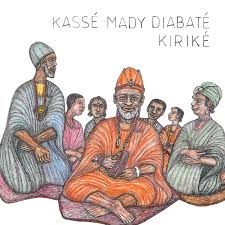

Highly regarded in Mali as "the man with a voice of velvet" and one of the north west African country’s most well-known singers since the early 1970s, Kassé Mady Diabaté has been involved in many ground-breaking releases alongside some of Mali’s best known musicians over the years. And yet you have to go back to 2003 for his last full length release, Kassi Kassé. In which case, the arrival of Kiriké signals a welcome return. Like fellow countrymen kora master Toumani Diabaté and ngoni star Bassekou Kouyaté, Kassé Mady comes from a long line of griot musicians – passing down folklore tales dating back to the Manding Empire.

Kassé Mady has previously been involved in numerous projects with Toumani, including the landmark Mali-Cuban fusion of Afrocubism with members of the Buena Vista Social Club in 2010 and Taj Mahal’s 1999 LP Kulanjan. His latest release sees him team up with kora player Ballaké Sissoko on two songs (whose 1999 collaboration album with Toumani, New Ancient Strings, was another breakthrough album for traditional Malian music – following the album of kora duets by the pair’s fathers, Ancient Strings). The rest of the group includes ngoni player Badjé Tounkara and Lansiné Kouyaté (whose mother was the great griotte singer Siramori Diabaté – and Kassé Mady’s aunt) on balafon, with producer Vincent Segal also providing cello.

Kiriké ("in the saddle") is the third collaboration by Sissoko and French cellist Segal for the No Format label, following previous albums Chamber Music (2009) and At Peace (2012). The all-star "royal" cast they have put together for this release features some of Mali’s finest griot musicians to showcase the majestic, deeply soulful tones of Kassé Mady’s rich baritone voice, in which he sings in Mandinka and Bambara, the dominant language of southern Mali. The group of master craftsmen, whose hands have inherited centuries of precision, come together as an acoustic ensemble to present the music of Mali in timeless fashion, from the kora of the Casamance region, the balafon traditionally associated with the central region and the ngoni from the northern deserts of Mali. Far from being an alien addition, Segal’s cello adds a graceful touch to the hypnotic winding melodies all underpinned by Kassé Mady’s voice, as his stories unfold.

From the age of seven Kassé Mady was trained to follow in the footsteps of his grandfather, known as ‘The Great Griot’. Now aged 65, he has been involved in many of the key moments in Malian music of recent times. In 1970 he became lead singer of the Orchestre Régional Super Mandé de Kangaba, and later he joined a group of Malian musicians that had studied in Cuba – Las Maravillas de Mali, who performed interpretations of Cuban classics (prior to the Afrocubism project). From the late 1980s Kassé Mady spent a decade in Paris, recording the Fode and Kéla Tradition albums before returning to Mali where he collaborated with flamenco group Ketama and Toumani Diabaté on the Songhai 2 album.

The clean polyrhythmic arrangements on Kiriké allow Kassé Mady’s voice to come to the forefront, as he tells the stories that have served to remind people of the Mandé culture the songs document, with themes of nature, life, people, moral messages and cautionary tales that still hold true. Figures of the past are remembered as their tales and characteristics are likened to those around today. On ‘Ko Kuma Magni (What People Say)’, the lyrical flow builds from a near whispered rasp, and builds into full voice, the words telling of the additional role the griot can take on as a marriage counsellor of sorts, conversationally warning against taking notice of rumours and idle talk.

One of the standout tracks, ‘Sadjo,’ relies on a simple, yet strangely haunting melody played on the xylophone-like balafon, the recording picking up an echoey buzz, allowing Kassé Mady’s powerful voice space to tell the story of a mother hippopotamus who spent months searching the Niger River for her child that had been killed by a hunter. Villagers in the area came to know the hippo and found they could relate to her devotion having realised what had happened. Kassé Mady adds: "You cannot call on a griot to ask for help about your fate," and calls for God to provide his fellow musicians with good health.

One of the loosest arrangements comes on ‘Douba Diabira (Family Benedictions)’ with stomping percussive backing in what feels more improvised throughout the repetitive phrases, the musicians running free scales around the structure – with Kassé Mady assuring the listener that benedictions will be observed by the higher authority, but it gets wild towards the end as a way of demonstrating what happens when others do not take this message seriously, with the repeated line, "Oh why is that man over there making fun of me?"

Sissoko appears as the sole musician on album closer ‘Hera (Living In Peace)’, for a duet with Kassé Mady, and his sublime playing demonstrates how much possibility can be offered by the 21-string harp like kora, as dazzling solo runs are pinned down by bass lines and other melodies, sounding like a mini-orchestra in itself. Kassé Mady draws comparisons with Sissoko’s work to the generosity of goldminers in the past, as through their work they protect community values. A voice, presumably Sissoko’s, appears to agree in acknowledgement, both men, collaborating in the ancient art passed down to them over hundreds of years.

Reflecting on the examples of previous griots and their successors, including himself, Kassé Mady Diabaté promotes peace as he sings, "You are listening to the griot from Kela… Living in peace began with the Mandé community where nobody should make false accusations against his neighbours." The enchanting music on Kiriké keeps alive the sacred word of the praise singer and captures one of Mali’s finest voices at his best.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/16749-kass-mady-diabat-kirik-review” data-width="550">