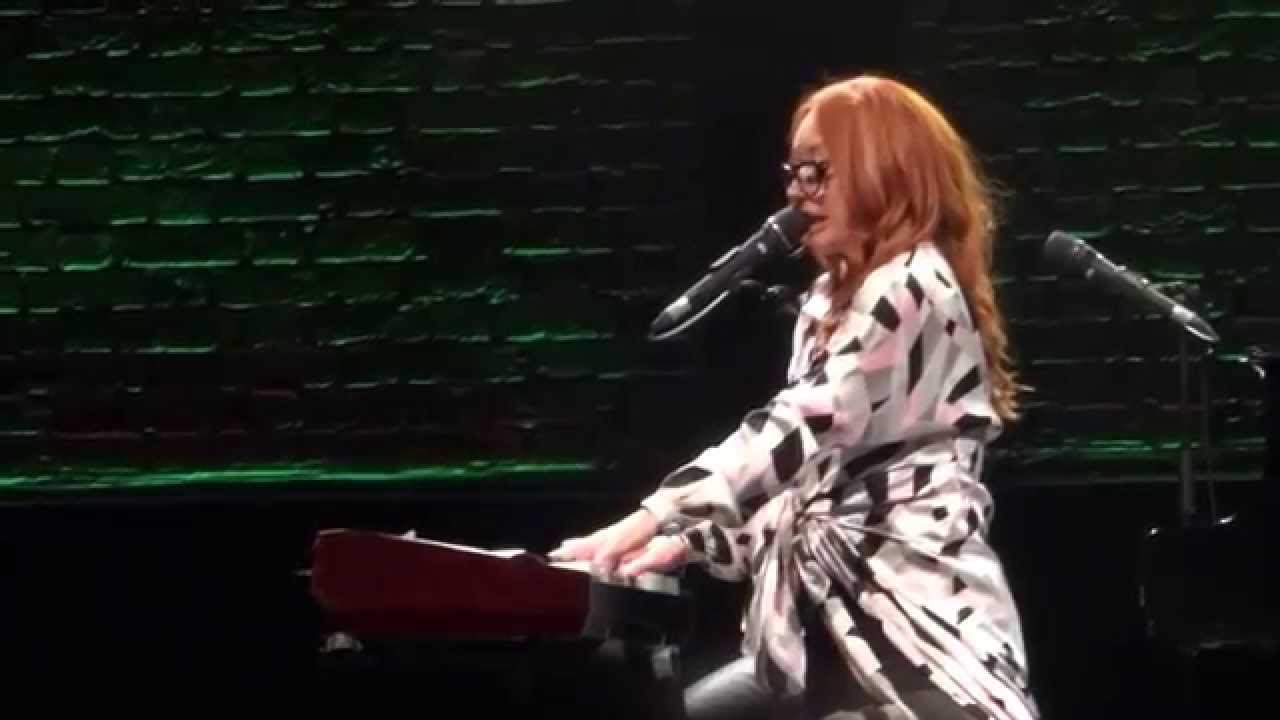

Tori Amos has been touring a lot this year and doing something a number of artists have been doing in recent years – Bruce Springsteen, Taylor Swift and the Arcade Fire come to mind – where they’ve been performing a cover song associated with the city or country they’re performing at any given time. It’s a nice way to break things up and given how utterly pointless the idea of total genre purity continues to be, it can give the artist a chance to showcase something outside the usual expectations of an audience, even if the results can be better in spirit than execution.

So at her Cleveland stop this past summer, she covered a song from the debut album of a performer who had first made his name there in the 1980s, though he was from one state over in Pennsylvania. Said performer had appeared with backing vocals on her own second album Under The Pink and she’s covered ‘Hurt’ live in the past, so it wasn’t totally a surprise. Yet she had never done this song before to anyone’s knowledge, and the result, at 3:46 in in this particular clip, was harrowing and a half:

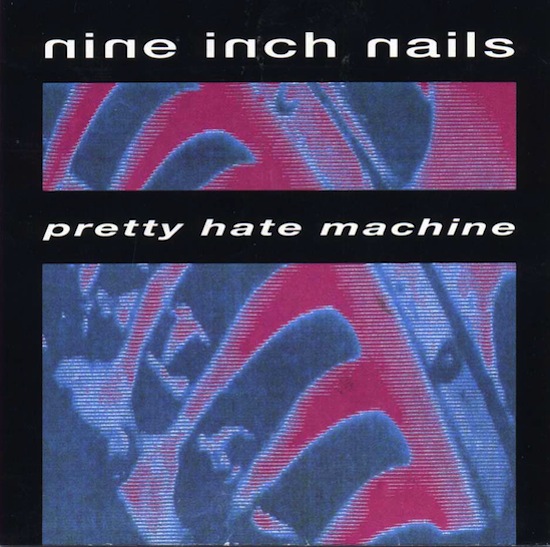

‘Something I Can Never Have’ exists as the poison ballad of sorts at the heart of Nine Inch Nails’s debut Pretty Hate Machine. It is a song that made more than a few friends of mine who similarly got into the album soon after its release confess to me it brought them to tears. It is a bit of tangled desperation and sorrow and anger, utterly self-centered and yet all the more of a pound in the head and the heart as a result. More than anything it might have been the song that made a few of us guess Trent Reznor was in it for the long haul, though I can’t say anybody would have even guessed how long that would turn out to be in the end. Looking back twenty five years, before even bigger albums, Oscars and Grammys and number one debuts and Coil remixes and Lindsey Buckingham guest appearances, and trying to remember exactly what one thought or might have projected forward is a bit of a mug’s game in the end. But the proof really was in the pudding, from the get-go.

Talking about Pretty Hate Machine to any extent means I should start by directing you to Daphne Carr’s book on the album from the 33 ⅓ series, and in fact just stop here and go read that anyway if you haven’t yet. I’ll wait. It delves into things I only half knew or heard about, his upbringing, where he’s from in those Ohio/Pennsylvania borderlands, his being shaped by classic rock and then synth-pop and industrial’s interpretations in those areas as well as from afar, whether afar was London or Chicago or somewhere else instead. In a DVD documentary that came out a few years ago, I appeared along with a slew of others as various critical talking heads, and in discussing Pretty Hate Machine I said something which was equally seen from the get-go: it was Depeche Mode meets Ministry, right down the middle, and specifically the version of Ministry that Al Jourgensen had reworked by the late eighties, a sprawling and overdriven metal-riff explosion. That’s the simple take and that’s how nearly every one of us heard the album if we did hear it soon after release. Oh right this is on Wax Trax! … oh wait it’s on TVT? … sure looks like something on Wax Trax! … sure SOUNDS like something on Wax Trax! …

None of which is to denigrate the album. If anything it’s one of those perfectly formed debuts, honed by Reznor’s previous woodshedding with friend/fellow musician Chris Vrenna, sympathetic producers and engineers (not everyone got to have John Fryer, Flood, Keith LeBlanc and Adrian Sherwood on their formal bow), and a clear monomaniacal vision in the best sense, with Reznor playing everything on it aside from a guitar part by future touring guitarist Richard Patrick. It’s precocious, for lack of a better word, even if Reznor was 24 and not, say, 14. Or 20, which is when the other key role model for what Reznor was up to recorded his own debut release. There’s a reason why Prince was thanked in the liner notes as an inspiration.

And it’s not just because of being a putative role model in studio, one of many. Like Ministry, even though they slathered things in a lot of feedback and grime at this stage of the eighties, like Depeche Mode, who generally preferred a cleaner clatter and stomp, and definitely like Prince at his absolutely focused best, Reznor never, ever ignored a hook that got in and dug deep. Further, he used the tools to hand, and if Pretty Hate Machine is the work of someone assembling all the pieces together and nodding to all the role models that could exist then – I can also hear Gary Numan, Skinny Puppy, Kraftwerk, Public Enemy, lots more besides – it’s all tied up with the kind of tech and especially the kind of electronic beats, punching, pummelling, pulsing, that one could want. You can almost hear him at once trying to move beyond what they have to offer but still just a bit constrained by formalism at this point, just a hair. The chopped up mayhem of Broken showed what happened when he did push a little further but that was still three years and a lot of frustration to come.

If it was all hook in rhythm, then we might only know of Reznor as a producer and songwriter; if he had decided to go that route, he might not necessarily have been a natural rival to Max Martin at this point but that could have happened more than you might think. But he knew his melodies well enough to know how to sing them well too – and if it’s the spiteful performance of a frustrated young man and audibly so at plenty of points, well, again, twenty four years old, and I remember that equivalent time for me well enough, though when I first heard Pretty Hate Machine that was still some years off in my own timeline. Sure, it may be the frustration of emotions rather than, say, societal and structural imbalance, however much ‘Head Like A Hole’ nods to that, but some things are a touch more immediate at that age. Wedding that feeling throughout the album to singalong hooks and great rhythms was the trick, not necessarily a new one but he made the package deeply attractive. They weren’t love songs but they weren’t always hate songs either per se – they were just really, really angry and you could sing them, loudly and angrily in turn.

Sometimes you have to hear the moments in between his lyrics, like the skeletal breakdown after the first chorus and before the second verse on ‘That’s What I Get’, one of many points that suddenly stand out on a relisten for me. (The break’s a beauty as well, one of the more overtly Depeche moments yet still a little more stressed out and churning.) Sometimes that one-word-parody of his vocal approach a friend of mine identified way back when – a pinched, strained "YEWWWWWW!" – can apply. But there were three singles from the album for a reason in the end, each of them tightly wound and to the point, and nearly everything else on the album wasn’t far behind. For example, ‘Ringfinger’ is practically chirpy in the end, even with the Jane’s Addiction sample and the bit about severed fingers; the arrangement is almost debut album Depeche itself, though the ending gets harsher and more engagingly funked out at the same time.

Because the album is such a fully formed debut, it has almost been inescapable for Reznor. The Downward Spiral may have been the total breakout, The Fragile the fractured experiment, Year Zero the concept album/project in toto and so forth, but it all seems to come back to Pretty Hate Machine as that first flashpoint. Even if ‘Down In It’, the actual first single by NIN – the first Halo, to quote the catalog number scheme that has marked every key Reznor release since, his own personal Factory Records life-as-art-as-list move – didn’t end up casting as long a shadow as ‘Head Like A Hole’, it’s a crisp debut. Sherwood’s production shows through on here, the artificial caverns of sound that On-U made its stock in trade, but Reznor’s demi-spoken word/sort-of hip hop flow, the kind of thing a lot of artists ended up doing the following decade, adds a kind of purring intensity all its own. When he suddenly punches up with "I was UP ABOVE IT!" followed by a double echo of what could be a crowd sample or just a smashing noise, he puts his stamp on things much more clearly than before, the song’s easy going lope just a little destabilized by the star power in front.

The final single, ‘Sin’, is more of a naughty-by-numbers move, hinting at fistfucking, transgressions, the kind of thing that really underlines his nods to Depeche Mode and Martin Gore’s own obsession with ruination spelled out more concretely. It’d be wrong not to acknowledge the shadow of Nivek Ogre more fully at this point, though – if there’s a lot of screeching intensity from Al Jourgensen’s work, in Ministry and in other projects alike, that translates through Pretty Hate Machine, there’s also Ogre’s own darkly glamourous star power at work. That may seem counterintuitive given Skinny Puppy’s increasing focus on societal and environmental degradation and destruction, the Grand Guignol they evoked on stage usually leaving Ogre and most everything around him covered in fake blood while images of brutal terror played out behind him. But that compelling theater was as much key to Skinny Puppy’s work as the increasingly fraught arrangements and experiments of their music; the relative focus and easy access of Reznor’s work, more directed at personal angst first over the larger political possibilities, made his own equivalent stage melodrama an easier pill to swallow – not that he wouldn’t find his own way ramp things up with later videos like ‘Happiness In Slavery’.

Other album cuts lingered long in Reznor’s universe, directly or by example. ‘Terrible Lie’ remained an anchor point for his stage shows through the mid-1990s, its cold, slow descending synth orchestrations a glowering crush that sounded like it was taking out Reznor no matter how hard or loud he screamed the chorus. The pinpoint precise cuts between percussive punches, protoglitch feedback and a snarling chorus guitar part during ‘Sanctified’, meanwhile, gave a sense of how carefully he wanted something to have an exact, maniacally focused impact upon listening, for the first time or for the fiftieth. ‘Kinda I Want To’ and ‘The Only Time’, speaking personally, settle more into time-killing perhaps, but as more extensions of the aesthetic it’s hard to argue against them, and sometimes it’s all about the moments, like when everything cuts away on ‘The Only Time’ to big drums, one key melody and Reznor’s own singing, reducing it all down as much as possible while still keeping the core of the song going. Again, he never ignores the hook.

And he certainly didn’t on the opening number, the second single and the one that really kicked it in for NIN from that point forward. ‘Head Like A Hole’, to return to it in full, is almost like ‘Blitzkrieg Bop’ on the first Ramones album – it’s so "Oh, okay, here it is, GOT it" perfect, a summary of exactly what being aimed for, hooks, beats, personalized obsessive I/you focus in larger frameworks, guitars, shoutalongs, anger, rhymes, that honestly sometimes the rest of Pretty Hate Machine could be an afterthought. Frontloading any full album can have its risks, frontloading a debut with that? It’s almost a sign of perfect confidence, maybe even overconfidence. But talk about coming out swinging and not stopping, the way the minimal chirp and clatter suddenly takes in bigger and bigger percussive stomps, the little ‘whoop whoop’ snippets and the rising guitar lines, then snap that snaky little bassline riding over it all, so by the time Reznor kicks in with "God money I’ll do anything for you" he’s got you hooked. It’s a stellar example of pop construction and he just ramps it and ramps it to the chorus, rages through it, then eases back away from it into the next verse. Clever bastard – and within a couple of years thousands of people would be roaring along with it night after night when he was on the first Lollapalooza tour.

Yet again, though, ‘Something I Can Never Have’. The joker in the pack in the end, the song where everything else on the album strips away more than once, leaving just a gentle, sad piano part echoing off into the infinite. It’s way less something between Front 242’s ‘Headhunter’ and Nitzer Ebb’s ‘Join In The Chant’ on a dance floor set, more something that was a kissing cousin to This Mortal Coil or something similar on 4AD, drowned in shadow and sorrow, Reznor’s lyric and performance spiked with anger, fraught with anguish. There are huge stomps on the chorus but even they are buried back too, an echoing clatter around an arena while the spotlight is on the guy and the keyboard in the center of it. That one probably ended up on more mixtapes than people are willing to admit, and maybe Tori had it on one of hers for a while. It could explain her choice of it for the performance, maybe there were other reasons. But it was a good choice of a song to cover, from a great album, a statement of purpose that would lead to much more.