Poet and novelist Jeremy Reed’s long-term friendship with John Balance of Coil is documented – or perhaps more accurately reflected and mused upon – in Altered Balance, a book which is framed around and pivots on the fulcrum of Balance’s death on 13 November 2004. Balance died at the age of 42 from a fall at the home he shared with former long-term life and then-current musical partner in Coil, the late Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson (also of Throbbing Gristle infamy). Divided into poetry and prose reminiscences of Reed and Balance’s relationship and accompanied by Karolina Ubaniak’s elegiac photographs alongside facsimile reproductions of postcards and letters from Balance to Reed, Altered Balance – the title can only be meant for multiple readings – is neither exactly a conventional memoir nor a biography.

While Coil always had cult status even at their peak of popularity, what’s certainly not true is Balance’s assertion, which Reed reports here, that “ten years after you’re dead you’ll be forgotten”. Instead, Coil have entered into a legendary afterlife where barely a review of anything musical which is at once British, weird and potentially a little bit paganist in outlook is not compared in some way or another with the late arch-esoteric electronicists. A true indicator of their lasting legacy if ever there was one. Coil-like and Coilish have become shorthand for electronica with a hefty dose of the unknown, of the unheimlich rippling beyond the doors of perception, of wyrd music which confronts the unconscious and the magickal (self-consciously obscure spellings were a feature of Coil’s look and feel too, as well as in the wider occultist milieu in which they floated), of the outrageously lysergic and the downright weird.

Rather than compressing all the moments of one writer’s highly personal memories into the definitive history of a man who inspires intense devotion from Coil fans to this day, Reed instead provides a flavour of their friendship in a series of anecdotes which reveal much about Balance’s personality and the difficulties not only of being a manic-depressive, born-again pagan experimental cult figure, but of having to live with or be friends with one. Vignettes which slide fluidly though the free-verse poetry recur in the prose passages, expanding on memories which are hinted at, glossed in four-line stanzas which reverberate almost painfully at times with Reed’s still-resonating grief at the death of his friend. For someone who has been a fan of Coil since hearing the first starkly reverberant notes of their funereally-slow cover of Soft Cell’s version of ‘Tainted Love’ (it was immediately obvious that Coil were not thinking of the Gloria Jones original when they made this song their own, just as Marc Almond and Dave Ball did in 1981) a quarter of a century ago, reading the poetry in particular is an emotional experience. It’s strange and affecting to be drawn – allowed, even – into the quotidian details of friendship which reveal much about the multiple public faces of the man who was sometimes styled Jhonn or Jhon Balance but who was known to those close to him as Geoff or Geff Rushton.

Reed muses on and memorialises Balance’s intense relationship with Christopherson; their domestic partnership and its ups and downs are hinted at, though never intrusively or salaciously. Balance’s obsessions with collecting rare occult books and of documenting and archiving the minutiae of every Coil song, recording and related objects paint a picture of a man who was also prone to checking out the sale values achieved by his own rarities in eBay auctions in order to cheer himself up from the after-effects of an alarming daily intake of alcohol – which often included lethal-sounding vodka and Merlot cocktails. Balance’s obsessions, well-known to fans and often obvious from Coil’s music, spring to life from the page: Crowley, gay sex, Marc Almond; and a reference to an unsurprising belief on Balance’s part that if Ian Curtis had not died, then the Joy Division singer would have been an ideal collaborator.

This seems to have been a constant thread from a band who were legendary for the delays which plagued them in a plethora of long-announced, often never to appear, albums or musical guests (imagine if Bonnie “Prince” Billy had sung with Coil). Many never materialised, whether teased and hinted at or explicitly advertised, and others only manifested after Coil was long gone in the shape of posthumous albums, semi-bootleg LPs of Nine Inch Nails remixes and the eagerly-shared demos which periodically appear online. Reed’s memories provide an insight into why so many things that Coil could, should or might have accomplished never came to pass – Balance’s genius, as reported here, was one which trod a fine line, his automatic creativity unleashed and often unhinged in a hail of stimulants both chemical, alcoholic, physiological and psychological. It’s not in the least surprising that Reed describes witnessing Balance reap a whirlwind of upheavals; perhaps these are the sort of episodes which are only to be expected in an alcohol-guzzling self-made shaman who saw Crowlean visions in the park behind his house one moment and then tried to offset his demons by baking industrial quantities of comfort food the next (it’s intriguing and slightly bizarre to learn that Balance pondered the publication of a Coil recipe book, complete with hallucinogen-laced dishes containing ingredients such as peacock eggs, green tea or opium).

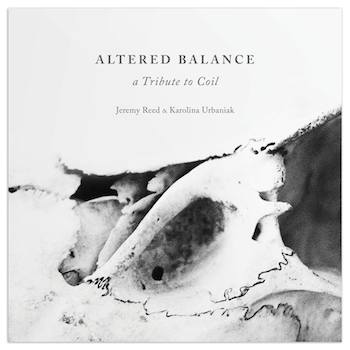

Karolina Urbaniak has selected her photographs to illustrate Reed’s reflections sympathetically and gently, with a series of monochrome images from places important to Balance in both life and death – the leafily suburban and at once quintessentially English houses (with a hint of Gothic) which he and Christopherson shared in Chiswick, west London and in Weston-super-Mare; the spare tree-lined landscape of the rural Woodland Trust plantation where he was laid to rest; of the stark Cumbrian landscape. Also included are scans of the fascinating hand-scrawled postcards despatched to Reed from Coil tour destinations, in which Balance regales him with his adventures and reflections on subjects as diverse as cruising, flower gardens, the architecture of St Petersburg and notes from the Russian fans’ perceptions of Coil’s live performances.

It is an intensely personal portrait of the troubled creativity which gnawed at the existential being of an artist who pushed himself and his works to the limit, franticly worrying at ideas, though not always with the discipline to carry them through. Could Altered Balance be longer? It probably could, and perhaps might have included more about the music, and about the context of Coil outside Balance’s private life. But ultimately, that’s probably someone else’s task; and there is certainly space for someone not so deeply entwined with Balance’s larger than life – and death – personality to do so. Instead, as the subtitle says, this is a very personal and heartfelt tribute to the man who essentially was Coil, even taking into account the vital contributions of Sleazy himself and many other key band members over the years. As such, it’s at once fascinating for the fan and frequently emotionally draining as an insight into the self-destruction that, often almost stereotypically so, drove the delirious dreams of a profoundly gifted and still much-missed artist.

Altered Balance – a Tribute to Coil is published by Infinity Land Press