life’s A Gas’ and its helium-filled spaces and silences. Visconti was truly finding a way to blend the acoustic, electric, symphonic and funky in ways that cleaved and fitted like a glove around Bolan’s musical abilities and limitations. Two tracks on ‘Electric Warrior’ will truly change your life, and if they’re not part of your life yet you need them in there as soon as possible. ‘Cosmic Dancer’ is so beautiful, so heartrending a song – if it was kept down to Bolan and his acoustic it would be stunning enough but with Visconti’s arrangement it actually makes your chest sob, your throat choke, your tears flow like the strings and drums that so acutely accentuate your heartache, makes you cry like a funeral. And the closing track ‘Rip Off’ is just mental: a boogie Curtis Mayfield or The Stooges would be proud of but stranger than either of them would conceive of, modernist like a Duchamp nude falling down a staircase, shot through with a blast of ancient drone-jazz in its coda that still fries your tiny mind, lyrically as savage and sharp as it is abstract and diseased.

And oh god it has always sounded so good on vinyl. As a fan I’d say all T.Rex albums are essentials but if I was pushing one at a neophyte as a gateway-drug it’d be EW. Once you’re hooked by it, and you will be, there’s no turning back, T.Rex and Bolan’s music will be a lifelong relationship for you. And like all relationships it’ll go through changes. I’ve already stated on The Quietus that EW’s follow-up, The Slider became my fave album, perhaps thanks to over-exposure to EW. I can now safely say that 1973’s Tanx has supplanted The Slider as my fave, perhaps again down to over-listening. That’s the thing with T.Rex. You do get greedy about it, pig out, binge. As a pop fan, as an innate model of how to make music so moreish you end up wide-eyed and slathering your gums with it and hitting rewind til dawn, Marc always made addictive music that you keep returning to. I suspect once I’ve worn out Tanx, Zinc Alloy will take its place, but penury and rarity has meant that Bolan’s later work, the albums that followed Zinc’s awesome hints towards a blacker, lusher, more ‘soul’-inflected sound, have so far passed me by. Reading interviews you get the feel that Bolan’s output around the time of 1975’s Bolan’s Zip Gun, especially in a recording sense, had become less focussed, as much of a mess as his coke-addled head. Recording became something to be fitted in around a chaotic tour schedule, ongoing label shenanigans and his suitcase-life led between his tax-exile home in Monaco and the biz he still felt part of in London.

By now, the music press hated Bolan, displaying a kick-him-when-he’s-down venom in their reviews that was almost gleeful, as if to counter what they condescendingly perceived as fawning coverage from the likes of Jackie and Cosmopolitan. The album was the first to only be released in the UK and it didn’t even crack the charts, unthinkable only a couple of years previously. It seemed the canon was proved correct in not considering Bolan’s later works ‘worthy’ of serious consideration, tagging them as desperation from a man whose time had passed. Always though, listening, you realise that what sustained Bolan creatively throughout his life was an energy that was unstoppable, that he couldn’t help acting on. Until he died he was surely one of our busiest ever popstars – think about how much he packed in, how rich that discography is from so few years. In 1975 he was telling Melody Maker exactly where he was going musically and not for the first time he found himself shadowed by former friend and rival, David Bowie.

"The Top 40 is very tiring, but I’ve been listening to a lot of soul stations. Black producers are just rediscovering the use of sound, like the rock & roll producers did after Sgt. Pepper. Bowie and I have the same influences, but it just comes out sounding different. In fact, when David and I got together a few weeks ago and suddenly totally related for the first time after ten years, we sat down and played records for each other. Amazingly we all had the same records – black soul records…"

Tony Visconti, so vital a part of Bolan’s work up until then, had left during the recording of Zinc Alloy, alienated by Bolan’s ballooning ego, drug problems and consequent unreliability. Visconti, perhaps more than anyone else, realised that Bolan’s was a unique talent best served by an amazing team, realised the importance of the ensemble behind the star. Consequently, without Visconti’s care and control Bolan’s Zip Gun immediately sounds different: in ’77 Bolan himself would admit to Paul Morley that, "I just really didn’t know where I wanted to go. Musically that period was really bad. I was getting really split up and things – looking back I was way off-beam. I didn’t want to play. In my head I was very upset. I’d get into the studio with all the songs and I didn’t want to play them. It was very strange. People had to put up with a lot of shit. I just didn’t want to play. I’d book the studios and then just sit around."

Which should make Bolan’s Zip Gun sound rushed, indulgent, unsettled, off-key. It’s all of those things, but that’s what makes it so fucking ace – whether it coalesces into a ‘statement’ is irrelevant when in parts it’s so entrancing. Reviewed as a rock album, as a ‘progression’, it barely hangs together, sounds like what it is: a series of outtakes/ideas splattered together in ramshackle fashion. Reviewed as a collection of grooves though, it’s absolutely smoking. Visconti’s disappearance perhaps means it suffers from a lack of cohesion but with Bolan’s increasing focus on the details of the beats, the frenetic precision and lubricated hydraulics of the rhythmic chassis, the songs veer between ultra-modern disco-funk and old-skool swinging blues in a way that recalls no one so much as mid-’70s James Brown (at the time, another star on the skids looking for a way to move on). Like with JB, Bolan’s lyrics had almost become a self-generating set of self-parodic clichés. Like with JB, that doesn’t matter when those clichés still work so well – the rip snorting ‘Light Of Love’, ‘Solid Baby’, ‘Space Boss’, the utterly unplaceable ‘Think Zinc’ and the Delfonics-New-York-Dolls crush-up ‘Till Dawn’ are as convincing and cherishable as Bolan’s finest work, and every other track contains at least a half-dozen moments of wonder you feel would’ve been acclaimed if the press and critics didn’t have it in for Bolan so heavily by then. As a fan you might have accepted the official line that this is Bolan’s worst album. Don’t. It’s a corker. He didn’t make a worst album. Just albums that were slightly less awesome than others.

1976’s Futuristic Dragon needs no apologies at all. (Paul Morley forced apologies out of Marc in ’77 – "Yeah, that was bad" – but fuck that, Morley corners him, forces it out of him by slagging the album off to his face. Folk were so keen to be seen as mean to Bolan). Your first tip-off that a fresh impetus, a recovery of boldness is afoot is the sleeve, designed by George Underwood who’d first worked with Bolan on the first Tyrannosaurus Rex album, 1968’s My People Were Fair And Had Sky In Their Hair… But Now They’re Content To Wear Stars On their Brows. There’s a reconnection with that older period in the music too, as if stung by Zip Gun‘s commercial failure Marc had got back into the entirely isolated Spector-obsessed musical oddness of his early pre-band work. It’s perhaps the most studio-bound and confected of all Bolan’s post-Visconti albums, slathered in effects and painstaking ornamentation, widescreen, gratuitous, excessive, sublime.

The opening on ‘Introduction’ is just fucking nuts – a billion guitar solos at once rippling over a Funkadelic-style synth-laden groove over which Bolan sets out his new stall of lunacy: "Relentless dimensions of quadraphonic sleep/Dwelt the wild grinning cyclopean pagan/Screaming destruction in sheer dazzling raiment…" This is not the sound of a man in retreat, rather the sound of a man who has used music to fend off darkness finally surrendering to that darkness and exploring his own imagination with the freedom of someone liberated from commercial concern or restraint. (And, as is so often the case, that freedom and ease actually brought back some of the commercial success that had been waning – ‘Dreamy Lady’ became a hit even before the rest of the album was complete and its follow-up, the insanely catchy ‘New York City’, returned Bolan to the British Top 20.) Second track ‘Jupiter Liar’ is classic Bolan, a melody only he could write, guitars startlingly modern in their fuzzed-out atonality, a song you couldn’t imagine anyone else dreaming up. ‘Chrome Sitar’, the stunning cine-funk glide of ‘Calling All Destroyers’, the thrilling stomp of ‘Sensation Boulevard’ and the mindbending closing double-shot of ‘Dawn Storm/Casual Agent’ see Bolan’s lyrical eye widening, his voice glorying in its own still-simmering sexuality and shimmering grace and also reveal just how subtle, multifaceted and fearless Bolan was as a producer, with sounds conjured from words and words conjured from sounds in a way clearly learned from Visconti. Futuristic Dragon isn’t just a conventional return to form, it’s a totally new trajectory and a vindication of Bolan’s undimming self-belief, and it needs serious reappraisal as up there with Bolan’s greatest albums, certainly a match, if not better than anything Roxy, Bowie or Sparks were putting out in 1976. You get the sense of a man starting to get disciplined again, refocusing his energies ready for coming fights, the brewing storm, a future.

"The new band is helping. I’ve changed my whole approach. I’m gonna make sure I know exactly where I am. It’s been amazing. All my old enthusiasm is back. We’re all having great fun and wanna play together as long as possible. No Gloria; all men. New material, very little golden-oldie stuff, and those done tight, not sprawled. I don’t drink at all now. Not for two months. I don’t drink, I don’t smoke, I don’t take drugs. I screw a lot. I want to do a Marc Bolan album, but I don’t know what it is yet. It’s gonna be like nothing I’ve ever done before. Might be a spoken-word album, it might just be me cracking eggs with loads of echo…" Marc Bolan, 1977.

In summer 1976, after the release of Futuristic Dragon, ‘I Love To Boogie’ had given Marc his biggest hit in years, hitting Number 13 and staying in the Top 20 for nine weeks (and also, because of its similarity to Webb Pierce’s 1956 hit ‘Teenage Boogie’, prompting rockabillies to attempt a staged burning of the single at an event held in a pub on the Old Kent Road). By the time 1977 rolled around Marc was starting to smell vindication. Punks only needed three chords. That was all Bolan ever taught them, frequently he needed less, Bolan started checking out London’s nascent punk scene in late ’76 and feeding off its energy. He soon started speaking up and showing out in support of bands who, though they might have only avowed a love of Bowie and The Velvets in public, had doubtless all been massively affected by Bolan’s early-’70s run of wonder as well. Bolan was pictured in early 1977 hanging with the Ramones, and after putting together a new band in late 1976 (when the last remaining member of T.Rex, Steve Currie, left for good) toured in spring 1977 with The Damned, billed as "two-and-a-half hours of punk funk".

Dandy In The Underworld features a couple of tracks by the old T.Rex line-up (including ‘I Love To Boogie’) but it’s dominated by the new cast of players Bolan had assembled, including Herbie Flowers and Tony Newman. This was the band introduced to the public most visibly on the Marc TV show that Granada commissioned in early 1977 – inconceivable in the years beforehand not only because of Bolan’s fading fame but his spiralling cocaine addiction. Cleaned up, surrounded by fresh heads, the Bolan you see on Marc is someone utterly reconnected with music and finding a new joy in playing live, in dispensing with repertoire he couldn’t summon fake interest in anymore. The album, after its launch at punk stronghold The Roxy, got the best reviews any T.Rex album had received in over half a decade. The previously fiercely hostile press was unable to resist its soul-revue confidence, its new connection with a new underground. That connection is partly down to perception, partly down to the genuine revitalisation you can hear in the songs, but the music is still exploring Marc’s soul-obsession, still shot through with Marc’s constant lyrical themes, how to use imagination in the interests of survival. Some of the deranged complexity of Futuristic Dragon is shorn away; these are tight little soul-pop songs, stripped back, simple in instrumentation even when complex in tempo and arrangement (the churning ‘Visions Of Domino’, unforgettable ‘Soul Of My Suit’ and drama-driven ‘Jason B. Sad’). ‘Teen Riot Structure’ closes ‘Dandy’ out on a unique blend that points towards what the next album might’ve sounded like – pure Bolanesque chords but played like the Ramones, the lyrics haunted with foreboding of coming fires and catastrophes, "ankle deep in fear… all London was in blazes burning to the sound of deep galactic tragedies in stereophonic sound."

The last line Bolan ever sang on an album is, "The teens held hands on shifting sands and wonder what they learn." By the time Dandy came out, Bolan was already planning his next move, singing, "Hey little punk forget all that junk/ Summer is heaven in ’77" on the fab ‘Celebrate Summer’ single (that together with all the singles that were left out from the albums, including essentials like ‘Children Of The Revolution’, ‘Solid Gold Easy Action’, ’20th Century Boy’ and ‘The Groover’, is included on the two bonus discs here, alongside rarities with Gloria Jones and assorted studio-doodles). A month after ‘Celebrate Summer’ came out, Marc was dead. Inevitably then, in retrospect, Marc’s passing renders Dandy full of promise and full of foreboding. In truth it feels like a transitional record, a stepping stone to something truly wondrous to come, something Dandy tantalisingly hints at.

Something we’ll never hear.

It’s so difficult listening to Dandy In The Underworld knowing it will be Bolan’s last blast. For me, Bolan’s death in 1977 is just about the most upsetting rock bereavement of all time, right next to Jimi. Not just because of the horrible random tragedy of the nature of his death, but because like Jimi, you get the sense that here was a man who had so much more to offer, so much more to give. Just as it’s heartbreaking thinking of what Jimi might have done in the 1970s (especially as you feel he would’ve got further into the funk and jazz he was exploring with Buddy Miles and Band Of Gypsies), you feel robbed of the wonder that would surely have been Marc Bolan in the late ’70s and early ’80s, when so much of what was going on in UK pop was so clearly made by his devotees, when he finally started getting taken seriously as one of British pop music’s most important figures, someone who never failed to deluge his listeners with delight and intrigue.

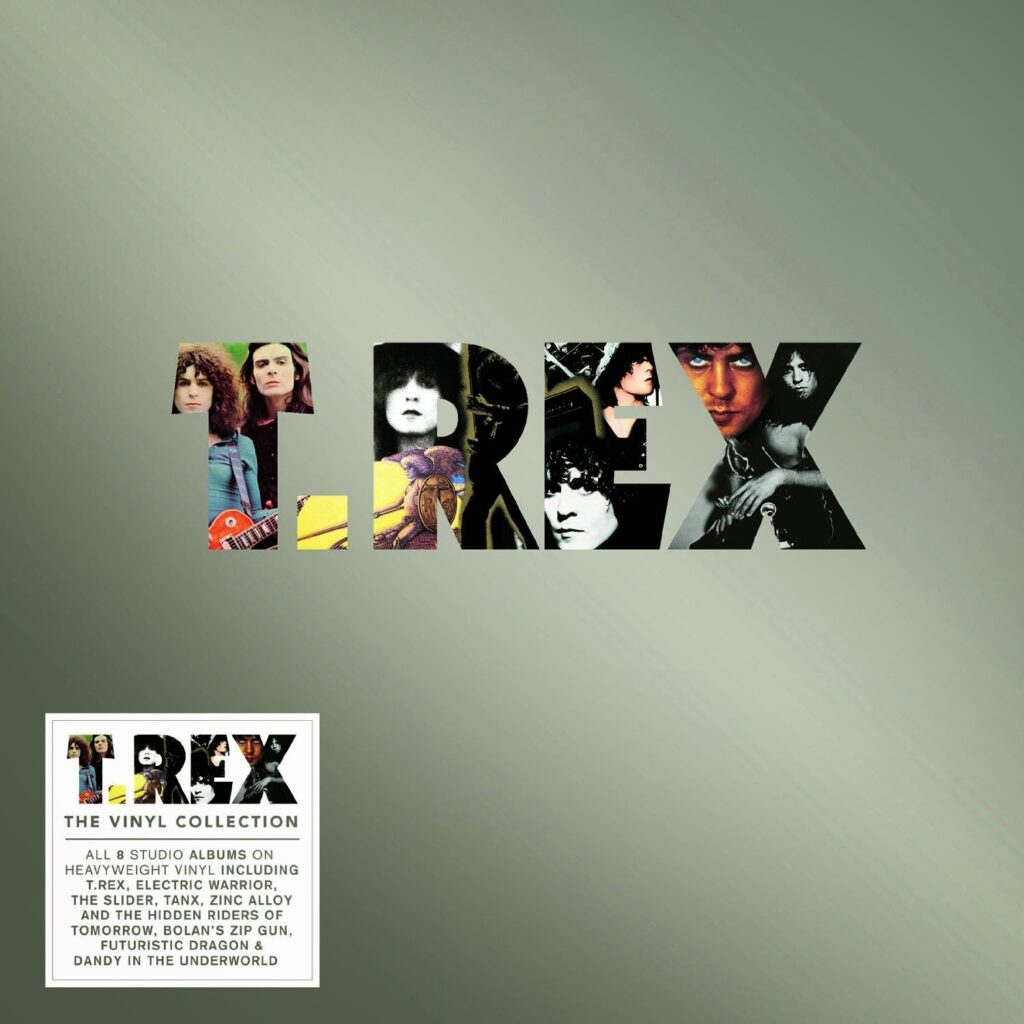

You wonder what he’d have done with the changing technology, with the resurgence in his stardom that would surely have come. You suspect of course that he might have fucked it all up again but more strongly you suspect that he wouldn’t have this time, that even if it meant settling into the cycle of reunion tours and chatting with Gloria Hunniford on the Pebble Mill sofa he still would’ve been a part of our national pop life and crucially would’ve been happy. I was five when Bolan died, but I cling to the fact that me and him lived on Earth at the same time at one point, that the air he breathed was the same that found its way into my infant lungs, that I once lived in a world where Marc Bolan was a living popstar, moving through time, walking down streets, dreaming his dreams, touching, with pleasure, his inner depths, flashing with pleasure, his smile, his style, his outer beauty, that smile, that sweet laugh that gets in your soul. This box is all the T.Rex you need and one of the greatest bodies of work anyone involved in British pop has ever given us. With Marc on the deck, spinning, back in the air you breathe, life’s a gas.

I know he’s gonna last.