"My grandmother knew the junk man and after a brief conversation with him he directed his two sons to bring an ancient and well-used upright piano into our front room and push it up against the wall. I was seven years old. Old enough to start learning to play. What she had in mind was that I learn some hymns I’d be able to play for her sewing circle meetings. That’s how my music playing started."

(Gil Scott-Heron, The Last Holiday)

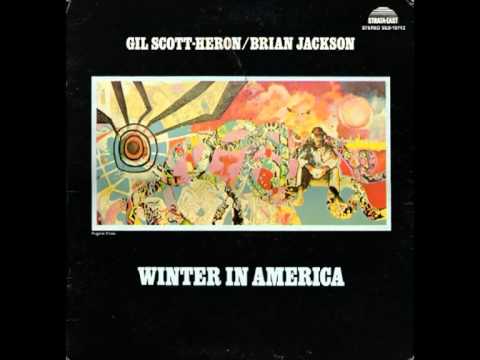

The music from black America in the 1970s has had its way with me a thousand times by now. I’ve celebrated with Kool & the Gang, and tripped with Funkadelic; danced with The J.B.’s and grooved with Donna Summer; I’ve wept with Donny Hathaway and Marvin Gaye. And I’ve lamented with Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson, pining for a better tomorrow throughout the utterly beautiful melancholy of Winter In America. Many of these borrowed memories of America in the mid-20th century remain simply just that, ageing and fading more and more each year. Yet despite its obsession with its present (now the past), and apparent focus on African-America’s plight, Winter In America is at its core a thematically all-embracing record, as cold and comforting as winter itself always is and was, whoever you are. These nine love songs for humanity reach a very special, and still mostly uncharted place in emotional music space, with Scott-Heron’s poetry given the most befitting possible stage on which to play out by Jackson’s wistful jazzy arrangements.

Gil Scott-Heron’s contribution to the world is seen more often than not as a mere stepping stone in the origins of rap. I say ‘mere’, only as there’s so much more to it than that, and to call the likes of Pieces Of A Man or Winter In America stepping stones towards Fear Of A Black Planet is to misunderstand an irrepressibly soulful meeting of jazz songwriting and witty poetry. Scott-Heron’s debut solo recording – a truly right-on album that saw spoken word poetry explore newly rhythmic territory atop congas and hand percussion – arrived the same year that saw The Last Poets and (former Last Poet) Kain drop their similar (albeit weirder and more theatrical) debut LPs of what would be later identified as ‘proto-rap’. Scott-Heron knew The Last Poets through the cousin of founding member, Abiodun Oyewole, who also studied at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania at the end of the 60s. It’s even been suggested that he once asked The Last Poets outright if he could "start a group like you guys?", although it seems a debatable legend, as Scott-Heron writes of The Last Poets in his memoir: "They were bringing a new sound to poetry and to the community… Their things were a cappella without music. I always had a band, so it was a different sort of thing. But we were trying to go in the same direction."

The main point being, Scott-Heron was more songwriter than poet, and more singer than rapper.

While The Last Poets achieved notoriety on the soundtrack to Cammell & Roeg’s seminal film Performance featuring Mick Jagger, Gil Scott-Heron’s Small Talk At 125th And Lenox, garnered breakout success via airplay on radio stations in Philadelphia, Washington, L.A. and the Bay Area. Fuelled by the success, Flying Dutchman Records head Bob Thiele gave Gil further studio time, and went on to hook him up with some stellar session musicians for the follow-up, Pieces Of A Man – including legendary bassist Ron Carter, and Bernard Purdie (a drummer so versatile that he’d already recorded with both Aretha Franklin and Albert Ayler by this point), with Gil bringing along Brian Jackson, with whom he’d played back at Lincoln in a band called Black & Blues. They revised his most raging poem from Small Talk – ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’ – with Scott-Heron’s razor-sharp tongue spewing black nationalist agitprop atop Carter and Purdie’s stomping bassy groove, and sounding every bit the archetypal proto-rap song. You almost expect Flavor Flav to chime in any second. The rest of Pieces Of A Man however, is almost poppy and never nearly as grating, and Scott-Heron himself would perhaps never again reach quite such dizzyingly angry heights as those on ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’. In addition to Scott-Heron’s temper, jazz’s far-reaching experimentalism was subsiding at the time, weary from the leaps into weirdness of Miles’ new thing and the proliferation of Ornette and Coltrane’s free jazz by the turn of the decade. Musically, Pieces Of A Man and its follow up, Free Will, are saccharine perhaps far beyond the requirements of Scott-Heron’s songs, with only Ron Carter’s bass playing perhaps pushing the group out of their comfort zone for deeper, darker highlights like ‘Revolution’ or ‘The Prisoner’. On the latter, Carter bows his bass like he’s kicking off some Pharoah Sanders epic, and pushes Brian Jackson – at that time, Scott-Heron’s silent partner and songwriting partner – to let out some truly spellbinding and out-there piano playing beyond anything else on the record. For the most part though, it’s sugar-coated jazz-pop, although the power of Gil Scott-Heron’s songwriting shines through regardless. The pair then changed label from Flying Dutchman to the more politicised Strata-East (whose roster actually included Pharoah Sanders), a label with a passionate desire for artist-centricity that put Scott-Heron and Jackson well and truly in the driver’s seat. As fate would have it, just in time to capture the pared down opus that is Winter In America.

Strata-East’s focus meant the pair – with Jackson now promoted from vital session player and co-songwriter to credited co-artist – recorded largely unassisted at the tiny D&B Sound studio in Silver Spring, Maryland. According to Scott-Heron, "the main room was so small that when Brian and I did tunes together, one of us had to go out in the hallway where the water cooler was located". And it’s a befitting setup, as Winter In America is about as intimate as music gets. Here at its very gentlest and silkiest, Scott-Heron’s warm baritone is whispering right in your ear, while the endless washes of Fender Rhodes and piano keystrokes raining down from Brian Jackson caress and hypnotise you. (As a side note, they’d only just been able to actually muster the funds to purchase a real Rhodes, something the pair had been quite rightly in love with since hearing Herbie Hancock play it on Miles In The Sky some five years earlier, so it’s no wonder the instrument is used on almost every track on Winter.) The album was supposedly mostly tracked and ready to go minus bass and percussion, with the sparse rhythm section added only on the final day, lending several tracks an up-close, demo-like quality with only voice, keys and some occasional flute courtesy of Jackson (who’d quite miraculously only recently taken up the instrument).

Sparsity and spareness are paramount throughout Winter In America, and the fiercely wordy, trigger-happy wit of Gil Scott-Heron remains relatively tame, and yet most definitely at its most intensely powerful. ‘Rivers Of My Fathers’ contains a lengthy instrumental introductory passage, with Brian Jackson spewing a pensive understated jazzy piano solo for some two minutes before Scott-Heron’s reflective vocals even start up. That ‘Rivers Of My Fathers’ is almost triple the length of ‘Revolution’, at eight-and-a-half minutes, and yet contains far fewer words, only some hundred-and-fifty, is perhaps reflective of Scott-Heron being knee deep in the economics of language, working as an instructor in the English department at Washington’s Federal City College: "I think I was a better songwriter when I was teaching writing," he writes. "When you work on songs, you have to tell stories in a limited number of words, just a few lines. You have to be economical. And when most people talk about good writing, they talk about economy."

‘Rivers’ lilting keys and gentle rim-shot rhythm, drenched in spring reverb and squelching away somewhere way back in your subconscious, coalesce with Gil’s simple words to create a dreamy dramaturgical fantasy, through that smoky late-night looking glass. "Looking for a way/ Out of this confusion/ I’m looking for a sign/ Carry me home." Scott-Heron’s words and Jackson’s music chase one another in circles, avoiding any full cadence, shimmering across a late night riverside moment frozen in time like moonlight over the bayou. "Let me lay down by a stream/ And let me be miles from everything/ Rivers of my fathers/ Can you carry me home." Throughout much of Winter In America, the Afrocentricity of the songs is less overtly pronounced than previously – ‘H²Ogate Blues’, for example, addresses America as a heterogeneous multi-ethnic whole – but the closing moment of ‘Rivers’ sees Scott-Heron climactically whisper revealingly, "carry me home… Africa". Before abolition, runaway slaves would follow rivers seeking to wander back to the sea, back up the rivers that brought their fathers inland, back to Africa.

The album quite pointedly spends a lot of time wandering around dreamland, particularly in side one’s opening three songs: the chanted spiritual invocations of ‘Peace Go With You, Brother (As-Salaam-Alaikum)’, ‘Rivers’ and the very romantic portrait of nostalgia itself that is ‘A Very Precious Time’. The brief ‘Back Home’ picks up the pace with a pronounced, sugar-coated 70s rhythm, replete with upbeat flute solos from Jackson. It’s almost too sickly sweet alongside the gentle majesty of the preceding three songs, and the lyrical content, concerning the simple joys and caressing hope from domestic familial bliss, are all delivered with none of Scott-Heron’s usual irony. "And don’t you know that makes me think it’s working out fine/ When I get back to see my people." It remains, however, mostly in-line with the poet’s usual cynicism, as the only glimmers of hope during Winter In America lie solely in the past. Whether dreaming back up those rivers to Africa, pining for the innocence of youth via ‘Song For Bobby Smith’ or reminiscing over that ‘Very Precious Time’ of first love ("first touch of spring", as Gil puts it), the good times are well and truly in the past. Summer’s over, and it’s winter in America.

Side two opens with a slice of outright street funk, ‘The Bottle’, which would in fact go on to considerable cult success, charting at number 15 on the American R&B singles charts and ultimately getting repeatedly sampled. It’s the most rhythmic offering on the record, making full use of the bass and drums from Scott-Heron’s fellow Lincoln University students Danny Bowens and Bob Adams respectively. The restless bass lunges all around ‘The Bottle’s irresistible groove, while Jackson goes tribal on the flute throughout. Perhaps less upbeat is the lyrical content, dealing with the grim reality of obsessive alcoholism, told via a series of vignettes connected only by alcohol. A young boy running scared from his drunken violent dad; the depressed lover of a prisoner who’s turned to drink; and (seemingly) an abortion doctor drinking away his shame:

"He was a doctor helpin’ young girls along

If they wasn’t too far gone in her problems

But defenders of the dollar eagle said,

‘What you doin’, man, ain’t legal’

Now he’s in the bottle"

The inspiration for the song came from a group of alcoholics who would congregate in front of a liquor store behind Scott-Heron and Jackson’s house just outside Washington DC in Virginia every morning. "I went out and met those folks," writes Scott-Heron. "I found out that none of them had hoped to become alcoholics when they grew up. Things had arrived along the way and turned them in that direction. I discovered one of them was an ex-physician who’d been busted for performing abortions on young girls."

The poet had been spewing gritty street realism even since, before the likes Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On brought it to FM radio, but oddly ‘The Bottle’ masquerades as a celebration rather than a lament (as on most of Winter). It sure must have led to some inadvertently ironic drunk dances in its time.

‘H²Ogate Blues’ was initially not even going to be included on the album, and perhaps with good reason. It’s definitely in stark contrast to the rest of the album, with no Fender Rhodes, and what sounds like Scott-Heron, Jackson and the guys actually having fun. They simulated a live atmosphere by playing their single take of the largely ad-libbed poem with a blues backing, back into the studio with the studio mic on, capturing some off the cuff comments, giggles, applause and general tinkering from the band and crew. The track opens with an improvised stream-of-consciousness from Scott-Heron on there being some 3,000 shades of "the blues", which morphs into a wordy satire on President Nixon and Watergate, and an outright critical state of the nation address:

"America!

The international Jekyll and Hyde

The land of a thousand disguises

Sneaks up on you but rarely surprises"

It’s a bristling eight-minute outpouring, as Gil Scott-Heron seemingly releases a blowout of discontent at the winter going on in American politics. He names those responsible for the way things are ("Frank Rizzo, the high school graduate mayor of Philadelphia, whose ignorance is surpassed only by those who voted for him"), wields powerful damming allusions ("It seems that Macbeth, and not his lady, went mad"), and fuels his crowd to yell out in agreement:

"How much more evidence do the citizens need

That the election was sabotaged by trickery and greed?

And, if this is so, and who we got didn’t win

Let’s do the whole goddamn election over again!"

The poem was initially going to be left out – presumably as it sticks out like a sore thumb amongst the dreamy, faraway nostalgia and lamentations elsewhere on the record – but drummer Bob Adams insisted. They’d been using the monologue to open concerts, which were all within range of DC enough for folks to know what Watergate was and was not, but Gil Scott-Heron’s concern was that "nobody outside DC seemed to know what the hell [he] was talking about". Adams convinced him it didn’t matter, and that the piece was funny as hell regardless. In hindsight, it’s also an invaluable education and worthwhile as a piece of almost journalistic reportage from a turbulent time in DC too, although it’s questionable how much progress has been made when his concerns are with press intimidation, soaring prices and sickeningly imbalanced wealth distribution. Whatever it means, the ‘H²Ogate Blues’ completes the album, adding a necessary jolt of energy, laughter and anger. Without it, the record could perhaps seem too hopeless, and too nostalgic. As the man himself said, "It provided a perfect landing."

Despite its raw power, and significant ability to stun and shake forty years on, the legacy of Winter In America doesn’t go beyond cult status; it remains somewhat of a footnote even among Gil Scott-Heron fans, too in love with his spoken word and cries for revolution to pay this collaborative mood piece, in a seemingly more resigned mode, much mind. The duo would sign on to the much larger Arista label shortly thereafter, retaining the rhythm section of Bowens and Adams, and expanding their band (rather painfully dubbed the ‘Midnight Band’) to a ten-piece jazz-pop collective. While Winter In America gave them a simmering notoriety amongst the right people, it was perhaps the inflated marketing budget from Arista that boosted the Midnight Band’s album The First Minute Of A New Day, released in January 1975, into each of the American jazz, black and pop albums charts, and the group went on to play some huge gigs, including nights at Madison Square Garden. First Minute has nothing on its forebear, and its two finest moments are both directly descended from Winter In America: ‘Pardon Our Analysis (We Beg Your Pardon)’ (the spoken word sequel to ‘H²Ogate Blues’, discussing Nixon’s Presidential pardon by Ford) and the song actually called ‘Winter In America’. Future Scott-Heron and Jackson records like Secrets and 1980 would vaguely veer off to explore disco and futurist dance music tropes with increasingly tacky and saccharine results (the latter in particular saw them adopt a pretty hilarious space disco vibe; check out the groovy artwork!), but generally the pair never wavered very far from the shimmering keys, entrancing jazz chords and afrocentric wisdom of Winter In America.

Its allure is all down to the strangely universal truths the album serendipitously tripped over. And its message is still as true. The cold hard fact is, a change isn’t just gonna come; it has to come and we have to bring it. If we don’t, then winter will never pass.

"Time is right up on us now brother

Don’t make no sense for us to be arguing now

All of your children and all of my children are gonna have pay for our mistakes someday"

(from ‘Peace Go with You Brother’)