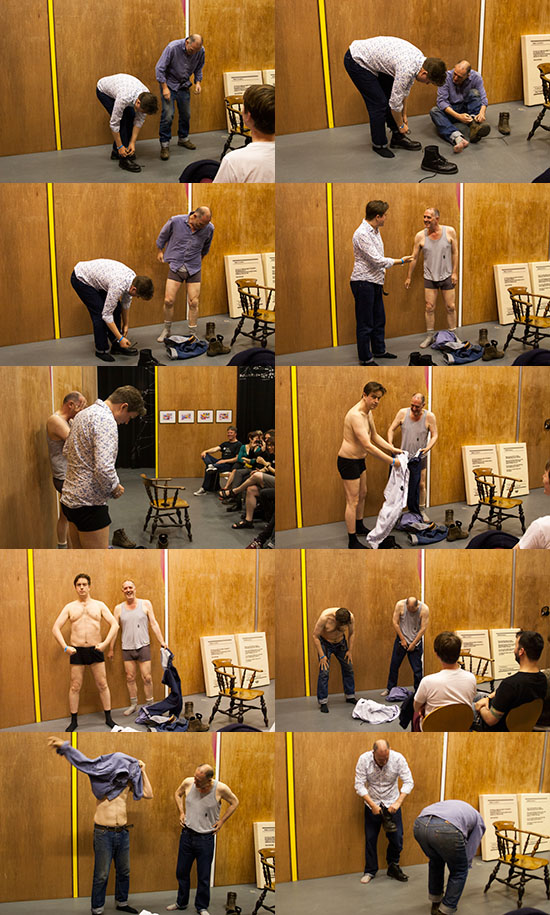

Trigger warning: contains photographs of near naked middle aged men

I’m embarrassed to admit to myself that not only do I not know much about art, but I’m not even sure I know what the word means. I make some notes on a Virgin Trains napkin while en route to see Bill Drummond’s The 25 Paintings exhibition in Birmingham, to try and make sense of how I feel about it.

ONE. Money tends to corrupt. Massive amounts of money tends to corrupt massively. Contemporarily produced gallery art tends to be corrupt and tends to be produced for corrupt reasons.

TWO. People should stop arguing over what constitutes art and simply accept the fact that anything called art by someone who claims to be an artist is art. The real question they should be asking is whether it is good art or not.

THREE. Anything can be art but most things aren’t.

FOUR. I don’t know much about art but I know what I like it to be and do. I like it to be a temporary or semi-permanent zone, object or action that allows a person (artist or appreciator of art) to make sense of an idea, a concept, a feeling or an occurrence.

FIVE. People should question why the language used to discuss art is so obtuse. So-called International Art English is one of the most vexatiously bewildering forms of modern jargon, but why is this? It is easier for popular science authors to explain Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle than it is for popular art critics to explain Martin Creed’s Work No. 227. Is his 2001 Turner Prize winning installation of a light switching on and off really more conceptually complex than the idea that the more you pinpoint the position of one subatomic particle, the more difficult it is to tell how fast it’s moving? It is relatively easy for the layperson with access to the internet, a good library or bookshop to learn about history, maths, literature, geography, politics, music, languages etc, but relatively difficult to learn about art, investment, critical theory, philosophy, marketing, management etc. The first impulse should be to ask: who profits when various subjects are discussed in language that is prohibitively incomprehensible to most, or that repels the right-minded reader by its utter ghastliness?

I’m not sure how much I actually believe the above or what clearly defined proof I have for it, but there are certain points on which I’m not alone.

Last October, Grayson Perry, the flamboyant potter and contemporary artist, gave a series of immensely enjoyable Reith Lectures for BBC Radio 4. During the quartet of amusing and thought provoking monologues, he described in very approachable terms the processes through which critically valued contemporary art has become a modern luxury investment item for the very rich, and how the worth of this art is (in part) validated by the ‘closed shop’ lexicon of International Art English. As a means of illustration he told an anecdote about a former editor of Art Forum magazine who used English as a second language causing the publication to suffer, in the eyes of some, from the "wrong sort of unreadability".

The week after this was broadcast I received a (very well argued and well presented) feature pitch (from an agreeable young writer) slamming Perry’s thesis, stating that art criticism needed to be more complex, not less, which sadly I had to turn down because it was so antithetical to this site’s aim of always communicating in plain English. This writer believed (with great passion and sincerity) in the writings of Theodor Adorno and other critical theorists, and the radical potential he claimed this way of communicating still contained as regards contemporary art. Adorno had helped create a new language in the second half of the 20th century which, as with much modern art itself, was essentially concerned with the nature of the primitive in art while being anything but primitive itself. To my mind the young writer appeared to believe in a double fallacy: that as art has progressed it has intrinsically become so complex that it cannot be explained by ‘normal’ language and that by abandoning ‘normal’ language entirely, art itself can be saved from domination by capitalism.

But the idea that we could design a language so bizarre and difficult to understand that it would completely avoid co-option by capitalists is utopian daydreaming. Those with money are always the first to get with the programme. (It does, however, suggest a bleakly comic alternative future, in which the world’s richest men are advised by crack teams of financial advisors to keep their tax bills as close to zero as possible and a phalanx of brain-fryingly incomprehensible art buyers who laugh at Guattari and Deleuze for being too simplistic.) Ever since the failures of 1968 we’ve been sold this myth of enforced language change as a credible agent of social change, with little in the way of supporting evidence. And as regards art, no matter how complex or simplistic the language in dealer catalogues, it’s going to be a long time before the most valued art isn’t the sort designed to fit in New York loft apartment lifts and through the foyer doors of Swiss banks.

This isn’t some preamble to me declaring all contemporary art that occurs inside ‘The System’ – the sort which is accompanied by a press release that uses the words "synergistic", "alter-modern" and "potentiality" – as degenerate and worthless. I’m sure I’ve been bamboozled by most writing I’ve chanced across on Glenn Brown; Jake and Dinos Chapman are hardly art establishment outsiders championed by the Plain English Movement. (And I would love to own their art but will never be able to afford it.) But for the most part I find it hard to admire any act of creation that’s been made primarily to generate large sums of money, and pretty much despise the linguistic lickspittles who grease the wheels of artistic commerce with their barely comprehensible and ultimately laughable droolings.

Of course there are plenty involved in contemporary art who agree with Grayson Perry’s Reith Lectures, but there are few who are as pathologically and militantly dedicated to demystifying Modern Art Culture and dismantling International Art English as Bill Drummond.

At this point I should let you in on a little secret: I believe Bill Drummond is a better artist than he is a musician. And I have a lot of time for his music. You may disagree with me, but even if you’re a massive fan of the KLF, the JAMMs, the Time Lords, Big In Japan, etc, you’re probably never going to get a better chance to test out this theory for yourself than you will currently in Birmingham. Drummond set up base in Eastside Projects gallery in March and will be there until this coming weekend. (His three month residency in the gallery was kicked off by Drummond sailing into Birmingham along a canal directly under Spaghetti Junction, on a homemade raft, on March 13. This was where he then created the first of his events, which he called ‘400 Bunches Of Daffodils’ – a fairly Ronsealed title for his act of placing flowers in 400 glass jars on a disused canal tow path.)

A few weeks after this started, on April 10, I received a phone call from Maija, his ultra-efficient press person. She wanted to fill me in on his new project and invite me to Birmingham to "observe Bill doing graffiti at midday under the Spaghetti Junction, then going to see his exhibition, The 25 Paintings, at Eastside Projects and then observing his Drummond’s International Grey [his own brand of paint, specifically designed for such public actions] vandalising a billboard at 21.00".

The level of access she was offering, in this age of email questionaires and five minute phoners, was thrilling, but I knew what she was going to say next: "One thing John: you can’t interview him."

He has cut back severely on interviews and only gives a couple per year. One half suspects this is because of a mixture of perverseness, genuine artistic practice and tiredness with answering the same questions about burning a million quid over and over again. However, he is a gent and he wrote the book 100, compiling answers from his final splurge of one hundred interviews before his (partial) retirement from the practice. (When the book came out, I was so enthused by the idea I requested an interview with Drummond to talk about the idea and Maija had to patiently explain to me why that wasn’t going to happen.)

So this means I can watch the graffiti being made, hang out at the gallery, look at The 25 Paintings, watch the defacement of an offensive billboard, but not have to pointlessly ask him if the KLF are ever going to reform or not. Sounds good to me. I’m slightly suspicious that I get asked to do jobs like this not because I’m a good journalist or a sympathetic or useful writer, but because I’ve got next to no short term memory because of decades of enthusiastic ecstasy abuse. (A lot of which occurred with the KLF as the soundtrack, it should be added.) It goes without saying that, whatever Bill says to me on the day, pretty much all of it will have evaporated from my brain by the time I get home and sit down next at a word processor.

East Side Projects Gallery by John Doran

But this all raises another question: if I’m spending the day with him, will I get arrested with him? Coming to music journalism relatively late in life, I was always aware that I was following in the footsteps of some impressive figures in the field, and few more so than the inimitable Quietus scribe and author, Mr David Stubbs. So not only have I found myself returning time and again to many artists that he introduced me to when I was younger, but several of his classic pieces for Melody Maker as well. One article in particular detailed how the KLF were incarcerated after Drummond and partner in Cauty took paintbrushes to a billboard in February 1991. They altered a Sunday Times billboard reading "The Gulf: The coverage, the analysis, the facts" to read, "The KLF…" The arrest was quite a spectacular one and involved three plain clothes officers, two uniformed police constables, a battle wagon and two coppers on horseback. I can only hope. I’ve been drunk with Mark E Smith, had a row with Lou Reed and gotten onto Morrissey’s shit list; getting arrested with Bill Drummond would pretty much be a full house in music journalism bingo.

Although it should be said that attitudes to what constitute civic art seem to have altered somewhat in the subsequent quarter century. We’re no longer a nation who puts its collective foot through the TV screen when it’s announced that a pile of bricks has won the Turner Prize. We’re now a nation who own Rothko mugs and Jackson Pollock brand dish towels. We’re in flux; on our way to being something else; certainly more urbane but maybe less questioning as well. It’s not so long ago that I saw a group of fully grown adults weeping in Hackney as council workmen started painting over a BANKSY doodle. Such was the outpouring of grief that the workmen abandoned their job, meaning the picture of what appears to be Moomins waving from a balcony has been saved for future generations. Hopefully the British Transport Police of the West Midlands share the same open-mindedness and sensitivity to the perpetrators of guerrilla art. I book an open-return to Birmingham just in case though.

The concept of The 25 Paintings project is at once simple but also hard to sum up succinctly. It is essentially an exhibition which represents the culmination of a quarter of a century of work by Bill Drummond as an artist. There are an actual 25 paintings in the exhibition but they are not, as Drummond writes in the (excellent) exhibition catalogue, "the important bit".

As he explains: "The important bit is what I will be doing in and around Birmingham – including Eastside Projects, for those three months. What I will be doing are all ways of working that I have developed at various times over my life.

"The 25 Paintings exist primarily to act as markers, signposts and advertisements for what it is I will be doing in Birmingham for the period I will be there.

"The 25 paintings exist in several forms. All 25 exist as traditional paintings on canvas. They also have a double life as 25 wall paintings on the walls of Port-au-Prince in Haiti. They can also exist as 25 Head Paintings that I paint on my own head from time to time. There are also scale model versions of The 25 Paintings that exist for the market."

And what is it that he will be doing in and around Birmingham? Well, as well as painting graffiti and defacing billboards, he will be taking part in what he terms "direct action" – a phrase loaded with clear meaning – by making beds (as in constructing them out of wood with mallet, plane, saw and chisel, not fashioning the bedding into neat hospital corners), baking cakes, cooking soup, polishing people’s shoes, sweeping streets, getting his hair cut, reading the Bible and, of course, applying paint to canvas, billboard, wall and noggin.

For three months every year for the next twelve years or until he dies, Drummond, who has recently turned sixty, will be repeating the process in eleven other cities. This is, in some respects, a grand summing up of his entire career as an artist.

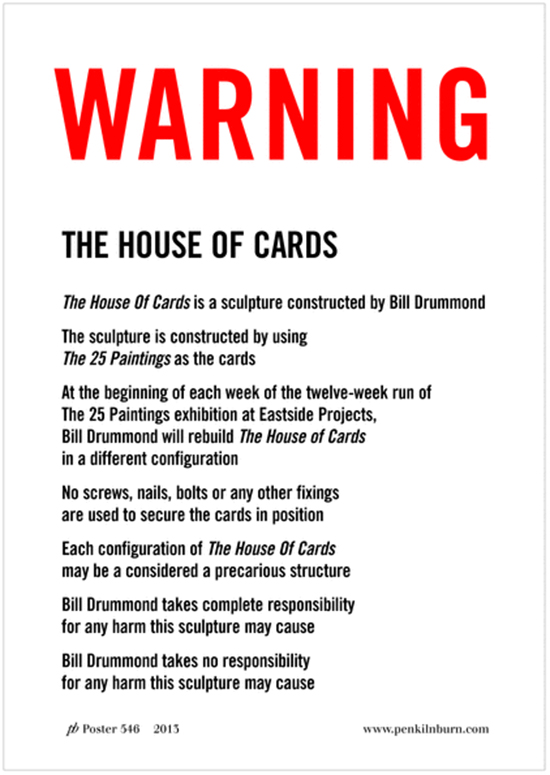

When I get to the gallery, which is in Digbeth, only a stone’s throw away from the Custard Factory where Capsule have been holding their excellent Supersonic Festival for over a decade, Bill is there discussing the day’s events with his friend, the photographer and artist Tracey Moberly. I go for a wander round the gallery while waiting for them to stop having an interminable conversation about paint rollers and cameras. Inside the main gallery space, small versions of the actual 25 paintings hang on one wall, flanked either side by a large map of the UK and an OS map of Birmingham itself, which has been annotated in black pen regarding several of the actions that have already taken place. Taking up the entirety of another large wall are posters detailing previous actions from all around the world. In the centre of the room the actual 25 paintings have been stacked like a house of cards, several storeys high. There is also much evidence of artistic endeavour. There are two partially constructed wood-framed beds, some chairs surrounding some squares of knitted wool; a big drum stands on its side with two beaters propped up next to it; there is an orange traffic cone, and a broom with a high-vis jacket hanging from it.

On another wall, next to some cuttings about the project from the local paper, there is a flat-screen TV which features a jovial and slightly manic looking Drummond explaining, in the loosest possible terms, what he’s doing.

I spent the entire train journey here working out how I was going to get him to tell me stuff without interviewing him, but ended up reconciling myself to the fact I’m just going to be writing a colour piece. This is the point perhaps, that art can and should speak for itself; that institutional art is often protected in a thick webbing of International Art English, not because it deals in concepts that are next to impossible for most of us to understand, but that it generally has a paucity of useful ideas. What better way can there be of letting the art speak for itself than not interviewing him? And of course, if I hang out as a fly on the wall in the gallery, sooner or later someone will come in and start talking to him about this fascinating venture. As long as they’re not some insane KLF fan, I’ll be laughing.

Just as I’m thinking this, a glassy-eyed, middle aged man sits down at the table next to Bill and Tracey and announces, in a very pronounced Wolverhampton accent, "Bill, it’s a pleasure to meet you. I’m very, very, very, very obsessed with the KLF."

If Drummond is annoyed by this, he does an A1 job of hiding it. Even when the guy – who is tired and unemotional – starts suspiciously digging for information on the many KLF white label dubstep and trance remixes that flood the EDM market every year. "They’re obviously done from the masters…" he suggests calmly. "Well, not by me", counters Bill. "But someone must have the masters…" he suggests with a faraway look in his eyes. "The master tapes are in a box under my bed" says Bill, "And believe you me, I’ve been too busy to remix them."

The man is unconvinced and looks unlikely to let the subject drop. "There are hundreds of these white labels. I’ve got most of them here…" He starts calling them up on his phone.

"Don’t play them to me, for God’s sake!" laughs Bill stridently, in a way that conveys both humour and the idea that the man really shouldn’t start broadcasting some Skrillex-style bootleg remix of ‘3AM Eternal’ on his Samsung GS3 to the gallery. The artist may have turned sixty recently but he’s big and well built, exuding a natural air of authority. The man puts his phone away, causing Drummond to add, in a conciliatory manner, "Look, I’m just done with all that. It was a long time ago and I’m doing new stuff now. After all… you wouldn’t want to be still doing what you were doing 25 years ago would you?"

The man doesn’t say anything, clearly unwilling to contradict what his hero has just said.

Bill and Tracey are going to Spaghetti Junction in a van, so Nathan Hansen, a production assistant from the gallery and I take a cab and end up getting there first. We slouch inside a dimly lit underpass out of the drizzle, far beneath the graceful, elevated reinforced concrete loops. A man in a hi-vis security jacket with an Alsatian on a chain eyes us suspiciously as he walks past. "Christ, we look like drug dealers," says Nathan. "There is an easy solution to that," I say. "Drug dealers don’t interview their customers." I get out my dictaphone and ask him some questions.

You’ve managed to cram so much stuff into one gallery space… it’s quite dizzying really, I say.

He nods: "The house of cards was a bit of a nightmare. We weren’t sure if it was going to topple down and then we had to add extensions on to walls just to get his works up there – which should give you some idea of how much material is in that space."

Can you tell me in your own words what 25 Paintings is and what it’s trying to achieve?

He adds: "I’m not going to say that Bill doesn’t like the art world… he just doesn’t like the structure of how some of it works. So he’s got this idea of making art into something that is useful, and can be brought back into the community, or brought back to people. That’s why he’s doing things like baking cakes and sweeping sidewalks and doing things which are not necessarily aimed at art buyers or traditional art lovers."

Bill’s white Ford Transit van eventually pulls up and we unload a couple of large buckets of brilliant white matt emulsion paint, a roller, a bag of brushes and some boards. We walk through a couple of pedestrian tunnels across a large motorway roundabout, across multiple slip road exits, darting through gaps in the fast moving traffic, then along a busy slip road. A police car drives past us, but doesn’t slow down. We hop over crash barriers and down an old, overgrown access path that runs under one of the great flyover loops and is flanked by impressive concrete legs. We hop over another fence and onto a canal tow path. This stretch of canal is completely blocked in by walls and a concrete lid, protecting it from the noise of the thunderous traffic above, although daylight can be seen a few hundred yards away in either direction. We walk along to the spot where everything started on March 13th. There are still 400 glass jars on the tow path, all containing now-past-their-best bunches of daffodils. The wall above this is lit gracefully by daylight streaming through a 12" by 12" grate in the concrete ceiling. It’s like looking at the wall of a gallery in a post apocalyptic industrial landscape but, it should be said, it does genuinely have the aspect of a gallery wall.

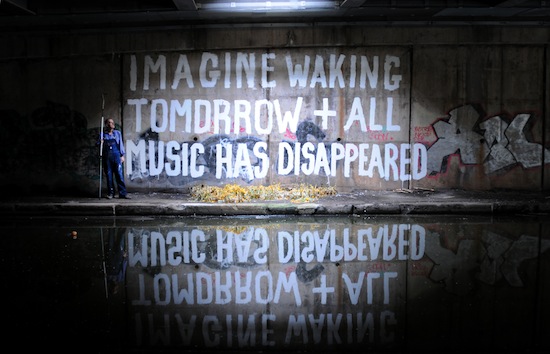

Bill mutters to himself, looking at the expanse of dirty concrete wall in front of him, as Tracey sets up her camera on the other side of the canal. When he starts he makes light work of the task, which is not surprising given how many times he has painted this particular piece. In fact, when the Quietus were based at Hackney Wick I had to walk past an identical message to this every single day on my way to and from home.

It takes him less than fifteen minutes to paint the phrase: "IMAGINE WAKING TOMORROW + ALL MUSIC HAS DISAPPEARED" neatly along two rows on the towpath wall.

The rapidity of the paint job results in little tracers and splashes of white paint all over the green and yellow bed of daffs, like some kind of weird Jackson Pollock tribute.

It looks great, but he has messed up the M of Music. His solution is to get his paint roller, dip it in the canal water and rub it on the muddy towpath floor until it is covered in the dirt of ages. Then he vigorously applies it to the space round the letter. He shouts over, "Tracey, can you read that as an M?" She nods consent and then starts taking pictures – some with him holding the tools of the action in outstretched arms, and some of the graffiti on its own. The efflorescence of paint in the dark canal water eventually sinks out of view, and we pack up and head back for the van.

Back at the gallery we chat – it’s not an interview! – about his idea for painting out a billboard, and he explains his most recent modus operandi for this. He has concocted his own brand of paint especially for the job – Drummond International Grey – and he uses rollers to carry out an inverse act of vandalism. He blanks out the entire billboard in the paint except for the outlines of the word ‘GREY’ which display the colours underneath. But he won’t be carrying out this action today, he hasn’t found a billboard which irks him and offends his moral and aesthetic sensibilities enough. He mentions payday loan companies and chain bookies as examples of what he’s looking for, but says he hasn’t seen any about. He seems preoccupied though – unsurprisingly as it turns out, as he has a family funeral to go to. So I say I’ll head off and come back over on another day to witness a different action.

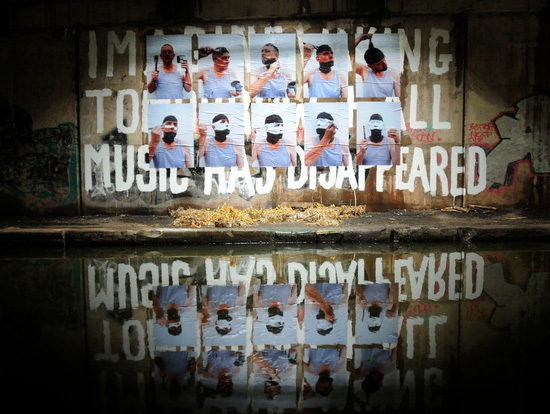

When I come back on May 1st it turns out we’re heading back to exactly the same spot under Spaghetti Junction, but this time to put up fly posters. There are ten A1 sheets of paper showing Bill in different stages of painting his head. He has come up with 25 of these series of head paintings, one to represent each 25 of the paintings or actions. They coincide with the colour schemes of the 25 canvases in the gallery. While we’re walking down to the spot, I tell Bill that I can tell from the photos that when he does this paint gets in his eyes, and that I can tell by the expression on his face when it’s hurt the most.

He suddenly becomes animated: "Oh yeah! I mean, when I wash the paint off and open my eyes, there are often colour paint lines across my eyeballs."

Tracey sets up across the canal again and shouts instructions across to Bill so he can get the sheets of paper square to the wall and floor. He slops wallpaper paste onto the wall with a brush and then places the sheet on top of that, before going over the whole area with more paste. He completes this action in even quicker time. During the procedure I spot not one but two separate herons at either end of the covered section of the canal. They are massive and ominous. One of them looks like it’s struggling to eat a wriggling eel. It’s a relief when we can beat a retreat. The sweet smell of the rotting daffodils builds in waves, each stronger than the last, becoming more and more unpleasant.

Then back at the van he gets changed for his next action, donning a hi-vis jacket and a large brimmed hat and picking up his big stiff broom. This is ‘The Lone Sweeper’ and he will sweep the road clean in a line between Spaghetti Junction and Aston.

He actually admits to me that he’s cheating and only posing for photos today. He’s got cold feet about doing this during the hours of daylight because, as he says, "I’ll get arrested immediately."

It was my theory originally that Bill doesn’t get arrested nowadays, simply because he looks like he should be there, but obviously there are limits to how far this will get you. I tell him I think he’ll be alright – after all, he’s wearing a hi-vis jacket. Surely that will prevent him from having his collar felt. He looks at me like I’m mad and says: "Fashions in hi-vis jackets are seasonal, not to mention annual, and have moved on somewhat from when this was made." As if to prove his point a genuine motorway worker carrying cones walks past looking like something out of TRON. By contrast, Bill looks like an Amish minister who has belatedly discovered nu-rave.

We all shake hands and go our separate ways. It’s been a great experience, watching an artist up close, seeing him interact with members of the public and change his programme at the drop of a hat. However the journalist part of me can’t help but feel cheated. Don’t get me wrong, I understand why a sixty-year-old man with teenage children at home waiting for dinner to be put on the table doesn’t want to spend the night in the cells, but I still have a sneaking suspicion that I’ve not yet seen all that the 25 Paintings project has to offer, and am not entirely convinced that I’ve caught the spirit of it.

The trajectory of 25 Paintings also alters rapidly a few days after my visit. I find out via his column for The Birmingham Post that he didn’t have to wait long for a hoarding with morally and aesthetically irksome properties to come along.

In this column he describes his decision to target a UKIP billboard: "As I strolled along Heath Mill Lane towards Eastside Projects, I was confronted with a billboard that offended me in so many ways…

"Over these past weeks working across Birmingham I have often been asked if what I do is political art. My usual answer is ‘I do not know if it is art, let alone political art.’

"…yesterday morning I walked past that billboard in Heath Mill Lane that was very cynically trying to pander to us at our most vulnerable and negative and not to our better selves.

"I may be in danger of overstating it, but this would have been exactly the same appeal the National Socialist German Workers’ Party would have had in Germany in the years after the First World War, when the German people were feeling at their most beaten and vulnerable.

"This billboard not only offended me morally and aesthetically, it also went against everything that I feel political discourse should be about.

"Thus there was nothing for it, after my train pulled into Moor Street, I picked up my last remaining tins of Drummond’s International Grey and got to work."

It was a shame I didn’t get to witness the action, but good on him, and at least I didn’t get arrested.

With the European Elections then only days away it doesn’t take long for the story to go national, and I get into a mild dudgeon about my own story being non-existent in comparison.

However, I have one more opportunity left to interact with The 25 Paintings. Right at the end of May, I’m heading over to Digbeth for Supersonic, and I decide to drop in on East Side to see if anything is going on with the project. As I walk into the gallery Drummond spots me and shouts, ‘Haircut!’ in an approving manner. Probably simply approving of the fact that I’ve actually had one, rather than the style. Of course, it goes without saying that barbering is one of the 25 actions he has unleashed in Birmingham.

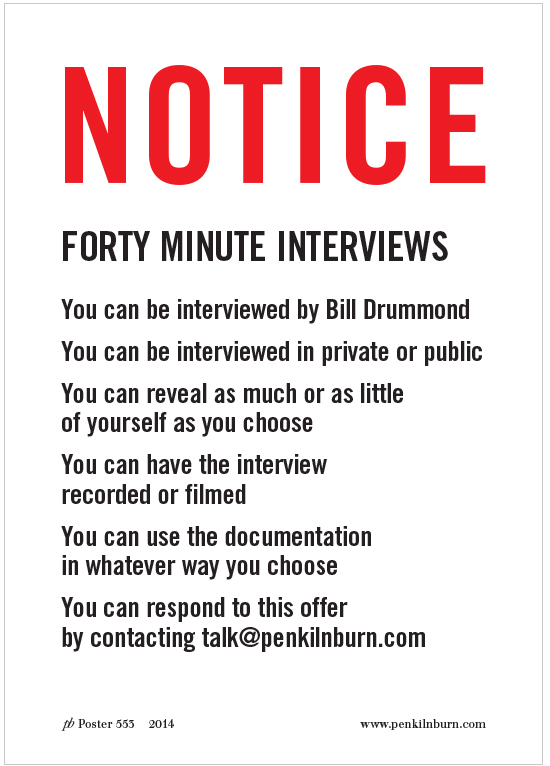

As the project has progressed, it has changed direction several times. He has painted over some of the paintings as the idea has evolved. So now, inside the gallery, one of the paintings hanging on the wall reads ‘TALK’ instead of ‘WALK’. As he has explained, the good folk of Birmingham are fond of a chat, and he has found himself spending more time explaining what he’s doing to interested strangers than he has completing his actions. So now he is in the middle of carrying out 40 interviews with Brummies, each lasting 40 minutes.

He explains to me that he has one of these 40 interviews lined up with a local politician and that I can either wait for him to complete this task or give him a hand. As sad as it sounds, busman’s holiday or not, I love interviewing people and jump at the chance.

Karl Macnaughton is a Green politician serving on Solihull Council. I’ve included a brief excerpt from the interview, simply because, in some ways, this brief chat does a better job of summing up the exhibition than the rest of the feature does, if I’m honest.

Bill Drummond: "How did you know about this?"

Karl Macnaughton: "I read about it in your column in The Birmingham Post. You were going to talk about the flags, but you ended up talking about how everyone in Birmingham talked to you, so you created this little project with them in mind."

BD: "So you’re from Birmingham then?"

KM: "Yeah, kind of straddling the border between Birmingham and Solihull."

[There is a lengthy discussion about the nature of Birmingham as opposed to other UK cities, and some pondering on why the China Towns and gay quarters of cities are nearly always next to one another]

John Doran: "Have you ever been in a situation where you’ve thought, ‘I’m not going to get out of this alive or without serious injury’?"

KM: "The first thing that comes to mind is something ridiculous actually that happened when I was doing a walk from Land’s End to John O’Groats. I got stuck up a tree with a dog at the bottom of it. It was in a place called Leedstown in Cornwall."

BD: "So you hadn’t got very far…"

KM: "No. I was walking down a footpath that actually started looking less like a footpath and more like someone’s very, long and winding driveway as I went down it. Then I saw that there was a kennel in the distance and thought, ‘I don’t like this… I’ll take my rucksack off, just in case I see a dog coming… Shit! Shit! The dog’s coming!’ So I climbed up the tree using my rucksack as a boost, and I was up there for quite a while. About half an hour, working out what to do. I was thinking, ‘Well, the dog looks quite old…’ But in the end I had to phone the local police, but it was all over by the time they got there. The dog’s owner arrived and it turned out that not only was the dog very, very old but it was also blind. Word spread very quickly. I had been on the wrong path, and as I was heading back to the right footpath I passed a woman on a horse who shouted, ‘Are you the guy who got stuck up the tree?’"

[It then transpires Drummond has a friend who did Land’s End to John O’Groats on a penny farthing]

BD: "So you’re a Green politician for Solihull Council…"

KM: "As of last Thursday there are now ten of us, so we’re the official opposition. The Conservatives are the main party."

BD: "Howcome the Green Party are beating the Lib Dems and Labour in your area?"

KM: "Labour, if I’m being really honest about it, have been there for a long time and were quite complacent and not really engaging with the community. We felt the community we wanted to represent needed a bit of love, and so we went along and did what politicians are supposed to do really – we knocked on a lot of doors and talked to people about their concerns. We are interested in helping people wherever we can and empowering them wherever we can. We did that and won."

[Karl talks a very good game about why a vote for Green isn’t a wasted vote, and about his party’s policies. Bill starts wrapping up.]

JD: "I’ve got one last question. Can you tell me what you think about The 25 Paintings and how it’s made you think about art after experiencing it?"

KM: "Art has always confused the hell out of me, if I’m being honest. I’ve been to art exhibitions and thought, ‘I like that. I have no idea why and I have no interest in interpreting it to be honest.’ Or I go to an exhibition and come away with my own little interpretation, which is probably nothing like what the artist envisaged. I think a lot of the problems with art culture is that [traditional ‘art people’] try to out analyse each other… and that drives me insane. This art that you’ve got out here… the reason I know Bill is because the KLF were my favourite band when I was sixteen. But as a result of that I’ve seen some of his art and read some of his books. And I always thought his art was a bit different, because it doesn’t try to prove anything. I would say it is Bill creating a set of circumstances, and then seeing what happens. And I really like that. That’s what I do to a certain extent. I’ve got this thing called the Bee(r) Bus Adventure. This is going to sound insane, but essentially me and my girlfriend take these furry little bees she’s had since she was little on a pub crawl."

BD: "You take bees to the pub?!"

KM: "They’re toy bees. They’re not real bees. You start at the first pub, you have a drink, you go out of the pub, turn left, and keep on going until you reach another pub or see a bus stop. If you get to a bus stop, you get on the bus and stay on it until you see a pub, and then you get off and go for a drink there. And you do this six times. All I did was create those rules. I wrote them down and thought, ‘What will happen if we do this?’ And it’s been great. We’ve met strange people. We’ve been into pubs we never would have been in otherwise, and we’ve explored the city. And it’s not like I consider this art. When I was in school I was in the top class for everything apart from art. I was in the bottom class for art, because I was shit at it. Everyone else was there because they twatted about too much. But that was only really one type of art. I had a strange experience of art until I found out about this kind of art. The kind that wasn’t just paintings…"

After Karl leaves, I notice that the artist has painted a sign in the middle of the gallery that states: "Today Bill Drummond will be launching his career as a cross dresser: 31 May 2014." But I’m not given any chance to ponder what it means. Instead, along with 35 other visitors to the gallery, I’m ushered into a room where he is holding court on the subject of Haiti, and specifically why the 25 paintings don’t just hang in the gallery, but are painted on walls across the city of Port-au-Prince.

He describes a trip to the city in late 2009 to write his piece of graffiti about music disappearing and to organise a performance of his choir, The 17. The former was an odd thing to paint, as the only constant in the city was non-stop music. Or, as Bill puts it, "the only thing that made life in Port-au-Prince tolerable". And the latter involved a hundred youngsters standing round a large city block and shouting, ‘Wayo!’ one after the other until it had passed round the entire group. However, due to an oversight, he hadn’t made a list of who had taken part in the choir, and word spread rapidly, attracting a lot of people down to the portacabin he was in, who then demanded a $3 participation fee. Things started turning ugly and he had to escape over a wall, while things for the kids who did get paid looked decidedly grim. We go out into Digbeth to recreate the vocal action of that particular version of The 17 and the scuffle for money afterwards.

Less than two weeks after his visit to Haiti, while Bill was safely ensconced back in the UK, the earthquake struck and killed 200,000 people – including lots of people who had worked with him on the project. But now there was no music in the city and most of the walls had fallen down. In fact, in one bit of Port-au-Prince, literally every single wall had collapsed, bar one small section: the bit that bore his graffiti. "IMAGINE WAKING ONE DAY + ALL MUSIC HAS DISAPPEARED". He describes how he became a figure of hate among some people, who now believed that he had predicted, or in some cases actually caused, the earthquake.

Haiti doesn’t have billboards. It simply has sign painters who are contracted to paint advertisements on walls. Of course this job, along with much else, has been decimated. It is now easy to see why Drummond pays these sign writers to paint facsimilies of his paintings on local walls.

It’s a great story, well told, with seemingly very little concern for how it makes him look. In fact it’s spun so well that it makes me forget completely about the bizarre sign about cross-dressing that he painted just an hour or so earlier.

He explains that he is far too boring and predictable when it comes to sexuality and that he doesn’t hanker after dressing up in women’s clothing, so he says that he will swap clothes with one of the 36 people in the audience.

He adds: "And there’s a journalist in the audience writing about the exhibition and it just so happens he is exactly the same size as me."

For a brief hopeful second I look around the room for another 6’4" journalist, before resigning myself to my fate. I querulously complain about my journalist’s physique and how I would also have worn a vest if forewarned about the ‘action’. (However, it should be said that Bill’s clearly in better shape than me.) Earlier that morning, I spent some minutes debating whether to wear a floral print shirt or a Slayer T-shirt, and now really regret plumping for the former. We pose for before and after photographs and the merciless camera is trained on me all the way through the public uncloaking.

Bill shouts to the audience: "So, I have a feeling that this journalist felt this morning that he didn’t have his story. Do you think he has his story now?" They roar their assent that I have my story.

All ‘Cross Dressing’ pictures taken by the fearless Katharine Round

I get dressed, say goodbye to him and start heading back to the Supersonic festival. I’m not sure whether what I just took part in was art or just an elaborate way of giving a slightly persistent journalist the brush-off. If I was forced to, I’d describe it as an act of giving a journalist the brush-off raised to an art form. But at that very moment I’m unconcerned with whether any of it was art or not. My head is otherwise engaged, awash with the idea of sailing out of Birmingham on a homemade raft covered in daffodils. It’s fully engaged with the idea of predicting natural disaster with graffiti, of what the world’s largest knitted blanket would actually look like, of taking some bees on a pub crawl. And I think of the joy and inspiration that can be found in knowing what one likes.

To find out about the remaining few days of The 25 Paintings in Birmingham click here

Events on the final day, Saturday 14 June, look like this:

Noon – 2pm

Drummond will be baking scones in the kitchen of Eastside Projects.

2pm – 5pm

Drummond will be serving Birmingham Cream Teas, while the Knit & Natter group sew together all of the squares knitted during their residency in Birmingham.

5pm – 7pm

Eastside Projects will be closed in preparation for the night ahead. And Drummond will be transforming into alter ego Tenzing Scott Brown.

7pm – 10pm

Tenzing Scott Brown will play a DJ set. The set will include all of his collection of forty seven inch singles, played in the order they were released.

Midnight

Drummond will make his ceremonial departure from Birmingham on a raft made from his bed, on the Grand Union Canal underneath Spaghetti Junction