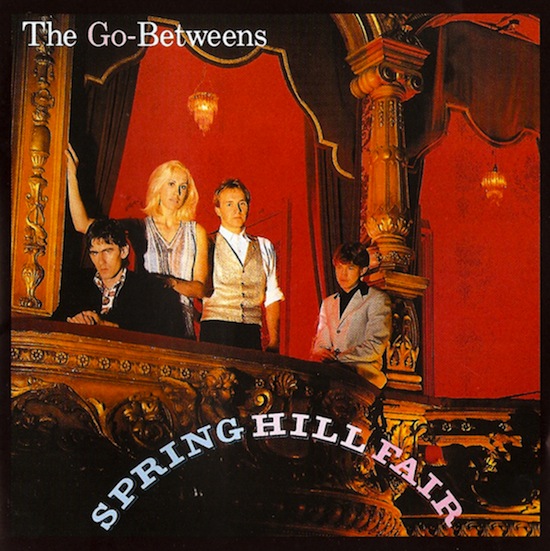

The Go-Betweens became a foursome in 1984. To start with this fact acknowledges the retrospective appreciation with which their career has been cursed, and if appreciation demands financial remuneration, then for years the Brisbane band got none. The band gained and shed members as unexpectedly as they switched labels. For the recording of their third album Spring Hill Fair, Robert Vickers relieved Grant McLennan of bass duties, allowing him to join Robert Forster on guitar (determining who played lead and rhythm was a tricky affair with The Go-Betweens). Decamping to France with some semblance of a budget, the band produced a dense, terse minor masterpiece of literate quasi-pop, with a mechanised thud and Vickers’ root notes at the bottom, flights of whimsy and bemused farewells and awkwardly strung guitars atop, attuned to the spirit of radio pop’s best year but imbued with a romanticism that required sourness for taste and subtlety. John Brand may have produced Spring Hill Fair, but the band showed little interest in the etiolated dregs of the Rough Trade ethos. They were ready. The world thought otherwise.

Relistening to the most acclaimed British, Scottish, and Australian bands of the day should prove educational for those wondering why The Go-Betweens never stood a chance. Robert Forster’s thick, nasal timbre and penchant for talk-singing adduced his commitment to a fey and histrionic strain of English pop with which Morrissey and Ian McCullough triumphed in 1984, but there’s a tentativeness to his approach; he’s like a kid in greasepaint and painted cloak reciting Othello. Discovering in Before Hollywood a songwriting talent that mated a prodigious melodic skill, a demotic correlative in narrative and quasi-lyric poetry of the Betjeman school, and a plainspoken warmth, Grant McLennan was too modest, his troth pledged to small gestures and tense moments recollected in tranquility. And no way in hell were they in Roddy Frame’s league as guitarists, let alone Mark Knopfler’s. There were no suns shining out of behinds, no faiths up against the will in The Go-Betweens work; their name delineated their approach, finding the middle way between pop and film and literature. They’re sober men; they aren’t zany and embrace no contradictions. They were not going to be stars. Occasionally they didn’t mind boring listeners.

I should note that I’m inclined to overrate Spring Hill Fair because it was the first Go-Be’s record I bought. These days I prefer Before Hollywood, whose nervous, jangling bass arabesques and accountings of new feelings still sound like novel answers to the post-punk problem; and Tallulah, bound and gagged in the technology of 1987 but an unabashed pop record, played and written and sung with the intensity of post-punk. But it’s on Spring Hill Fair the band starts to be adventurous about its pilfering: the bass run and nervous picking on ‘Slow Slow Music’, the last vestiges of Byrne-ism (I don’t know where they got the horn section) and Forster’s fascination with Orange Juice; the Buzzcocks rush of ‘You Never Lived’. Finally, like any flawed album by a great band, it includes a farrago called ‘River Of Money’, a spoken word and guitar piece with McLennan going one way and the band the next; it’s the only terrible song in The Go-Betweens canon, further proof that the Velvet Underground’s ‘The Gift’ needed to happen just once.

The single ‘Bachelor Kisses’ still sounds like the centrepiece – my introduction to The Go-Betweens when I bought the Spring Hill Fair in 2000 at the long gone Tower Records in Town Square. The friend and occasional lover to whom I’d passed my Discman couldn’t conceal his impatience. "Sounds like it should play over the soundtrack of an 80s film," he said. It should have. It didn’t. Three carefully picked guitar notes, the high tea kettle hum of a Prophet 5 synth, McLennan making a careful, modest almost entrance. "Hey – wait, oh, please wait, the engine’s running at the gate," he sings, weighing words as if they were just occurring to him. Drummer Lindy Morrison punctuates the end of each bar. Not usually The Go-Between who gets caught out, McLennan has to switch from lovebuzzed to despairing, signalled by a tempo change and his hurling "’Faithful’ is not a bad word" at the beloved. He never defines what exactly is a bachelor kiss–is it what a virgin does or are they kisses given to bachelors? Anna Silver, harmonising with the Prophet over the chorus, adds the missing feminine presence, etherealised beyond scenarios. The middle eight, an interlude of guitar distortions and grunts, doesn’t work: McLennan isn’t up to it, the song’s lilt can’t support it. A redundancy. ‘Bachelor Kiss’ is already a valentine in the guise of a dismissal.

To match the tone and limitations of his voice, Forster contributed songs tinged with sarcasm – the weapon of a man waiting for beloveds to call his bluff; for Forster there is never a nuclear option. A delicate and in bits rather arch breakup lyric floats atop the rippling lead of ‘Part Company’, not to mention another tea kettle whistle Prophet 5. Even better is ‘Draining The Pool For You’, the closest these Australians came to mordant Becker-Fagen storytelling, anchored by a stop-start rhythm that underscores the wisdom of hiring Vickers to lock with Morrison – the old way out is now the new way in, as another song goes. Not to be undone by his partner, Forster bookends the album with his own near-pop gem. "Feel so sure about our love I’ll write a song about us breaking up," he sings, a line that also explains the band’s power and confidence in 1984. Most listeners know the very different single mix, which sounds closer to The Smiths and with determined marketing might have broken top forty England. I prefer the album version, the better to note the McLennan and Vickers’ interplay, the better to appreciate the concluding guitar solo – the longest in The Go-Be’s catalogue, soaring and flapping, burying any notions about Forster (or McLennan)’s prowess.

Because Spring Hill Fair never got an American release until the Beggars Banquet reissues in 1996, the Metal And Shells compilation was many listeners’ first acquaintance with these tunes. Comprising the best of Before Hollywood and Spring Hill Fair, it might be their most consistent stunner; it’s a great way to dip in. But those who came to The Go-Betweens through those exquisite valedictories Oceans Apart and The Friends Of Rachel Worth need to hear these serious young men and woman dismantling what they’d learned and reassembling these parts into shapes that they touchingly thought the world would laud. Spring Hill Fair was lauded, alright, but there was no world. Well. For The Go-Betweens in the 80s, each new record brought fresh hope.